A noted historian recalls how he came to learn about the five-star general who led American forces to victory in World War I, and the sacrifices made by his family.

-

Fall 2018 - World War I Special Issue

Volume63Issue3

Editor's Note: This essay, the last that Gene Smith wrote for American Heritage, was in our files when the historian passed away in 2012. Gene was a long-time favorite of our editors, having published 31 essays in the magazine over the years.

Gene once wrote about himself in the third person,"If there was an afterlife...he'd love it for the opportunities offered to interview people he studied in life.” We hope that Gene has had a brandy somewhere with Black Jack.

No matter how often he called, I still always jumped.

“Hi, it’s Jack Pershing.”

Who? What? Black Jack of the First World War wants to talk to me?

But, of course, it wasn’t the general on the phone. He died in 1948. This was his grandson, Colonel of the Reserves John Warren Pershing, born 1941. He was of great importance to a book I was doing on the general’s life that was eventually to include the stories of his son and grandsons. The general’s forbears had served in Colonial armies even before the Revolution, later in abolitionist-slaveholder skirmishes and then in the Civil War. He himself participated in the last Indian campaigns, Cuba, the Philippines, chasing Pancho Villa in Mexico, then the Great War. His son saw action in World War II. Then the grandsons in Vietnam. It was the two-hundred-year cycle of a family’s military history. I needed Colonel Pershing to tell me about the most recent times.

I was fearful about getting in touch with the colonel, worried that he’d tell me he wasn’t interested. Col. Pershing was a wealthy man, and knowing that the rich are not always forthcoming nor anxious for publicity of any kind. It took a long time before I nerved myself up to call the nearest of his five residences. When I got an answering machine I always hung up. I must have made twenty calls. Finally, I left a message.

Two days later: “Hi, it’s Jack Pershing.” I told him of my research, including six months of going through his grandfather’s papers in the Library of Congress. The general had saved everything. Many career officers, subject to frequent changes of station, throw things out rather than pay for shipment, but John J. Pershing kept letters sent and received to the folks back home when he was a second lieutenant chasing Geronimo out west, kept love letters to and from his wife, bills from hotels when a military observer during the Russo-Japanese War, letters to old West Point pals and relatives from along the border during the Mexican troubles, and France in 1917-1919 and during his stint as Chief of Staff and on into retirement.

Col. John Warren Pershing, Jack, listened less than he talked. He sounded vibrant, alive, profane—jazzy. I rather dazedly laughed when he told me a risqué joke. This was, after all, the grandson and namesake of the fearsomely stern general of the armies of the United States with six stars which although seen on a stamp brought out after his death, he never actually wore in life. (Ike, MacArthur, et.al., each a mere general of the army, only had five.)

Jack suggested I come to his New York City pied-a-terre so that we could go to lunch. When I showed up he showed me a magnificent nine-foot grandfather’s clock which an expert had just determined was doctored up to make it look more valuable than it was. The doctoring up had taken place an estimated two hundred years ago. “Had crooks even in those days,” Colonel Pershing remarked. He asked if I wanted a drink. He got a glass and ice and showed me the liquor cabinet, I asked if he wasn’t going to join me, and he said he was a recovering alcoholic. I said that in that case I didn’t want to drink in front of him, and he told me not to worry. In later visits to his Locust Valley, N.Y., home, and his Rhode island place, he was the same. He even kept bottles for guests on his boat.

His apartment had a distinctly military touch, with pictures of himself and others in uniform, and a cabinet containing figurines of soldiers through the ages and one anatomically correct, early World War II British statuette of a very scantily clad French can-can girl. On the little pedestal was inscribed, “What We’re Fighting For.”

His grandfather wasn’t nearly as earthy, although in his voluminous Library of Congress files there’s an exchange of letters from the 1930s in which an old school chum writes addressing the general as “Dear John”—for only a tiny percentage of people ever called him “Jack”—and enclosing a photocopied letter John had written the friend when on vacation from Northeast Missouri State Teachers College in the early 1880s, in which John uses mild profanity to describe the pen he’s using and “bum paper.” The general wrote back that it was good to hear from his old friend, but could he keep the letter private?

John J. Pershing departed the Missouri school for the United States Military Academy solely because West Point offered a free education. “But John, you’re not going into the army, are you?” his mother asked. He never really intended to; his plan was to graduate, serve the required four-year tour, and go on to be a lawyer. But at The Point he would become, as with Robert E. Lee before and Douglas MacArthur after, First Captain of the Corps of Cadets, and a natural leader and soldier.

Out on the western frontier Pershing commanded Indian scouts patrolling Wounded Knee after the 1890 massacre there. He sympathized with the Indians and wrote home their treatment was a disgrace. He went on to command troops of the black Tenth Cavalry, from which in a manner as fraudulent as his grandson’s clock came his nickname of “Black Jack.” It was never that in the Old Army: there he was “Nigger Jack.” The papers made up the sanitized version when he became famous.

