From its birth in pagan transactions with the dead to the current marketing push to make it a “seasonal experience,” America’s fastest-growing holiday has a history far older (and far stranger) than does Christmas itself.

-

October 2001

Volume52Issue7

In 1517, Martin Luther took a stand on it. In 1926, Houdini made his final exit on it. In 1938, Orson Welles perpetrated a national hoax on it. Today, 70 percent of American households open their doors to strangers on it, 50 percent take photographs on it, and the nation drops more than six billion dollars celebrating it. The night is Halloween, of course, and the history of its rise is as unlikely as any ghost story. Halloween has become the darling of American holidays. Only Christmas outearns it. Only New Year’s Eve and Super Bowl Sunday outparty it.

The festival was not always so lighthearted. For the Celts of ancient Britain, Scotland, Ireland, and northern France, November 1 marked the end of harvest, the return of herds from the pasture, the time of what was known in folk wisdom as “the light that loses, the night that wins,” and the start of the new year. It was also the festival of Samhain, who may or may not, depending on the source, have been the god of the dead but who remains a favorite of modern witches, neo-pagans, and fans of Walt Disney’s 1940 film Fantasia. On October 31, the last night of the old year, spirits of the deceased were thought to roam the land, visiting their loved ones, looking for eternal rest, or raising hell. They particularly liked to wreak havoc on crops. They were also capable of revealing future marriages and windfalls, and illnesses and deaths. It was incumbent upon the living, therefore, to welcome them home with food and drink, to propitiate the grudges they might still be carrying, or to light bonfires and carry lanterns made from hollowed-out turnips carved into frightening faces to keep them away. The bonfires also came in handy for immolating vegetable, animal, and human sacrifices to Samhain. In other words, anything might happen on this hallowed night, or, given the sketchy state of modern scholarship about ancient Druid practices, we can easily imagine anything happening. Most accounts of the Celtic origins of Halloween, including this one, should be taken with a pumpkin seed of skepticism. About all we can be certain of is that some festival marked the onset of the long, cold northern winter when living conditions grew raw, food was scarce, and many died.

By the first century A.D., Rome had conquered Celtic lands, Romans and Celts were living cheek-by-jowl in small villages, and Pomona, the Roman goddess of orchards and the harvest, whose festival was celebrated on November 1, was cohabiting happily with Samhain. But if the Romans, who associated Pomona with the apple and therefore with love and fertility, lent the macabre Celtic festival sex appeal, the church gave it an air of respectability and a new name. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III, acting on the theory that if you can’t beat paganism, which was still rife throughout Christendom, you’d better join it, moved All Saints’ Day (which had been consecrated the century before when the number of saints outstripped the days of the year), from May 13 to November 1. The night before became All-hallows Eve, or Hallowe’en, and the old Celtic practices became Christian pieties. Instead of appeasing spirits with food and wine, villagers gave “soul cakes” to poor people who promised to pray for departed relatives. Instead of dressing up as animals or spirits to frighten away the dead, parishioners of churches that couldn’t afford genuine relics dressed up as saints. As the church militant marched around the globe, its hybrid Celtic-Roman-Christian celebration chased after it like a faintly disreputable but fun-loving camp follower. It was one of the many church practices that incited Martin Luther to action. Whether Luther chose October 31 to nail his theses to the church door to protest the practice of purchasing indulgences or to take advantage of the crowds that would be out on a festival eve—or whether, in fact, he ever actually nailed anything anywhere (and modern scholarship is beginning to doubt that he did)—tradition has him hammering on Halloween.

