In the hundred years since his death, features of Woodrow Wilson’s philosophy have become central to international politics and American foreign policy.

-

Fall 2024

Volume69Issue4

Editor's Note: Michael Mandelbaum is professor emeritus at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and the author most recently of The Titans of the Twentieth Century: How They Made History and the History They Made, a study of Wilson, Lenin, Hitler, Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gandhi, Ben-Gurion, and Mao, just published by Oxford University Press, from which this essay was adapted.

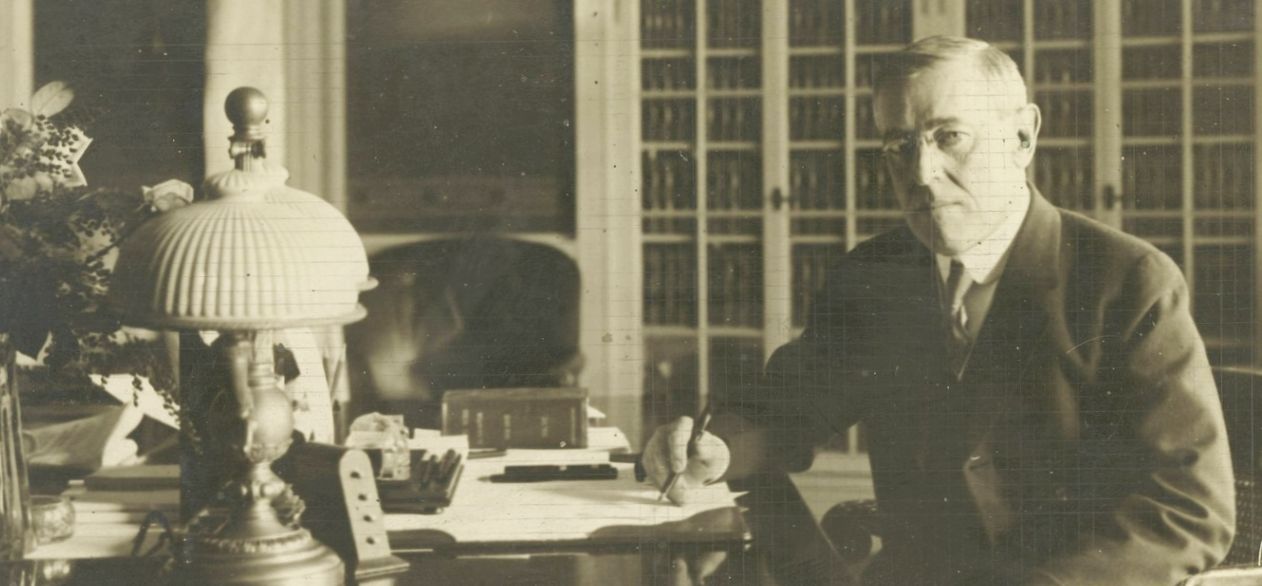

A century after he died in 1924, Woodrow Wilson remains a major presence in American foreign policy. One distinguished historian of American foreign relations, Robert W. Tucker, wrote that “in the history of America’s encounter with the world, Woodrow Wilson is the central figure.” According to another, George Herring, “Wilson towers above the landscape of modern American foreign policy like no other individual – the dominant personality, the seminal figure.” What accounts for this posthumous prominence?

It does not stem from any resounding successes which American foreign policy achieved during his presidency. While he presided over the country’s participation in World War I, compared with other wartime presidents, he played a relatively minor role in that conflict. Unlike Franklin D. Roosevelt and World War II, Wilson himself did little to propel the United States into the war: the country was swept into it by public outrage at German submarine warfare. Also, unlike his successor, Wilson made no major wartime strategic decisions comparable to Roosevelt’s emphasis on the European, rather than the Pacific theater, or his designation of the timing of the Allied invasion of France in June, 1944.