In 1899, after Cuban fighting which found him and his black soldiers saving Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders from probable annihilation, Pershing went to the Philippines and to Mindanao, an island largely inhabited by savage followers of Islam—Moros. The Spanish spent 300 years unsuccessfully trying to discipline them. (So formidable was a charging Moro that the regulation U.S. Army .38 was found inadequate to stop him, and the .45 introduced.) Seemingly alone of Americans in Mindanao, Pershing came to understand a people whose culture came from the dawn of civilization, industriously studying their language, manners, ways. Appointed to command of an outlying post in the heart of Moro country, he worked to make friends. Squatting on his heels in native fashion, he held hours-long conversations and went to villages to eat exotic delicacies and decline presentation of harem members when he spent the night.

Promoted captain after fifteen years’ service, he so captivated the Moros—”those we serve down here”—that they consecrated him a datto, a priest.

Such a thing had never been dreamed of before. Women asked him to be honorary father to their children, and sultans, panditas, mandarins and maharajahs came to him for advice. Stateside papers depicted him as a god bowed down to by half-naked natives.

When one powerful Moro group defied American rule in most violent fashion, Pershing led an expedition to, as he put it, “wage peace.” He took the field at the head of a column of infantry, cavalry, artillery, hospital corps, signal men, with pack train of hundreds of animals. A junior captain, he was commanding an all-branches expedition of almost brigade size. He reduced the forts of the insurgents with minimum loss of life and in America was compared to Cortez, but with superior motives. He returned home and was mentioned in an address to Congress by President Theodore Roosevelt. Promotion in the army solely on the basis of time served in a lower grade was wrong, Roosevelt said. It ought to be possible to promote officers for outstanding performance, a prime example being Captain Pershing.

The listeners to the December 7, 1903 speech included Miss Helen Frances Warren, daughter of Wyoming’s Senator Francis Warren, the richest citizen of his state and a sheep rancher once called on the Senate floor “the greatest shepherd since Abraham.” She was 23, a recent Wellesley graduate, no great beauty but possessing a lovely smile and great laugh, someone considered very likeable, kind, modest, friendly. On December 9th she wrote in her diary of a dinner party she had attended. “Met Mr. Pershing, of Moro and Presidential message fame.”

They met again at dinner on the 11th. “It was just great. Have lost my heart,” Helen wrote. The next day, after a dance at the Washington Navy Yard: “Have lost my heart to Captain Pershing irretrievably.” The feeling was mutual. Pershing called on an old friend sound asleep and woke him up to say, “I’ve met the girl God made for me!” But he was very worried, he added. She was rich while he had nothing but his army pay. They had known one another less than a week.

In the years that were to come Jack and Helen wrote or telegraphed every day they were apart, sometimes twice a day. No message, none of the hundreds and hundreds in the Library of Congress, failed to mention the great love each felt for the other. But for the moment there remained the issue of their financial disparity, her income from Wyoming rental properties five or six times his annual salary, and her eventual inheritance. “Let me tell you right here,” she wrote, “that you might just as well stand in the middle of a field and wave a red flag at a bull as to flaunt that word ‘obstacle’ at me. Here I am just urging and urging you to marry me, and I am getting discouraged. I am going to bend all my efforts to fall in love with every attractive man I meet. Please may I kiss your nose?”

He asked her father for her hand. The wedding was the social event of Washington’s 1904 season, with President Roosevelt at the church and his daughter sitting with the bridal couple at the reception. The honeymoon was by liner to Tokyo and his departure from there as military observer with the Japanese running rings around the Russians in Korea. and Manchuria. The first of their four children, Helen, was born in Japan. Twelve days later, on September 20, 1906, came news that Captain Pershing by Presidential fiat had been made Brigadier General Pershing. Tired of waiting for Congress to act on his promotion-by-merit concepts, Roosevelt had jumped Pershing over 257 captains who were senior to him, 364 majors, 131 lieutenant colonels, and 110 colonels.

