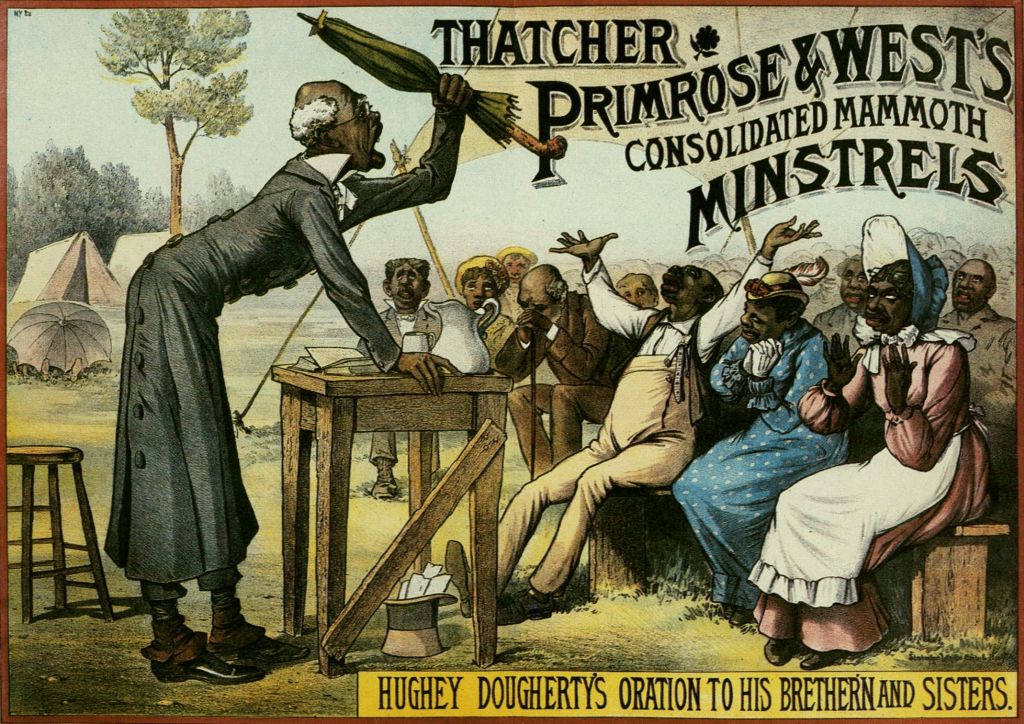

In the 19th Century, white performers invented the minstrel show, the first uniquely American entertainment form

-

April/May 1978

Volume29Issue3

NOTE: this article has been updated and reissued in the Winter 2019 issue. Click for the new version.

It is on our supermarket shelves, in our advertising, and in our literature. But most of all, it is in our entertainment. From Aunt Jemima to Mammy in Gone With the Wind, from Uncle Remus to Uncle Ben, from Amos ‘n’ Andy to Good Times, the inexplicably grinning black face is a pervasive part of American culture. Only recently have black performers been able to break out of the singing, dancing, and comedy roles that have for so long perpetuated the image of blacks as a happy, musical people who would rather play than work, rather frolic than think. Such images have inevitably affected the ways white America has viewed and treated black America. Their source was the minstrel show.

Before the Civil War, American show business virtually excluded black people. But it never ignored black culture. In fact, the minstrel show—the first uniquely American entertainment form—was born when Northern white men blacked their faces, adopted heavy dialects, and performed what they claimed were black songs, dances, and jokes to entertain white Americans. No one took minstrel shows seriously; they were meant to be light, meaningless entertainment.

But it was no accident that the blackface minstrel show developed in the decades before the Civil War, when slavery was often the central public issue, no accident that it dominated show business until the 1880’s, when white America made crucial decisions about the status of blacks, and no accident that after the minstrel show died, the basic stereotypes it had nurtured endured-the happy, banjo-strumming plantation “darky,” the loving loyal mammy and old uncle, the lazy, good-for-nothing buffoon, the pretentious city slicker.

For better or worse, the American people made the minstrel show what it was.

America’s cities mushroomed after 1820, and American show business grew along with them. The new city audiences were large, boisterous, and hungry for entertainment; they hollered, hissed, cheered, and booed with the intensity and fervor of today’s football fans, and shrewd impresarios quickly learned to give them what they wanted. Between the acts of every play, whether it was Hamlet or the Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized and Demi-Savage Extravaganza of Pocahontas , audiences were treated to short variety turns of songs, dances, and comedy.

