It's often portrayed as an orderly conflict between patriots, Tories, and British, but the American Revolution caused much suffering, dislocation, and economic decline, and had major effects on Native Americans and Spanish, French, Dutch, and other colonists worldwide.

-

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2017

Volume62Issue4

Alan Taylor, in his recent American Revolutions: A Continental History, provides an important international context for the War for Independence, a perspective that is too often lacking in general discussions about the conflict. Taylor weaves the perspectives of France, Spain, and the various Native tribes into a sweeping narrative that continues through the period into the early republic, as Jefferson's "empire of liberty" expands to the west and sets the stage for later events. The book is a sort of "prequel" for Taylor's previous book, The Civil War of 1812, about the important and under-studied War of 1812. Taylor is the Thomas Jefferson Professor of History at the University of Virginia, has twice won the Pulitzer Prize for history, and was a finalist for the National Book Award. He previously wrote about Pontiac's War for American Heritage.

May not a man have several voices, Robin,

as well as two complexions?

—NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, from “My Kinsman, Major Molineux”

0n a summer evening, a rustic “youth of barely eighteen years” arrived in a seaport capital, “the little metropolis of a New England colony.” Although dressed in homespun and having little money, Robin was handsome, alert, and ambitious. The clever son of a country clergyman, he came to seek his celebrated kinsman, Major Molineux, a wealthy gentleman in royal favor. With the major’s patronage, Robin expected to rise quickly in society. Passing through “a succession of crooked and narrow streets,” he became confused and angry when no one would direct him to his kinsman’s mansion. Instead, people mocked Robin. At last, a stranger replied, “Watch here an hour, and Major Molineux will pass by.” Robin noticed the stranger’s face painted half black and half red “as if two individual devils, a fiend of fire and a fiend of darkness, had united themselves to form this infernal visage.”

The young man waited by a moonlit church, where he encountered “a gentleman in his prime, of open, intelligent, cheerful, and altogether prepossessing countenance.” Learning of Robin’s mission, the gentleman lingered from “a singular curiosity to witness your meeting.” In the distance, they heard the advancing roar of a crowd. “There were at least a thousand voices went up to make that one shout,” Robin noted. “May not a man have several voices, Robin, as well as two complexions?” the gentleman replied.

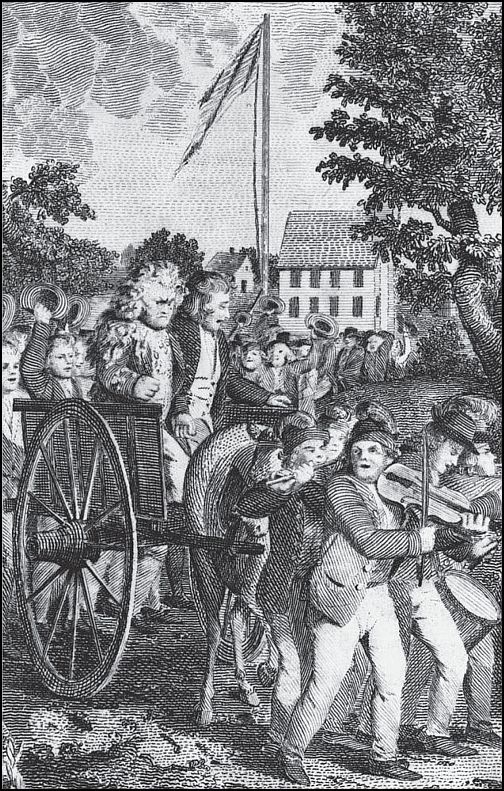

The painted stranger reappeared at the head of a torch-lit parade of “wild figures in the Indian dress” attended by raucous musicians and “applauding spectators,” including women. The cavalcade accompanied an open cart holding “an elderly man, of large and majestic person” covered with tar and feathers. Robin recognized the victim as his kinsman suffering from “overwhelming humiliation.” His face was “pale as death . . . his eyes were red and wild, and the foam hung white upon his quivering lip.” The rioters halted and fell silent, looking to Robin for reaction, and the major recognized his kinsman. “They stared at each other in silence, and Robin’s knees shook, and his hair bristled, with a mixture of pity and terror.” Suddenly, Robin felt “a bewildering excitement” as he erupted into a loud and long laugh shared with the mob at the major’s expense. The rioters marched on “like fiends that throng in mockery around some dead potentate, mighty no more, but majestic still in his agony.”

