Artifacts pulled from the wreck of Blackbeard's flagship Queen Anne's Revenge offer a glimpse into the bloody decades of the early 18th century, when pirates ruled the Carolina coast.

-

Spring 2011

Volume61Issue1

Blackbeard, alias Captain Edward Thatch, in a rare contemporaneous rendering from Captain Charles Johnson's 1724 A History of the Pyrates, blockaded Charles Town (present day Charleston) for two weeks in March 1718, ransoming some of its prominent citizens.

One bright June day in 1718, a handful of fishermen off the coast of North Carolina were startled to see four vessels—a large heavily armed ship and three sloops—running before a freshening southwest breeze under a black banner emblazoned with a skeleton and a bright red bleeding heart. So the rumor was true: Blackbeard’s pirates were bearing on the inlet straight toward their village of Beaufort. The sloops carefully negotiated the hazardous shoals in single file, but their heavier flagship, Queen Anne’s Revenge, grounded on the bar, her sails flapping as the sheets were eased. The sloop Adventure, commanded by Israel Hands, cautiously tacked back down the inlet while Queen Anne’s Revenge’s crew set a kedge anchor astern in an unsuccessful effort to warp her off. Soon Adventure was hard aground too.

As afternoon faded into dusk, Queen Anne’s Revenge rolled aport, sending cannon through her bulwarks into the sea. The pirates, laden with belongings and loot, plunged into small boats or clung to planks, spars, kegs, and barrels. The burdened boats labored through the choppy inlet; those floating were either picked up or swept into the harbor by the surging tide. By nightfall the listing wrecks were abandoned to the rising wind and sea. Over the summer and fall the villagers salvaged what they could before nor’easters and hurricanes broke them up.

Blackbeard, who had served England as a privateer during Queen Anne’s War (1701–13), had arrived in North Carolina with Major Stede Bonnet, a gentleman pirate from Barbados, in the latest flaring of piracy from the West Indies. For centuries European nations had augmented their navies with privateers licensed to prey on enemy merchant vessels in time of war. When peace treaties eliminated the need for privateers, thousands would cross the narrow line back into piracy, heading for Nassau in the Bahamas, a weakly held dependency of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina. The open criminality of this new stronghold forced the British Crown to assert control by sending longtime privateer and famed navigator Captain Woodes Rogers to become the colony’s first royal governor. Rogers arrived with an offer of a royal pardon, the Act of Grace, for those who would submit, just months after Blackbeard and Bonnet had left on their latest foray.

The pirates plundered the French ship, taking 125 slaves.

That previous fall, Blackbeard and Bonnet had been cruising 100 miles east of Martinique when they encountered Captain Pierre Dosset and his 200-ton French frigate La Concorde, nine months out from Nantes and carrying more than 500 slaves from the Guinea coast of West Africa, along with stores of cocoa, copper, and gold dust. Scurvy and dysentery had thinned the 75-man crew, leaving too few able bodies to defend the ship.

The two pirate craft closed swiftly. Once in range, the pirates unleashed two salvos of cannon and a storm of musketry: La Concorde hove to, soon to be overrun by a horde of freebooters, a tall bearded figure at their head. The pirates plundered the French ship, taking 125 slaves and terrorizing the officers into revealing the whereabouts of the gold dust. Blackbeard left them a sloop, the majority of the slaves, and enough food to keep them until they reached Martinique.

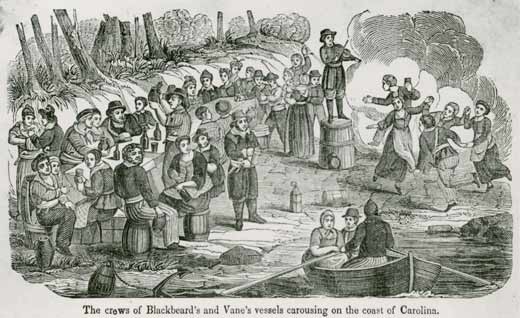

The sound of Blackbeard's Spanish watch bell proved welcome music to many Carolina colonists who had been buffeted by internal dissension and weakened by bloody conflict with the Tuscarora Indians. The pirates brought opportunity for revelry, as illustrated in this 1837 engraving.