The Reformation’s abolition of saints’ days should have put an end to the celebration of All-hallows Eve in Protestant countries, but the festival that had survived Roman invasion and Christian conquest had gained too firm a hold on popular imagination and practice. In 1606, when the British Parliament declared November 6 a day of national thanksgiving for the foiling of the plot by the Catholic revolutionary Guy Fawkes to blow up the Protestant House of Lords the year before, the new holiday, coming just five days after the old, took on many of Halloween’s trappings while assuming an anti-Catholic and anti-Popish flavor. Bonfires lit the autumn evening, revelers carried lanterns of hollowed-out turnips carved into grotesque faces, and no one worried too much about the rationale for celebrating the quickening of a crisp new season.

But what was acceptable in the Old World was anathema in the New. The colonies were, of course, a patchwork of customs. From its earliest days, Catholic Maryland celebrated All-hallows Eve, and Anglican Virginia, by allowing the celebration of saints’ days, simply put the stamp of approval on what its subjects were already doing. But New England soil was notoriously hostile to holidays. Early Northern settlers did not even celebrate Christmas; indeed, only three occasions—muster day, election day, and the Harvard commencement—merited official recognition until a new holiday, Thanksgiving, began to find its way onto the New England calendar during the 1670s. Despite the best efforts of Puritan church officials, however, New England settlers refused to relinquish Guy Fawkes Day. In 1685, Judge Samuel Sewall noted in his diary, “Friday night being fair, about two hundred hallowed about a fire on the Comon.” Almost a century later, costumed young men and boys paraded with “Guys” or “popes” of straw for the bonfire, and John Adams wrote, “Punch, wine, bread and cheese, apples, pipes, tobacco and Popes and bonfires this evening at Salem, and a swarm of tumultuous people attending.” Soon Britain’s day of thanksgiving was getting mixed up with the colonies’ drive for independence, as New Englanders burned effigies of the Stamp Man along with those of the Pope and the devil.

The New England celebration of Guy Fawkes Day rather than Allhallows Eve had to do with more than Puritan hatred of Catholic habits. Halloween still retained many of its pagan associations with the spirit world, and nothing struck fear in the Puritan heart so forcefully as witchcraft. New England led the way in persecuting witches, but every colony prescribed a punishment for the use of magic, and there was a reason for, if not a rationality to, the laws. In the colonies, astrological almanacs outsold Bibles.

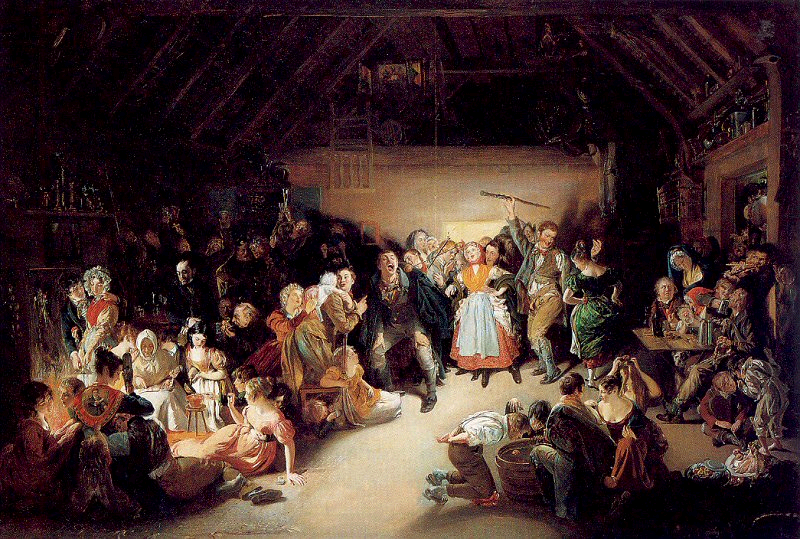

As the new nation grew and sprawled, its far-flung citizens sought occasions for community celebrations. In the fall, families came together to husk corn, pare apples, and make sugar and sorghum. Soon these task-oriented gatherings gave way to “play parties,” which promised nothing more than a good time. Revelers told stories, traded gossip, and—though many churches forbade dancing and that instrument of the devil, the fiddle—shouted, sang, and clapped while they swung their partners round in the first American square dances. Perhaps most important to farm families living at great distances from one another, these gatherings brought together men and women of marriageable age. Play parties were not a direct descendant of Halloween; they did not occur on any particular night, had no religious affiliation, and were more concerned with producing future generations than with honoring or placating past ones. But they did keep alive certain Halloween traditions, such as telling ghost tales and divining future romance with apples and nuts, so that when a new wave of immigrants arrived, the old holiday customs they brought with them didn’t seem quite so alien.