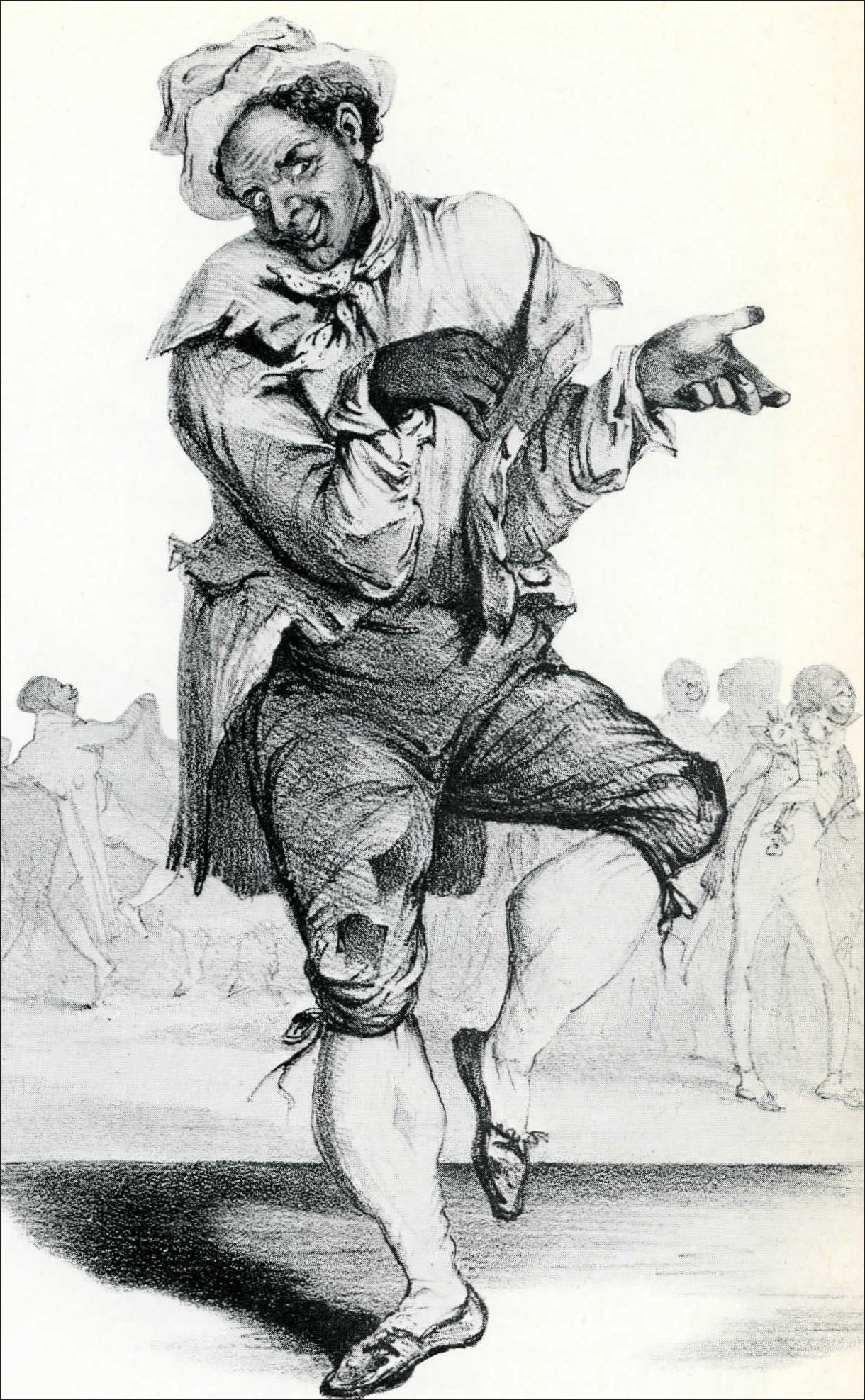

Between-the-act performers drew heavily on American folklore and folk song, so it was no surprise that the unique culture of black Americans became a regular feature of these brief skits. The only surprise might have been that the performers were white men wearing burnt-cork make-up. But before the Civil War, blacks were rarely allowed on the popular stage, just as they were rarely allowed in white hotels, restaurants, courthouses, or cemeteries.

As early as the 1820’s, some white performers specialized in what they called “Ethiopian delineation.” The Ethiopian delineators were entertainers, not anthropologists, of course, and they had no particular interest in the authenticity of their performances. But they had an insatiable appetite for fresh black material that could be shaped into popular stage acts.