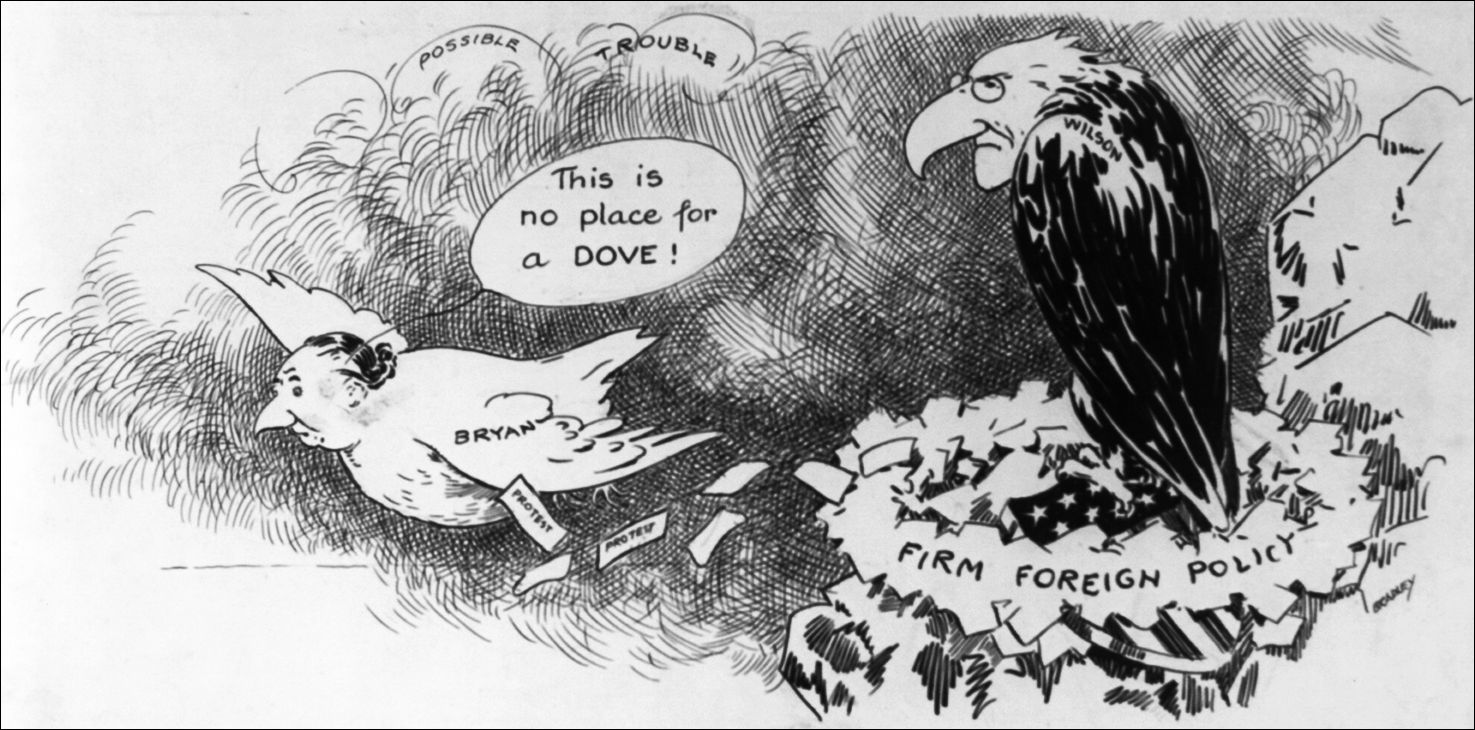

In fact, American entry into the war may be seen as a significant, albeit inadvertent, failure of Wilson’s foreign policy. He wanted his country to remain strictly neutral, with the definition of neutrality including trade with both sides in the conflict. Britain used its naval superiority to try to starve Germany and Austria-Hungary into submission. Its blockade of enemy ports made American neutrality effectively pro-British.

In response, the Germans conducted submarine warfare in the Atlantic, which eventually pushed the United States into the war on Britain’s side.

