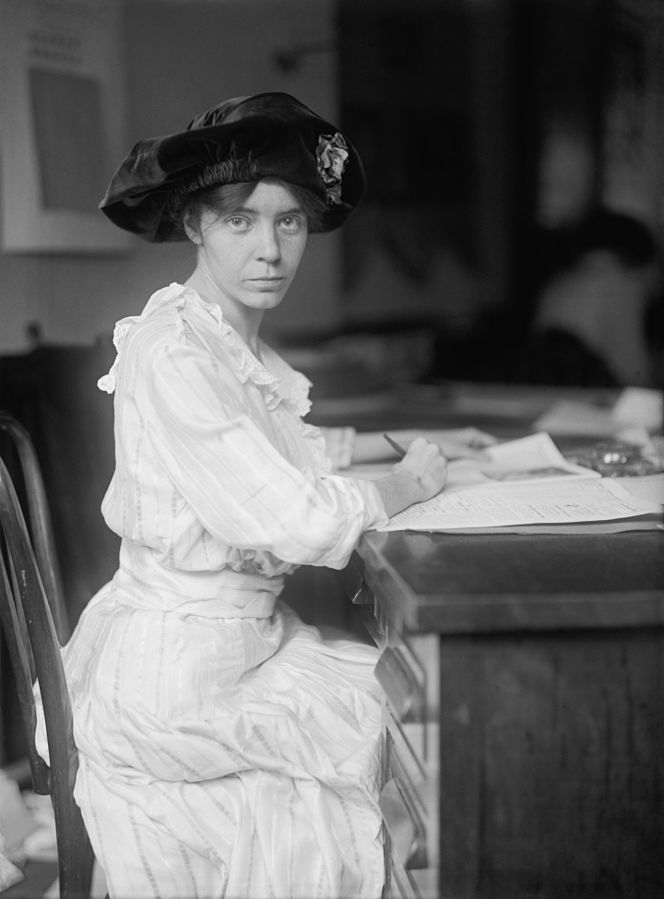

An interview with the famed suffragette, Alice Paul

-

February 1974

Volume25Issue2 -

Summer 2025

Volume70Issue3

American women won the right to vote in 1920 largely through the controversial efforts of a young Quaker named Alice Paul. She was born in Moorestown, New Jersey, on January 11, 1885, seven years after the woman-suffrage amendment was first introduced in Congress. Over the years the so-called Susan B. Anthony amendment had received sporadic attention from the national legislators, but from 1896 until Miss Paul’s dramatic arrival in Washington in 1912 the amendment had never been reported out of committee and was considered moribund. As the Congressional Committee chairman of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Miss Paul greeted incoming President Woodrow Wilson with a spectacular parade down Pennsylvania Avenue. Congress soon began debating the suffrage amendment again. For the next seven years—a tumultuous period of demonstrations, picketing, politicking, street violence, beatings, jailings, and hunger strikes—Miss Paul led a determined band of suffragists in the confrontation tactics she had learned from the militant British feminist Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst. This unrelenting pressure on the Wilson administration finally paid off in 1918, when an embattled President Wilson reversed his position and declared that woman suffrage was an urgently needed “war measure.”

The woman who, despite her modest disclaimers, is accorded major credit for adding the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution is a 1905 graduate of Swarthmore College. She received her master’s degree (1907) and her Ph.D. (1912) from the University of Pennsylvania. Miss Paul combined her graduate studies in 1908 and 1909 at the London School of Economics with volunteer work for the British suffrage movement. Together with another American activist, Lucy Burns, she was jailed several times in England and Scotland and returned to this country in 1910 with a reputation as an energetic and resourceful worker for women’s rights. She promptly enlisted in the American suffrage movement, and opponents and friends alike soon were—and still are—impressed by her unflinching fearlessness. “Alice Paul is tiny and her hair has turned gray,” a sympathetic feminist writer recently observed, “but she is not a sweet little gray-haired lady.”

Miss Paul’s single-minded devotion to The Cause is, of course, legendary in the women’s movement. During the early struggle in the 1920’s for the equal-rights amendment (E.R.A.) now up for ratification, she went back to college and earned three law degrees “because I thought I could be more useful to the campaign if I knew more about the law.” A similar pragmatism continues to govern Miss Paul’s daily activities. She admits to a gracious impatience with interviewers who seem, from her perspective, obsessed with the past. “Why in the world,” she politely but firmly inquires, “would anyone want to know about that?” And she pointedly delayed her conversation with AMERICAN HERITAGE until after the 1972 Presidential election so that she could spend all her time getting the candidates publicly committed to the ratification of E.R.A. President Nixon, she explained, was one of the “charter congressmen” who introduced the equal-rights amendment in 1948 and has remained a “friend” of the movement. But she voted for Senator McGovern “because in this campaign he took the stronger position on E.R.A.”

Today, at eighty-nine, Miss Paul no longer commutes regularly from her hillside home near Ridgefield, Connecticut, to the Washington headquarters of the National Woman’s Party, which she founded in 1916. But her interest and influence in the crusade for women’s rights remain undiminished. “I think that American women are further along than any other women in the world,” she said. “But you can’t have peace in a world in which some women or some men or some nations are at different stages of development. There is so much work to be done.”

How did you first become interested in woman suffrage?