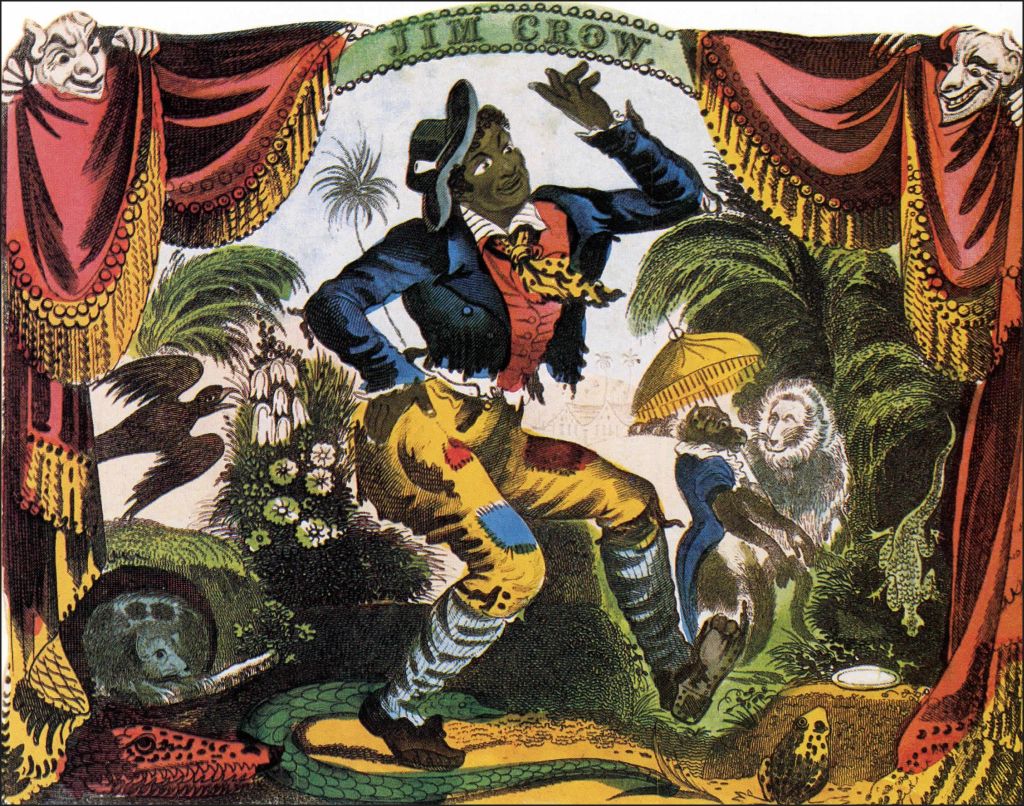

Appearing in Louisville, Kentucky, about 1828, Thomas D. “Daddy” Rice, a blackface performer, saw a crippled black stablehand doing a peculiar shuffling, hopping dance. The stablehand’s name was Jim Crow, and as he danced he sang a catchy song with the refrain: Weel about, and turn about/And do jus so;/ Eb’rytime I weel about/I jump Jim Crow . Rice knew a good thing when he saw one; he memorized the stablehand’s song, copied his hobbling dance, wrote some new verses, and tried out the routine on stage. He was an immediate hit in the Ohio River Valley and was soon “Jumping Jim Crow” to a standing-room-only crowd of over thirty-five hundred in New York’s Bowery Theater.

The “Jim Crow” song and dance, observed writer Y. S. Nathanson in 1855, “touched a chord in the American heart which had never before vibrated.” It brought black culture to white Americans, who could no more resist the urge to try the new black dances of the 1830’s than their twentieth-century descendants could resist trying new black dances, from the Charleston to the Hustle and beyond. Nathanson recalled seeing a “young [white] lady in a sort of inspired rapture, throwing her weight alternately upon the tendon Achilles of the one, and the toes of the other foot, her left hand resting upon her hip, her right… extended aloft, gyrating as the exigencies of the song required, and singing Jim Crow at the top of her voice.”

Spurred on by Rice’s phenomenal success, many blackface performers in the 1830’s did primitive fieldwork among black people. Billy Whillock, who toured the South with circuses in the 1830’s, would “steal off to some negro hut to hear the darkies sing and see them dance, taking a jug of whisky to make things merrier.” Ben Cotton, another blackface star, also recalled studying black culture at its source: “I used to sit with them in front of their cabins, and we would start the banjo twanging, and their voices would ring out in the quiet night air in their weird melodies.” Similarly, E. P. Christy, later the leader of the famous Christy Minstrels, was fascinated with the “queer words and simple but expressive melodies” he heard from black dock workers in New Orleans.

