“Now the war has begun and no one knows when it will end,” said one minuteman after the fight.

-

Spring 2025

Volume70Issue2

Editor's Note: Rick Atkinson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and winner of the prestigious George Washington Book Prize for The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777, in which portions of this essay appeared. Mr. Atkinson's most recent book, published this month, is The Fate of the Day The War for America, Fort Ticonderoga to Charleston, 1777-1780, the second book of his trilogy on the Revolution.

By early morning on April 19, 1775, Concord was ready for the redcoats. Paul Revere had been captured by a British mounted patrol at a bend in the road near Folly Pond, but William Dawes managed to escape at a gallop. Continuing his charmed morning, Revere — saucy and unrepentant, even with a pistol clapped to his head — was soon released, though without his brown mare, to make his way on foot to the Clarke parsonage in Lexington. But others had carried warnings into Concord, where a sentinel at the courthouse fired his musket and heaved on the bell rope. The clanging, said to have “the earnestness of speech” and pitched to wake the dead, soon drove all fifteen hundred living souls from their beds.

Reports of the earlier shooting in Lexington “spread like electric fire,” by one account, though some insisted that the British would only load powder charges without bullets. Many families fled west or north, or into a secluded copse called Oaky Bottom, clutching the family Bible and a few place settings of silver while peering back to see if their houses were burning. Others buried their treasures in garden plots or lowered them down a well. Boys herded oxen and milk cows into the swamps, flicking at haunches with their switches.

Militiamen, alone or in clusters or in entire companies with fife and drum, rambled toward Concord, carrying pine torches and bullet pouches, their pockets stuffed with rye bread and cheese. They toted muskets, of course — some dating to the French war, or earlier — but also ancient fowling pieces, dirks, rapiers, sabers hammered from farm tools, and powder in cow horns delicately carved with designs or calligraphic inscriptions, an art form that had begun in Concord decades earlier and spread through the colonies.

Some wore “long stockings with cowhide shoes,” a witness wrote. “The coats and waistcoats were loose and of huge dimensions, with colors as various as the barks of oak, sumac, and other trees of our hills and swamps could make them.” In Acton, six miles to the northwest, nearly forty minutemen gathered at Captain Isaac Davis’s house, polishing bayonets, replacing gunlock flints, and powdering their hair with flour. Davis, a thirty-year-old gunsmith with a beautiful musket, bade good-bye to his wife and four youngsters with a simple, “Hannah, take good care of the children.”

“It seemed as if men came down from the clouds,” another witness recalled. Some took posts on the two bridges spanning the Concord River, which looped west and north of town. Most made for the village green or Wright Tavern, swapping, rumors and awaiting orders from Colonel James Barrett, the militia commander, a sixty-four-year-old miller and veteran of the French war who lived west of town. Dressed in an old coat and a leather apron, Barrett carried a naval cutlass with a plain grip and a straight, heavy blade forged a generation earlier in Birmingham.

Barrett’s men were tailors, shoemakers, smiths, farmers, and keepers from Concord’s nine inns. But the appearance of tidy prosperity was deceiving: Concord was suffering a protracted decline from spent land, declining property values, and an exodus of young people, who had scattered to the frontier in Maine or New Hampshire rather than endure lower living standards than their elders had enjoyed. This economic decay, compounded by the Coercive Acts and British political repression, made these colonial Americans anxious for the future, nostalgic for the past, and, in the moment, angry.

Sometime before eight a.m., perhaps two hundred impatient militiamen headed for Lexington to the rap of drums and the trill of fifes. Twenty minutes later, eight hundred British soldiers hove into view barely a quarter mile away, like a scarlet dragon on the road near the junction known as Meriam’s Corner. “The sun shined on their arms & they made a noble appearance in their red coats,” Thaddeus Blood, a nineteen-year-old minuteman, later testified. “We retreated.”

They fell back in an orderly column, as if leading an enemy parade into Concord, the air vibrant with competing drumbeats. “We marched before them with our drums and fifes going and also the British drums and fifes,” militiaman Amos Barrett recalled. “We had grand music.” Past the meetinghouse the militia marched, past the liberty pole that had been raised as an earnest sign of their beliefs. A brief argument erupted over whether to make a stand in the village — “If we die, let us die here,” urged the militant minister William Emerson — but most favored better ground on the ridgeline a mile north, across the river. Colonel Barrett agreed, and ordered them to make for North Bridge. Concord was given over to the enemy.

The British brigade wound past Abner Wheeler’s farm, and the farms of the widow Keturah Durant and the spinster seamstress Mary Burbeen and then the widow Olive Stow, who had sold much of her land, along with a horse, cows, swine, and salt pork, to pay her husband’s debts when he’d died, three years earlier. They strode past the farms of Olive’s brother, Farwell Jones, and the widow Rebecca Fletcher, whose husband also had died three years before, and the widower George Minot, a teacher with three motherless daughters, who was not presently at home because he was the captain of a Concord minute company. Into largely deserted Concord the regulars marched, in search of feed for the officers’ horses and water for the parched men. From Burial Ground Hill, Colonel Francis Smith and Major John Pitcairn of the Marines studied their hand-drawn map and scanned the terrain with a spyglass.