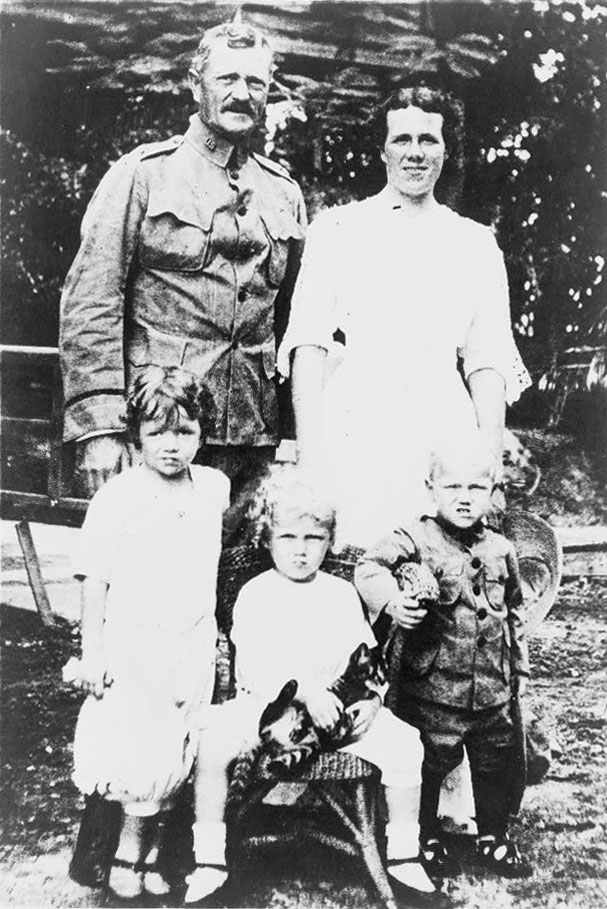

They went to the Philippines and his assignment as civil governor and military commander of his old stamping grounds, Mindanao, and lived a pasha-like existence in an official residence like a servants-and-aides-galore palace facing the Straits of Basilan and equipped with a dining room seating sixty, and verandas filled with palms and hung with orchids. Another daughter was born, Anne, and then a son, Francis Warren for his grandfather, and another girl, Mary Margaret, named by her two older sisters. When rebellious tribesmen holed up in a mountaintop fort, sallying forth to kill farmers and villagers, Pershing attacked with utmost self-imposed limitations. Predecessors of his had howitzered down not only emplaced warriors but also their women and children; he would not have such a thing on his conscience for the fame of Napoleon, he told his wife. (His longtime associate General Robert Lee Bullard once wrote that at heart Pershing was “a pacifist.”)

Father and mother—always “Frankie” or “Frank” to those who knew her—returned with the four children to the United States in January of 1914, where the general assumed command of the Eighth Brigade in California’s Presidio. They were enchanted by San Francisco’s cool weather after years in the tropics, and trips to Yosemite Valley and preparations for the coming Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915, a great world’s fair. When the general’s lady suffered serious injuries from an automobile hitting her horse-drawn little coupe, she made light of them by writing her father and stepmother that “though I have Heinz’s 57 varieties of cuts and bruises,” she also had a hospital room filled with wonderful bouquets people sent, plus books, notes and telegrams. Everyone was so nice to her that “I am afraid I shall acquire a habit of being run into or away with. The advantages seem to outweigh the discomforts.” She signed as “Your affectionate rubber ball.” The laughing lady, Pershing’s younger brother Jim always called Frankie.

Soon after she got out of the hospital, her husband and his Eighth Brigade were ordered to Fort Bliss at El Paso. The situation after the fall of Porfirio Diaz, Mexico’s iron-fisted ruler of more than a quarter century, saw caudillo, assassin, generalissimo, insurgent, outlaw, private army and armed band warring upon one another in lawless chaos as Americans north of the border blocked windows with mattresses to protect against bullets flying across the Rio Grande. The possibility of United States intervention was under consideration.

Brigadier General Pershing hated being away from his family, and they from him. But all arrangements were temporary along the border and so it seemed best if they did not join him at Fort Bliss. The usual husband-wife letters went back and forth, joined now by those of the two older children: Dear Papa, I am sending Virginia a easter basket are you going to send any easter eggs. I am to give people easter eggs are you. We dyed some eggs to give to Virginia and Dorothy. We will have a nice time on easter will you. We will. I do not know anything else to say. Your loving daughter Helen. Dear Papa, I love you. Baby, Warren and Helen are having a nice time. This is all I can say. From Anne. To Papa. The end.

What President Wilson termed “watchful waiting” dragged on and finally, in the summer of 1915, the Pershings decided to unite at Fort Bliss. First Frankie wanted to attend a San Francisco get-together of West Coast Wellesley College alumnae. It would be held on August 25th. She and the children would entrain for Texas on the 28th to end the family’s fourteen-month separation interrupted only when on rare occasions the general could depart his command. On one visit he had supervised the varnishing of their Presidio house’s floors.

After the Wellesley affair, wife told husband all about it in a late-night letter ending, “Goodnight, dear heart. Your Frankie.” They would be together in three days at Fort Bliss.

The next night, August 26, 1915, she had as guests her Wellesley roommate Anne Orr Boswell and the latter’s two children, and another woman who had known Frankie’s mother back in Wyoming. It was a chilly and foggy evening. The children upstairs in bed, the three women sat up late around the downstairs living room’s coal fire. They went to their rooms around midnight.

Several hours later the telephone rang in Brigadier General Pershing’s Fort Bliss headquarters. The caller was an Associated Press correspondent in El Paso. He thought he recognized the voice on the other end of the phone as one of the general’s aides.

“Lieutenant Collins, I have some more news on the Presidio fire.”

“What fire?”

The correspondent realized that he was not talking to Lieutenant James L. Collins. “What fire?” the voice on the phone repeated. The recognized whose it was. He stumblingly said he would read a dispatch that had come over the teletype. He did so.

