The Story of Satchel Paige

Editor's Note: This summer marks the centennial of the Negro Leagues, the first professional baseball teams for African Americans in the U.S. Among the most famous players to come out of those leagues was Leroy Robert "Satchel" Paige, the first Black pitcher to start an American League game and, according to some fans, one of the best pitchers of all time. Author Ryan Powers explores Paige's backstory and rise to fame in the latest episode of his Almost Immortal history podcast, which you can find and/or subscribe to here.

In the warm Ohio summer air of August 1948, history was about to unfold and everyone in attendance knew it. A record crowd of seventy-two thousand fans had come to Municipal Park, home of the Cleveland Indians, to witness that history. Those same fans had read in the newspapers or heard on the radio just 16 months earlier about America’s historic moment when Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier on April 15, 1947.

While other Black players had joined the major league since Jackie Robinson, the excitement over tonight’s player, with the exception of Robinson’s debut, trumped them all. The fans had come to see Satchel Paige, arguably the greatest pitcher of his generation, Black or White, and for many who saw him in his heyday would argue, perhaps the greatest of all time.

Paige was about to become the first Black pitcher to start an American League game. Aside from the history-making moment, there was plenty on the line in the present moment, as well. The Indians were in the thick of the 1948 pennant race against the feared Boston Red Sox, led by the legendary Ted Williams. A pennant race that seemed inconceivable just a season ago, the new owner and general manager of the Indians, Bill Veeck, had done much to improve the club in his two years of ownership.

Needing one more elite arm, Veeck signed Paige on July 7, 1948, Satchel’s forty-second birthday. At an age when most players have already retired, Paige was about to become the oldest rookie in baseball history.

The crowd that night on August 3 was electric as they waited to catch a glimpse of this living legend. As he took each step slowly to the mound, the cheers went from a low roar to a deafening thunder. After a few pinpoint accurate warm-up pitches, it was time. The batter stepped to the plate as Satchel Paige was about to realize a dream 22 years in the making. A dream that at no point during those 22 years did he ever think was likely to occur.

Standing nearly six-feet five but weighing less than one hundred eighty pounds, with size 14 shoes and long spindly arms and legs, he did not look like a prototypical athlete. Paige himself would say he looked like an “ostrich.” But whether it was his body type, his natural ability, his fierce determination or some combination of all of those things, Satchel Paige could throw a baseball better than just about anyone who ever tried.

While difficult to prove without accurate record keeping, at twenty-five hundred and two thousand respectively, Paige claims to have pitched in and won more games than anyone else. What’s not difficult to prove is that he pitched more years, in more places, with more teams and more showmanship than anyone else in the history of organized baseball. A career that is even more astounding because for so many of his games, Paige pitched through acute and chronic stomach pains he called ‘the miseries’.

When Paige pitched, it was a must see event. He routinely broke attendance records in every town he visited. His presence on the mound was intimidating. He threw the ball harder and more accurately than anyone had ever witnessed. His windup, high leg kick and torqued delivery struck fear in the heart of the opposing batters or at least the ones who could even see the one hundred mile per hour, precision pitches before they reached the catcher’s mitt.

He was a self-described loner who hid in plain sight. His introversion did not hinder him from pitching in front of millions or becoming one of the greatest showmen the game has ever seen. He played to the crowd for laughs and cheers but always took baseball seriously. He would often talk to the batters telling them exactly what he was going to do and despite that advantage for the hitter it rarely mattered.

Most pitchers have a few pitches they rely on to get them through a game and a career; Paige had a library of them and he named each and every one. His forkball was called the whipsy-dipsy-do, his fastball was called trouble and his bee ball got its name because it would be right where he wanted it, high and inside. He had the blooper, the looper and the drooper. If a batter crowded the plate, he’d throw his barber pitch to brush them back and give them a clean shave. He also had a midnight creeper, a side-armor, a submariner, an ally-oops, a slow gin fizz and many, many more.

Satchel Paige was an almost unexplainable force of nature on and off the field. But his story makes clear that neither his humble beginnings nor a segregated society could prevent his undeniable gifts and spirit from reaching unimaginable heights and affecting history for himself, his teammates and his sport, all for the better.

Leroy Paige was born in the segregated south of Mobile, Alabama on July 7, 1906. This date, while known today, would be a source of confusion and humor for anyone who ever tried to ascertain Paige’s date of birth during his playing days. This is because both Paige and his mother offered dates other than the actual date as did Paige’s friends and anyone else who was asked. Paige who himself offered so many different answers to his own date of birth once remarked, “How old would you be if you didn’t know how old you are?”

At seven, Paige had his first steady job—carrying the bags of arriving train passengers at the local rail depot to nearby hotels. Leroy could only carry one at a time for ten cents a trip, so he grabbed a pole and some rope and created a device balanced over his shoulders that allowed him to carry multiple bags to multiply his income. The other boys at the rail depot teased Paige and said, “You look like a walking satchel tree.” The nickname stuck, and thereafter Leroy Paige would forever be known as Satchel Paige.

At 10 years old, Paige tried out for the elementary school baseball team. At first he played mostly outfield. Then midway through the season, the team got down six to zero in the first inning; so Coach Wilbur Heinz gave Satchel a chance to pitch. He strode to the mound and, despite having never thrown a pitch in a competitive game, struck out the first batter he faced and then struck out the next two. He pitched the rest of the game, eight innings in all. He struck out 16 and didn’t give up a hit. While they didn’t keep meticulous records of Mobile elementary school games, according to Paige he had just thrown his first no-hitter before he reached the fifth grade.

