In 1917, fed up with the inaction of conservative suffragists, Alice Paul decided on the unorthodox strategy of pressuring the president directly.

-

Winter 2010

Volume59Issue4

By New Year’s Day 1917, Alice Paul, leader and founder of the National Woman’s Party, had made up her mind. Ever since coming home from studying abroad in 1910, the University of Pennsylvania PhD in political science had observed the ineffective American women’s suffrage movement with increasing impatience. She believed that for women to gain the vote—no matter how radical such a step might seem, no matter the reaction of conservative suffrage organizations—her dedicated followers in the Woman’s Party must picket the White House.

It was indeed a radical plan: no group of protesters had ever so defiantly challenged an American president. But Paul believed that such a confrontation was necessary to force Woodrow Wilson to endorse a change in the Constitution. He had assiduously avoided the suffragists’ issue and gone on record that women must “supplement a man’s life” in the home. Paul knew that only the president’s support could push the Susan B. Anthony amendment out of the congressional committees where it had languished since 1876 and might stay forever.

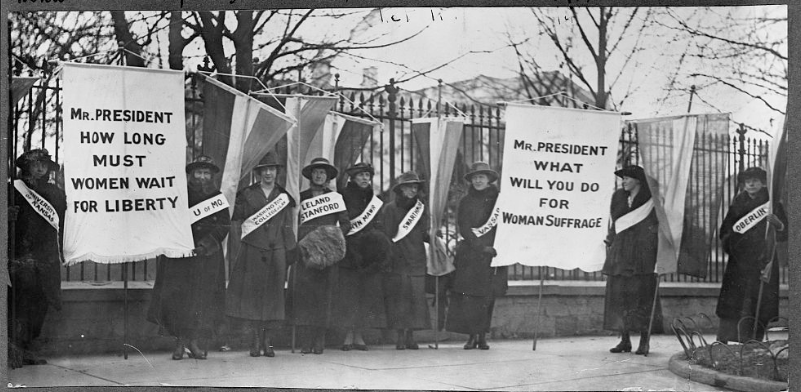

On January 11, 1917, the first militants took up their positions around the White House, where they stayed from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. five days a week, ignoring rain, snow, and sleet. Their placards, mounted on three-foot wooden boards, were clear enough: “Mr. Wilson: You promise democracy for the World and Half the Population of the United States cannot vote. America is not a democracy.” In the spring the president graciously nodded and tipped his hat as he was driven through the north gates for his afternoon round of golf. As the picketing continued, his affability grew strained.

Six months later, this embarrassing conflict escalated when Wilson authorized the suffragists’ arrest for obstructing traffic. At least 60 middle-class women chose jail instead of paying a fine. In October police arrested Paul for the third time. She received a seven-month sentence at Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse. Denied legal counsel, she demanded political prisoner status, and was thrown into a “punishment cell,” barely escaping institutionalization at St. Elizabeths Hospital, where she could have been detained indefinitely as a mental patient. When she began a hunger strike, Paul was force-fed through a rubber tube pushed up a nostril. Soon word of the brutality leaked to the press. Under mounting public pressure, Wilson pardoned the jailed suffragists.

By early 1918, he had further capitulated, making a special address to the Senate that called for support of the suffrage amendment as a reward for women’s war service, not as a natural right of all Americans. In due course the Senate and House passed the amendment by the requisite two-thirds, and, by June 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had been ratified by three-quarters of the states.

This decisive moment in American history and what it owed to Alice Paul’s militancy are often overlooked because the vote seems so obviously a right of all Americans. Nor have the difficulties of this struggle for civil rights entered the larger story of the national heritage. But, in the early 20th century, the Nineteenth Amendment was far from a sure thing. In 1900, despite the crusade that had begun in 1848 at Seneca Falls, New York, and continued after the Civil War through the efforts of dedicated suffragists such as Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucy Stone, only four states had enfranchised women. The unwieldy process of state-by-state enfranchisement routinely met defeat in referenda; national and state legislators lost no voting constituency when they simply avoided the issue. Men resisted giving women the vote because it would significantly change women’s civic status in a way that could clearly undercut so many traditional arrangements of family life.

For half the population, voting marked a crucial step toward equality, offering the essential political utility by which they could achieve other improvements in their standing, such as bringing down the barriers that prevented them from negotiating their wages, attending state universities, and serving as officeholders and on juries—though the latter remained a contested civic obligation into the 1940s. If able to vote, women could act as the moral guardians of the nation, influencing domestic politics and turning attention to issues involving children. Without it one-half the population had no civic standing.

That morning in January 1917, when Alice Paul and the members of the National Woman’s Party began picketing the White House, they took a critical step toward equality for women. Otherwise, it’s difficult to know how long American women would have remained politely but firmly marginalized. But, as Paul recognized, earning the right to vote was only a beginning. Soon afterward, she proposed the next step by writing the still-to-be-enacted Equal Rights Amendment.