Interest in the outlaw has grown recently with the discovery of the first authenticated photographs of Henry McCarty, who died in 1881 at the age of 21 after a short, notorious life of gambling and gunfights.

-

Spring 2018

Volume63Issue1

It took just two minutes and thirty seconds. In June 2011, close to 500 people attended a public auction in Denver, Colorado, to witness an iconic tintype go on the block. The auction house had published a presale estimate of $300,000–$400,000, a jaw-dropping price for any historic photograph.

When the bidding for Lot 279 finally began, the rapid-fire chatter of the auctioneer electrified a room already tense with anticipation. Spectators cranked their heads and twisted in their seats to see who was bidding in $100,000 increments. And when the hammer fell—for a record $2.3 million dollars—a roar erupted from the crowd, followed by near pandemonium. Reporters, photographers, onlookers with camera phones mobbed the winning bidder: billionaire William I. Koch.

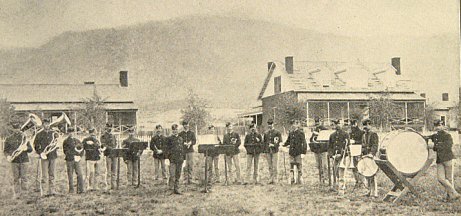

What Koch had purchased was smaller than a credit card, but the slightly hazy image staring out of the thin metal sheet was of a living, breathing Billy the Kid, taken 130 years ago at Fort Sumner in the New Mexico Territory. At that time the Kid already had several killings to his name, including a sheriff and a deputy. He himself would be gunned down not much more than a year later, but his most infamous exploits, and arguably his most heinous killings, still lay ahead.

His real name was Henry McCarty. In fact, he didn’t acquire his distinctive moniker until the last six months of his short life. He said more than once that he was born in New York City. No one knows for sure if that is true, nor the exact year of his birth, but 1859 seems the most likely. We do know that he was living with his widowed mother, Catherine, and brother, Joseph, in Indianapolis in the late 1860s. From there, the family hopscotched to Wichita, Denver, and Santa Fe, where in 1873 Catherine married her lover, William Antrim, an Indiana Civil War veteran. Among the names of witnesses scrawled on their Santa Fe marriage record is that of Henry McCarty.

Within the year the family relocated again, this time to Silver City, a mining boomtown near the continental divide in southwest New Mexico. Young Henry attended school for a short time, but the town’s busy streets, saloons, and dance halls were more to his liking, and after Catherine succumbed to tuberculosis in 1874, he proceeded to make a nuisance of himself. William Antrim, far more interested in striking it rich than in looking after his stepsons, essentially abandoned them. When Henry got caught with stolen goods from the robbery of a Chinese laundry, the sheriff threw him in jail.

Most accounts say that the sheriff simply wanted to teach 15-year-old Henry a lesson. Henry did learn a lesson—that he could fit his small frame through a sooty chimney flue. With the first of several incredible escapes, he hightailed it for southern Arizona, where he became known as Kid Antrim or simply “the Kid.” There he got into more trouble stealing horses from the U.S. Army, but his biggest problem was a bully named “Windy” Cahill. Cahill, a blacksmith at Camp Grant, took sick delight in roughing up the Kid. That is, until the Kid decided he’d had enough and shot Cahill through the belly with a newly acquired six-gun. The Kid didn’t stick around to see Cahill die but grabbed a pony and fled to New Mexico’s Lincoln County.

The largest county in the United States at that time, Lincoln’s nearly 30,000 square miles was primarily cattle country, but there was big money in obtaining government contracts to supply beef, corn, flour, and other provisions to the military post of Fort Stanton. For years a firm called “the House” controlled those contracts, along with just about every other way to turn a dollar in the region.

That changed when a couple of upstarts challenged the House’s monopoly. They were Englishman John Henry Tunstall and Scotsman Alexander McSween, with backing from storied cattleman John S. Chisum. The fact that Tunstall was an upper-class English Protestant, while the House partners were Irish Catholic, only added fuel to the simmering fire.

In December 1877, Billy, now going by the alias William H. Bonney, found himself once again in jail, this time for the theft of a pair of Tunstall’s horses. But the Englishman surprised the Kid by offering him a job on his ranch. Men handy with a gun were in high demand in Lincoln County, no questions asked.

Hollywood invariably paints Tunstall as an elderly father figure to young Billy, yet Tunstall was only six years his senior. Nevertheless, it is true that the two became close. “Tunstall was the best friend he had,” recalled one of Billy’s pals. After a posse led by Sheriff William Brady—a tool of the House—murdered Tunstall, Billy vowed, “I’ll get some of them before I die.” It was the beginning of the Lincoln County War.

Read about places you can visit that are associated with Billy the Kid, written for American Heritage by Robert Utley, former historian of the National Parks.

Billy and other Tunstall-McSween men formed a group called the Regulators to hunt down Tunstall’s killers. The Regulators began as a legal posse, deputized by the justice of the peace. The men they sought, however, always ended up dead. On April Fools’ Day 1878, Billy and the Regulators ambushed Brady and Deputy George Hindman as they walked down the main street of Lincoln, the county seat. The lawmen collapsed, riddled with bullets. A grand jury indicted Billy for murder.