“Oh, God!” Pershing cried. “My God!”

A coal from the living room fireplace had slipped out onto the floor whose varnishing the general had supervised. Around two in the morning Frankie’s Wellesley roommate Anne Orr Boswell briefly awoke and saw light coming from the crack beneath her closed door. Frankie must have turned on a lamp, she thought. Mrs. Boswell dozed off, woke up again. The light seemed more intense. She opened her door. A great gust of smoke and terrible flashes of flame came at her. She screamed, “Frank! Frank!” at the door on the other side of the hall. It would be impossible to cross over to it. The foot of the stairs leading down to the first floor, she saw, resembled a furnace—a great roaring mass of flame. She rushed to her children, got them up, stood with them on a porch roof, cinders pouring down on their heads, threw them down to the outstretched hands of soldiers who had come running when the post signal gun went off, and then leaped herself to lie supine in her nightgown. The other guest jumped from a separate room into the arms of a soldier. In the smoke and fog and steam rising when hoses were turned on the flames, people mistook Anne Orr Boswell’s two boys for the Pershing children.

Then it was realized they were not. There was a rush to get into the house. Men groped through smoke to be driven back by overwhelming heat and fire, tried again and came out bearing burdens. Frankie had just turned thirty-five years of age. Helen was eight. Anne was seven. Mary Margaret was three. There was not a mark on any of them. They had died of smoke asphyxiation. The son, Warren, lived because he was sleeping in a room whose door was closed.

On a train heading west with Lieutenant Collins, General Pershing screamed and cried. At Bakersfield a friend came into the general’s stateroom. “I can understand the loss of one member of the family, but not nearly all,” Pershing gasped. He put his arms around his friend’s neck and held him so, constantly weeping, as the train made for Oakland. They crossed the bay to San Francisco and an undertaker’s establishment where he sank to his knees before the first casket, stayed so for some ten minutes, and did so for an equal time before the next, and the next, and the next. Three of the coffins were so pitifully small.

He returned to Fort Bliss with Warren, his spinster sister May coming along. Pershing was about to turn fifty-five; the marriage had lasted ten years. Endlessly he blamed himself for applying the flammable varnish; it seemed for a time all he talked about. Work seemed his only salvation, and grimly attentive to all details, a withdrawn schoolmaster in uniform drilling his men while to the south Mexico boiled.

One of the officers at Fort Bliss had a sister who came for a visit. The officer was Lieutenant George S. Patton, Jr.; the sister was Anne—always called “Nita.” Pershing spent time with her and went on leave to the Patton place in California. When he returned to duty, her letters seemed to indicate a certain, shall we say, particularly close relationship, with much mention of late-night kisses and embraces. I discussed this with the grandson of the future World War II hero, Nita’s grandnephew. “In our day,” I told Robert Patton, “there would be no doubt about what she alluded to. But in 1916? Did they or didn’t they?”

“I’ve often wondered,” Patton replied. “We decided that we didn’t know. In time Pershing asked Nita Patton to marry him. She said she would. By then it had been decided that the best thing for Warren was that he go to live with Aunt May and another aunt, the widowed Elizabeth Pershing Butler, in the house the sisters shared in Lincoln, Nebraska. There he celebrated his seventh birthday with new friends from his new school, Aunt May writing the general how lovely Warren’s comportment was as he served cake to everyone before taking a slice himself. When given the bicycle the general ordered as his present, “0, he just jumped up and danced. I never saw a child so delighted.” Already mother and sisters were fading from memory. The boy wrote: “I thank you very much. I had a nice Party with 25 children. A kiss. Papa I love you. Warren Pershing.”

Not then, nor when he was grown, did Warren ever hear from his father a single reference to the events of the early morning hours at the Presidio on August 27, 1915.