In the wake of the famine of 1820 and the even harsher devastation beginning in 1846, more than a million Irish Catholics arrived in the urban areas of North America. Starved and penniless, they brought little with them beyond their traditions. Though they celebrated All Saints’ Day, they gave over its eve to more pagan practices. Irish girls peeled apples, roasted nuts, unraveled yarn, stared into mirrors, dipped their hands into a series of bowls while blindfolded, cooked dinners in silence, and played with fire to find out whether and whom they would marry. In place of the turnips they had used at home, revelers carved out indigenous pumpkins to light the way as they went from house to house. Instead of dressing up as saints in church parades and begging for soul cakes in return for prayer, these new urban Irish slipped into secular costumes and went from house to house, soliciting handouts.

Where there were Irish on Halloween, there were often “little people” who had a tendency toward vandalism, and although most Irish immigrants had settled in the cities, the tradition of Mischief Night spread quickly through rural areas. On October 31, young men roamed the countryside looking for fun, and on November 1, farmers would arise to find wagons on barn roofs, front gates hanging from trees, and cows in neighbors’ pastures. Any prank having to do with an outhouse was especially hilarious, and some students of Halloween maintain that the spirit went out of the holiday when plumbing moved indoors.

Despite a strong Irish influence, in the years after the Civil War Halloween practices still varied widely throughout the country. Witches roamed among the Scottish and German settlers of Appalachia, and Halloween was their special night. In the South, voodoo customs associated the holiday with witchcraft, charms, and deceased ancestors. Southwesterners celebrated a joyous Day of the Dead by taking food, drink, flowers, and candles to the graves of loved ones at midnight on November 1 and staying till the sun rose the next morning.

But America was becoming a more uniform nation. Railroads, the telegraph, and magazines were blurring sectional differences. In 1871, women in every part of the country, at least women of the middle class, opened their issues of Godey’s Lady’s Book and read one of the first articles published about Halloween. Other magazines and newspapers followed with stories, poems, illustrations, and suggestions for celebrations. But a funny thing happened to Halloween on its way to national prominence. It severed its ties with restless spirits, destructive pranks, and, perhaps most important, working-class Irish Catholic traditions and became a proper Victorian lady—safe, sinless, and romantically inclined. By the end of the century, it was so intimately associated with polite social gatherings and innocent amorous pursuits that celebrants were hanging mistletoe on October 31.

Halloween entered the twentieth century stripped of occult associations and religious significance. Populist city fathers with boosterish hearts, alert for ways to promote community spirit and Americanize a motley immigrant population, recognized its potential. Allentown, Pennsylvania, sponsored the first annual Halloween parade, and in 1921 Anoka, Minnesota, held the first citywide party. Halloween had left the parlor, taken to the streets, and discovered its nationality. Shortly after World War I, a young Ernest Hemingway wrote a sketch in which the hero, lying wounded in an Italian hospital, hears the sound of the armistice celebration and remembers neither the Fourth of July nor, despite the November date, Thanksgiving, but Halloween at home.

Now that the holiday had got another whiff of fresh air, the scene was set for the practice that more than any other symbolizes contemporary Halloween. Medieval villagers had begged soul cakes and Irish immigrants had extorted handouts, but not until the 1920s did costumed children begin going from door to door to trick-or-treat. One of the first mentions of the practice appears in a 1920 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, and by the 1950s, it was an established ritual, although one Depression-bred student of the subject insists that in North Dakota in 1935, no one had ever heard of it and chides later generations for having “sold their rights to rebellion for some sugar in expensive wrappings.”

