September 2017

For six years, the specter of defeat had dogged Gen. George Washington’s every thought. As advantage after advantage slipped away, the American coffers dried up, and the most promising general betrayed the Revolution, it looked more and more like Washington and his motley army would lose their fight for independence. But in September 1781, on a hilltop he had feared he might never see again, Washington could finally breathe a sigh of relief.

Three weeks earlier, he had begun a march south from the New York area, where he and his soldiers had spent most of the war. Now, for the first time since being appointed commander-in-chief in 1775, he visited his home at Mt. Vernon. Things were finally looking up for his army, too, although he couldn’t have guessed how much. On September 28, 1781, 225 years ago today, he and his allies would reach Yorktown, Virginia. There he would score his first—and last—major offensive victory. The siege at Yorktown would win the American Revolution.

As I drove through the Maryland woods to old Fort Frederick, it was hard to believe that Colonel George Washington once called this beautiful and tranquil scene a “theater of bloodshed and cruelty."

As I drove through the Maryland woods to old Fort Frederick, it was hard to believe that Colonel George Washington once called this beautiful and tranquil scene a “theater of bloodshed and cruelty."

Hoping to photograph the massive stone fort that Saturday morning in the golden light of dawn, I snuck past a sign saying that the park would not open until 8:00. The sun was just coming up, painting a golden edge on the dark gray clouds that moved rapidly across a deep blue sky.

If I were caught trespassing, I hoped the ranger would sympathize with my good intentions.

Fort Frederick sits only a mile from busy Interstate 70, above the Potomac River in the mountains west of Hagerstown, Maryland. Even though it embodies so much history, the fort is well off the path of most travelers.

In April 1960, 126 young civil rights activists joined together in song in Raleigh, N.C., as they gathered for the founding of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, better known as SNCC. “Guy,” someone shouted, “Teach us all ‘We Shall Overcome.’”

As a high school librarian, I am so pleased about your efforts to save American Heritage. I have always recommended it to our American history students for research purposes. The magazine serves a real need in education.

When I began working at Edgewood High School here in Indiana, I inherited an archive of yellowed American Heritage magazines. At long last, we had to cull them when a new, smaller library emerged from a school renovation.

Every time I tried to get rid of those magazines, I started leafing through the stories and ended up reading for hours. They are so good! I carried them around in the back of my Kia for a month or two. Then I stacked the boxes in my dining room at home for almost a year. (Bad look). Finally, I packed them upstairs to a closet in the guest room where they remain stacked from floor to ceiling.

I firmly believe that, after society crumbles, strangers from far and wide will show up at my door begging me to read those stories around the campfire about the way it once was in the United States of America.

Sharon Roualet

Library Media Educator

Edgewood High School

Ellettsville, IN 47429

It is painful to see a state such as Massachusetts — so central to our nation's past — plan to cut back even more on the teaching of American history. In recent years, renowned historical sites such as Old Sturbridge Village have reported a dramatic decrease in visits by students because of a reduced emphasis on teaching history in schools (despite the efforts of many dedicated teachers), and an increase in paperwork to justify field trips. (Parenthetically, American Heritage was launched in 1949 at Old Sturbridge Village, which still guards the original carved eagle used for our logo in its collections. This semester they launched another ambitious venture, the Old Sturbridge Village Charter School.)

We asked Tom Birmingham, former president of the Massachusetts State Senate and co-author of the landmark Massachusetts Education Reform Act of 1993, to weigh in on the current situation in his state. —The Editors

Editor's Note: We were devastated to learn that John Miller, a longtime professor of history at South Dakota State University, passed away after submitting the following essay to American Heritage. John was the author of two definitive books on Wilder, and will be sorely missed by the university community and the generations of students he inspired since joining the faculty in 1973.