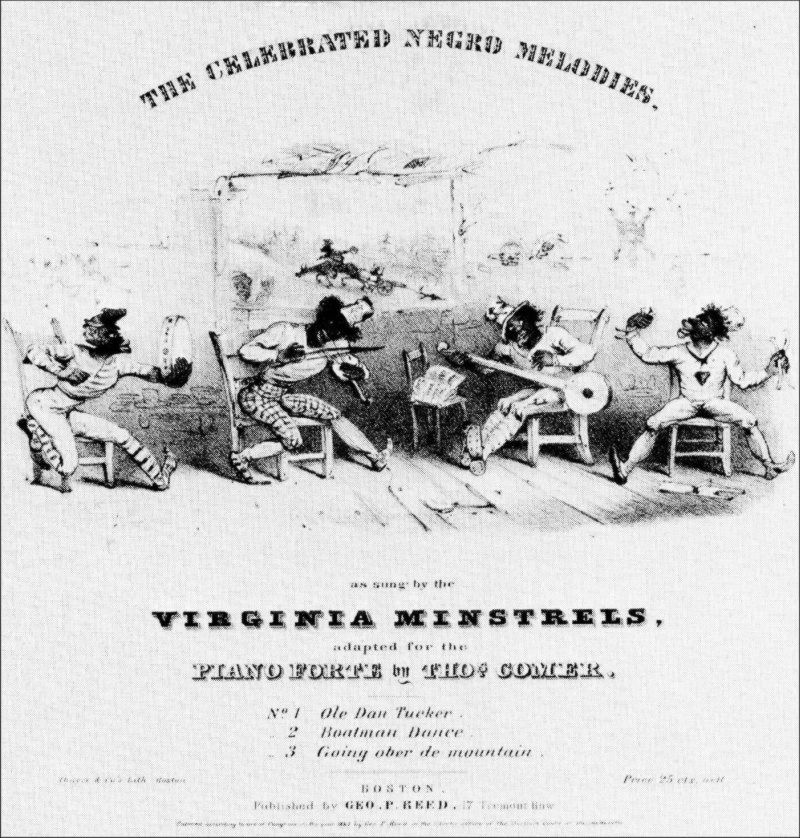

In the winter of 1842-43, four Ethiopian delineators—Billy Whitlock, Frank Pelham, Frank Brower, and Dan Emmett—found themselves in New York City “between engagements.” Single bookings were hard to find, so they decided to unite and stage the first entire show of blackface entertainment. Calling themselves the Virginia Minstrels, they were an instant sensation. Soon there were minstrel troupes almost everywhere. In 1844 the Ethiopian Serenaders played before President John Tyler at the White House. Eight years later, Buckley’s Serenaders performed in the new state of California. In New York City, a synagogue was converted into Wood’s Minstrel Hall, one of at least ten major minstrel houses in the city in the 1850’s. And when Commodore Perry’s fleet forced its way into Japan, his crew chose to introduce American culture with a minstrel show.

During the next half century, the minstrel show would be the most popular form of entertainment in America, for it was perfectly suited to the tastes of everyday Americans. As the upbeat overture quieted the noisy crowd and the curtain rose, the eight minstrels would burst into action, strutting, singing, waving their arms, banging their tambourines, and prancing around a semicircle of chairs. Finally the dignified man in the middle, the interlocutor, established order by commanding: “Gentlemen, be seated!” “Mr. Bones,” the interlocutor said, enunciating clearly as he turned toward the “end” man, a comedian with grotesque, pop-eyed, grinning make-up, “I understand you went to the ball game yesterday afternoon. You told me you wanted to go to your mother-in-law’s funeral.” “I did want to,” the end man shot back, “but she ain’t dead yet.”

More jokes followed before the interlocutor introduced a handsome tenor, who sang “Mother I’ve Come Home to Die,” or some similar sentimental ballad. “These mournful ditties form the staple of the first part,” wrote one fan in 1879. “But there is occasionally a rattling comic song by Brudder Bones. He dances to the tune, he throws open the lapel of his coat, and in a final spasm of delight, he stands upon his head on the chair seat and for a thrilling and evanescent instant extends his nether extremities in the air.”

At the intermission the patrons had another drink while the minstrels changed out of their formal wear in preparation for the olio, a variety show which included “banjoists; men with performing dogs or monkeys; Hottentot overtures;… song and dance men; the water-melon man; persons who play upon penny whistles, combs, Jew’s-harps, bagpipes, quills, their fingers—individuals, in fact, who do every thing by turns, but nothing long.” For part three, the curtain rose on a plantation scene complete with cotton bales, a white-columned house, a smoking steamboat, and blackface “darkies.” A banjo rang out, signaling the beginning of a raucous party that concluded with the entire troupe singing “the wild bars of some plantation tune,” dancing wildly, and doing “any grotesquerie, so long as it is not indecent.” The audience joined in until the theater shook with foot-stomping, hand-clapping, singing, dancing, laughing people.

Minstrelsy produced some of America’s most beloved and enduring popular songs-“Jim Along Josey,” “De Blue Tail Fly,” “Dance, Boatman, Dance,” “Turkey in the Straw,” “Dixie”— and it gave America the melodies of Stephen Foster. Born in Pittsburgh in 1826, Foster was exposed in his youth to all types of music. His family taught him the refined, genteel music heard in respectable parlors; the family’s Negro servant took him to her church, where he heard spirituals; and he blacked up to sing songs like “Jump Jim Crow” in a local theater.

Foster's genius as a songwriter was that he combined the qualities of black and white folk music in songs that were easy to sing and play. Beginning in 1848, minstrels made many of his songs into national hits, including “Camptown Races,” “Old Folks at Home,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Old Black Joe,” and “Beautiful Dreamer.”

Minstrel humor ranged from skits to one-liners, from slapstick to riddles. End men explained that the letter t was like an island, because it was in the middle of “water”; that a man who fell off a boat used a bar of soap to wash himself ashore; that firemen wore red suspenders to hold up their pants; and that chickens crossed the road to get to the other side. In this punchy language play, minstrels were beginning to introduce the rapid-fire humor of the city, the humor later perfected in vaudeville, burlesque, and radio.

“My new place does not have a single bug,” end man Charlie Fox boasted in 1859 about his boardinghouse. “All of them are married and have large families.”

Minstrels also performed long comic monologues, “stump speeches” which depended on the foolish misuse of language rather than anecdotes or plot for laughs: Transcendentalism is dat spiritual cognoscence ob pyschological irrefragibility, connected wid conscientient ademption ob incolumbient spirituality and etherialized connection … dat became ana-tomi-cati-cally tattalable in de circum ambulatin commotion ob ambiloquous voluminiousness . Besides mocking pretentious blacks for being “better stocked with words than Judgement,” stump speeches also poked fun at pompous politicians and professionals who seemed to talk in such gobbledygook.