Gage’s late intelligence was accurate: in recent weeks, most military stores in Concord had been dispersed to nine other villages or into deeper burrows of mud and manure. Regulars seized sixty barrels of flour found in a gristmill and a malt house, smashing them open and powdering the streets. They tossed five hundred pounds of musket balls into a millpond, knocked the trunnions from several iron cannons found in the jail yard, chopped down the liberty pole, and eventually made a bonfire of gun carriage, spare wheels, tent pegs, and a cache of wooden spoons. The blaze briefly spread to the town hall, until extinguished by a bucket brigade of British soldiers and villagers.

With the pickings slim in Concord, Colonel Smith ordered more than two hundred men under Captain Lawrence Parsons to march west toward Colonel Barrett’s farm, two miles across the river. Perhaps they would have better hunting there.

Since 1654, a bridge had spanned the Concord River just north of the village. The current structure, sixteen feet wide and a hundred feet long, had been built for less than £65 in 1760 by twenty-six freemen and two slaves, using blasting powder and five teams of oxen. The timber frame featured eight bents to support the gracefully arcing deck, each with three stout piles wedged into the river bottom. Damage from seasonal floods required frequent repairs, and prudent wagon drivers carefully inspected the planks before crossing. A cobbled causeway traversed the marshy ground west of the river.

Seven British companies crossed the bridge around nine that Wednesday morning, stumping past stands of black ash, beech, and blossoming cherry. Dandelions brightened the roadside, and the soldiers’ faces glistened with sweat. Three companies remained to guard the span, while the other four continued with Captain Parsons to the Barrett farm, where they would again be disappointed: “We did not find so much as we expected,” an ensign acknowledged. A few old gun carriages were dragged from the barn, but searchers failed to spot stores hidden under pine boughs in Spruce Gutter or in garden furrows near the farm’s sawmill.

The five Concord militia companies had taken post on Punkatasset Hill, a gentle but insistent slope half a mile north of the bridge. Two Lincoln companies and two more from Bedford joined them, along with Captain Davis’s minute company from Acton, bringing their numbers to perhaps 450, a preponderance evident to the hundred or so redcoats peering up from the causeway; one uneasy British officer estimated the rebel force at fifteen hundred. On order, the Americans loaded their muskets and rambled downhill to within three hundred yards of the enemy. A militia captain admitted feeling “as solemn as if I was going to church.”

Solemnity turned to fury at the sight of black smoke spiraling above the village: the small pyre of confiscated military supplies was mistaken for British arson. Lieutenant Joseph Hosmer, a hog reeve and furniture maker, was described as “the most dangerous man in Concord” because young men would follow wherever he led. Now Hosmer was ready to lead them back across the bridge. “Will you let them burn the town down?” he cried.

Colonel Barrett agreed. They had waited long enough. Captain Davis was ordered to move his Acton minutemen to the head of the column — “I haven’t a man who’s afraid to go,” Davis replied — followed by the two Concord minute companies; their bayonets would help repel any British counterattack. The column surged forward in two files. Some later claimed that fifers tootled “The White Cockade,” a Scottish dance air celebrating the Jacobite uprising against the British of 1745. Others recalled only silence but for footfall and Barrett’s command “not to fire first.” The militia, a British soldier reported, advanced “with the greatest regularity.”

Captain Walter Laurie, commanding the three light infantry companies, ordered his men to scramble back to the east side of the bridge and into “street-firing” positions, a complex formation designed for a constricted field of fire. Confusion followed, as a stranger again commanded strangers. Some redcoats braced themselves near the abutments. Others spilled into an adjacent field or tried to pull up planks from the bridge deck.

Without orders, a British soldier fired into the river. The white splash rose as if from a thrown stone. More shots followed, a spatter of musketry that built into a ragged volley. Much of the British fire flew high — common among nervous or ill-trained troops — but not all. Captain Davis of Acton pitched over dead, blood from a gaping chest wound spattering the men next to him. Private Abner Hosmer also fell dead, killed by a ball that hit below his left eye and blew through the back of his neck.

Three others were wounded, including a young fifer and Private Joshua Brooks of Lincoln, grazed in the forehead so cleanly that another private concluded that the British, improbably, were “firing jackknives.” Others knew better.

Captain David Brown, who lived with his wife, Abigail, and ten children two hundred yards uphill from the bridge, shouted, “God damn them, they are firing balls! Fire, men, fire!” The cry became an echo, sweeping the ranks: “Fire! For God’s sake, fire!” The crash of muskets rose to a roar.

“A general popping from them ensued,” Captain Laurie later told General Gage. One of his lieutenants had reloaded when a bullet slammed into his chest, spinning him around. Three other lieutenants were wounded in quick succession, making casualties of half the British officers at the bridge and ending Laurie’s fragile control over his detachment.