Not all the young made such a craven deal, however. If the Victorian age had denatured the more raffish aspects of the holiday, it had not wholly obliterated them. While some youths had lingered under the mistletoe in the parlor, others had continued to roam the countryside on the lookout for unguarded livestock or remaining outhouses, and even today many law-abiding males of a certain age remember that dressing up and going from house to house was fine for girls, but boys were looking for trouble. Many of them found it. As families moved to the city, the old purportedly innocent high jinks gave way to more serious vandalism. Youths slashed tires, stole gas caps, and rang false fire alarms, all in the spirit of good fun. In Queens, New York, in 1939, a thousand windows were broken.

Just as city officials were trying to find ways to channel all this youthful energy into constructive civic action, like raking lawns and mending fences, America entered World War II, and pranks and vandalism became sabotage and treason. The Chicago City Council abolished Halloween and called on the mayor to make October 31 Conservation Day. “Letting air out of tires isn’t fun anymore,” wrote the superintendent of the Rochester, New York, schools. “It’s sabotage. Soaping windows isn’t fun this year. Your government needs soaps and greases for the war…. Even ringing doorbells has lost its appeal because it may mean disturbing the sleep of a tired war worker who needs his rest.”

After V-J Day, children went back to trick-or-treating, youths to making trouble, and civic leaders to trying to head it off with community celebrations. Then, in 1950, a group of students from a Philadelphia-area Sunday school sent the $17 they had collected trick-or-treating to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and another holiday tradition was born. A newly rich and powerful America celebrated Halloween by lending a helping hand to less fortunate peoples around the world. But as the certainties of the fifties gave way to the rebellions of the sixties, which many Americans didn’t experience until the seventies, an innocent holiday became an opportunity for tragic accidents.

In 1970, a five-year-old boy died from eating heroin, supposedly laced through his Halloween candy, but actually filched from his uncle’s stash; a number of other scares, most of them unfounded, followed; and trick-or-treating began to decline. In the late 1980s, however, as President Reagan’s “morning in America” headed toward high noon, costumed children began venturing back onto the streets, and by 1999, 92 percent of America’s children were trick-or-treating. In fact, the spirit and intentions of the old pagan holiday of darkness had finally become so sunny that an affluent Indiana suburb began busing in less well-to-do children to share the goodies. Unfortunately, a glut of less affluent trick-or-treaters roaming the well-kept lawns soon led residents to move Halloween to another night, advertised only in the community association’s newsletter.) On a more entrepreneurial note, in 1987, a Canadian good neighbor began handing out stocks to the first 100 trick-or-treaters who showed up, some of whom, once the word was out, traveled more than 200 miles to beef up their portfolios. When the shares took a downturn as the rest of the market soared, the financial Good Samaritan began questioning the values he was fostering and put an end to the practice.

Halloween is a plastic holiday. Lacking the religious foundations of Christmas, Easter, and their cousins from other cultures, or the patriotic underpinnings of Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July, or even the single-minded sentimentality of the synthetic Mother’s Day (hatched by Anna Jarvis, an unmarried childless woman who never got over having abandoned her mother for a career, and subsequently seized upon by the flower, telegraph, and greeting-card industries), Halloween could be mauled and molded to fit the needs of each generation. Puritans, intent on survival in a new world and salvation in the next, ignored it. A hard-pressed immigrant population let off steam in its honor. A Victorian society tamed it. World Wars I and II and even Vietnam undermined it. And a newly powerful postwar nation gave it a social conscience. Even the masquerades chosen commented on the era in which they were worn. In 1973, Time magazine reported that first prize for the most frightening costume at a Halloween party went to a child wearing a Richard Nixon mask, and, in 1986, 49 schoolteachers marched as Imelda Marcos’s shoes. But perhaps the most significant sign of the times is contemporary Halloween’s strenuous consumerism.