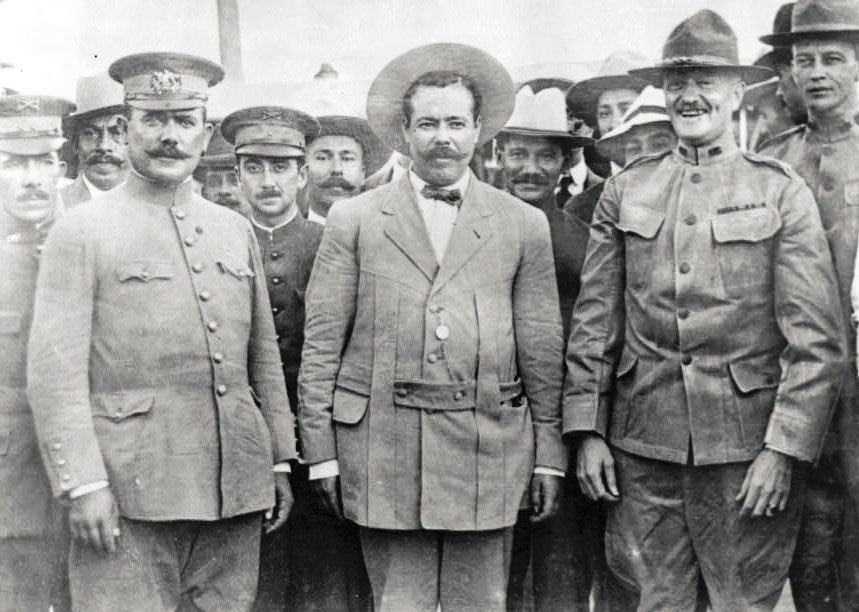

In March of 1916 Francisco (Pancho) Villa, in equal parts bandit, desperado, Robin Hood, rampaged across the border and into Columbus, N.M., shooting and burning. Pershing was ordered to go south and do something. He launched into Mexico at the head of 12,000 men. Under Chihuahua’s brutal desert sun and on its icy high mountains he sought Pancho Villa, tireless, demanding, sleeping on the ground and bathing in alkaline water holes and living off primitive rations while he deployed aircraft, motor transport, advanced signal equipment, things never seen before in field operations anywhere. He performed strung-out marching over a line of supply and communications longer than Sherman’s in the March to the Sea, and with less illness, malingering, crime, than had been dreamed of in the Civil and Spanish-American Wars. His was a brilliant little army, rigidly disciplined, its leader, the accompanying newspapermen said, attuned to every detail, a commander knowing by name every hired scout, how many horses were hit in the lightning story, all the nosebag gossip of the picket line and every latrine rumor.

He made major general, but when a West Point classmate wrote congratulations, sadly replied, “All the promotion in the world would make no difference now.” Nita Patton did not see it that way: “Dear Major General Pershing: Do you feel horribly dignified now, or can you still smile occasionally?” He and his troops crossed back north over the border, Pancho never caught but his band broken up, with two of his underlings personally shot with a pistol by Nita’s brother George and brought back to headquarters slung across the fenders of a touring car like deer after a hunt.

President Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, and Pershing was ordered to France. In time a vast army would follow. In Paris he was welcomed as the deliverer of the Old World come across the seas from the New. He built up his incoming forces. When he left New York harbor, his aide James L. Collins had expected it would be accompanied by an announcement of his engagement to Nita Patton, but there was none, and shortly after arrival he met a Frenchwoman, Micheline Resco.

Going through the daily diary kept by the general’s staff during the First World War, now in the Library of Congress, I was struck by how many nights he was depicted as “studying French.” Eventually I found that the seminars were conducted in Mlle. Resco’s apartment. At 23 when they began their affair, she seemed more the likely sweetheart of a corporal or lieutenant than of the 57-year-old commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Forces, but their relationship lasted until the day of his death. In time a bitter Nita Patton would tell her family that John J. Pershing was “a little tin god on wheels.” She never married.

History has held Pershing’s foremost contribution to the winning of the Great War was that he never acceded to the demands of the French and British that he feed his men into their forces. He did not fight his troops even when Prime Minister David Lloyd George formally requested Secretary of War Newton D. Baker to relieve him of his command, but built up his staff and supply systems until he struck with murderous force. It was universally expected that the war would not end until there was a campaign of 1919, but Pershing finished the fighting in November of 1918. He and he alone of all the Allied chiefs was against acceptance of the German request for an armistice, saying he did not want to let the enemy down easy, but rather to treat them as Grant treated Lee at Appomattox, all arms and battle flags ceremoniously to be laid down. Then a victory march on the Unter den Linden in Berlin. He was overruled.

Almost immediately the Germans promulgated the myth that they had never really been defeated, and repeating that over and over an ex-lance corporal of Bavarian infantry parlayed it into supreme power. In later years Presidents Roosevelt and Truman wrote Pershing of how right he had been in 1918.

All through the war he kept up correspondence with Warren back in Nebraska, hearing from the boy of his schoolwork and musical and theatrical activities, and the fireworks Aunts May and Elizabeth bought him for the Fourth of July. The general wrote back about horseback rides along French rivers, and of how much he thought about Warren and how much he missed him. Pershing in those years never but once is recorded as mentioning his dead wife and daughters to anyone, even old friends who had known them. The sole exception came when during the Meuse-Argonne fighting he rode with an aide in the rear of his six-wheel Locomobile limousine. His losses were greater than the entire strength commanded by Lee for the South and Meade for the North at Gettysburg, with mule carts bringing back behind American lines heaped soldiers. “Frankie, Frankie,” Pershing cried, burying his face in his hands, “My God, sometimes I don’t know how I can go on.”