As the street reclaimed silence, the watching gentleman asked, “Well, Robin, are you dreaming?” Having lost all hope of patronage from his disgraced kinsman, Robin prepared to leave town, but the gentleman advised Robin to stay “as you are a shrewd youth, you may rise in the world without the help of your kinsman, Major Molineux.”

A story published by Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1832, “My Kinsman, Major Molineux” specifies neither dates nor places and names no historical characters, operating instead as a dreamy metaphor rich in symbol and suggestion. But nothing done since by historian or novelist so concisely conveys the internal essence of the revolution. Hawthorne recognized that the struggle was our first civil war, rife with divisions, violence and destruction. The fiends of fire and darkness were busy during the revolution.

Hawthorne understood the power of stylized violence to compel the wavering to endorse revolution. Patriots built popular support, and intimidated opponents, through rituals that invited public participation to shame others. Robin’s sudden laugh represents the decisions made by thousands when they helped to disgrace Loyalists as enemies to American liberty.

Historians and politicians often miscast the American Revolution as the polar opposite of even bloodier revolutions elsewhere. They recall the American version as good, orderly, restrained, and successful when contrasted against the excesses of the French and Russian revolutions. Polarities, however, mislead by insisting on perfect opposites. Only by the especially destructive standards of other revolutions was the American more restrained. During the Revolutionary War, Americans killed one another over politics and massacred Indians, who returned the bloody favors. Patriots also kept two-fifths of Americans enslaved, and thousands of those slaves escaped to help the British oppose the revolution. After the war, 60,000 dispossessed Loyalists became refugees. The dislocated proportion of the American population exceeded that of the French in their revolution. The American revolutionary turmoil also inflicted an economic decline that lasted for fifteen years in a crisis unmatched until the Great Depression of the 1930s. During the revolution, Americans suffered more upheaval than any other American generation, save that which experienced the Civil War of 1861 to 1865.

The conflict embroiled everyone, including women and children, rather than just soldiers in set-piece battles. A plundered farm was a more common experience than a glorious and victorious charge. Some historians treat the notorious wartime violence in the South as exceptional in an otherwise restrained war. This bracketing neglects the brutal war zones around British enclaves in New York and Philadelphia; the devastation of frontier settlements and native villages from New York to Georgia; and the Patriot repression of disaffection in much of New Jersey, Delaware, and the eastern shore of Maryland and Virginia. The true exceptions were the few pockets bypassed by war’s brutality, primarily towns in New England. If the American Revolution was less devastating than some conflicts elsewhere, it still featured much cruelty, violence, and destruction.

In popular history books and films, a united and heroic American people rise up against unnatural foreign domination by Britons, cast as snooty villains. That story of irrepressible nationalism inverts cause and effect in the revolution. The colonists were reluctant nationalists, and the revolution began, rather than culminated, a long, slow, and incomplete process of creating an American identity and nation. During the mid-18th century, British America was developing closer cultural, economic, and political ties to Britain. In 1775, Benjamin Franklin recalled, “I never had heard in any Conversation from any Person drunk or sober, the least Expression of a Wish for a Separation, or Hint that such a Thing would be advantageous to America.” Rather than an inevitable ripening of difference, the revolution violently wrenched reluctant colonists into a new and uncertain future as an independent country.

By writing of the American Revolution as pitting “Americans” against the British, historians prematurely find a cohesive, national identity. If we equate Patriots with Americans, we recycle the canard that anyone who opposed the revolution was an alien at heart. We also read American nationalism backwards, obscuring the divisions and uncertainties of the revolutionary era. This book refers to the supporters of independence as Patriots and to the opponents as Loyalists, but many more people wavered in the middle, and all were Americans.