Three months later, the Lincoln County War ended in a showdown. House gunmen, bolstered by soldiers from Fort Stanton, surrounded McSween and Billy and several Regulators in McSween’s Lincoln home and set it on fire. McSween was shot fleeing the burning building; Billy and the others managed to escape.

Billy was momentarily free, but with a murder indictment hanging over his head, he had few options. The territorial governor, Lew Wallace, appointed to put an end to the violence in Lincoln County, seemed to offer him an out. Wallace desperately wanted to convict the murderers of a Lincoln attorney, and Billy had witnessed the killing. In a secret meeting, Wallace promised Billy a pardon for his testimony. The governor would later claim there was an additional condition: the Kid had to lead “a different life.”

At great personal risk, Billy testified before the grand jury. Weeks later, with no indication the governor planned to make good on their deal anytime soon, Billy slipped out of town. He made his headquarters in Fort Sumner, a small settlement on the Pecos River 130 miles from Lincoln. Perhaps it was impossible for Billy to lead “a different life” even if he wanted to, but there is no indication that he tried. His days and nights were filled with gambling, women, and thieving.

There were many at Fort Sumner, especially among the Hispanic population, who liked him. They called him Billito or el cs. He spoke fluent New Mexican Spanish and could dance the fandango as well as any vaquero. Although he did not have an imposing figure—standing 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighing about 140 pounds—he was good looking. A newspaper reporter described him as having “a frank open countenance, looking like a school boy, with the traditional silky fuzz on his upper lip; clear blue eyes, with a roguish snap about them; [and] light hair and complexion.” Billy’s only “imperfection,” the reporter continued, were “two prominent teeth slightly protruding like squirrel’s teeth.” But no one would have really noticed the teeth if Billy hadn’t smiled so much—when he wasn’t endlessly whistling a tune.

The cattlemen of New Mexico and Texas, on the other hand, were less than charmed by the rustling activities of Billy and the ne’er-do-wells who had now gathered around him. What was needed was a new sheriff, one with grit who wouldn’t hesitate to go after the outlaws. The cattlemen found their man in former buffalo hunter and storekeeper Pat Garrett, an acquaintance—but not a friend—of Billy’s at Fort Sumner.

During the fierce winter of 1880-1, the 6-foot-4 Garrett conducted one of the West’s greatest manhunts, tracking down and capturing the Kid and three of his gang. Temporarily jailed in Santa Fe, the Kid penned a number of letters to Governor Wallace. “I expect you have forgotten what you promised me, this month two years ago,” Billy wrote on March 4, 1881, “but I have not…I have done everything that I promised you I would, and you have done nothing that you promised me.” Billy had a point, but his letters went unanswered.

On April 9, a jury pronounced Billy guilty of the murder of William Brady. Sheriff Garrett was ordered to arrange the Kid’s hanging, set for Friday, May 13. On that unlucky day, it seemed, the Kid’s luck would finally run out. The only one who didn’t think so was Billy, and on April 28, while Garrett was out of town, he surprised and viciously killed his two guards—with their own guns.

Before calmly riding out of town—unmolested by the locals—the Kid threatened the lives of Wallace and Garrett. He then disappeared into the foothills of the Capitan Mountains. “When he rode off he went at a walk,” wrote an eyewitness, “and every act, from beginning to end, seemed to have been planned and executed with the coolest deliberation.”

Garrett figured the Kid would cross the border into Mexico. Governor Wallace offered a $500 reward for his capture. But soon there were rumors that Billy had returned to Fort Sumner. The Kid had a sweetheart there, Paulita Maxwell, the sister of the settlement’s leading citizen, Pete Maxwell. Garrett found the rumors hard to believe, but the stories wouldn’t go away.

On the moonlit evening of July 14, the sheriff slipped into Fort Sumner with two deputies and went to see Maxwell, who he knew well. Garrett left the deputies outside with the horses and entered the big ranch house. About midnight, as he sat on the side of Pete Maxwell’s bed asking the rancher about Billy’s whereabouts, the Kid burst through the open doorway, a gun in one hand and a butcher knife in the other. “Pete, who are those fellows outside?” Billy asked. At the same moment, the Kid saw the shadowy figure sitting on the bed and pointed his revolver at Garrett.

“¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?” (Who is it? Who is it?), the Kid shouted.

Recognizing Billy’s voice, Garrett quickly drew his .44 revolver and fired two shots as he lunged out of the room. Only the first shot hit Billy, but that was all it took. The bullet punched through the outlaw’s chest just above his heart, knocking him to the floor. There was a groan and some gurgling sounds and then silence. Billy the Kid was dead.

Newspapers across the nation reported the sensational news of the Kid’s death, as did the London Times. But Billy and his often exaggerated feats—one report claimed that he had “perhaps killed more men than any man of his age in the world”—faded from the American consciousness. He didn’t become a popular subject in dime novels; fewer than a dozen are known to have featured the outlaw. Perhaps publishers found little appeal in a teenage mass murderer, as he was usually depicted in the press. By contrast, Jesse James, much more the professional criminal, figured in scores of pulp novels.