In honor of the late Stuart monarch whom he had nominally served, Blackbeard named his new command Queen Anne’s Revenge, a gibe at the new, unpopular Hanoverian King George I. With a weightier armament of as many as 40 guns, his new flagship was as powerful as any Royal Navy warship in the hemisphere. Blackbeard, accompanied by Bonnet’s Revenge, embarked on a destructive campaign, capturing and looting more than 40 prizes from the Leeward Islands to the Virgins. By March 1718, the pirate captains had left the Spanish Main and sailed lazily north in a potent flotilla of three sloops and a frigate, altogether mounting at least 60 guns and crewed by more than 300 pirates, which overmatched the few Royal Navy vessels deployed at sea from the West Indies to North America.

Two months later the people of Charles Town, South Carolina, awoke to “a great Terror”—Blackbeard’s squadron off their harbor. For a week the pirates held up incoming vessels, garnering supplies and nearly £1,500 in gold and silver. The ransom that Blackbeard demanded for his prisoners was a medicine chest worth only £400, but drugs were hard to come by, and the pirates suffered from numerous maladies including syphilis. When the governor proved obstinate, Blackbeard’s threats to behead the hostages had quick effect.

About a month later, the reivers made their rendezvous with disaster at Topsail (now Beaufort) Inlet. Apparently, most (if not all) of the crewmen were rescued by Bonnet’s Revenge and the other remaining sloops and landed at Beaufort village. Bonnet left immediately for the colony’s capital, Bath, to seek the governor’s pardon. Blackbeard took command of the other sloop, armed it, and named it Adventure. Marooning some of his men on a desolate island nearby, Blackbeard sailed toward Bath, taking on 40 crewmen, 60 blacks, and nearly all the loot. Whether as volunteers or pressed men, pirates signed articles that governed their democratically organized communities and specified equitable division of the spoils. Blackbeard’s actions aroused suspicions among his former companions that he had purposely grounded his vessels to reduce the number of shares. This may not have been the case. Although Blackbeard was a skilled seaman, the North Carolina coast was notoriously treacherous, and there is no evidence that he was familiar with Topsail Inlet.

The pirates had arrived at a crucial juncture in the history of the proprietary colony of North Carolina. In 1663, eight noblemen and knights who had played important roles in restoring the monarchy had been rewarded by Charles II with a generous grant of land in North America that would be named Carolina after him. The practice of privatizing the British realm’s expansion had dated from the days of Elizabeth I, but no other monarch would match Charles II’s liberality in granting the vast domains of Carolina, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The monumental dimensions of Carolina alone were breathtaking: a prodigious swath of North America stretching from Virginia to Spanish Florida and from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

From Albemarle County in northern Carolina, settlement had spread south of Albemarle Sound to Bath County, which bordered the Tuscarora Nation. This new county enjoyed better sea communications through the deeper Ocracoke Inlet, which gave access to larger vessels, although small sloops and schooners continued to carry most of the colony’s trade. Hampered by poorer connections to the North Atlantic trade network than its neighbors’, northern Carolina had grown slowly at first, attracting small landholders who at the outset relied chiefly on indentured servants. Soon they began importing African slaves. By 1720, North Carolina supported 18,000 Europeans, 3000 Africans, and an undetermined number of American Indians. In smaller South Carolina’s plantation society, enslaved Africans significantly outnumbered the Europeans.

Charles Town was a substantial city of 2000 whites and half as many blacks, while the four towns of North Carolina—Bath, Beaufort, Edenton, and New Bern—altogether boasted perhaps 400 people. The earliest, Bath, had been incorporated in 1706 and become the county seat. This village of perhaps a dozen houses near the Pamlico River served as the market and political center for the southern frontier, from Albemarle Sound to the Neuse River. When merchant vessels anchored there, dugouts and periaugers piled with furs put out to meet them, and the sandy lanes bustled with seamen, Indians, and planters from outlying farms. Settled in 1713, the “poor little village” of Beaufort had direct access to the ocean and the teeming marine fisheries of Core Sound nearby. Here sailors could buy apples and cider from bumboats, the mariners’ convenience market.