It wasn’t something I had to think about. When the Quakers were founded in England in the 1600’s, one of their principles was and is equality of the sexes. So I never had any other idea. And long before my time the Yearly Meeting in Philadelphia, which I still belong to, formed a committee to work for votes for women. The principle was always there.

Then you had your family’s encouragement in your work?

My father—he was president of the Burlington County [New Jersey] Trust Company—died when I was quite young, but he and Mother were both active in the Quaker movement. Mother was the clerk of the Friend’s Meeting in our hometown. I would say that my parents supported all the ideals that I had.

In 1912 wasn’t it a bit unusual for a woman to receive a Ph.D. degree?

Oh, no. There were no women admitted, of course, to the undergraduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, but there were a number of women graduate students.

When did you actually become involved in suffrage work?

Well, after I got my master’s in 1907, my doctoral studies took me to the School of Economics in London. The English women were struggling hard to get the vote, and everyone was urged to come in and help. So I did. That’s all there was to it. It was the same with Lucy Burns.

You met Miss Burns in London?

Yes, we met in a police station after we were both arrested. I had been asked to go on a little deputation that was being led by Mrs. [Emmeline] Pankhurst to interview the Prime Minister. I said I’d be delighted to go, but I had no idea that we’d be arrested. I don’t know what the charge was. I suppose they hadn’t made all the preparations for the interview with the Prime Minister or something. At any rate, I noticed that Miss Burns had a little American flag pin on her coat, so I went up to her, and we became great friends and allies and comrades. Well, we got out of that, and, of course, afterwards we were immediately asked to do something else. And that way you sort of get into the ranks.

What sort of things were you asked to do?

The next thing I was asked to do was to go up to Norwich and “rouse the town,” as they say. Winston Churchill was in the British cabinet and was going to make a speech there. Well, the English suffragists knew that the government was completely opposed to suffrage, and they conceived this plan to publicly ask all the cabinet members what they were going to do about votes for women. For that moment at least, the whole audience would turn to the subject of suffrage. We considered it an inexpensive way of advertising our cause. I thought it was a very successful method.

What happened at Norwich?

I went to Norwich with one other young woman, who was as inexperienced as I was, and we had street meetings in the marketplace, where everyone assembled for several nights before Mr. Churchill’s speech. I don’t know whether we exactly “roused the town,” but by the time he arrived, I think Norwich was pretty well aware of what we were trying to do. The night he spoke, we had another meeting outside the hall. We were immediately arrested. You didn’t have to be a good speaker, because the minute you began, you were arrested.

Were you a good speaker?

Not particularly. Some people enjoyed getting up in public like that, but I didn’t. I did it, though. On the other hand, Lucy Burns was a very good speaker—she had what you call that gift of the Irish—and she was extremely courageous, a thousand times more courageous than I was. I was the timid type, and she was just naturally valiant. Lucy became one of the pillars of our movement. We never, never, never could have had such a campaign in this country without her.

In her book about the suffrage movement Inez Haynes Irwin tells about your hiding overnight on the roof of St. Andrew’s Hall in Glasgow, Scotland, in order to break up a political rally the next day.

Did Mrs. Irwin say that? Oh, no. I never hid on any roof in my life. In Glasgow I was arrested, but it was at a street meeting we organized there. Maybe Mrs. Irwin was referring to the Lord Mayor’s banquet in London. I think it was in December of 1909, and Miss Burns and I were asked to interrupt the Lord Mayor. I went into the hall, not the night before but early in the morning when the charwomen went to work, and I waited up in the gallery all day. That night Lucy went in down below with the banquet guests. I don’t remember whether she got up and interrupted the mayor. I only remember that I did.

What happened?

I was arrested, of course.

I can’t remember how long I was in jail that time. I was arrested a number of times. As for forcible feeding, I’m certainly not going to describe that.

Well, to me it was shocking that a government of men could look with such extreme contempt on a movement that was asking nothing except such a simple little thing as the right to vote. Seems almost unthinkable now, doesn’t it? With all these millions and millions of women going out happily to work today, and nobody, as far as I can see, thinking there’s anything unusual about it. But, of course, in some countries woman suffrage is still something that has to be won.

Do you credit Mrs. Pankhurst with having trained you in the militant tactics you subsequently introduced into the American campaign?

That wasn’t the way the movement was, you know. Nobody was being trained. We were just going in and doing the simplest little things that we were asked to do. You see, the movement was very small in England, and small in this country, and small everywhere, I suppose. So I got to know Mrs. Pankhurst and her daughter, Christabel, quite well. I had, of course, a great veneration and admiration for Mrs. Pankhurst, but I wouldn’t say that I was very much trained by her. What happened was that when Lucy Burns and I came back, having both been imprisoned in England, we were invited to take part in the campaign over here; otherwise nobody would have ever paid any attention to us.

That was in 1913?

Weren’t you discouraged by the national association’s attitude?

Well, when we came along, we tried to do the work on a scale which we thought, in our great ignorance, might bring some success. I had an idea that it might be a one year’s campaign. We would explain it to every congressman, and the amendment would go through. It was so clear. But it took us seven years. When you’re young, when you’ve never done anything very much on your own, you imagine that it won’t be so hard. We probably wouldn’t have undertaken it if we had known the difficulties.

How did you begin?