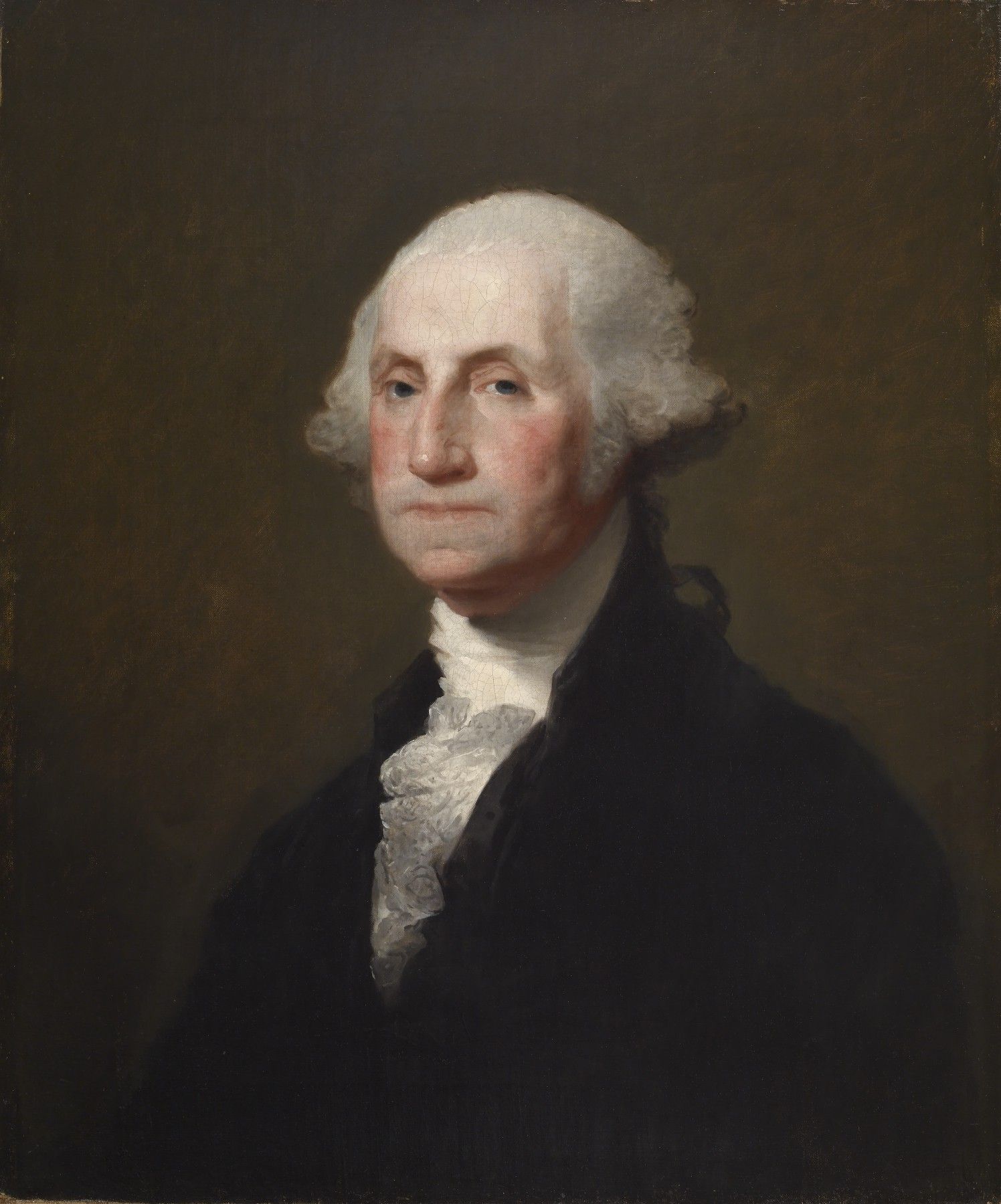

The numerous portraits of George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart are among the most famous in American history. To illustrate the essay by Michael Beschloss in this issue on the struggles, and sometimes nasty opposition, that our first president endured in his second term, we chose the last portrait that Stuart painted. In it, the Washington looks so real, so tired, almost as if he was worn out by the attacks on him and even his wife Martha. It seems as if every president has visibly aged in office.