By the early 18th century, the colony was prospering, only to face the great ordeals of the Cary Rebellion (1708–11) and the Tuscarora War (1711–15). The rebellion was the culmination of political tension stemming from upstart Bath County’s challenge to Albemarle’s hegemony—a struggle inflamed by politicians loyal to the newly established Anglican Church, who ousted Quakers from the General Assembly by imposing a test oath. The colony was torn by religious and political dissension from 1705 until 1711. when the powerfully connected new governor, Edward Hyde, finally drove his disaffected predecessor, Thomas Cary, from the colony. But the political machinations and power struggles had left the colony weakened.

The American Indians of North Carolina, who had long endured encroachment on their lands, dishonest trading, and the enslavement of their young people, were well aware of the divisions among the whites. Unable to bear any more, the charismatic Tuscarora chief King Hancock forged a powerful confederacy that fell without warning upon the settlement south of the Pamlico River on September 22, 1711. Hundreds of settlers were killed, wounded, or enslaved. Bath was flooded with refugees, among them approximately 300 widows and orphans. Governor Hyde secured funding and militia drafts from the assembly, and the colony was finally saved by two expeditions from South Carolina.

When the pirates descended in the late spring of 1718, they found settlements isolated amid widespread devastation. Bath County was just starting to rebuild, and the colony’s treasury was depleted. The Tuscarora had been crushed, but the various truces and the treaty of 1715 had not ended the violence. Three years later, renegade bands were still raiding isolated farmsteads and alarming the residents of Bath.

It was evident that the pirates were experienced fighting men who might prove invaluable. Some no doubt drifted off to Virginia, Pennsylvania, or New York, but most probably remained, finding at least a lukewarm welcome among the many widows and anxious townspeople. The abandoned farmsteads and coastal waters teeming with fish and mollusks also must have appeared attractive. Once the pirates accepted King George’s Act of Grace they could settle down, marry, and live out their days in the anonymity of the Carolina backcountry. North Carolina, and particularly Bath County, could not afford the luxury of spurning these casual, free-spending outlaws who pumped some life into the moribund economy and might well spring to arms if Tuscaroran terror reawakened in the forests and swamps.

For unrepentant predators such as Bonnet and Blackbeard, North Carolina offered a useful, temporary foothold between the two rich southern ports of Charles Town and Norfolk. To those who returned to their old calling, the sparsely populated Outer Banks and many shallow inlets offered convenient hideaways. Bonnet and Blackbeard took the king’s pardon from Governor Charles Eden at Bath and then sailed away on separate courses. Bonnet ravaged the Virginia and Delaware coasts and returned to Cape Fear, where he was captured after a savage action by a South Carolina flotilla under Col. William Rhett. Before the year was out, he and most of his crew had been tried and executed.

By contrast, Blackbeard, known to North Carolinians as Edward Thatch, was in no hurry to resume “pyrating.” Hard-pressed merchants and innkeepers welcomed his cash and abundant trade goods. Ostensibly settling into the colony’s domestic life, he married the daughter of a local planter, but it was said that he took “liberties” with his neighbors’ wives and daughters when socializing with their families. Over the next four months the restless Thatch mostly traded but occasionally pilfered, moving back and forth from Bath to Ocracoke and out to sea in his eight-gun sloop. Theoretically retired from piracy, he still brought in a French “sugar ship” that he claimed had been abandoned at sea; the colony’s vice admiralty court declared it a derelict and his salvage lawful.

Thatch’s activities created enough apprehension “among some of the best of the Planters,” noted a contemporary, that they appealed to Governor Eden. More concerned about Indian raids, he ignored their pleas. Those disturbed by Thatch’s apparently cozy relationship with the seat of power secretly approached Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia, a declared enemy of freebooting, who readily agreed “to extirpate this nest of pyrates” and organized a two-pronged invasion by land and sea. Aided by local guides, Virginia marines occupied Bath on November 23, confiscating a large amount of sugar and some cotton from Governor Eden and Secretary Tobias Knight. The day before, Lieutenant Robert Maynard’s two sloops had fallen upon Blackbeard in a brief but bloody action near Ocracoke Inlet. Maynard triumphantly returned to Virginia laden with cocoa, indigo, and cotton from the pirate camp—as well as Blackbeard’s severed head, which swung from the bowsprit. Those pirates who survived were tried in Williamsburg the next March. All but one were hanged.