I went down to Washington on the seventh of December, 1912. All I had at the start was a list of people who had supported the movement, but when I tried to see them, I found that almost all of them had died or moved, and nobody knew much about them. So we were left with a tiny handful of people.

With all these obstacles how did you manage to organize the tremendous parade that greeted President-elect Wilson three months later?

The press estimated the crowd at a half million. Whose idea was it to have the parade the day before Wilson’s inaugural?

That was the only day you could have it if you were trying to impress the new President. The marchers came from all over the country at their own expense. We just sent letters everywhere, to every name we could find. And then we had a hospitality committee headed by Mrs. Harvey Wiley, the wife of the man who put through the first pure-food law in America. Mrs. Wiley canvassed all her friends in Washington and came up with a tremendous list of people who were willing to entertain the visiting marchers for a day or two. I mention these names to show what a wonderful group of people we had on our little committee.

Did you have any trouble getting a police permit?

No, although in the beginning the police tried to get us to march on Sixteenth Street, past the embassies and all. But from our point of view Pennsylvania Avenue was the place. So Mrs. Ebenezer Hill, whose husband was a Connecticut congressman and whose daughter Elsie was on our committee, she went to see the police chief, and we got our permit. We marched from the Capitol to the White House, and then on to Constitution Hall, which was the hall of the Daughters of the American Revolution, which many of our people were members of.

Didn’t the parade start a riot?

The press reports said that the crowd was very hostile, but it wasn’t hostile at all. The spectators were practically all tourists who had come for Wilson’s inauguration. We knew there would be a large turnout for our procession, because the company that put up the grandstands was selling tickets and giving us a small percentage. The money we got—it was a gift from heaven—helped us pay for the procession. I suppose the police thought we were only going to have a couple of hundred people, so they made no preparations. We were worried about this, so another member of our committee, Mrs. John Rogers, went the night before to see her brother-in-law, Secretary of War [Henry L.] Stimson, and he promised to send over the cavalry from Fort Myer if there was any trouble.

Did you need his help?

Yes, but not because the crowd was hostile. There were just so many people that they poured into the street, and we were not able to walk very far. So we called Secretary Stimson, and he sent over the troops, and they cleared the way for us. I think it took us six hours to go from the Capitol to Constitution Hall. Of course, we did hear a lot of shouted insults, which we always expected. You know, the usual things about why aren’t you home in the kitchen where you belong. But it wasn’t anything violent. Later on, when we were actually picketing the White House, the people did become almost violent. They would tear our banners out of our hands and that sort of thing.

Were you in the front ranks of the 1913 parade?

No. The national board members were at the head of it. I walked in the college section. We all felt very proud of ourselves, walking along in our caps and gowns. One of the largest and loveliest sections was made up of uniformed nurses. It was very impressive. Then we had a foreign section, and a men’s section, and a Negro women’s section from the National Association of Colored Women, led by Mary Church Terrell. She was the first colored woman to graduate from Oberlin, and her husband was a judge in Washington. Well, Mrs. Terrell got together a wonderful group to march, and then, suddenly, our members from the South said they wouldn’t march. Oh, the newspapers just thought this was a wonderful story and developed it to the utmost. I remember that that was when the men’s section came to the rescue. The leader, a Quaker I knew, suggested that the men march between the southern delegations and the colored women’s section, and that finally satisfied the southern women. That was the greatest hurdle we had..

If the parade didn’t cause any real trouble, why was there a subsequent congressional investigation that resulted in the ouster of the district police chief?

The principal investigation was launched at the request of our women delegates from Washington, which was a suffrage state. These women were so indignant about the remarks from the crowd. And I remember that Congressman Kent was very aroused at the things that were shouted at his daughter, Elizabeth, who was riding on the California float, and he was among the first in Congress to demand an investigation into why the police hadn’t been better prepared. As I said, the police just didn’t take our little procession seriously. I don’t think it was anything intentional. We didn’t testify against the police, because we felt it was just a miscalculation on their part.

What was your next move after the parade?

A few weeks after Mr. Wilson became President, four of us went to see him. And the President, of course, was polite and as much of a gentleman as he always was. He told of his own support, when he had been governor of New Jersey, of a state referendum on suffrage, which had failed. He said that he thought this was the way suffrage should come, through state referendums, not through Congress. That’s all we accomplished. We said we were going to try and get it through Congress, that we would like to have his help and needed his support very much. And then we sent him another delegation and another and another and another and another and another and another—every type of women’s group we could get. We did this until 1917, when the war started and the President said he couldn’t see any more delegations.

So you began picketing the White House?

We said we would have a perpetual delegation right in front of the White House, so he wouldn’t forget. Then they called it picketing. We didn’t know enough to know what picketing was, I guess.

How did you finance all this work?

Well, as I mentioned, we were instructed not to submit any bills to the National American. Anything we did, we had to raise the money for it ourselves. So to avoid any conflict with them we decided to form a group that would work exclusively on the Susan B. Anthony amendment. We called it the Congressional Union for Woman’s Suffrage. You see, the Congressional Committee was a tiny group, so the Congressional Union was set up to help with the lobbying, to help with the speechmaking, and especially to help in raising money. The first year we raised $27,000. It just came from anybody who wanted to help. Mostly small contributions. John McLean, the owner of the Washington Post, I think, gave us a thousand dollars. That was the first big gift we ever got.