Minstrel slapstick could be quite elaborate. In one act, a cast of sleepwalkers—a super-patriotic politician, a passionate lover, a quick-fingered kleptomaniac, and a “canine hydrophobia patient” who thought he had been bitten by a rabid dog—roamed the stage, acting out their obsessions in their sleep while a burglar tried to tiptoe among them without waking them up. Finally, the canine hydrophobiac pounced on the thief, biting, snarling, and barking as the stage exploded with action and real fireworks.

With America’s best songwriters, comics, singers, dancers, and novelty acts, the minstrel show offered more than enough lively variety entertainment to ensure its popularity. But it was not just the nation’s first top-notch variety show. It was a top-notch variety show performed in blackface and black dialect. Race was a central part of its initial and enduring appeal.

The Northern white public before the Civil War generally knew little about black people. But it knew that it did not welcome blacks as equals and that it did enjoy watching minstrels portray the “oddities, peculiarities, eccentricities, and comicalities of that Sable Genus of Humanity.” With their ludicrous dialects, grotesque make-up, bizarre behavior, and simplistic caricatures, minstrels portrayed blacks as totally inferior. Minstrels created two sets of contrasting stereotypes—the happy, frolicking plantation darkies and the foolish, inept urban fools.

In their plantation material, minstrels concentrated on the fun and games of slave life—what the Virginia Minstrels described as “the Sports, and Pastimes of the Virginia Colored Race.” This made for an entertaining show, but it also meant presenting slaves as happy, dancing children for whom life was a continual frolic. Beginning with Christy’s in 1853, minstrels even turned Harriet Beecher Stowe’s popular antislavery novel and play Uncle Tom’s Cabin into Happy Uncle Tom, a plantation farce about the joys of living in the old Kentucky home:

Oh, white folks, we’ll have you to know

Dis am not de version of Mrs. Stowe;

Wid her de Darks am all unlucky

But we am de boys from Old Kentucky.

Den hand de Banjo down to play

We‘ll make it ring both night and day

And we care not what de white folks say

Dey can’t get us to run away.

In the minstrel shows, “darkies” (they rarely used the more disturbing word “slaves”) “tink ob nuthin but to play.”

The stereotyped plantation was also the home of an idealized, interracial family: master and mistress were the loving parents and all the darkies, regardless of age, their children. The most popular black members of this family were the mammy and the old uncle, specialty roles that provided some minstrels with long, successful careers. Milt Barlow was a star for thirty years playing “old darkies,” from Old Black Joe to Uncle Remus. Many of the minstrels’ most popular and moving songs celebrated the allegedly close bonds between masters and their old slaves. In Stephen Foster’s “Massa’s in de Cold, Cold Ground,” “all de darkeys am a-weeping” because the kind master they dearly loved had died and left them behind. These aging black folks stood for the loyalty, love, and family values the minstrel plantation preserved in a mythic setting.