The process, though recently accelerated, began almost a century and a half ago. In the decades following the Civil War, the American business community stopped viewing holidays as impediments to production and began recognizing their potential as incentives to consumption. In 1897, one of the leading trade papers of the time, the Dry Goods Economist, bemoaned those out-of-date entrepreneurs who still regarded “holidays as an unavoidable nuisance” resulting in “the loss of trade.” Three years later, the Dry Goods Chronicle urged its readers: “Never let a holiday… escape your attention, provided it is capable of making your store better known or increasing the value of its merchandise.” Advertisers took up the cry by promoting seasonal campaigns.

Though Halloween, compared with some of the more traditional holidays, was a slow starter in the race to commercial prominence, its fixed time slot, unlike the wandering Easter and Thanksgiving, and its established icons, such as jack-o’-lanterns, witches, and black cats, ultimately made it a marketer’s dream. Of the six billion dollars raked in on the holiday today, almost two go for sweets. Costumes account for between a billion and a billion and a half. The remaining sum buys decorations and food and drink for friends, but if you think that means some apples for bobbing, a pumpkin from your nearby road stand, and a cardboard skeleton with crepe-paper limbs, you’re hopelessly out-of-date.

Americans buy enough Coors beer for their Halloween parties to increase seasonal sales 10 percent. A Syncromotion Skeletal Grim Reaper, which talks and sings, sells for $199.95; a Fog Master to give lawns that haunted look, $99.95. In addition to the products, there are the promotions. In the mid-nineties, companies decided to make Halloween not just a “candy occasion” but a “seasonal experience.” The results of this process include orange and black Rice Krispies, a drinking straw twisted around a plastic eyeball at Taco Bell, and a free trip to Alcatraz for the lucky winner who has purchased a Barq’s root beer. When Nabisco began filling Oreos with orange rather than white cream, demand for the garish result increased cookie production by 50 percent. The movie industry has long mined the potential of the holiday, but recently studio competition has become fiercer as Universal and Disney theme parks duel for the Halloween dollar, with Universal selling beer, blood, and gore and Disney sticking to its clean-cut image and offering discounts to entice the youngest Halloween revelers.

One cultural critic argues commercialization of the holiday has gone so far that, when he made an informal study by asking his local trick-or-treaters what they would do if he said “trick,” 83.3 percent of the admittedly small and unscientific sample that rang his doorbell answered, “I don’t know.” The rite was simply “a rehearsal for consumership without a rationale. Beyond the stuffing of their pudgy stomachs, they didn’t know why they were filling their shopping bags.”

Even community festivities have become big business. What started in 1973 in New York City’s Greenwich Village as a small parade organized by a puppeteer and theater director and grew into a riotous celebration of gay life has become a commercial enterprise that attracts tens of thousands of participants, more than a million spectators, and scores of international film and television crews, and pumps $60 million into the local economy.

The popularity of the parade as well as similar, if less splashy, parties in San Francisco, Georgetown, and Key West, to name only a few places, points up another contemporary change in Halloween. Although children still claim the night, adults are once again taking it over. The Victorians dedicated the holiday to decorous romance; our less restrained age makes it an occasion for wild parties, heavy drinking, and, often, sexual exhibitionism. The beer and liquor industries blitz the media with ads. Men and women spend small fortunes and long hours dressing or undressing as their favorite fantasies. While juvenile celebrations become more controlled, with parents vigilant against excessive sugar consumption shepherding their children from house to house, adult festivities grow more licentious.