The records indicate that you raised more than $750,000 over the first eight years. Did your amazing fund-raising efforts cause you any difficulties with the National American?

I know that at the end of our first year, at the annual convention of the National American, the treasurer got up—and I suppose this would be the same with any society in the world—she got up and made a speech, saying, “Well, this group of women has raised a tremendous sum of money, and none of it has come to my treasury,” and she was very displeased with this. Then I remember that Jane Addams stood up and reminded the convention that we had been instructed to pay our own debts, and so that was all there was to it. Incidentally, the Congressional Union paid all the bills of that national convention, which was held in Washington that year. I remember we paid a thousand dollars for the rent of the hall. If you spend a hard time raising the money, you remember about it.

Were you upset about not being reappointed chairman of the Congressional Committee?

No, because they asked me to continue. But they said if I were the committee chairman, I would have to drop the Congressional Union. I couldn’t be chairman of both. Some of the members on the National American board felt that all the work being put into the federal amendment wasn’t a good thing for the entire suffrage campaign. I told them I had formed this Congressional Union and that I wanted to keep on with it.

Was it true, as some historians of the movement maintain, that the National American’s president, Dr. Anna Shaw, was “suspicious” of unusual activity in the ranks?

No, I don’t think she was. She came down to Washington frequently and spoke at our meetings, and she walked at the head of our 1913 procession. But I think we did make the mistake perhaps of spending too much time and energy just on the campaign. We didn’t take enough time, probably, to go and explain to all the leaders why we thought [the federal amendment] was something that could be accomplished. You see, the National American took the position—not Miss Anthony, but the later people—that suffrage was something that didn’t exist anywhere in the world, and therefore we would have to go more slowly and have endless state referendums to indoctrinate the men of the country.

Obviously you didn’t agree with this. Was this what caused the Congressional Union to break with the National American?

We didn’t break with the National American. In a sense we were expelled. At the 1913 convention they made lots and lots of changes in the association’s constitution. I don’t recall what they were, and I didn’t concern myself with the changes at the time. At any rate, the Congressional Union was affiliated with the National American under one classification, and they wrote to us and said if we would resign from that classification and apply for another classification, there would be a reduction in our dues. So we did what they told us, and then when we applied for the new classification, they refused to accept us, and we were out.

Why did the National American do this to your group?

The real division was over the Shafroth-Palmer amendment that the National American decided to substitute for the Anthony amendment in the spring of 1914. Under this proposal each state would hold a referendum on woman suffrage if more than 8 per cent of the legal voters in the last preceding election—males, of course—signed a petition for it. This tactic had been tried without much success before, and with all the time and money such campaigns involve, I don’t think many women would have ever become voters. Our little group wanted to continue with the original amendment, which we called the Susan B. Anthony because the women of the country, if they knew anything about the movement, had heard the name Susan B. Anthony. Now the great part of the American women were very loyal to this amendment, and when the National American suddenly switched to Shafroth-Palmer, we thought that the whole movement was going off on a sidetrack. And that is the reason we later formed the National Woman’s Party, because if we hadn’t continued, there would have been nobody in Washington speaking up for the original amendment.

You didn’t have much faith in state referendums?

The first thing I ever did—after I graduated from Swarthmore, I did some social work in New York City—one of the suffragists there asked me to go with her to get signatures for a suffrage referendum in New York State. So I went with her, and she was a great deal older and much more experienced than I was. I remember going into a little tenement room with her, and a man there spoke almost no English, but he could vote. Well, we went in and tried to talk to this man and ask him to vote for equality for women. And almost invariably these men said, “No, we don’t think that it is the right thing. We don’t do that in Italy, women don’t vote in Italy.” You can hardly go through one of those referendum campaigns and not think what a waste of the strength of women to try and convert a majority of men in the state. From that day on I was convinced that the way to do it was through Congress, where there was a smaller group of people to work with.

Then the National Woman’s Party was formed to continue the work on the federal amendment?

We changed our name from the Congressional Union to the National Woman’s Party in 1916, when we began to get so many new members and branches. Mainly people who disagreed with the National American’s support of the Shafroth-Palmer. And the person who got us to change our name was Mrs. [Alva E.] Belmont.

Would you tell me about Mrs. Belmont?

She was, of course, a great supporter of the suffrage movement financially, and we didn’t even know her the first year we were in Washington. People said to me that she was a wonderfully equipped person who was very fond of publicity, and they suggested that I invite her to come down and sit on one of the parade floats. Well, I didn’t know who she was at all, but I wrote her an invitation, and I remember thinking what a queer person she must be to want to sit on a float. She turned out to be anything but the type she was described, and, of course, she didn’t sit on any float. Anyway, a year later, after we had been expelled from the National American and couldn’t have been more alone and more unpopular and more unimportant, one of our members, Crystal Eastman [Benedict], contacted Mrs. Belmont. And Mrs. Belmont invited me to come have dinner and spend the night at her home in New York City. Well, I like to go to bed early, but Mrs. Belmont was the type that liked to talk all night. So all night we talked about how we could probably get suffrage. A little later Mrs. Belmont withdrew entirely from the old National American and threw her whole strength into our movement. The first thing she did was give us five thousand dollars. We had never had such a gift before.