The fighting done, he had Warren sent over. Standing on the deck of Leviathan, the nine-year-old breezily addressed Secretary of War Newton Baker as “Chief,” and let a crumpled fifty-dollar bill fall from his pocket. Once his father asserted control of him, there would be no more of that. Pershing’s greatest fear was that his son would show poor manners, or be spoiled by knowledge of the money that was his through his mother’s inheritance. A small figure in blue Buster Brown suit and blue cap in a sea of khaki until he was given a miniature doughboy uniform with three stripes on the sleeves—from then on he was addressed as “Sergeant”—he was with his father at inspections, sporting events, plays, concerts, dinners, balls, parades, and with field marshals and the king and queen of England and of the Belgians. Micheline Resco took him around Paris. Pershing spent a part of each day with Warren. “I like to be with my boy,” he said. “I want to see all of him I can. I wouldn’t feel right if I let the evening pass without spending part of it with my son, even if he is asleep.”

When the great American army was demobilized, father and son went home. The school year of 1919-20 was about to begin, and so Warren returned to Nebraska and his aunts. Summers from then on he spent with his father on inspection tours, at American Legion conventions, and hunting, fishing and sailing. Letters to his son from Pershing were filled with dubious health advice and warnings about taking care when riding his bike or handling golf clubs which could result in injury, plus injunctions regarding sloppy handwriting. Always the rigid disciplinarian, the career officer, the general never failed to rescind an order as soon as he issued one to his son. This went on for years. When Warren was in college his father, enraged that the student had failed to write someone a thank-you note, threatened to cancel a projected European trip—and then sent him across the Atlantic with a new LaSalle convertible, a junior Cadillac.

Warren Pershing became tall, blond, good-looking, very likeable. Like many bright boys, he did not do well in the classroom. His dismayed father removed him from Exeter and shipped him off to a strict boarding school in Switzerland, where he performed adequately. The same was true of his four years at Yale. As soon as mid-term or final grades came out, his father must immediately be informed of results—often by cablegram to Paris, where Pershing spent a part of each year overseeing construction of American Expeditionary Forces cemeteries and spending time with Micheline Resco and his dearest European friend, Marshal of France Henri Philippe Petain.

Petain had saved France in 1917, and for that, Pershing esteemed him, and also for the marshal’s dry wit. Petain was France’s greatest soldier, Pershing felt. He had never liked Marshal Foch.

At Yale his son spent money too freely, the general opined in almost every letter, immediately then sending more. After graduation Warren went into the brokerage business using a portion of his inheritance to set up a firm destined to become a substantial presence in financial circles. “Very striking,” Pershing’s longtime aide George C. Marshall, Jr., wrote upon receiving an announcement card, “in the name, number, street and city—Pershing, No. 1 Wall Street, New York.”

The general by mandate retired from the army at 64, in 1924.

He then spent almost ten years writing his memoirs of the war. They were dry, cold, like an after-action report, of no interest to anyone but military specialists. I myself have never read them—I read at them. Pershing knew how bad they were, and set out to write a more personalized autobiographical work. His dozen drafts had great details—I used many in my book—but the tone was fatally impersonal and detached. The work was never published.

The young man about town Warren Pershing became frequently mentioned in the New York papers, his name soon coupled with that of Miss Muriel B. Richards, described in Society sections as “eye-compelling, one of the more attractive members of our fashionable younger set,” her picture often published when seen on Bermuda stays or taking “an active part in the social whirl in town, down at Palm Beach, and over in London and Paris.” She was a great heiress, the “B” in her name standing for Bache as in the towering financier Jules S. Bache, her grandfather. She had been brought up in his Fifth Avenue mansion more like a palace than a town house, with on the walls works by Rembrandt, Titian, Raphael, Durer, Holbein, Gainsborough, Fragonard, Velazquez, Fra Filippo Lippi and Filippino Lippi, Goya, Van Dyck, Frans Hals, Vermeer, Watteau, Romney and Sir Joseph Reynolds, and at the Florida place and camp in the Adirondacks of thousands of acres.

The couple married in 1938. It became the principal of F. Warren Pershing & Company’s ambition to have one day annual earnings equal to what came to his wife through the income on her inheritance. That took him twenty years. They had two children, John Warren and Richard Warren. The boys’ grandfather was by the time of their births in declining health and often in Walter Reed Hospital in Washington. He eventually settled in there full-time, with his spinster sister May living on the grounds.

Within two months of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, nearly ever paper in the country carried the story that Warren Pershing had enlisted in the army as a buck private. Warren certainly didn’t have to do that—he was, after all, 33 years old, educated, and officer material. He proved a splendid private of the Engineers, put in for a commission and got one. Parental influence was never utilized until, after two years of Stateside duty, Warren asked his father to see if he couldn’t get overseas.

George Marshall was applied to and Warren was shipped to England and then Normandy right after D-Day and then as a combat engineer all across France and into Germany. His letters to the general and Aunt May in Washington read very well today, sparkling, alive, funny, filled with the kind of touches and details that eluded the general when he wrote of his life in the published and unpublished books. Warren rarely spoke of the experiences that earned him five battle stars, but could be very moving when he wrote of revisiting places he had seen with his father when he was a child, right after the First World War.