Redcoats began leaking to the rear, and soon all three companies broke toward Concord, abandoning some of their wounded. “We was obliged to give way,” an ensign acknowledged, “then run with the greatest precipitance.” Amos Barrett reported that the British were “running and hobbling about, looking back to see if we was after them.” Battle smoke draped the river. Three minutes of gunplay had cost five American casualties, including two dead. For the British, eight were wounded and two killed, but another badly hurt soldier, trying to regain his feet, was mortally insulted by minuteman Ammi White, who crushed his skull with a hatchet.

A peculiar quiet descended over what the poet James Russell Lowell would call “that era-parting bridge,” across which the old world passed into the new. Some militiamen began to pursue the fleeing British into Concord, but then veered from the road to shelter behind a stone wall. Most wandered back toward Punkatasset Hill, bearing the corpses of Davis and Abner Hosmer. “After the fire,” a private recalled, “everyone appeared to be his own commander.”

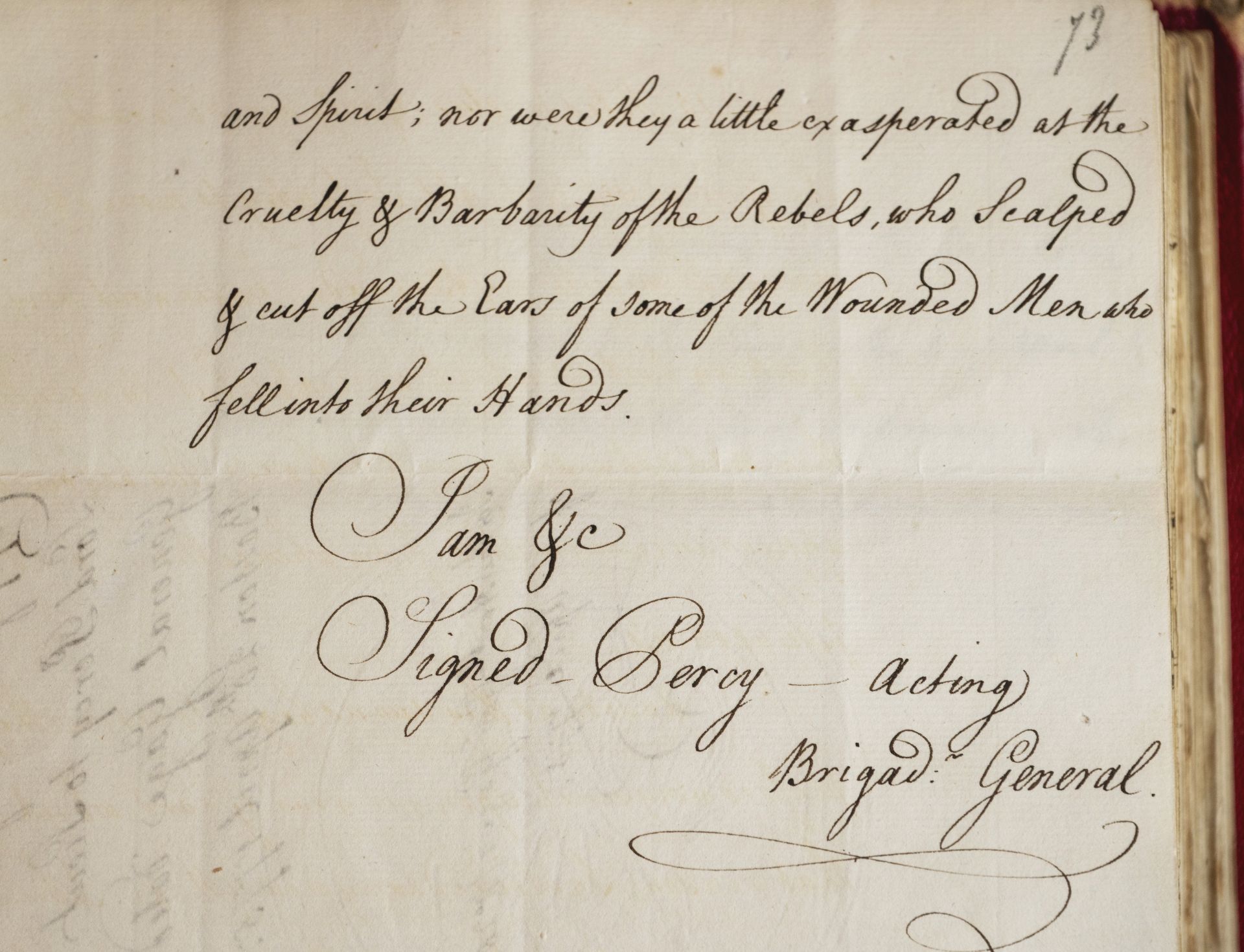

Colonel Smith had started toward the river with grenadier reinforcements, then thought better of it and trooped back into Concord. The four companies previously sent with Captain Parsons to Barrett’s farm now trotted unhindered across the bridge, only to find the dying comrade mutilated by White’s ax, his brains uncapped. The atrocity grew in the retelling: soon enraged British soldiers claimed that he and others had been scalped, their noses and ears sliced off, their eyes gouged out.

As Noah Parkhurst from Lincoln observed moments after the shooting stopped, “Now the war has begun and no one knows when it will end.”