No one knew that oil could come from the ground until a bankrupt group of speculators hit pay dirt in northwestern Pennsylvania.

-

Winter 2010

Volume59Issue4

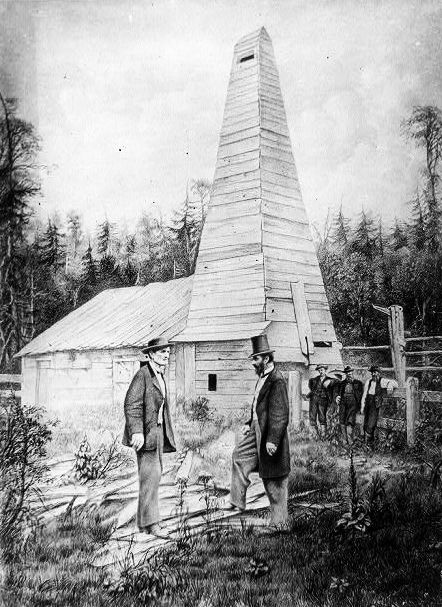

By August 1859, “Colonel” E. L. Drake and his small crew were disheartened. Few if any of the locals believed that oil—liquid called rock oil—could come out of the ground. In fact, they thought Drake was crazy. A small group of Connecticut investors had set Drake up in the small lumber town of Titusville in northwestern Pennsylvania to try this “lunatic” scheme. The work was slow, difficult, and continually dogged by disappointment and the specter of failure. After a year, the venture had run out of money, and New Haven banker James Townsend had been paying expenses out of his pocket.

At the end of his resources, Townsend reluctantly sent Drake a money order as a final remittance and instructed him to pay his bills, close up the operation, and return to New Haven. Fortunately, mail delivery to the backwoods of northwest Pennsylvania was slow, and Drake had not yet received the letter when, on Sunday, August 28, William “Uncle Billy” Smith, Drake’s driller, coming out to peer into the well, saw a dark fluid floating on top of the water.

On Monday, when Drake arrived, he found Uncle Billy and his boys standing guard over tubs, washbasins, and barrels that were filled with oil. Drake attached a hand pump and began to do exactly what the scoffers had denied was possible—pump up the liquid. That same day he received Townsend’s order to close up shop.

This event launched the American oil industry, a business that would transform the world. Had the elements not come together, and had the protagonists not possessed more willpower than reason, the birth of the industry might have been postponed another 10, 20, or 30 years.

Up until that time, Americans had lit their homes with lamps fueled primarily by whale oil. The world was running short of this commodity, and prices had reached the astronomical level of $2.50 a gallon. Finding a substitute would make a man rich.

An entrepreneur named George Bissell virtually stumbled upon the idea of drilling for “rock oil” and using it as a domestic lighting fluid. A graduate of Dartmouth College, Bissell had pursued a disparate range of jobs, from superintendent of schools in New Orleans to journalism. On his way back to the Northeast he had passed through rural, isolated northwest Pennsylvania—the back of beyond—and had come across something of the tiny rock oil industry. People gathered small volumes either by skimming it off creeks in Titusville’s “Oil Valley,” or wringing it out of rags soaked in seeps, and sold it for patent medicine. Visiting back at Dartmouth, Bissell saw a sample sent to a professor there, who said it might make a good lighting fluid. Bissell had one other flash of inspiration, supposedly from seeing the label of a patent medicine bottle in a pharmacy window, which showed a rig drilling for water. Could one drill for rock oil?

He connected with James Townsend, and they set about raising money. Townsend’s talk about drilling for oil in western Pennsylvania did not exactly garner a positive response. The banker recalled people saying, “Oh Townsend, oil coming out of the ground, pumping oil out of the earth as you pump water? Nonsense! You’re crazy.”

Bissell and Townsend enlisted the aid of a Yale chemistry professor named Benjamin Silliman Jr., who wrote a report claiming that their company had “in their possession a raw material from which . . . they may manufacture very valuable products.” With that endorsement, Bissell and Townsend were able to raise the money they needed.

But who would carry out their mission? Townsend lived in the same New Haven hotel as Edwin Drake, a retired railroad conductor and jack-of-all-trades. His most obvious qualifications were that he was available, he appeared to be tenacious in character, and, as a retired conductor, he could travel for free by rail. Dispatching Drake to Pennsylvania, the New Haven investors gave him what turned out to be a valuable send-off. Concerned about the frontier conditions and the need to impress the “backwoodsmen,” Townsend sent ahead several letters addressed to “Colonel” E. L. Drake. Thus was “Colonel” Drake commissioned out of thin air, though a colonel he certainly was not.

Drake’s tenaciousness paid off. After the discovery of oil, farmers along Oil Creek rushed into Titusville shouting, “The Yankee has struck oil.” The news spread like wildfire and started a mad rush to acquire sites and start drilling. The population of tiny Titusville multiplied overnight, and land prices shot up.

Other wells were drilled in the neighborhood, and more rock oil became available. Supply far outran demand, and the price plummeted. With the advent of drilling, there was no shortage of rock oil. The only shortage now was of whiskey barrels, into which the oil was poured. Soon the barrels cost almost twice as much as the oil they carried. (The wooden barrels may be long gone today, but not the measurement; this is why oil is still reckoned in “barrels” today.) Pennsylvania became the source from which oil promoters and drillers spread out across the country, to Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, California, and onward around the world.

But not until the beginning of the 20th century, just as electricity began to displace kerosene for lighting, did the new invention of the automobile create the modern market for transportation fuels. Petroleum went on to become a huge industry, at the crossroads of the global economy and global politics. Today oil supplies 40 percent of the world’s total energy and, as a transportation fuel, truly makes the world go round. But for its first 40 years, the oil industry primarily served lamps. John D. Rockefeller of the Standard Oil Trust became the richest man in the United States as an illumination merchant.

“Colonel” Drake did not do so well. He became an oil trader but lost all his money and finally had to appeal to the state of Pennsylvania for a modest pension. He made a good case. “If I had not done it,” he said of his oil well, “it would not have been done to this day.”