Why do you think Mrs. Belmont crossed over to your group?

She was entirely in favor of our approach to the problem. She wanted to be immediately put on our national board, so she could have some direction. And then, after suffrage was won, she became the president of the Woman’s Party, and at that time she gave us most of the money to buy the house in Washington that is still the party’s headquarters. Over the years Mrs. Belmont did an enormous amount for the cause of women’s equality. She was just one of those people who were born with the feeling of independence for herself and for women.

Did Mrs. Belmont have something to do with the decision to campaign against the Democrats in the November, 1914, elections?

Yes. You see, here we had an extremely powerful and wonderful man—I thought Woodrow Wilson was a very wonderful man—the leader of his party, in complete control of Congress. But when the Democrats in Congress caucused, they voted against suffrage. You just naturally felt that the Democratic Party was responsible. Of course, in England they were up against the same thing. They couldn’t get this measure through Parliament without getting the support of the party that was in complete control.

Didn’t this new policy of holding the party in power responsible represent a drastic change in the strategy of the suffrage movement?

Up to this point the suffrage movement in the United States had regarded each congressman, each senator, as a friend or a foe. It hadn’t linked them together. And maybe these men were individual friends or foes in the past. But we deliberately asked the Democrats to bring it up in their caucus, and they did caucus against us. So you couldn’t regard them as your allies anymore. I reported all this to the National American convention in 1913, and I said that it seemed to us that we must begin to hold this party responsible. And nobody objected to my report. But when we began to put it into operation, there was tremendous opposition, because people said that this or that man has been our great friend, and here you are campaigning against him.

Would you have taken the same position against the Republicans if that party had been in power in 1914?

Of course. You see, we tried very hard in 1916—wasn’t it [Charles Evans] Hughes running against Wilson that year?—to get the Republicans to put federal suffrage in their platform, and we failed. We also failed with the Democrats. Then we tried to get the support of Mr. Hughes himself. Our New York State committee worked very hard on Mr. Hughes, and they couldn’t budge him. So we went to see former President [Theodore] Roosevelt at his home at Oyster Bay to see if he could influence Mr. Hughes. And I remember so vividly what Mr. Roosevelt said. He said, “You know, in political life you must always remember that you not only must be on the right side of a measure, but you must be on the right side at the right time.” He told us that that was the great trouble with Mr. Hughes, that Mr. Hughes is certainly for suffrage, but he can’t seem to know that he must do it in time. So Mr. Hughes started on his campaign around the country, and when he came to Wyoming, where women were already voting, he wouldn’t say he was for the suffrage amendment. And he went on and on, all around the country. Finally, when he came to make his final speech of the campaign in New York, he had made up his mind, and he came out strongly for the federal suffrage amendment. So it was true what Mr. Roosevelt had said about him.

Do you think Hughes might have beaten Wilson in 1916 if he had come out for suffrage at the beginning of his campaign?

Oh, I don’t know about that. I was just trying to show you that we were always trying to get the support of both parties.

Well, this decision to politically attack the party in power, could this be attributed to the influence of Mrs. Pankhurst and your experience in England?

Maybe, although I didn’t ever really think about it as being that. The key was really the two million women who were already enfranchised voters in the eight western suffrage states. One fifth of the Senate, one seventh of the House, and one sixth of the electoral votes came from the suffrage states, and it was really a question of making the two political parties aware of the political power of women. This was also part of my report to the 1913 National American convention. I said that this was a weapon we could use—taking away votes in the suffrage states from the party in power—to bring both parties around to the federal amendment more quickly.

In the 1914 elections women voted for forty-five members of Congress, and the Democrats won only nineteen of these races, often by drastically reduced pluralities. Weren’t you at all concerned about defeating some of your strongest Democratic supporters in Congress?

Not really. Whoever was elected from a suffrage state was going to be prosuffrage in Congress anyway, whether he was Republican or Democrat. But how else were we going to demonstrate that women could be influential, independent voters? One of the men we campaigned against was Representative—later Senator—Carl Hayden of Arizona, and he finally became a very good friend of the movement, I thought. But it is true that most of them really did resent it very much.

You mean like Representative Taggart of Kansas?

Who? I don’t remember him.

Taggart was the man who attacked you personally at the Judiciary Committee hearings on December 16, 1914. His election majority had been cut from 3,000 in 1912 to 300 in 1914, and when you appeared before the committee to testify on the federal amendment, he said, “Are you here to report the progress of your efforts to defeat Democratic candidates?” He was very upset.

Evidently. But I really don’t remember that, although I know that that feeling was fairly general among the men we had campaigned against. You see, we had so many, many of these hearings. I don’t try to remember them. I sort of wiped them all out of my mind because all of that is past.

I mentioned this particular hearing because the man who came to your defense that day was Representative Volstead, the author of Prohibition, which had a great impact on woman suffrage by removing one of your most vigorous enemies, the liquor lobby.

Oh? I wouldn’t know what you call the liquor lobby, but certainly the liquor interests in the country were represented at the hearings against us. They had some nice dignified name, but they were always there, and I suppose they are still in opposition to our equal-rights amendment. People have the idea that women are the more temperate half of the world, and I hope they are, although I don’t know for sure. The prohibitionists supported our efforts, but I didn’t have any contact with them. And I wasn’t a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union at that time. I’ve since become a member.