But that upheaval also generated political and cultural creativity. Indeed, the accomplishments of independence, union, and republican government seem all the more remarkable given the grim civil war at the heart of the revolution. The founders had formidable enemies, internal divisions, and their own doubts, fears, and contentions to overcome. If they fell short in producing equality and liberty for all, they established ideals worth striving for.

To sustain support among war-weary people, Patriot leaders had to make political concessions that promised greater respect and political power for common men. In “My Kinsman, Major Molineux,” Hawthorne defines the internal social meaning of revolution, when the Patriot gentleman assures Robin that he can get ahead without the colonial patronage of his kinsman. As an alternative to British-led hierarchy, the gentleman promises a new meritocracy that will reward shrewd young men for their abilities rather than their birth. To win their civil war, genteel Patriots had to build a cross-class coalition that appealed to thousands of common men and women—as Hawthorne noted. Without mass participation, Patriots could not sustain riots and boycotts against British taxes or the later war against British and Loyalist troops. Hawthorne conveys the appeal of the republican society promoted by the Patriots. It might not achieve more equal results, in the distribution of wealth and power, but it promised fairer competition. Whether we have fulfilled or defaulted on that promise is the essential question of American politics.

The harsh experiences of war shaped the legacies of the revolution. More than byproducts of war, civilian sufferings helped to define the new republican government. During the 1780s, nationalists pushed for a stronger federal government by appealing to people who remembered the bloody anarchy of the war. Dorothea Gamsby, a wartime refugee, remembered, “Dismay and terror, wailing and distraction impressed their picture on my memory, never to be effaced.”

Turmoil persisted after the formal peace treaty. During the 1780s, the United States remained roiled by internal conflicts, meddling by other empires, and resistance by native peoples. Few Americans felt confident that their union could hang together given the interplay of their internal divisions with external threats. Most citizens favored their home state and feared political power exercised by a distant, central government. Their suspicion undermined the initial confederacy of the states, generating a crisis that led to adoption of the Federal Constitution of 1787. Rather than reflecting confidence in American unity, the new constitutional order was a “peace pact” meant to manage dangerous distrust and potential conflicts between the states. Instead of resolving the union’s problems, the Federal Constitution postponed the day of reckoning until 1861, when the union plunged into a bigger civil war that nearly destroyed the nation. That later civil war erupted over western expansion: whether territorial growth would commit the nation to free labor or, instead, extend slave society and its political power.

The importance of the West to making America’s future emerged during the revolutionary generation, when that vast region began just beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Between 1754 and 1763, the British and their colonists conquered French Canada and claimed the West as far as the Mississippi River. Colonists expected to share in the imperial fruits of victory. Instead, the British government treated them as second-class subjects by imposing new taxes and trying to protect Indian lands from settler expansion. The British also made unexpected concessions to their new Francophone and Catholic subjects in Canada. British rulers treated their coastal colonists as just another subordinate group within a composite empire of diverse peoples managed from London. This new treatment dismayed colonists who had counted on their British culture and white skins to justify superior privileges. If denied dominion over natives and Francophones, the colonists worried that they would become dependents ruled by Britain. They called this anticipated fate “slavery,” an anxiety fueled by the growing population of the enslaved among them.

In the trans-Appalachian West, the British Empire displayed a fatal combination: threatening pretensions without sufficient power to enforce them. Defying British troops, settlers continued to flow west to take Indian lands. The British failure in the West discredited imperial rulers at the same time that they tried to impose new taxes on coastal colonists. Most interpretations of the revolution’s causes subordinate western issues, treating them as minor irritants less significant than the clash over taxes. American Revolutions balances the scales by linking western conflict with resistance to parliamentary taxes as equal halves of a constitutional crisis that disrupted the British Empire in North America.