For almost three centuries afterward, Blackbeard’s ship lay beneath a layer of sand on the outer bar of Beaufort Inlet, except on occasion when the channel shifted course. By the latter half of the 20th century, a nexus of hurricanes and storms had cleared enough sand to expose Queen Anne’s Revenge. Beaufort Inlet had been known as the resting place of Blackbeard’s flagship from the day of its grounding by way of contemporary letters, reports, and even a story in the only colonial newspaper of the day, the Boston News-Letter. Folktales about Blackbeard and his company grew with the endless retelling, until they had gained a worldwide currency as icons of “the Golden Age of Piracy.”

The modern quest to recover the Queen Anne’s Revenge began with comprehensive research on Blackbeard by the nautical archaeologist David Moore, whose report on the 1718 wrecks attracted the attention of Phil Masters, who had founded Intersal Inc. in 1988 to research historic shipwrecks. One of Intersal’s projects involved searching Beaufort Inlet for the Spanish treasure ship El Salvador, lost in 1750. Capping an eight-year-long hunt in 1996, Masters enlisted the experienced shipwreck diver Mike Daniel to help locate the wreck. In November of that year, excited divers surfaced after examining the source of a strong magnetometer reading. They described a seafloor littered with cannon and anchors. The artifacts recovered that day, including a 1705 Spanish bell, were clearly from an earlier 18th-century wreck, more than likely one of Thatch’s vessels.

The next day, the state sent its chief underwater archaeologist Richard Lawrence and conservator Leslie Bright to examine what could be the most significant colonial shipwreck ever discovered in its jurisdiction. They confirmed the initial assessment, declared the wreck a protected archaeological site, assigned it the number 31CR314, and soon nominated it to the National Register of Historic Places. A rare landmark agreement between Masters’s Intersal, Daniels’s Maritime Research Institute, and the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources turned the Queen Anne’s Revenge and its artifacts over to the state for investigation and recovery. (To date, Intersal’s search for the Adventure has failed to discover that sloop.)

The Queen Anne’s Revenge Shipwreck Project, overseen by the Office of State Archaeology and its Underwater Archaeology Branch, has been engaged over the past 14 years in intense multidisciplinary historical and archaeological research and scientific analysis, drawing on more than a dozen universities, agencies, and institutions to produce a comprehensive portrait of the foundered vessel. The record of 31CR314 so far reveals a three-masted vessel approximately 90 feet in length and weighing 200 to 300 tons. To date, 25 cannon have been found, the heaviest being six-pounders. The latest dated artifact is a Swedish cannon of 1713, which established the wreck’s current terminus post quem, the date on or after which the ship went down. Other dramatic diagnostic recoveries have included a guinea coin weight bearing Queen Anne’s bust and a fragment of a wineglass stem commemorating the coronation of George I in 1714. Collectively, the datable artifacts stretch from 1690 through the first decade and a half of the 18th century, with a mean date of 1706. All the recovered artifacts predate 1718, the date of the wreck. This diverse assemblage reflects voyages along all the primary North Atlantic trade routes.

Coordinated by Mark Wilde-Ramsing, now head of the North Carolina Underwater Archaeology Branch, teams have gathered nearly every year since 1997 for seasons of scientific analysis, surveying, mapping, testing, photography, excavation, and the recovery of artifacts. In addition to the archaeological and conservation work, scholars from other research institutions and universities have studied the site’s formation, geology, marine biology, currents, and weather patterns.

On an ideally clear dawn, with only moderate swells and a few feet of aquatic visibility, divers laden with scuba gear and equipment convene at the Fort Macon Coast Guard Station for the brief voyage through the always choppy inlet. Once their boat is secured to a mooring buoy, the divers plunge into the emerald haze, following the cable to the sandy seafloor. A yellow line guides them through the murk until a four-foot-high mass of concreted anchors, cannon, ballast stones, cannonballs, and hull planks suddenly appears, encrusted with varicolored coral, spiny sea urchins, barnacles, and marine plants. A cloud of silvery pinfish floats near several protruding cannon. Curious grouper, sheepshead, sea bass, and puffers check out the divers, while a resident octopus cautiously peers out from under his cannon sanctuary. A diver’s fin disturbs a ray, which explodes from the sand in search of a quieter resting place.