Paige would get his start in organized baseball with the local Mobile Tigers in 1924. His talent at 20 was so evident that he quickly rose through the ranks of the newly formed Negro Leagues. He threw harder and more accurately than anyone had ever seen, resulting in a ridiculous number of strikeouts and losses so infrequent, most couldn’t remember when or if they ever happened.

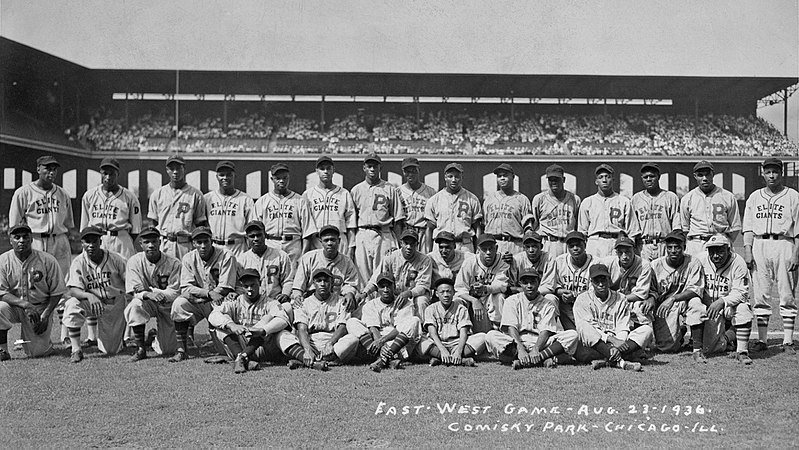

Satchel reached his prime in the 1930s, and along with it national and international fame, as he pitched for the famed Pittsburgh Crawfords. A team that boasted some of the greatest Negro League teams ever-assembled including future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, James “Cool Papa” Bell, Judy Johnson and Jud Wilson.

When Paige wasn’t playing for the Crawfords, or sometimes when he was, he began pitching year-round for just about any team that offered him a paycheck. While his own motivations were largely financial, he had a more profound impact across America and in other countries. Millions witnessed Paige’s talent and personality, but more importantly, those same millions saw that Paige and his teammates were the equal to, and often the better of, some of the best the White major leagues had to offer.

Paige squared off against some of the greatest hitters in the game including Joe DiMaggio who said Paige was the best he ever faced. Paige also faced some of the best major league pitchers. Starting in 1934, Satchel would barnstorm with St. Louis Cardinal Dizzy Dean, who most, including Dean himself, viewed as one of the game’s best. But after witnessing Paige’s talent, Dean was more humble when he said, "I know who's the best pitcher I ever see and it's old Satchel Paige. My fastball looks like a change of pace alongside that little pistol bullet ole Satchel shoots up to the plate."

See also: Sizzling Satchel Paige, by Larry Tye

Throughout the 1940s, Paige pitched for the Kansas City Monarchs, another storied Negro League franchise. Just as in Pittsburgh, Paige played with some of history’s best including future Hall of Famers Hilton Smith, Norman “Turkey” Stearns and in 1945 Jackie Robinson. Jackie and Satchel only played one season together after Branch Rickey signed Robinson to play for the Dodgers, breaking baseball’s long-overdue color barrier in 1947.

A mix of emotions, Satchel was happy that the color barrier would finally be broken but disappointed that he was not the choice. That did not stop him from taking the high road when asked about the signing. “They didn’t make a mistake by signing Robinson,” Satchel said. “They couldn’t have picked a better man.”

Satchel’s own call to the majors would come just one year later when he signed with the Cleveland Indians on July 7, 1948, his 42nd birthday. When he threw his first pitch in relief a few days later, Paige became not only the first Black pitcher in the American League, but also the oldest rookie in major league baseball.

Just a few weeks later, Satchel and all of Cleveland got the moment they were waiting for, Paige’s first start. A record crowd of 72,000 came to witness Paige pitch the Indians to a win and first place. Satchel’s next start was on the road at Comiskey Park in Chicago where he broke their attendance record as the fans were treated to a 42-year old rookie pitching his first shutout. He would repeat the feat just a week later back in Cleveland when he broke his own two-week old attendance record and threw another shutout. Paige’s helped Cleveland win their first pennant and trip to the World Series in twenty-eight years. Satchel appeared in relief in game five and the Indians would win the series in six games.

For the first twenty-two years of his career, Paige was denied an opportunity to showcase his talents in major league baseball. Now, in a three-month span at the age of 42, Satchel could say he was a major league pitcher, had won six of his seven games, had received votes for rookie of the year, had helped his team win the pennant, pitched in a World Series and was a World Series champion. And if all that he accomplished on the field in 1948 wasn’t enough, Satchel and his wife Lahoma welcomed their first child that year, as well.

Satchel Paige’s statistics will remain a mystery to fully account for. Though given his longevity in baseball and the fact that he pitched constantly for more than thirty years and almost every one of the those years at an elite level, it is hard to argue that he doesn’t belong near, or at the very top of, the list of greatest pitchers of all time.

Though what makes him transcendent in the sport and in society was his combination of talent and personality. He was a student and practitioner of the game but also had an innate ability to connect with the fans to make them enjoy the game as much as to be awed by his talent. While his barnstorming had more to do with gainful employment and a love of baseball than breaking color barriers, he did much; perhaps more than any other, to show America and every country he pitched in what was possible. As one veteran of the Negro Leagues put it, “Jackie opened the door, but Satchel inserted key.”