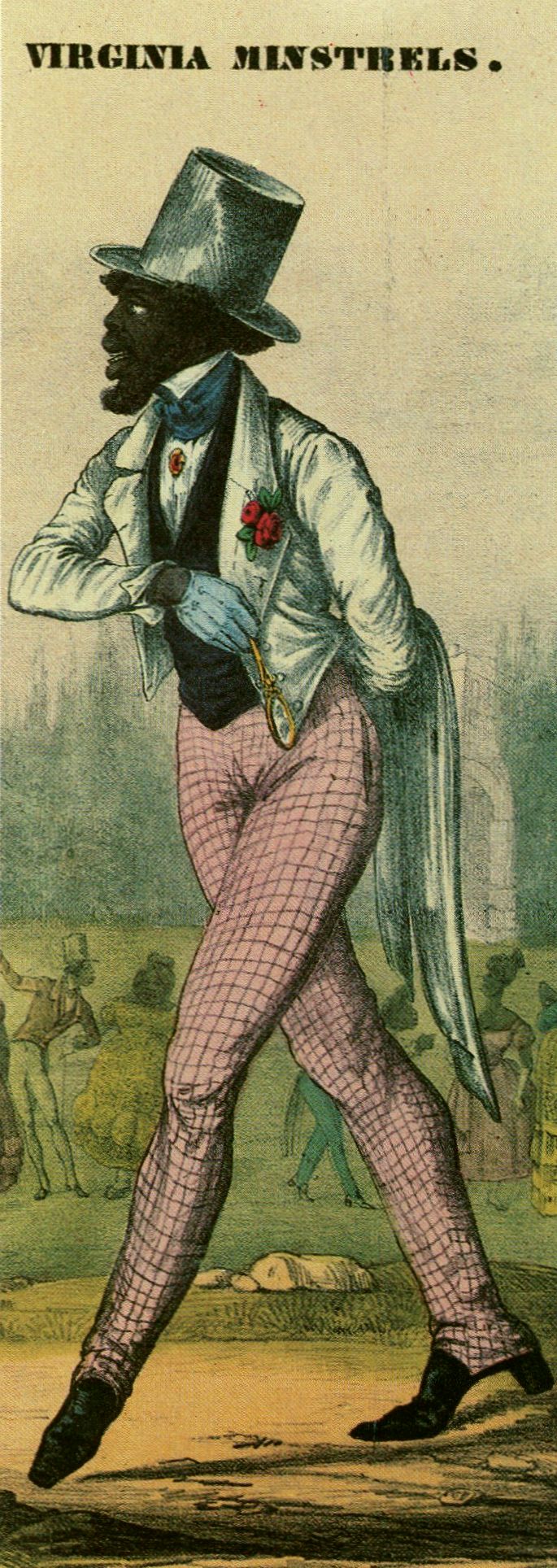

In minstrel shows, blacks lived either on Southern plantations where they were contented and secure, or in Northern towns where they were bewildered and insecure-which is probably very much the way life seemed to the many minstrel fans who had recently moved from farms to cities. But minstrelsy’s Northern black characters were not just common people suffering the anxieties of urban life. They were ignorant, bumbling buffoons who were totally out of place outside the South. A black brakeman on a train spent all day breaking into luggage. A drunk claimed he was a lawyer because of all the practicing he had done at the bar. A cook hung up toast to dry. And black soldiers, when ordered to “fall in,” fell into a lake. No one in the audience could have been as stupid as these hapless dolts; the spectacle they presented allowed white audiences to laugh-and look down-at blacks. The other major minstrel stereotype of Northern Negroes was the prancing dandy who thought only of flirting, fun, and fashion. Wearing skintight “trousaloons,” a long-tailed coat with wide, padded shoulders, a high ruffled collar, white gloves, a long, gold watch chain, and a shining monocle, Count Julius Caesar Mars Napoleon Sinclair Brown and other fops not only showed how absurd blacks could be when they tried to live like white “gemmen,” but also gave white common people a chance to ridicule upper-crust white dandies.

The minstrel show’s message was that black people belonged only on Southern plantations and had no place at all in the North. “Dis being free,” complained one minstrel character who had run away from the plantation, “is worser dem being a slave.” Songs like Dan Emmett’s “Dixie,” a Northern minstrel song which was introduced in New York City in 1859 by Bryant’s Minstrels, underscored these messages by having Northern blacks wish they were in the land of cotton. “Dixie” was a great hit in the North before it became the unofficial Confederate national anthem. Even after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, minstrels and their public still sang of blacks pining for the old plantation.

