An estimated 1500 privateering ships played a crucial role in winning the American Revolution, but their contributions are often forgotten.

-

Summer 2022

Volume67Issue3

Editor’s Note: One of today’s finest writers about ships and the sea, Eric Jay Dolin previously contributed “Did Hurricanes Save America?” to American Heritage, which focused on the impact of deadly weather on the American Revolution. His latest book, Rebels at Sea: Privateering in the American Revolution, is a fascinating look at the role played by privateers in winning independence. We asked Mr. Dolin to give us an overview of the important and neglected contribution of privateers to our history.

A tall, angular man with a Roman nose and a cool demeanor stood on the quarterdeck of the American privateer Pickering, peering through a spyglass at a strange ship in the distance. It was late in the day on June 3, 1780, and Captain Jonathan Haraden was approaching the friendly port of Bilbao, Spain, where the Pickering had been expecting to sell goods and resupply. However, the ship, a fast-rigged lugger, stood in the way.

A captured British officer on board the Pickering, Robert Scott, informed Haraden that the ship in the distance was the British privateer Achilles with 130 men and 43 cannon, mostly nine- and eighteen-pounders. Scott claimed the lugger was “the largest of its kind that had ever been fitted out from Great Britain.” In contrast, Haraden’s Pickering had only 38 crew and 16 little six-pounder cannon. Scott assumed the American would try to escape.

But Haraden relished the chance to confront the enemy and strike a blow for the revolutionary cause. Turning to Scott, Haraden calmly said, “I shan’t run from her.”

As the sky turned overcast and night darker, Haraden surmised that Achilles would put off its attack until morning. He retired to his cabin, ordering the watch to keep a sharp eye on the enemy ship and wake him should it approach. As dawn broke, the Achilles began its advance, and a crewman rushed to alert Haraden. He “calmly rose and went up on deck, as if it had been some ordinary occasion,” and surveyed his ship to make sure his men were prepared for the confrontation.

Haraden assembled his crew and told them that “though the lugger appeared to be superior to them in force, he had no doubt that they should beat her off if they were firm and steady, and did not throw away their fire.” Soon booming broadsides and a staccato of musket fire filled the air, as the vessels engaged in their deadly dance, each trying to gain the upper hand.

Robert Cowan, one of Haraden’s crew, later remarked that the Pickering “looked like a longboat by the side of” the Achilles. He added that Haraden “fought with an energy and determination that seemed superhuman,” and that while “shot flew around him” he was “as calm and steady as amidst a shower of snowflakes.”

The battle raged for more than two hours, with no clear advantage on either side. Then, Haraden ordered his men to fill the cannons with bar shot — two iron balls or hemispheres connected by a solid rod. These projectiles, violently spinning as they flew through the air, were devastating, slashing through the Achilles’ rigging and sails. Having had enough, the Achilles turned and fled. Haraden brought his ship into Bilbao harbor to a hero’s welcome from the crowd that had watched the fight offshore.

As captain of Pickering from the fall of 1778 to 1780, Haraden took numerous prizes. A particularly spectacular success came in October 1779 off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, when he came upon three British privateers, armed with fourteen, ten, and eight cannons, respectively. One of Haraden’s officers, “though a brave man, advised him not to engage them as it would be imprudent, on account of their force.” Haraden evenly replied that the officer was free to go below, but with or without him, he was going to do “his duty” and attack.

In an engagement lasting one and a half hours, the Pickering captured all three ships. The speed with which Haraden accomplished this feat was a function of his fighting style. As one of his crewmen said, Haraden liked to “go alongside, and do what was to be done in a short time.”

During the Revolution, Haraden took many prizes and brought back hundreds of British cannon and military supplies crucial to the American cause. Born in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1745, he was sent to Salem as a boy to apprentice as a cooper. Haraden must have gained experience at sea in the years leading up to the American Revolution, because in June 1776 he was commissioned as first lieutenant on the aptly named sloop Tyrannicide, which Massachusetts sent out as part of its colonial (soon to be state) navy. The idea was to protect its merchantmen and seize British ones.

As first lieutenant and later captain of the Tyrannicide, Haraden did just that, earning the respect of the Massachusetts Board of War, which called him a “brave officer” who “always acquitted himself with spirit and honor.” Disagreements over pay, however, led him to leave the Massachusetts navy and become a privateersman.