By the way, what was the significance of the movement’s official colors?

The purple, white, and gold? I remember the person who chose those colors for us, Mrs. John J. White. She noticed that we didn’t have a banner at the 1913 procession, so she said, “I am going to have a banner made for you, a beautiful banner that will be identified with the women’s movement.” So she had a banner made with these colors, and we agreed to it. There wasn’t any special significance to the choice of colors. They were just beautiful. It may be an instinct, it is with me anyway, when you’re presenting something to the world, to make it as beautiful as you can.

You were once quoted to the effect that in picking volunteers you preferred enthusiasm to experience.

Yes. Well, wouldn’t you? I think everybody would. I think every reform movement needs people who are full of enthusiasm. It’s the first thing you need. I was full of enthusiasm, and I didn’t want any lukewarm person around. I still am, of course.

One of your most enthusiastic volunteers was Inez Milholland Boissevain, wasn’t she?

Inez Milholland actually gave her life for the women’s movement. I think Inez was our most beautiful member. We always had her on horseback at the head of our processions. You’ve probably read about this, but when Inez was a student at Vassar, she tried to get up a suffrage meeting, and the college president refused to let her hold the meeting. So she organized a little group, and they jumped over a wall at the edge of the college and held the first suffrage meeting at Vassar in a cemetery. Imagine such a thing happening at a women’s college so short a time ago. You can hardly believe such things occurred. But they did.

How did Miss Milholland give her life for the movement?

After college Inez wanted to study law, but every prominent law school refused to admit a girl. She finally went to New York University, which wasn’t considered much of a university then, and got her law degree. Then she threw her whole soul into the suffrage movement and really did nothing else but that. Well, in 1916, when we were trying to prevent the re-election of Woodrow Wilson, we sent speakers to all the suffrage states, asking people not to vote for Wilson, because he was opposing the suffrage which they already had. Inez and her sister, Vita, who was a beautiful singer, toured the suffrage states as a team. Vita would sing songs about the women’s movement, and then Inez would speak. Their father, John Milholland, paid all the expenses for their tour, which began in Wyoming. Well, when they got to Los Angeles, Inez had just started to make her speech when she suddenly collapsed and fell to the floor, just from complete exhaustion. Her last words were “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” We used her words on picket banners outside the White House. I think she was about twenty-eight or twenty-nine.

What happened then?

She was brought back and buried near her family home in New York State. We decided to have a memorial service for her in Statuary Hall in the Capitol on Christmas Day. So I asked Maud Younger, who was our congressional chairman and a great speaker, if she would make the principal speech at the ceremony. Maud said she had never made this kind of speech before and asked me how to do it. I remember telling her, “You just go and read Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and then you will know just how.” Maud made a wonderful speech, as she always did.

Did you have any difficulties getting permission to hold the Milholland service in Statuary Hall?

When you have a small movement without much support, you sometimes run into difficulties. I don’t remember any particular difficulty, but we always had them. You just take things in your stride, don’t you think? If you come up against all these obstacles, well, you’ve got to do something about them if you want to get through to the end you have in view. In this case we wanted to show our gratitude to Inez Milholland, and we wanted the world to realize—and I think they did—the importance of her contribution by holding it in the Capitol and having so many people of national importance attend.

Did you invite President Wilson and his family?

Oh, no. We did send a delegation to him from the meeting, but he wouldn’t receive them. Finally on January 9, 1917, he agreed to meet with women from all over the country who brought Milholland resolutions. The women asked him once more to lend the weight and influence of his great office to the federal amendment, but the President rejected the appeal and continued to insist that he was the follower, not the leader, of his party. The women were quite disappointed when they returned to Cameron House, where we had established our headquarters across Lafayette Square from the White House. That afternoon we made the decision to have a perpetual delegation, six days a week, from ten in the morning until half past five in the evening, around the White House. We began the next day.

And this perpetual delegation, or picketing, continued until the President changed his position?

Yes. Since the President had made it clear that he wouldn’t see any more delegations in his office, we felt that pickets outside the White House would be the best way to remind him of our cause. Every day when he went out for his daily ride, as he drove through our picket line he always took off his hat and bowed to us. We respected him very much. I always thought he was a great President. Years later, when I was in Geneva [Switzerland] working with the World Woman’s Party, I was always so moved when I would walk down to the League of Nations and see the little tribute to Woodrow Wilson.

Do you think that the President’s daughters, Jessie and Margaret, who were strong supporters of the suffrage movement, exerted any pressure on the President?

Well, I think if you live in a home and have two able daughters—the third daughter was younger, and I didn’t know much about what she was doing—it would almost be inevitable that the father would be influenced. Also, I think the first Mrs. Wilson was very sympathetic to us, but we never knew Mrs. Gait, his second wife. Someone told me that she wrote a book recently about her life in the White House in which she spoke in the most derogatory terms about the suffragists.

Do you want to talk about the violence that occurred on the White House picket line?

Not particularly. It is true that after the United States entered the war [April 6, 1917], there was some hostility, and some of the pickets were attacked and had their banners ripped out of their hands. The feeling was—and some of our own members shared this and left the movement—that the cause of suffrage should be abandoned during wartime, that we should work instead for peace. But this was the same argument used during the Civil War, after which they wrote the word “male” into the Constitution. Did you know that “male” appears three times in the Fourteenth Amendment? Well, it does. So we agreed that suffrage came before war. Indeed, if we had universal suffrage throughout the world, we might not even have wars. So we continued picketing the White House, even though we were called traitors and pro-German and all that.