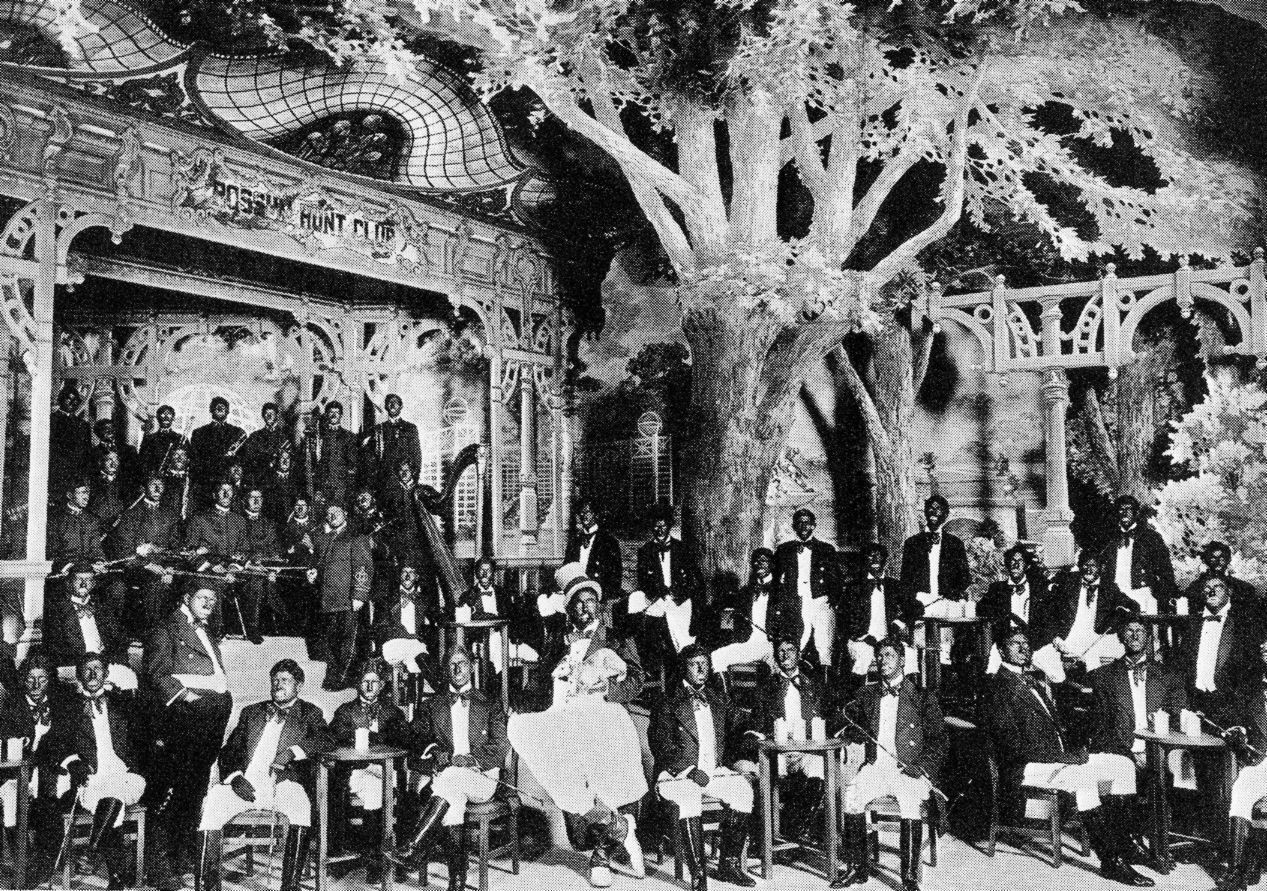

For decades, minstrels had few show-business competitors. But beginning in the 1870’s, they faced serious competition in cities from large-scale musical comedies and variety shows. In response, J. H. Haverly, the greatest minstrel promoter of them all, created his United Mastodon Minstrels, which, instead of eight or ten performers and two end men, boasted “Forty—40- Count ‘Em-40-Forty” minstrels and eight end men. In 1880 the Mastodons featured a “magnificent scene representing a Turkish Barbaric Palace in Silver and Gold” that included Turkish soldiers marching, a Sultan’s palace, and “Base-Ball.” And that was just one feature of the first part of the show. After a longolio, the program closed with “Pea-Tea-Bar-None’s Kollosal, Cirkuss, Museum, Menagerie and Kayne’s Kickadrome Kavalkade,” a parody of Barnum’s circus that included equestrians, clowns, tightrope walkers, and “trained elephants.”

Haverly also made his minstrels a national touring company, instead of a resident urban troupe as earlier minstrels had been. His handsomely outfitted minstrels, led by a blaring brass band, paraded grandly through every town they entered. Other minstrels followed Haverly’s formula, taking to the road, mounting lavish productions, and shifting away from plantation and black material. Some late-nineteenth-century troupes, like those led by George Primrose and William West, “The Millionaires of Minstrelsy,” even began to perform without blackface make-up. “We were looking for novelty,” recalled George Thatcher, a star of that troupe, “and for a change tried white minstrelsy” with the cast in “Shakespearian costumes.” It was not just novelty and other entertainment forms that forced such changes.