Essential to understanding the causes of the revolution, the West proved even more important to its consequences. After the war, thousands of settlers moved across the mountains to make more farms and towns. That growth would define, for better or worse, the new nation’s prospects. During the 1780s and early 1790s, the exodus compounded the fissures within American society and threatened to dissolve the weak confederation of the states. Newcomers settled along vast river systems that drew their trade either north to British Canada or south to Spanish-held Louisiana. American leaders needed to overcome that geography to win western allegiance. If they could succeed, the growing settler population would become the nation’s greatest asset rather than its chief liability. Westerners might form a national constituency stronger that anything in the East, where state loyalties dominated.

To prevail in the West, Patriots had to learn lessons from the British failure there. Thomas Jefferson noted that frontier folk “will settle the lands in spite of every body,” including any government, American or British. Unable to restrain settlers, American leaders needed to help them. By leading, rather than slowing, the process of Indian dispossession, the federal government could gain influence in the West. Jefferson promised equal rights for common white men and promoted their prosperity through westward expansion. After much trial and error, and close calls with collapse, an American union would succeed where the British had failed by sustaining an “empire of liberty” beyond the Appalachians. But that new empire came at the expense of Indians who lost their homelands.

By emphasizing the broader North America, including the West, this book breaks with an older view of colonial America as limited to the Atlantic coast and almost entirely British in culture. By adopting “Atlantic” or “Continental” approaches, recent historians have broadened the geographic stage and diversified the human cast of colonial America. New scholarship pays more attention to rival Spanish, French, Dutch, and even Russian colonizers. We also now understand that relations with native peoples were pivotal in shaping every colonial region and in framing the competition of rival empires. Enslaved Africans also now appear as central, rather than peripheral, to building colonies that overtly celebrated liberty.

Most books on the revolution and early republic, however, still focus on the national story of the United States, particularly the political development of republican institutions. That approach demotes neighboring empires and native peoples to bit players and minor obstacles to inevitable American expansion. Canada, Spanish America, and the West Indies virtually vanish when American historians turn to the period after 1783.

American Revolutions offers a sequel to my earlier book, American Colonies, which presented a continental history of colonial experiences. Drawing attention to multiple, competing empires, that book avoided a singular focus on British America. American Revolutions similarly emphasizes the multiple and clashing visions of revolution pursued by the diverse American peoples of the continent. It differs from books which suggest a singular purpose and vision to the conflict and its legacy. The revolutionary upheavals spawned new tensions and contradictions rather than neat resolutions.

American Revolutions situates the creation of the United States in the continental and global dynamics of the rival Spanish, British, and French empires and the many natives who still held most of North America. Although shorn of thirteen colonies by the revolution, the British Empire retained Canada and parts of the West Indies and gained ground in India. In Canada, Britons redesigned their colonies to avoid an American-style revolution. In Latin America, the war initially seemed to revitalize the Spanish Empire but ultimately increased tensions between colonial elites and imperial authorities. In the next generation, those tensions would create republican revolutions throughout Spanish America. Beyond the Appalachian Mountains, native nations created confederations to halt expansion by American settlers. Further west, on the Great Plains, some Indian peoples gained power over others by deploying guns and horses to control immense herds of bison.

The founders of the American union understood that they were enmeshed in global networks of trade, culture, diplomacy, and war. As they expected, their actions affected, and were affected by, the rest of the world. In 1818, John Adams noted, “The American Revolution was not a common event. Its Effects and Consequences have already been Awful over a great Part of the globe. And when and Where are they to cease?” Indeed, those consequences have not yet ceased.

The politics of the early republic remained entangled with those of the broader world. By helping the Patriots win independence, the French reaped national debts and republican ideas that led to their own revolution in 1789. During the 1790s, the American political parties polarized as Republicans embraced the new revolution, while Federalists denounced its radical turn. In 1791, the French Revolution inspired a massive slave revolt in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue, which led to the creation of a new nation, Haiti. When black people became revolutionaries, white Americans recoiled. They set new, racial limits to the spread of republicanism, retreating from the implicitly universal promises of their revolution. But the American Revolution generated many conflicting meanings, and some Americans kept alive an alternative, broader vision of revolution that might lead to a “new birth of freedom” in a later generation.