Pat Garrett, with the help of a ghostwriter, rushed his own account of the Kid’s life into print. Garrett mostly wanted to refute the wild tales surrounding the Kid and defend the manner in which he had gunned down the outlaw—some felt Garrett should have given Billy a chance to kill him. “What sort of ‘square fight,’ or ‘even show,’ would I have got,” Garrett countered, “had one of the Kid’s friends in Fort Sumner chanced to see me and informed him of my presence there, and at Pete Maxwell’s room on that fatal night?”

Published in March 1882, Garrett’s The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid contained quite a few wild tales of its own regarding Billy’s exploits, but it sold poorly. Part of the problem was its Santa Fe publisher, who lacked the experience and wherewithal to market the book nationally. In fact, the 128-page volume is so rare today that a crisp copy of the first edition can sell for $20,000 or more.

Over the next four decades, Billy would inspire an occasional newspaper story or a magazine article, but it would take a former Chicago journalist to send the Kid’s legend into the pop-culture stratosphere. In 1926, Doubleday, Page & Co. published Walter Noble Burns’s The Saga of Billy the Kid. In vivid prose, Burns spun an enthralling, if not entirely accurate, tale that became a tremendous bestseller. The newly inaugurated Book of the Month Club chose the volume as its first selection.

“Nothing excited him,” Burns tells us in a passage describing the Kid. “He had nerve but no nerves. He retained a cool, unruffled poise in the most thrilling crisis. With death seemingly inevitable, his face remained calm; his steady hands gave no hint of quickened pulses; no unusual flash in his eyes—and eyes are accounted the Judas Iscariots of the soul—betrayed his emotions or his plans.” Burns’s Billy was Clint Eastwood long before Clint Eastwood was cool.

The book went through multiple printings (it’s still in print today) and was read by everyone from schoolmarms to ministers to Depression-era “public enemies.” After Bonnie and Clyde were shot to death in a horrific ambush on May 23, 1934, a copy of The Saga of Billy the Kid was found in the backseat of their blood-splattered car.

Burns’ Saga was the inspiration for the first commercial song about the outlaw: Andrew “Blind Andy” Jenkins’s “Billy the Kid,” recorded in 1927 by Vernon Dalhart. It also served as the basis of the 1930 film Billy the Kid, directed by King Vidor and starring Johnny Mack Brown in the title role. Eight years later, Aaron Copland’s ballet, Billy the Kid, featuring a dancing, dudeish outlaw with black-and-white-striped trousers, debuted to popular and critical acclaim.

With the growing popularity of the Billy the Kid story, tourists began showing up in New Mexico’s Lincoln County and at Billy’s Fort Sumner grave. Billy’s surviving friends and former Regulators became minor celebrities. In 1938, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) granted $8,657 to restore the old Lincoln County courthouse, where Billy had made his last escape. The New Mexico legislature wanted the federal government to designate the courthouse as a national monument, but critics complained that such an act would immortalize a cold-blooded killer. No matter; the New Mexico governor dedicated it as a state monument the following year in a special ceremony attended by a thousand people, including a few who had known the Kid.

Billy the Kid continued to gallop across the popular imagination and today is an international icon and, for many, a bona fide folk hero. No less than 60 films have been made featuring Billy in some guise. He has been played by Roy Rogers, Paul Newman, Kris Kristofferson, Val Kilmer, Emilio Estevez, and a host of other actors. Hundreds of books have been written about him, including works by novelists such as Michael Ondaatje, N. Scott Momaday, and Larry McMurtry. Bob Dylan, John Hartford, Charlie Daniels, Jon Bon Jovi, and other musicians have written songs about him.

In December 2010, New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson toyed with the idea of issuing a posthumous pardon to Billy. It was one of the biggest news stories of the year—Billy’s portrait appeared on the front page of the Wall Street Journal. The interest was so intense that the governor announced his final decision live to a national audience on ABC’s “Good Morning America.” In case you missed it, Billy did not get his pardon—again.

“I don’t blame you for writing of me as you have,” Billy once told a newspaperman. “You had to believe others’ stories….” And there are so many stories. The Kid did not kill 21 men, one for each year of his life. It was four, single-handedly, and five or six more with the help of others. And he did not survive the night of July 14 at Fort Sumner, despite tales to the contrary. But it is the stories that make legends. When William Koch spent $2.3 million on that timeworn tintype, he was buying physical proof of what has become one of America’s best-known legends.

Yet Billy the Kid, or el Chivato, or Kid Antrim, or Henry McCarty remains, in some ways, as elusive today as when he rode among the pinon pines and yuccas of New Mexico, whistling his favorite tunes. He continues to fascinate us as much for what we don’t know about him as for what we do. No matter how long we gaze upon his frozen image, the buckteeth, the squinty snake eyes, that goofy hat, we can never truly know him. And that may be Billy the Kid’s greatest escape.