Mrs. Irwin wrote in her book that on one occasion a sailor tried to steal your suffrage sash on the picket line and that you were dragged along the sidewalk and badly cut.

Oh, no. She wrote that? No, that never happened. You know, when people become involved in a glorious cause, there is always a tendency, perhaps, to enlarge on the circumstances, to magnify situations and incidents.

And is there, perhaps, on your part a tendency to be overmodest about your activities?

I wouldn’t know about that. All this seems so long ago and so unimportant now, I don’t think you should be taking your precious lifetime over it. I try always, you know, to vanquish the past and try to be a new person.

But it is true, isn’t it, that you were arrested outside the White House on October 20, 1917, and sentenced to seven months in the District of Columbia jail?

Yes.

And that when you were taken to the cell-block where the other suffragists were being held, you were so appalled by the state air that you broke a window with a volume of Robert Browning’s poetry you had brought along to read?

No. I think Florence Boeckel, our publicity girl, invented that business about the volume of Browning’s poetry. What I actually broke the window with was a bowl I found in my cell.

Was this the reason you were transferred to solitary confinement in the jail’s psychopathic ward?

I think the government’s strategy was to discredit me. That the other leaders of the Woman’s Party would say, well, we had better sort of disown this crazy person. But they didn’t.

During the next three or four weeks you maintained your hunger strike. Was this the second or third time you underwent forcible feeding?

Probably, but I’m not sure how many times.

Is this done with liquids poured through a tube put down through your mouth?

I think it was through the nose, if I remember right. And they didn’t use the soft tubing that is available today.

While you were held in solitary confinement your own lawyer, Dudley Field Malone, could not get in to see you. And yet one day David Lawrence, the journalist, came in to interview you. How do you explain this?

I think he was a reporter at that time, but anyway he was a very great supporter of and, I guess, a personal friend of President Wilson’s. I didn’t know then what he was, except that he came in and said he had come to have an interview with me. Of course, a great many people thought that Lawrence, because of his close connection with the White House, had been encouraged to go and look into what the women were doing and why they were making all this trouble and so on.

You and all the other suffragist prisoners were released on November 27 and 28, just a few days after Lawrence’s visit. Could this action have been based on his report to the President?

I wouldn’t know about that. Of course, the only way we could be released would be by act of the President.

And on January 9, 1918, President Wilson formally declared for federal suffrage. The next day the House passed the amendment 274-136, and the really critical phase of the legislative struggle began.

Yes. Well, when we began, Maud Younger, our congressional chairman, got up this card catalogue, which is now on loan to the Library of Congress. We had little leaflets printed, and each person who interviewed a congressman would write a little report on where this or that man stood. We knew we had the task of winning them over, man by man, and it was important to know what our actual strength was in Congress at all times. These records showed how, with each Congress, we were getting stronger and stronger, until we finally thought we were at the point of putting the Anthony amendment to a vote. And of course this information was very helpful to our supporters in Congress.

Yet when the Senate finally voted on October 1, 1918, the amendment failed by two votes of the necessary two thirds. What happened?

We realized that we were going to lose a few days before the vote. We sat there in the Senate gallery, and they talked on and on and on, and finally Maud Younger and I went down to see what was going on, why they wouldn’t vote. People from all over the country had come. The galleries were filled with suffragists. We went to see Senator Curtis, the Republican whip, and the Republican leader, Senator Gallinger. It was then a Republican Senate. And there they stood, each with a tally list in their hands. So we said, why don’t you call the roll. And they said, well, Senator Borah has deserted us, he has decided to oppose the amendment, and there is no way on earth we can change his mind.

You thought Borah was on your side?

Oh, yes. He wanted our support for his re-election campaign that year out in Idaho, and our organizer out there, Margaret Whittemore, had a statement signed by him that he would vote for the suffrage amendment. But then he changed. He never gave any reason for changing.

Did you then oppose him in the November election?

We opposed him, yes. We cut his majority, but he was reelected, and from a suffrage state.

Was it about this time that your members began burning the President’s statements in public?

I’m not sure when it started. We had a sort of perpetual flame going in an urn outside our headquarters in Lafayette Square. I think we used rags soaked in kerosene. It was really very dramatic, because when President Wilson went to Paris for the peace conference, he was always issuing some wonderful, idealistic statement that was impossible to reconcile with what he was doing at home. And we had an enormous bell—I don’t recall how we ever got such an enormous bell—and every time Wilson would make one of these speeches, we would toll this great bell, and then somebody would go outside with the President’s speech and, with great dignity, burn it in our little caldron. I remember that Senator Medill McCormick lived just down the street from us, and we were constantly getting phone calls from him saying they couldn’t sleep or conduct social affairs because our bell was always tolling away.

You had better results from the next Congress, the Sixty-sixth, didn’t you?

Yes. President Wilson made a magnificent speech calling for the amendment as a war measure back in October, 1918, and on May 20, 1919, the House passed the amendment. Then on June 4 the Senate finally passed it.

Did you go to hear the President?