Discharged as a major, he returned to the Upper East Side life of the rich, living with Muriel and the boys in a magnificent Park Avenue duplex, spending time at the place in Jamaica and the camp in Canada and seaside mansion in Southampton. Warren and Muriel moved in New York’s most elite social circles. They drank, as people of their type did in those days. It was the servants who essentially raised Jackie and Dickie.

Sometimes the family went down to Walter Reed to see the general and Aunt May, and Micheline Resco, whom Pershing had gotten out of France when the Germans came in 1940, and installed in Washington’s Shoreham Hotel. He was always thrilled to see everybody, to play soldiers with Jackie, who beat him by sweeping the troops of the general of the armies of the United States off the board with his arm. But increasingly Pershing was falling into the mental lapses of a very old man. Sometimes he was confused for as long as ten days. The tendency had begun to show itself as early as 1942. When George Patton came to call on the day he was shipping out to North Africa, Pershing did not know him. Then he came to himself and they talked about days in Mexico and France. At the end Patton sank to his knees and kissed his old commander’s hand. Then he rose and put on his hat and saluted, and when Pershing returned the honor it seemed to Patton for the moment at least if twenty-five years had fallen away.

The general of the armies died in 1948, just short of 88 years of age. Nearly half the District of Columbia’s population turned out to watch the mile-long glittering funeral procession led by President Truman and Generals Eisenhower and Bradley to Arlington and a rise thereafter called Pershing Hill, where the grave was surrounded by great trees.

Years later, seeing on television President Kennedy’s similar funeral, Jack and Dick Pershing asked their mother why they hadn’t been down for the general’s. She replied she had felt they were too young at the time for that sort of thing. it was very much Muriel’s imperious manner of deciding things. She was regal in her ways, acting, her sons’ friends thought, almost in the manner of a reigning queen. Warren the friends found handsome, impressive, aloof, distant. Jack and Dick privately called him Onion, for no matter how many layers you peeled off, there were always more. As teenagers they were sent off to the strict Swiss school to which the general had sent their father. Dick was joining in to haze a Jewish boy there when another student told him his own ancestry wasn’t so pristine – the student’s mother had said so. The young Pershings telephoned New York – no easy matter in the 1950s – and for the first time learned that Jules S. Bache had been Jewish. Theirs was not the only Social Register family preferring not to discuss such matters.

Once mother and father came over to visit and tour with the boys. For half an hour Warren stood silently staring at the Rhine River point where under German fire he had worked to put up temporary crossing bridges, at some cost to many of his fellows. “Don’t bug him, leave him alone,” his wife told their sons. In Paris they visited the aging woman who had devoted her life to John J. Pershing, was living now on money he left her supplemented by donations from Warren, and by his instructions was to be called “Aunt Micheline” by his sons.

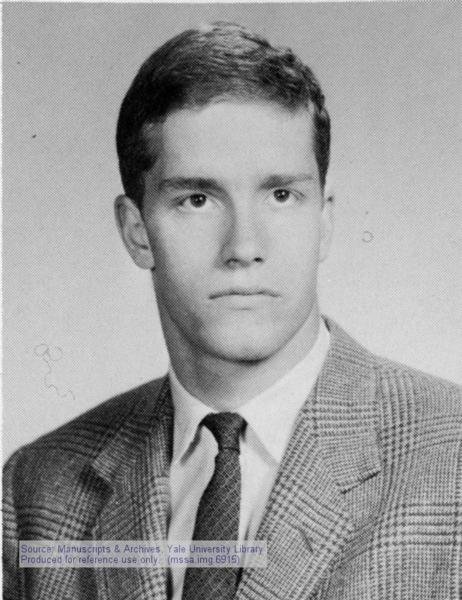

After a couple of years in Switzerland the boys came back to American prep schools, where Dick proved a better student than Jack. Dick was maddeningly talented. He was great at soccer and his ability at lacrosse was such that he could have performed at a national level if he’d applied himself; he was a terrific singer and musician, good artist, top student though he hardly studied, quick, verbal. His foremost capability was in being funny. He made people cry with laughter, a tremendous clown and mimic, great with Germanic-sounding doubletalk gibberish recitations. Jack went to Boston University, Dick to Yale.

After college Jack joined the army. He’d been a big wheel in the Boston University unit of the elite Pershing Rifles, the military honor society in its heyday right before Vietnam and the protests, and in the Reserve Officers Training Corps, where at a ceremony he commanded two thousand cadets. Jack loved army life, did great in Special Forces, was stationed in Europe as the third Pershing who could say that.

