The “Miracle Mets" of '69 Win the World Series

Bruce Watson is a Contributing Editor of American Heritage and has authored several critically-acclaimed books. He writes a history blog at The Attic.

Youth, hope, and fresh arms have a way of making things happen, but with all the amazin’ catches, the shoe polish ball, and the home runs by banjo hitters, there was something downright miraculous propelling the New York Mets to World Series' victory.

Though neither the best nor the worst of times, 1969 was a year of miracles. Two moon landings. Techno-wonders — the first ATM and the first message over what would become the Internet. Woodstock drew a half million for three days of music and mud. And the Beatles released “Abbey Road.” Take that, 1968!

But for those of a certain age, a certain city, no miracle outshines the one of a half-century ago today. Sport abounds in Cinderella teams, yet none ever touched hearts and hopes like those “Miracle Mets.”

By 1969, the Mets held enduring records for incompetence. The National League expansion team was so hapless, so bumbling, yet so lovable. “Come and see my amazin’ Mets,” manager Casey Stengel proclaimed. “I’ve been in this game 100 years but I see new ways to lose I never knew existed before.”

Speaking through comedian George Burns, playing the title role in the comedy “Oh, God,” the deity says, “I don’t do miracles. They’re too flashy… The last miracle I did was the 1969 Mets.

The Mets dropped pop flies. They threw to the wrong base. They collided in the outfield. The Yankees had “The Mick” and “The Moose.” The Mets had Choo Choo and Marvelous Marv. “The Mets were anti-matter to the Yankees,” New Yorker writer Roger Angell said. “There’s more Met than Yankee in all of us. What we experience in our day-to-day lives is a lot more losing than winning, which is why we loved the Mets.”

In their debut season, the Mets lost 120 games, then proved that record no fluke by finishing last for years on end. Though they climbed to 9th in 1968, the following spring, Las Vegas set 100-1 odds against a pennant.

But these were different Mets. No longer tired veterans, the 1969 Mets were young — an entire starting lineup and pitching staff under 26. So although they started out playing .500 ball, they embodied the hope that hangs in every 3-2 pitch.

In early June, manager Gil Hodges closed the locker room for a post-game talk. Hodges, beloved veteran of the Brooklyn Dodgers, did not shout. He did not scold. He merely told the fresh faces that they were better than this. And better they became, winning their next 11 and jumpstarting a pennant race with the Chicago Cubs.

On September 1, the Mets were five games out of first. Then the team caught fire. Aces Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman won start after start. Cleon Jones was leading the league in batting. And the Mets kept winning. They went 24-8 in September and ran away with the division. Asked by reporters to “tell us what it proves,” Gil Hodges sat back in his office chair. “Can’t be done,” he said.

Against Hank Aaron’s Atlanta Braves, the Mets swept the league championship. “We ought to send the Mets to Vietnam,” Atlanta’s general manager said. “They’d end the war in three days.”

Then the young players shook themselves, and perhaps shook with fear. For the World Series pitted them against the best team baseball had seen in a decade, the Baltimore Orioles. Along with Frank and Brooks Robinson, the Orioles had three 20-game winners and, with 109 wins on the season, the smug sense that no other team was in their league. But Gil Hodges called another clubhouse meeting. “You guys don’t have to be anything but what you’ve been,” he told them. Then he let them loose.

The Mets lost the opener in Baltimore but won the second. And rightfielder Ron Swoboda realized, “We can play with these guys.” When the Series moved to New York, the phrase “homefield advantage” took on a new meaning.

It took something special to be a Mets fan. Patience. Dreams. And volume. From their first season at the old Polo Grounds, Mets’ fans brought airhorns and that loudmouth New York brashness to every game. In 1964, Shea Stadium turned the volume up to 11. Built in the flight path of LaGuardia Airport, Shea was an echo chamber, where every play had 10,000 announcers and every pitch drew taunts and “No hittah heah, no hittah.” The Orioles would never know what hit them.

Game Three was the Mets all the way, winning 5-0. Centerfielder Tommie Agee provided the miracles, racing into leftfield to snag one ball, snowcone style, then sprinting halfway across the field to pull another ball seemingly out of the dirt in deep right.

In Game Four, the Mets clung to a 1-0 lead into the ninth behind Tom Seaver. But two singles put the tying run on third. Brooks Robinson then lined a pitch to right. “If you look at that play, it’s a base hit,” Ron Swoboda said later. “And then all of a sudden in the frame comes this maniac, diving, backhanding, and somehow coming up with the ball, and I would say to myself, ‘This doesn’t make any sense either.” Swoboda made the miracle catch, but the runner tagged up and scored to tie it. Another miracle, please?

In extra innings, the Orioles’ played like the ‘62 Mets. A misplayed blooper, a walk, and a bunt thrown away put the Mets one win from the impossible.

October 16, 1969. There are only seven TV channels, but a new one, PBS, is about to debut “Sesame Street.” At the movies, “Easy Rider” will soon be joined by “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” On TV, “Laugh-in” and “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour” top the ratings. On the street, America is still reeling from a nationwide moratorium on Vietnam the day before, a hundred thousand marching. But in an echo chamber on Long Island. . .