I don’t believe we were there, because when the President spoke, everybody wanted tickets, and the Woman’s Party has never asked for tickets, because we still don’t want to be in any way under any obligation. I know we were in the gallery when the Senate actually voted, because nobody wanted tickets then. Our main concern was that the Senate might try to reinstate the seven-year clause that had been defeated in the House.

The seven-year clause?

This clause required the amendment to be ratified by the states within seven years or else the amendment would be defeated. We got the clause eliminated on the suffrage amendment, but we were unable to stop Congress from attaching it to the present equal-rights amendment.

Were you relieved when the Anthony amendment finally passed?

Yes, for many reasons. But we still had to get it ratified. We went to work on that right away and worked continuously for the fourteen months it took. But that last state … we thought we never would get that last state. And, you know, President Wilson really got it for us. What happened was that Wilson went to the governor of Tennessee, who was a Democrat. The President asked him to call a special session of the state legislature so the amendment could be ratified in time for women to vote in the 1920 Presidential election.

That was on August 18, 1920, and there is a well-known photograph of you, on the balcony of your headquarters, unfurling the suffrage flag with thirty-six stars. What were your feelings that day?

You know, you are always so engrossed in the details that you probably don’t have all the big and lofty thoughts you should be having. I think we had this anxiety about how we would pay all our bills at the end. So the first thing we did was to just do nothing. We closed our headquarters, stopped all our expenses, stopped publishing our weekly magazine, The Suffragist, stopped everything and started paying off the bills we had incurred. Maud Younger and I got the tiniest apartment we could get, and she took over the housekeeping, and we got a maid who came in, and we just devoted ourselves to raising this money.

What happened to Lucy Burns, your co-leader?

Well, she went back, I guess, to her home in Brooklyn. Everybody went back to their respective homes. Then the following year, on February 15, 1921, we had our final convention to decide what to do. Whether to disband or whether to continue and take up the whole equality program—equality for women in all fields of life—that had been spelled out at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848. We decided to go on, and we elected a whole new national board, with Elsie Hill as our new chairman. We thought we ought to get another amendment to the Constitution, so we went to many lawyers—I remember we paid one lawyer quite a large sum, for us, at least—and asked them to draw up an amendment for equal rights. We had another meeting up in Seneca Falls on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the original meeting, and there we adopted the program we have followed ever since on the equal-rights amendment. That was 1923. So that is when we started.

Was that the year the first equal-rights amendment was introduced?

We hadn’t been able to get any lawyer to draft an amendment that satisfied us, so I drafted one in simple ordinary English, not knowing anything much about law, and we got it introduced in Congress. But at the first hearing our little group was the only one that supported it. All these other organizations of women that hadn’t worked to get the vote, these professional groups and so on, opposed the amendment on the grounds that it would deprive them of alimony and force them to work in the mines, and they would lose these special labor laws that protect women. So it was obvious to us—and to the Congress—that we were going to have to change the thinking of American women first. So we began going to convention after convention of women, trying to get them to endorse E.R.A. It took many years. The American Association of University Women just endorsed it in 1972. Imagine, all the years and years and years that women have been going to universities. But the new generation of college women were so hopeless on this subject.

It was like forty years in the wilderness, wasn’t it?

Yes, more or less. But during that time we opened—and by “we” I mean the whole women’s movement—we opened a great many doors to women with the power of the vote, things like getting women into the diplomatic service. And don’t forget we were successful in getting equality for women written into the charter of the United Nations in 1945.

Do you think the progress of the equal-rights amendment has been helped by the women’s liberation movement?

I feel very strongly that if you are going to do anything, you have to take one thing and do it. You can’t try lots and lots of reforms and get them all mixed up together. Now, I think the liberation movement has been a good thing, because it has aroused lots of women from their self-interest, and it has made everyone more aware of the inequalities that exist. But the ratification of the equal-rights amendment has been made a bit harder by these people who run around advocating, for instance, abortion. As far as I can see, E.R.A. has nothing whatsoever to do with abortion.

How did abortion become involved with equal rights?

At the 1968 Republican convention our representative went before the platform committee to present our request for a plank on equal rights, and as soon as she finished, up came one of the liberation ladies, a well-known feminist, who made a great speech on abortion. So then all the women on the platform committee said, well, we’re not going to have the Republican Party campaigning for abortion. So they voted not to put anything in the party platform about women’s rights. That was the first time since 1940 that we didn’t get an equal-rights plank in the Republican platform. And then that feminist showed up at the Democratic convention, and the same thing happened with their platform. It was almost the same story at the 1972 conventions, but this time we managed to get equal rights back into the platforms.

It‘s really the principle of equal rights that you’re concerned with, isn’t it, not the specific applications?

I have never doubted that equal rights was the right direction. Most reforms, most problems are complicated. But to me there is nothing complicated about ordinary equality. Which is a nice thing about our campaign. It really is true, at least to my mind, that only good will come to everybody with equality. If we get to the point where everyone has equality of opportunity—and I don’t expect to see it, we have such a long, long way ahead of us—then it seems to me it is not our problem how women use their equality or how men use their equality.

Miss Paul, how would you describe your contribution to the struggle for women’s rights?

I always feel … the movement is a sort of mosaic. Each of us puts in one little stone, and then you get a great mosaic at the end.