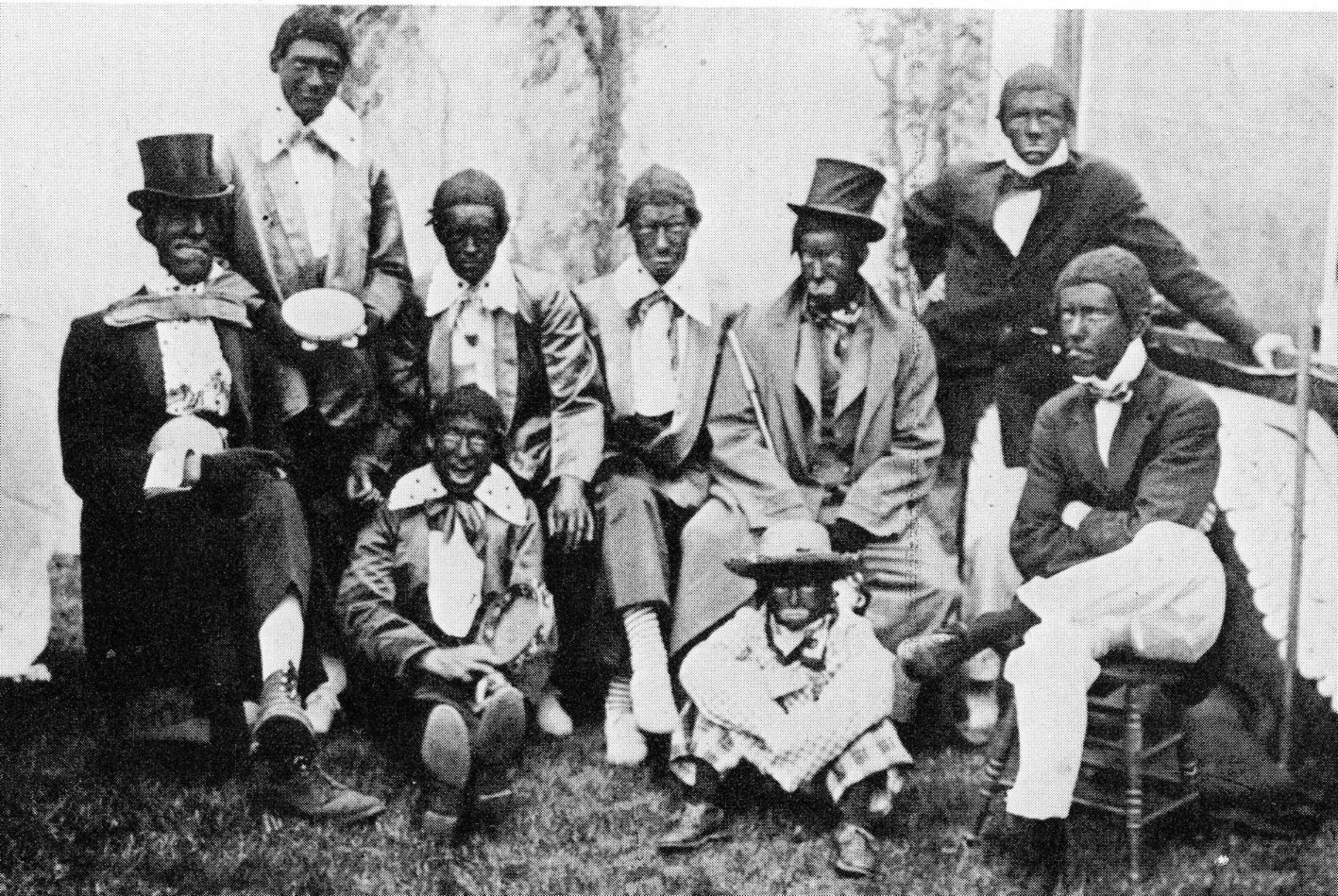

After the Civil War, large numbers of black performers broke into American show business as minstrels. To do so, they had first to win white audiences away from white minstrels. The way they did it set an enduring pattern for black entertainers. Brooker and Clayton’s Georgia Minstrels, the first successful black troupe, billed itself in 1865-66 as “The Only Simon Pure Negro Troupe in the World” and claimed that it was “composed of men who during the war were SLAVES IN MACON, GEORGIA, who, having spent their former life in Bondage … will introduce to their patrons PLANTATION LIFE in all its phases.”

Other black minstrels also stressed their race, claiming to be ordinary ex-slaves doing what came naturally, rather than skilled entertainers acting out white-created stereotypes of blacks. By the 1870’s, black minstrels had become the acknowledged experts in plantation material. One white critic even attacked the white minstrel as “at best a base imitator.” But the public still wanted the same old stereotypes. “The success of the [black] troupe,” one reviewer baldly stated, “goes to disprove the saying that the negro cannot act the nigger.” “Acting the nigger” was exactly what white audiences expected and demanded of black performers.

“It was a big break when show business started [for blacks],” observed black minstrel Tom Fletcher. “Salaries were not large, but they still amounted to much more than they were getting [before] and there was the added advantage of opportunity to travel.…” “All the best [black] talent of that generation came down the same drain,” recalled W. C. Handy, the composer of “St. Louis Blues” and countless other songs, who began his long career as a black minstrel. “The composers, the singers, the musicians, the speakers, the stage performers-the minstrel show got them all.” They had no choice. Because of minstrelsy, then, black people became part of American show business. Initially, they were limited to stereotyped roles and given little credit for their performing skills. But they had a foot in the door and could begin their long struggle to modify and break free of the patterns and images imposed on them by white minstrels.

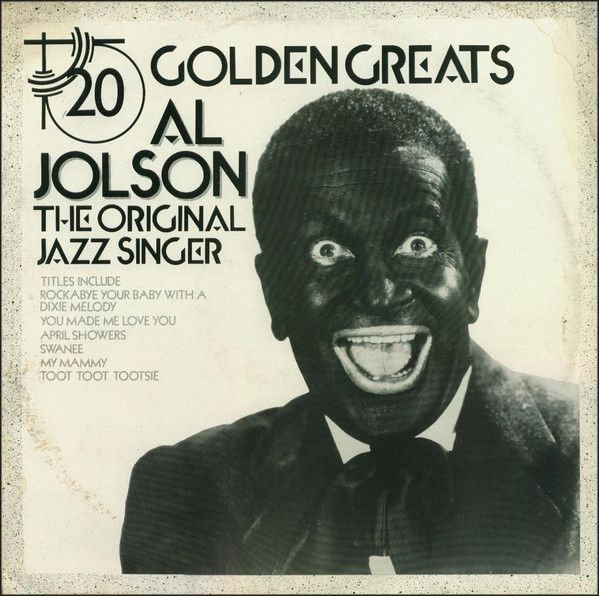

By the turn of the twentieth century, as major changes in society produced major changes in show business, the minstrel show’s popularity began to wane. With the reunification of the North and the South, public interest and concern was shifting from minstrelsy’s plantation topics to industrial and urban problems and to the influx of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Minstrels adapted their material to these changes as best they could. But their blackface make-up limited the effectiveness of their portrayal of immigrants, and they lost their identity as minstrels if they discarded the burnt cork. Eventually, the blackface act, kept alive by stars like Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, became just one of many standard vaudeville and musical-comedy turns; the minstrel show disappeared-but not the stereotyped black mask behind which lay the uncomfortable reality of African-American life in America.