Editor’s Note: One of the most respected historians of the Civil War and Indian conflicts, Peter Cozzens has written 17 books and is now at work on the third volume of a trilogy about the Indian wars in the American West, the Old Northwest (America’s Heartland), and the Old Southwest (the Deep South). Portions of this essay appear in the second volume, Tecumseh and the Prophet: The Shawnee Brothers Who Defied a Nation, published last month by Knopf. Mr. Cozzens’ 2016 book, The Earth is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars of the American West, won the Gilder Lehrman Prize for Military History and is the first volume in the trilogy, which will conclude with A Brutal Reckoning: Andrew Jackson, the Creek Indians, and the Epic War for the American South, projected for publication in 2023.

November 2020

Editor’s Note: Roy Morris Jr. is a contributing editor for MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History and the author of nine books, including a definitive history of the 1876 Presidential election, Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876, in which portions of this essay first appeared.

We have become all too familiar in the last year with face masks, social distancing, lost income, empty streets, and the gnawing fear of being the next to be stricken. Recently, our downtowns cities have resembled London during the Great Plague — “the streete thin of people, the shops shut up, and all in mournful silence, as not knowing whose turne might be next,” as John Evelyn penned in his diary in 1665.

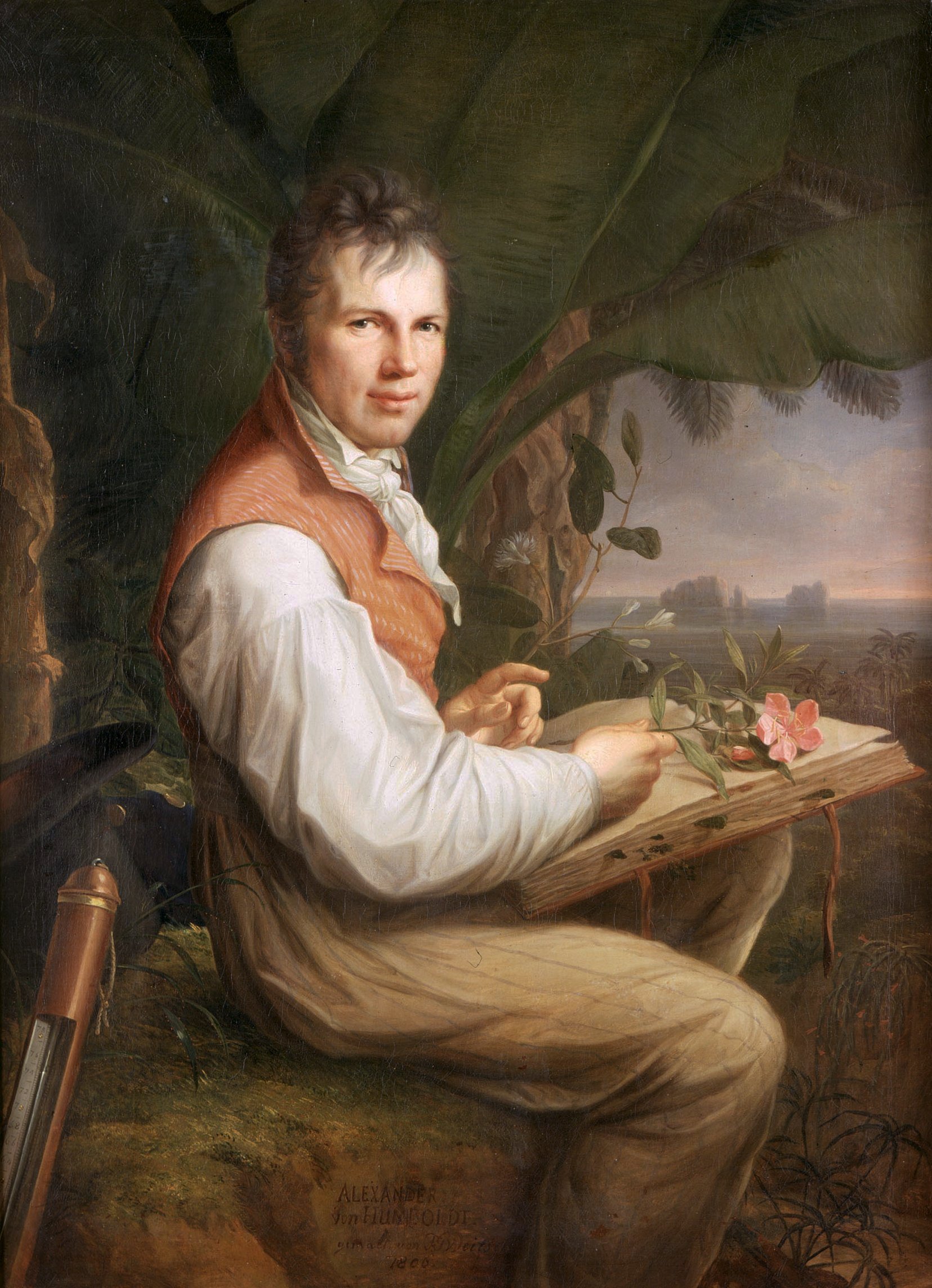

Editor’s Note: Eleanor Jones Harvey is a senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She organized the recent exhibition on Humboldt at the museum and was one of the authors of the book, Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture (Princeton University Press), in which portions of this essay appeared.

On January 27, 1920, the American flag at Mount Vernon flew at half- mast, in memory of a black woman. Visitors that Tuesday would never have guessed whom it honored: a former slave, who had lived long ago in one of the little whitewashed houses to the right of George Washington's mansion. They could easily mistake the lowered Stars and Stripes for a perpetual tribute to the Father of His Country, entombed a few hundred yards away. The superintendent who ordered the gesture that day meant no statement about racial equality. In his words, the flag commemorated a "faithful ex-servant of M.V," a woman who had earned respect by knowing her place. Thirty years earlier nobody knew Mount Vernon better than Sarah Johnson. She had lived there almost half a century by then, longer than even Martha Washington had. Born to a teenage mother in 1844, Sarah grew up surrounded by kin, celebrated the births of new siblings and cousins, grieved for relatives sold away. She trained from child- hood for a lifetime of domestic service, but not the one she got.