"Ich bin ein Berliner": A Kennedy Mistake?

After the President’s inspiring speech, Soviet leaders were left to wonder: Was Kennedy a peacemaker or aggressor?

Anticipating a West German tour that on June 26, 1963, would take him to Berlin, President John F. Kennedy expressed worry. Charles de Gaulle had recently gone to Germany and won wide acclaim there. Kennedy didn’t want to just follow in the French presidents footsteps.

"My money's on you, Mr. President," the ambassador to Germany, Walter C. Dowling, reassured him.

"We’ll see, we’ll see, we’ll see," Kennedy replied.

The President would be in Berlin at a critical moment. The Cuban Missile Crisis the previous October weighed heavily on him. In a subsequent private exchange of letters, he and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had broached the possibility of banning nuclear testing. By the early summer of 1963, JFK was aggressively seeking detente. He chose a June 10 commencement address at American University in Washington, D.C., to deliver what became known within the White House as the peace speech.

He offered a vision of not merely peace in our time, but peace for all time. He announced that he, Nikita Khrushchev, and Britain’s Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had agreed to high-level discussions in Moscow on a nuclear test ban treaty. And he held out an olive branch to the Soviets:

"Some say that it is useless to speak of world peace or world law or world disarmament and that it will be useless until the leaders of the Soviet Union adopt a more enlightened attitude. I hope they do. I believe we can help them do it. But I also believe that we must reexamine our own attitude—as individuals and as a nation—for our attitude is as essential as theirs."

It was in this spirit that Kennedy left on the 10-day European trip that would take him not only to West Germany but to Ireland, Britain, Italy, and the Vatican. He intended to deliver a conciliatory speech in Berlin meant for the ears of the Soviets and East Germans. But there was an ominous development. On June 23, the day he landed in Bonn, The New York Times reported that tensions had flared at the Berlin Wall over new East German restrictions along a border-crossing point.

Meanwhile any lingering doubts Kennedy may have had about walking in de Gaulle’s shadow were quickly overwhelmed by a sea of West Germans calling for "Ken-ne-DEE! Ken-ne-DEE!" When he entered Berlin on June 26 the Universal-International newsreel narrator marveled that it seemed that two and a half million—everyone in the city—had turned out. Newsreel footage shows Kennedy riding in an open car, standing boldly upright as he made his way through Berlin. He traveled over 35 miles of local streets.

A crowd 150,000 strong was gathering at the city square known as Rudolph Wilde Platz. But first the President would stop to see the wall for himself.

The barrier separating Communist East Berlin from democratic West Berlin had gone up in the early morning darkness on August 13, 1961, on Khrushchev’s orders. Groggy citizens looked on as work details began digging holes and jack-hammering sidewalks, clearing the way for the barbed wire that would eventually be strung across the dividing line, as Kennedy Library historians recount those first uneasy hours. Armed troops manned the crossing points between the two sides and, by morning, a ring of Soviet troops surrounded the city.

Berlin, in the historian’s words, was at the heart of the Cold War.

The West would watch, horrified, as desperate East Berliners braved both barbed wire and armed guards to cross into the western part of the city. The Soviets had threatened to sign a separate peace treaty with East Germany, a move that could further isolate West Berlin within East Germany.

Kennedy’s entourage made two stops at the wall. Twice he climbed platforms to peer east over barbed wire and concrete. The newsreel narrator proclaimed it a moment charged with drama as the leader of the world’s greatest democracy views the symbol of mans degradation under a dictatorship. The narrator speculated that in the distance, the President may have seen some East Germans who waved furtively.

Whatever he saw, it changed him and the course of history.

"I once heard McGeorge Bundy [Kennedy’s director of the National Security Council] say that in Berlin President Kennedy was affected by the brute fact of the Berlin Wall," recalls Frank Rigg, a curator at the Kennedy Library. "He was affronted in a very direct way by the wall, the reason for it and by what it symbolized."

From the wall the President’s motorcade made its way to the city square. Kennedy, who had said very little after looking over the wall, was putting together a new speech in his head, writes Richard Reeves, in his book President Kennedy: Profile of Power.

Once at the platz, the President quickly dispensed with the civic pleasantries, recognizing the mayor, the German chancellor, and U.S. Army Gen. Lucius D. Clay, who had overseen the 1948-49 Berlin airlift. That done, he marked a new line in the sand between East and West in not quite 600 words. It was among the most stirring speeches of his Presidency- and in the history of freedom.

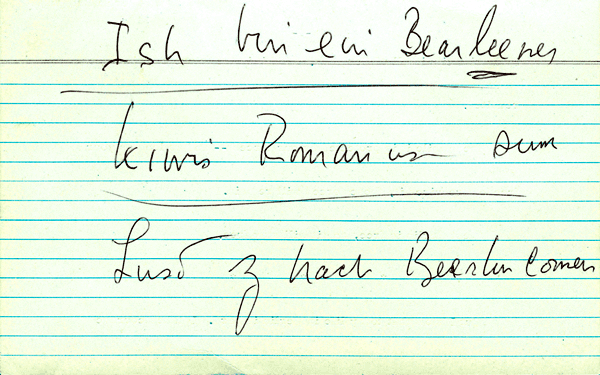

"Two thousand years ago," he began, "the proudest boast was civis Romanus sum. Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is Ich bin ein Berliner." In films of the speech, an index card is visible in Kennedy’s hand. He had written in red ink the Latin for "I am a Roman citizen" and a phonetic spelling for Berliner, as Bearleener.

He threw down the gauntlet, audibly jabbing the lectern each time he repeated a now famous refrain:

"There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world. Let them come to Berlin. There are some who say that Communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin. And there are some who say in Europe and elsewhere we can work with the Communists. Let them come to Berlin. And there are even a few who say that it is true that Communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lass sie nach Berlin kommen. Let them come to Berlin."

Kennedy’s euphoria matched the crowds. His rhetoric echoed his inaugural-address promise to oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty. The American President had given Berliners a pledge of the West’s adamant defense of their city, explained Riggs. He had said that he was one of them.

There was just one problem. As Reeves writes: "In his enthusiasm, Kennedy, who had just given a peace speech and was trying to work out a test ban treaty with the Soviets, had gotten carried away and just ad-libbed the opposite, saying there was no way to work with Communists."

"Oh, Christ," the President exclaimed, when he realized what he had done.

Later, at the Free University of Berlin, he tried to put the genie back in the bottle, saying, I do believe in the necessity of great powers working together to preserve the human race. The Soviets were left to wonder: Was he now Kennedy the peacemaker or Kennedy the aggressor?

At any rate, treaty talks went ahead. And on July 26 Kennedy addressed the nation from the White House. Negotiations on a limited treaty had been successfully concluded in Moscow the day before. The treaty prohibited all nuclear testing in the atmosphere, space, and underwater. Yesterday, Kennedy declared, a shaft of light cut into the darkness.

The pact was signed by American, British, and Soviet representatives on August 5. The Senate ratified it on September 23, and Kennedy signed it on October 7. Less than two months later he would be assassinated.

In 1989 free travel finally flowed between East and West Berlin. The wall came down. A concrete section was taken to the Kennedy Library in Boston and placed on public display. And Kennedy's words at the wall—like Ronald Reagan’s equally impassioned and provocative plea to "tear down this wall" 24 years later—live on far past the Cold War that provoked them.