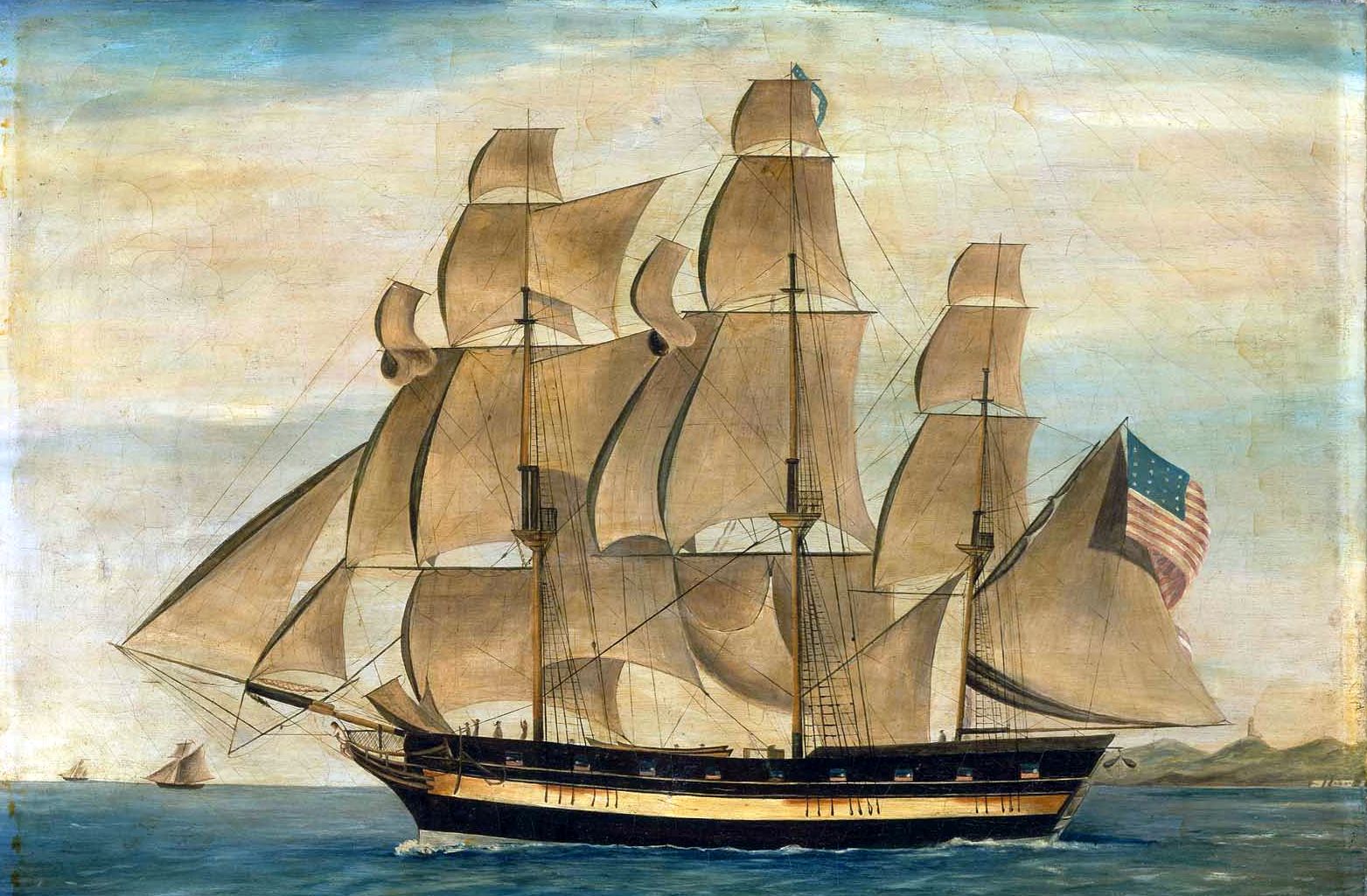

When Haraden took command of Pickering on September 30, 1778, it was one of more than a thousand American privateers, and he was one of tens of thousands of privateersmen who served during the American Revolution. (Often both the vessels and the men who served on them are called “privateers.” Because that can lead to confusion, the vessels are usually referred to as “privateers” and the men sailing them “privateersmen.”)