The divers fan out across the site to their assigned tasks. A team carrying metal stakes, coils of line, and heavy hammers swims south to expand the grid of 10-foot squares on the seafloor. Others begin filling sandbags to form a bulwark for the fragile exposed hull. Those mapping and drawing take their tapes and slates north to the massive anchor protruding some seven feet above the sand. The team uses a level and a stadia rod to take elevations on the mound. Photographers, including a videographer, swim around, documenting divers at work and recording artifacts and features in situ.

In one excavation unit outlined by a 10-foot-square metal frame, a skilled dredging crew is delicately removing the overburden of sand from a cannon and several unbroken dark green wine bottles. Their pace slows as they uncover tiny European glass and African ceramic beads, or spot microscopic grains of gold glittering in the sand nearby. On the surface the dredge spoil is run through sluice boxes and successive screens to trap the tiniest objects. The shallow depth of just more than 20 feet enables the divers to work throughout the day in the physically demanding underwater environment, where the main obstacle is a current that can reduce visibility from a few feet to a disorienting zero.

The early years of the dive were spent on testing and surveying, with limited excavation. In 1999 a complete magnetic gradiometer survey determined the limits of the artifact pattern and located metal concretions that could indicate large objects such as cannon. Beginning with the stern in the fall of 2006, total excavation has now extended over half the site, up to the mound.

To date about 300,000 artifacts have been recovered and transferred to the care of chief conservator Sarah Watkins-Kenney and the staff of the QAR Archaeological Conservation Lab at the East Carolina University campus in Greenville. Among the armaments are 25 cannon (most still loaded), ranging from six-pounders to a small signal gun, of which a dozen have been recovered. Besides the outstanding array of early 18th-century artillery, the search has turned up tens of thousands of musket balls and swan shot, cannonballs, parts of muskets and pistols, a decorative sword hilt, and iron hand grenades.

Domestic and personal items include tableware and marked English pewter plates and chargers, fishhooks, lead fishing weights, sewing needles, thimbles, and clay smoking pipes. Among the numerous shards of glass and ceramics are whole onion-shaped wine bottles, made around 1710. Medical items include mortars and pestles, apothecaries’ measuring cups, and a pewter urethral syringe with vestiges of mercury, used to treat venereal disease. A large collection of brass navigation and surveying instruments served the ship’s commanders. Structural elements—deadeyes from the rigging, a bilge-pump screen, hull planks and ribs, a large section of the sternpost, and a flanged lead-pipe “seat of ease” (privy)—have been recovered from the wreck itself.

Over these 14 years of research by American and European scholars, evidence revealed from the artifacts, combined with painstaking study of the historical records, has left no doubt that the wreck is indeed Queen Anne’s Revenge. Four large deep-sea anchors, all still on site, support this conclusion. The anchors, rigging, and length of the wreck indicate a three-masted vessel of a weight consistent with the ship Blackbeard commanded. The artifact pattern is what would be expected of a ship sailing the North Atlantic. The provenance of the objects—predominantly French, with English a close second, and small amounts from the Dutch, Spanish, and Italian cultures—conforms with the known history of a French frigate captured by English-led pirates of various nationalities. Its African trade is substantiated by Italian glass beads, African ceramic beads, fragments of shackles, copper, and the minuscule quantity of gold dust. Their overall assemblage matches the collection recovered from the Whydah Galley, a pirate vessel that broke up in a storm off Cape Cod in 1717.

The shipping records of Charles Town reveal that, in the proprietary era, ships the size of Queen Anne’s Revenge seldom came to such deepwater ports. The fishing village of Beaufort rarely saw small sloops, much less frigate-sized vessels. Queen Anne’s Revenge, the only craft this large known to have attempted to enter the harbor, ran aground. While the wreck in Beaufort Inlet was as heavily armed as a sixth-rate naval frigate, the eclectic mix of its artifacts and its complement of guns eliminates the possibility of its being a king’s ship. In the more or less peaceful year of 1718, merchant vessels would have carried only minimal armaments, and no English privateers had been commissioned at that time. The only possibility is the pirate vessel identified by contemporaneous reports: Queen Anne’s Revenge.

Once conserved, many of the artifacts will go on display this summer in a major new exhibit at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort. (For more information, visit www.ncmaritimemuseums.com .) Other museums in the state system will mount smaller exhibits.

Arguably the most important ship of the Golden Age of Piracy, Queen Anne’s Revenge opens a portal through which we can travel into the world of Blackbeard and fellow brigands as they blazed into the storied pages of history.