They also grow more violent. In San Francisco in 1994, when gay bashers invaded the annual Castro Street revel, police officers donned riot gear, dodged bottles, detained nearly a hundred people, and confiscated several loaded guns. In Detroit between 1990 and 1996, 485 properties went up in flames on Halloween Eve, which is known there as Devil’s Night. In New York a decade ago, a group of costumed teenagers descended on a homeless camp with knives, bats, and a meat cleaver, shouting, “Trick or treat,” and leaving one dead and nine injured. One of Halloween’s chief attractions—slipping into a mask to slip out of constraints—has turned deadly. Sometimes the violence isn’t intentional. Last year in Los Angeles, a policeman summoned to a noisy party shot and killed an actor brandishing a fake weapon.

A more subtle sort of violence is the damage done to young psyches. In 1911, Sears advertised wigs, masks, and makeup to enable children to play at being “Negro”—“the funniest and most laughable outfit ever sold.” Feathered headdresses were always a favorite of small boys, and in my own youth I remember being wildly envious of a friend’s harem costume. My mother, whose political consciousness was insufficiently raised but whose sartorial sense was finely honed, may have put her foot down for the wrong reason, but as current critics have pointed out, there is something offensive about pampered American children playing at being members of oppressed minorities and natives of Third World countries.

The greatest opposition to Halloween today, however, comes not from fearful parents, politically correct posses, or the foes of consumerism but from the religious right. Christian conservatives see the holiday as nothing less than the celebration of Satan and have set out to exorcise it. Some churches stage “trunk or treat” parties: Parishioners in the parking lot hand out candy from the trunks of their cars and invite children to step into the church for a party. A less-benign custom is the dramatized glimpse of hell. Congregations stage “mortality plays” featuring teenage girls undergoing bloody abortions, AIDS victims dying agonizing and unredeemed deaths, and businessmen who didn’t have time for Jesus burning in hell. In 1996, The Wall Street Journal reported that some 300 variations of these lurid portrayals of the wages of sin were intimidating more than 700,000 potentially savable souls, and the number was still growing.

But, if the religious right would like to do away with Halloween, mainstream America wants to expand it. One method is the mailing of the holiday. Merchants dress up their stores and salespeople and invite children into the mall to celebrate. Parents, fearing sabotaged treats and possible violence elsewhere, gladly deliver their progeny to temperature control and security patrols. The message is clear: You may not be able to trust your neighbor but you can put your faith in your local Starbucks.

Over the years, Halloween has shown an enduring malleability and a terrier-like tenacity to survive religious persecution, class prejudice, Victorian politesse, and consumerist inflation. Still, all the adaptability and advertising and marketing in the world couldn’t keep Halloween alive if Americans weren’t yearning for what it has to offer. Candy Day, energetically touted in the early part of the twentieth century, never sent the nation out to buy boxes of sweets for loved ones on the second Saturday in October.

Why have Americans, so admirably skeptical and adamantly opposed to adopting other holidays, taken to their hearts this originally scary, often silly festival? Many say it reminds them of their childhood, which baby boomers are notoriously reluctant to relinquish. And maybe it reminds some others of the childhood they wish they’d had. Since people don’t go home for Halloween as they do for Thanksgiving and Christmas, there is less likelihood of parental disappointment, sibling squabbles, free-floating depression, and the other symptoms of the disquiet we are told afflicts America’s families. Moreover, though recently cornered by adults, Halloween is still identified with children, and while our society may quarrel over the expensive realities of raising children, like health care and education, it cherishes the idea of childhood. But perhaps the greatest attraction of the holiday is that it no longer has any reason for being. It is not a night to worship the God of our choice, honor the dead, celebrate the nation’s past, take stock for the future, or woo a loved one. It is simply an occasion for fun. Organized activities permit safe and sanitized rebellion. Costumes camouflage identity, blur status, and change gender. Masks provide a moral holiday.

For one night a year, we can act out whims and realize fantasies. Men can be women, children adults, milquetoasts heroes, good girls bad, devils saints, and vice versa. For a single night we all can star in the roles of our choice. The secret of Halloween’s success is that it is more than a holiday. It is a brief and titillating vacation from our lives and ourselves.