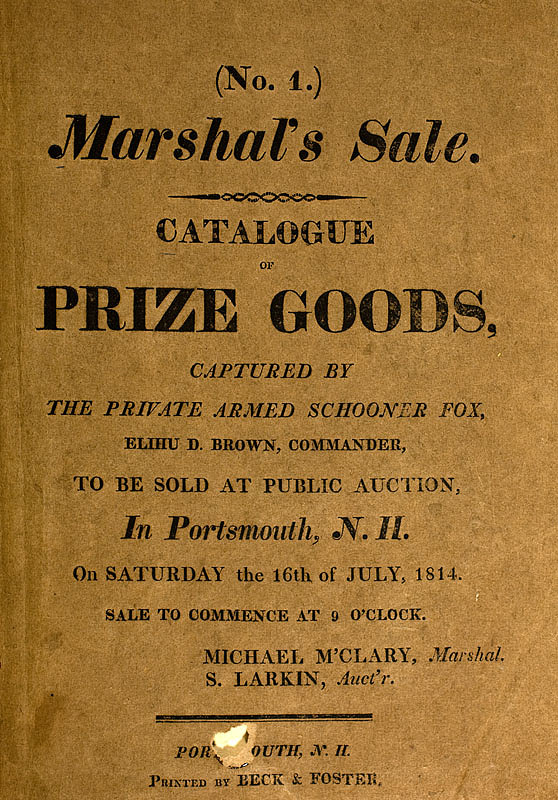

Privateers were armed vessels owned and outfitted by private individuals who had government permission to capture enemy ships in times of war. That permission came in the form of a letter of marque, a formal legal document issued by the government that gave the bearer the right to seize vessels belonging to belligerent nations and to claim those vessels and their cargoes, or prizes, as spoils of war. The proceeds from the auction of these prizes were in turn split between the men who crewed the privateers and the owners of the ship.

Typically, governments used privateers to amplify their power on the seas, most notably when their navies were not large enough to effectively wage war. More specifically, by attacking the enemy’s maritime commerce and, when possible, its naval forces, privateers could inflict significant economic and military pain at no expense to the government that commissioned them. Privateers were like a cost-free navy. One late nineteenth-century historian dubbed them “the militia of the sea.”

There were two types of privateers. Some were heavily armed with large crews, their sole purpose to seek out and capture enemy ships. The large crew was needed to work the cannons and fight enemy sailors and marines with muskets and swords but also to man the newly acquired prizes and sail them back to port — while allowing the privateer to continue on, now with a smaller but still sufficient crew, searching for the next prey. Other privateers like Haraden’s Pickering were primarily merchant vessels intent on trade; these traveled between ports to buy and sell goods but also had permission to attack enemy shipping, and would do so when the opportunity arose. This latter type of privateer was often referred to as a “letter of marque” — not to be confused with the authority described above — whereas the first type of privateer was called just that, a privateer.

Because the letter of marque’s main purpose was trade, it generally had fewer cannons and a smaller crew than a conventional privateer, although it usually took along enough crewmen to man a few prizes. One other crucial difference concerned pay. While the crews of privateers earned money only if they took prizes, those on letters of marque were paid a base salary, which was supplemented by any prize money they earned. Privateers brought in the vast majority of the prizes during the Revolution, as compared to letters of marque. Some vessels alternated between the two statuses.

Despite the contributions made by Haraden and thousands of other privateersmen during the Revolution, many believed then and have believed since that privateering was a sideshow in the war. Privateering has long been given short shrift in general histories of the conflict, where privateers are treated as a minor theme if they are mentioned at all. The coverage in maritime and naval histories of the Revolution is not much better, with privateering often overshadowed by the exploits of the Continental navy.

As John Lehman, former secretary of the navy under President Ronald Reagan, observed, “From the beginning of the American Revolution until the end of the War of 1812, America’s real naval advantage lay in its privateers. It has been said that the battles of the American Revolution were fought on land, and independence was won at sea. For this we have the enormous success of American privateers to thank even more than the Continental Navy.” Yet even in the face of plenty of readily available evidence, “the official canon of naval history in both Britain and the United States virtually ignores” privateers.