At Yale Dick was a notable hell-raising and harum-scarum type spending sums of money which made his classmates gasp, involved in stunts and debutante-chasing and getting through exams only by virtue of last-minute study sessions. “I guess I better get the book,” he remarked to his roommate the day before the end-of-semester Russian History exam, bought one, sat up all night, passed. He was tapped for Skull and Bones. Both boys in college years often had friends into their family’s Park Avenue duplex. There was a particular divan in a first floor drawing room with over it a large oil painting of the general of the armies, in uniform. The divan was the only point in the room that his eyes could not reach, and upon it occurred activities not so remarkable for college boys and their young lady friends. “I’ve had that re-covered twice, and I don’t want to do it again,” the Grand Dragon – so her sons called Muriel – finally declaimed.

There wasn’t anything very pressing for Dick to do upon graduation in 1966, so like brother Jack he joined the army. It made sense to his fellow Yalies off to grad school, fellowships, study abroad – for Dick, after all, was a Pershing. He became engaged to Miss Shirley Hildreth of Southampton, whose appearance was such that people compared her to the movie star Ali MacGraw. He put in for OCS Georgia’s Fort Benning, did splendidly, and became a second lieutenant of the 101st Airborne in the spring of 1967, Jack flying over from Germany to swear him in, a right available to anyone holding a commission. Eighty-one years had elapsed since their grandfather attained that rank. In December of 1967, Dick’s brigade got orders for Vietnam. It was just in time for the Tet Offensive.

There was a fellow at Yale with Dick who had a brother who ran into Dick near Hue, the old imperial capital, in early 1968. He told me Dick was completely unrecognizable from the rich and carefree playboy he’d been back in New Haven, but was resolved, involved, focussed, very, very disciplined. He was just back from a mission when the friend’s brother talked with him – had lost a lot of his platoon, lots of casualties. Now he had to arrange the tagging and bagging of the dead, the securing of their personal property for sending home, and the letters to the next of kin. Dick had a steely-eyed look of determination and projected a very clear and strong sense of duty, the friend’s brother told me; he took away from their meeting that Dick was going to get this thing done, play the cards he’d been dealt. A few days later Dick was on a search-and-destroy mission when his platoon ran into a North Vietnamese Army unit. His people were badly cut up. A soldier was down in open space. Dick went to drag him to safety.

The following morning, a Sunday, Jack, back from Germany, was awakened early in the Pershing apartment by a maid who said a uniformed army colonel wished to see him. The reason that a would call on a captain before nine o’clock on a Sunday morning immediately suggested itself to Jack. Any faint hopes he had about being mistaken vanished when he saw the colonel’s face. Dick was awarded posthumous Bronze and Silver Stars. Interment was at Arlington on Pershing Hill, next to the general, the army’s lowest-ranking officer, second lieutenant, lying by its highest, general of the armies. Jack afterwards took the broken Shirley Hildreth along with him on dates, or out for a movie and a bite. In time it came to him that he loved her. She felt the same way about him, and in the fashion of Leviticus’s biblical injunction, Jack married his dead brother’s girl. I found her in a lengthy interview to be quick, clever, perceptive.

Jack left the army and joined F. Warren Pershing & Company as a floor broker, work he loved. Muriel died, and Warren followed. They were cremated. Jack’s inheritances involved what Warren had from his dead mother’s money from her father, Wyoming’s richest citizen, Warren’s own from his prominent Wall Street firm, Muriel’s from Jules S. Bache, and the general’s leaving, minor compared to the others, a few hundred thousand. Jack was, as earlier indicated, a very rich man, but I never found him snooty in the slightest. He was what used to be called a clubman and sportsman, maintaining a pack of hunting dogs and journeying to grouse shooting in Scotland and fishing in Iceland. He was tremendously active in the army reserves, going off on missions for Chiefs of Staff William C. Westmoreland, whom he addressed as “Westy,” and Gordon Sullivan, “Sully” to him. On the 75th anniversary of the landing of the doughboys in France, Jack went as special representative of the Secretary of the Army to dedicate a statue.

As previously indicated, Jack drank. It got so, he told me, that he began before seven in the morning with something-and-orange juice – vodka or gin. After fifteen years of marriage, no children, Shirley left him – his drinking. She got the house in Aspen, married again. A group of friends got together with him in what is now called an intervention, told him a car was waiting downstairs along with air tickets to a Minnesota drying-out place, and he was leaving now. Tickets to the theater, luncheon dates – the hell with that. He was going. He did and it worked. After a while he re-married, to Sandra Sinclair, a youthful-looking grandmother. He was very happy with her and her children and particularly her little granddaughter.

During the time I knew him, Jack had awful teeth problems which took an eternity to resolve. Then he fell ill, was in the hospital for three months, came out, went back in, and was gone in July of 1999.

It has become a difficult matter to arrange interment at Arlington, for the cemetery is running out of space in the wake of America’s wars and its servicemen killed in action or dying of natural causes. But Jack put in more than thirty years of active and Reserve time, and in addition he was who he was. So when the time came he went to be with his grandfather the general of the armies and his brother the second lieutenant.

Jack’s burial marked the conclusion of a family that served in all the wars from before the Revolution to Vietnam, in all the ranks, places, theaters of operations, situations – or almost all – and then everything was over.