The Orioles went up 3-0 in the third. Hope was on hold. Then in the sixth, an inside fastball nicked Cleon Jones on the foot. The ump, however, hadn’t seen any contact. Gil Hodges ran to the plate. With him was the ball that had bounced, miraculously, into the dugout. Look, Hodges said, pointing to the ball. Shoe polish. The umpire awarded Jones first base. A homerun quickly put the Mets back in the game. An inning later, Al Weis, a journeyman infielder who hit just seven homeruns in his life, homered to tie the score. Then in the bottom of the eighth, a double, a bloop fly, and a misplayed grounder. Three outs away.

Jerry Koosman walked to the mound.

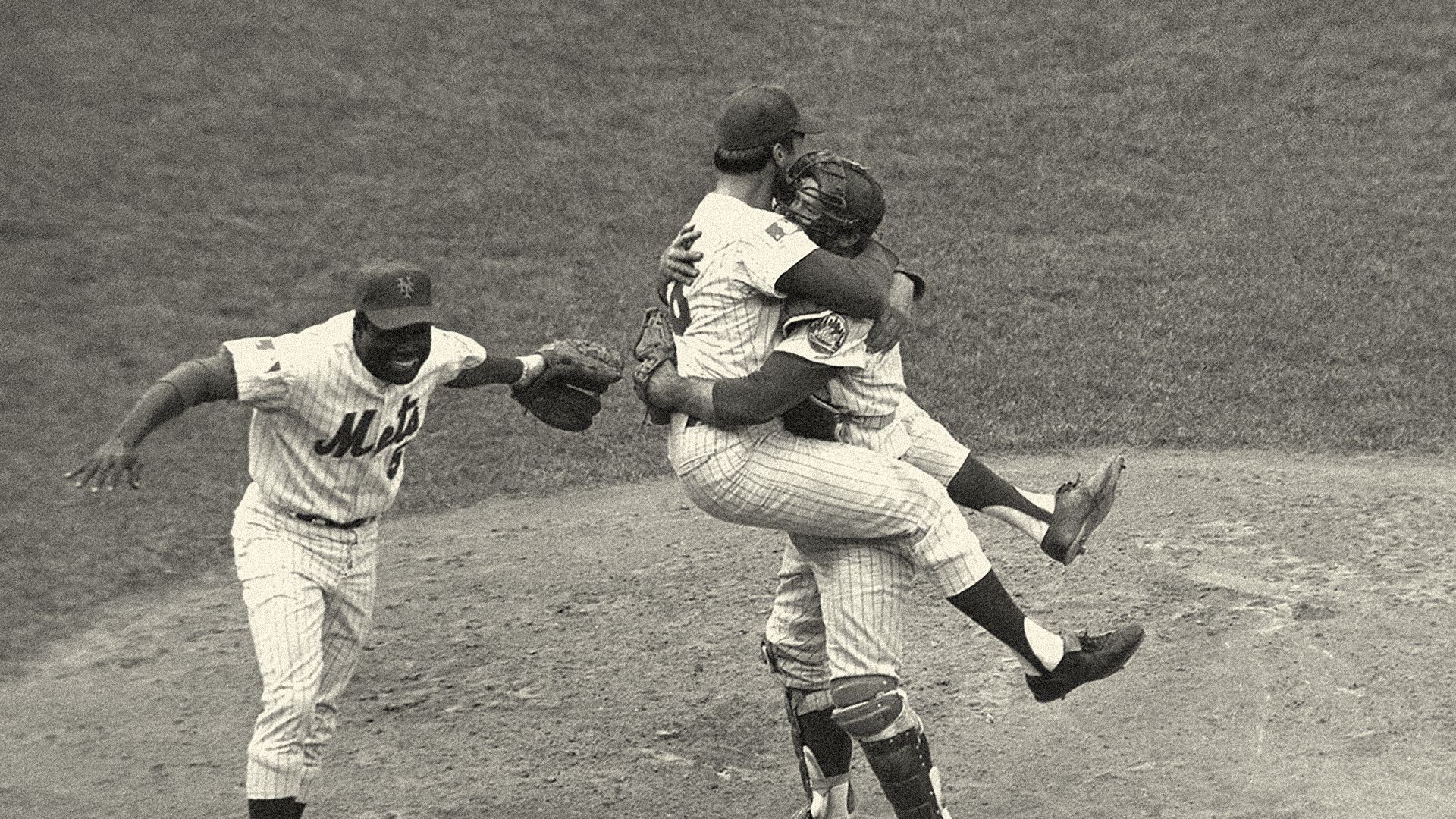

“It was so noisy you couldn’t even hear the bat hit the ball,” he recalled. Koosman walked one batter but got the next two. Then Dave Johnson hit the ball to deep left. Hearts stopped. A homer would tie it. But the ball held up. Cleon Jones clutched it on the warning track, and bedlam broke loose.

On a field swarming with crazed fans, some ripping up souvenir turf, a lone man stood in the stands. The man was famous at Shea. “Sign man” Karl Ehrhardt seemed to produce a pre-printed message for every occasion. Now he stood, as his beloved Mets popped champagne in the dugout, as a mob took over the field. Ehrhardt’s sign read, “THERE ARE NO WORDS.”

Nor is there any explanation of those Miracle Mets, who stumbled again the following year. But youth, hope, and fresh arms have a way of making things happen. Still, in all the amazin’ catches, the shoe polish ball, the homeruns by banjo hitters, there must have been something more. Several years later, God himself offered an answer. Speaking through comedian George Burns, playing the title role in the comedy “Oh, God,” the deity says, “I don’t do miracles. They’re too flashy… The last miracle I did was the 1969 Mets. Before that, I think you have to go back to the Red Sea. That was a beauty.”