The fact is, privateering was critical to winning the war. American privateersmen took the maritime fight to the British and made them bleed. In countless daring actions against British merchant ships and not a few warships, privateers caused British maritime insurance rates to precipitously rise, diverted critical British resources and naval assets to protecting their vessels and to attacking privateers, added to British weariness over the war, and played a starring role in bringing France into the war on the side of the United States, a key turning point in the conflict.

On the domestic front, privateering brought much-needed goods and military supplies into the new nation, provided cash infusions for the war effort, boosted coastal economies through the building, outfitting, and manning of privateers, and bolstered America’s confidence that it might succeed in its seemingly quixotic attempt to defeat the most powerful military force of the day.

Critics of privateering have admitted its influence but characterized that influence as largely negative, if not deleterious. These claims come mainly from those who blame privateering for siphoning valuable manpower and munitions from the Continental navy and army and for contributing to a coarsening of American morals and republican ideals by purportedly offering a means for men to place profit over patriotism. But such arguments lose much of their sting and persuasive power when considered within the actual context of the war. And whatever drawbacks came with privateering, they pale in comparison to its positive contribution to the Revolution.

The importance of privateering can only be grasped when the practice is set against the precarious nature of the war. At the outset, there were few reasons for the rebellious colonies to be confident of a good outcome. As William Moultrie, South Carolina’s most famous Revolutionary War hero, would write years after the conflict, Americans were rising up against “a rich and powerful nation, with numerous fleets, and experienced admirals sailing triumphant over the ocean; with large armies and able generals in many parts of the globe: This great nation we dared to oppose, without money; without arms; without ammunition; no generals; no armies; no admirals; and no fleets; this was our situation when the contest began.”

Every year of the Revolution, there was cause to doubt that the colonies would be able to hold on, much less win. George Washington later reflected that the American victory in the war “was little short of a standing miracle.” At many points during the Revolution, the war might have ended in American defeat had different decisions been made or different actions taken, and had various elements not been in place. Yet throughout, privateering provided a source of strength that helped the rebels persevere.

Although privateering was not the single, decisive factor in beating the British — there was no one cause — it was extremely important nonetheless. The exact number of privateers and privateersmen who operated during the Revolution is unknowable, but the figures we do have suggest that they were pivotal to the war. Records are incomplete and often duplicative — many were logged both at the congressional and state level.

Further complicating any attempt to arrive at reliable figures is that contemporary accounts often applied the term “privateer” to vessels that were most certainly not privateers. As a result, many Continental navy vessels as well as state navy vessels were incorrectly labeled as privateers in newspapers, letters, and official government documents printed during or just after the Revolution.

Some historians have perpetuated the error. Haraden’s sloop Tyrannicide, which was a Massachusetts navy vessel, is frequently called a privateer in modern accounts, for example.

The best single source of basic facts on privateering during the war is the Library of Congress’s Naval Records of the American Revolution. It lists 1697 armed vessels that received letters of marque from the Continental Congress and which were manned by 58,400 men and carried 14,872 cannons. Yet these numbers cannot be taken at face value. Quite a few of the listed vessels received multiple letters of marque, for different cruises in different years, and thus were double- or triple-counted; many men served on more than one privateer; and a considerable portion of the cannons saw service on more than one ship as well.

Also, a few states, notably Massachusetts and New Hampshire, issued their own letters of marque independent of Congress, and it is not clear exactly how many of these state privateers there were. Some sources claim the number was relatively low, perhaps around one hundred, while others say that there was as many as one thousand. Although the overall number of privateers cannot be precisely known, it was large, and most likely within a few hundred of 1697.

In a common misconception, many observers before, during, and since the Revolution have argued that privateersmen were virtually indistinguishable from pirates. The historian Barbara Tuchman wrote that “privateers were essentially ships with a license to rob.”

But while there might be truth in this, particularly with respect to earlier periods of history, it doesn’t apply to privateering during the American Revolution. By that time, laws had been better codified, government oversight of the practice was more effective, and legitimate privateersmen had less incentive to veer into piracy. Privateersmen operating during the American Revolution were not pirates, and the vast majority acted honorably, observing international law and the laws and regulations laid down by the Continental Congress during the war. The few exceptions only served to prove the rule.