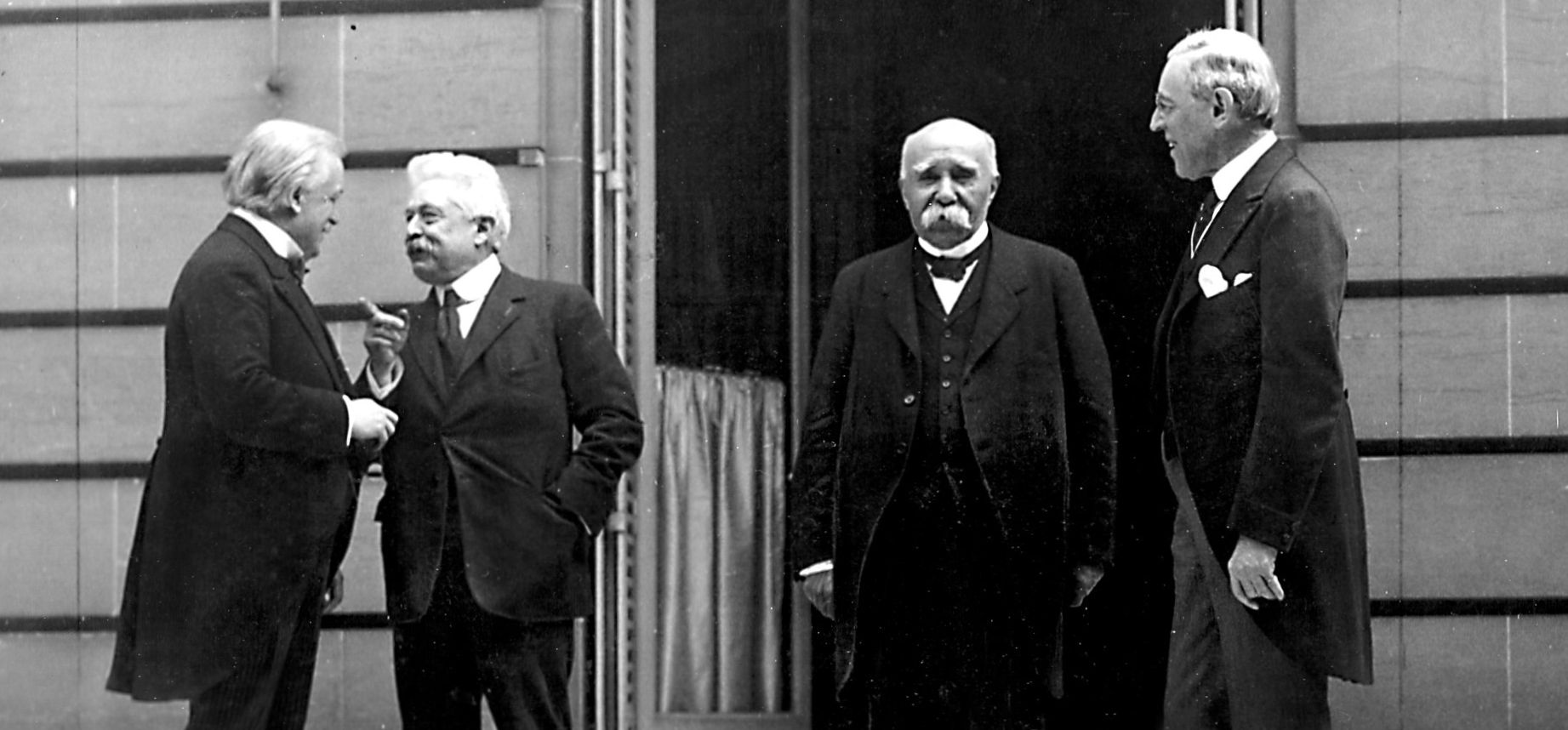

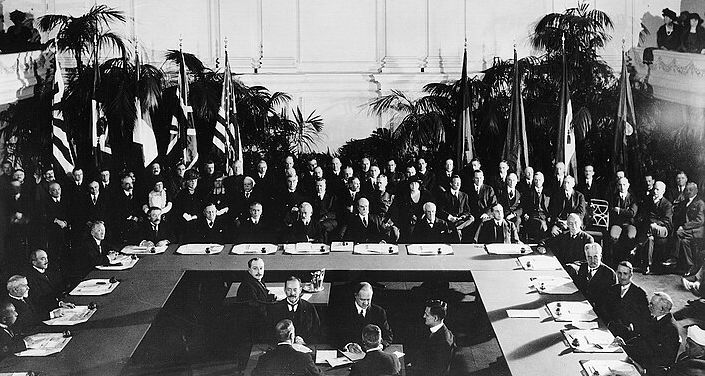

Wilson did play a major role in the Peace Conference at Paris that followed the war, but he did not achieve his principal post-war aim: getting his country to join the international organization intended to keep the peace -- the League of Nations -- that he had done a great deal to establish. Nor did the post-war political settlement that emerged from Paris, of which he was a principal architect, achieve its preeminent goal: an enduring peace. Two decades later, Europe was again at war.

Woodrow Wilson’s ongoing importance stems not from what he did, but from what he wanted, but largely failed, to do. His impact on American foreign policy and international politics more generally comes, not from his policies while in office, but from his ideas about how to organize the world, which have lived on after him. He has proven to be an unsuccessful statesman, but an enduringly relevant prophet.

Wilson’s ideas, taken together, constitute a distinctive approach to international politics and foreign policy that has come to be known as “Wilsonianism.” It contrasts with, and offers an alternative to, the historically typical approach often called “realism” – in French raison d’état, in German Realpolitik, and in English, “power politics.” Realism emphasizes the centrality of power and armed conflict in relations between and among sovereign states. In the realists’ understanding, the system of such states resembles a jungle, with insecurity a common condition of all its members. For that reason, all states can, do, and must anticipate, prepare for, and sometimes wage war.

Wilson presented his ideas as a means of transforming the international order, abolishing war, and turning the world from a jungle into something more like the internal workings of peaceful, democratic countries – such as the United States.

To be sure, the ideas he put forward did not, for the most part, originate with him personally. The impulse to reconstruct the world to make it more peaceful had formed part of the American outlook on international affairs since the eighteenth century; and other countries, notably Great Britain, had preached, and even practiced, some of the principles that he propounded.

Still, the ideas deserve to be called Wilsonian because Woodrow Wilson gathered them together and placed them on the world’s agenda in the wake of World War I, where they have remained ever since. He was able to do so because of that war, which had caused so much loss of life and destruction of property that it gave rise to a powerful worldwide demand for measures to prevent another one.

The prominence of Wilson’s ideas had another cause: the office he held. The words of the president of the United States commanded global attention because of the power of the United States. The country’s first secretary of state and third president, Thomas Jefferson, had also sought to abolish war. His efforts to do so had had virtually no impact on the wider world, however, because the newly established United States, weak and distant from the centers of global power in Europe as it was, had only a very minor presence in international affairs. A century later, Wilson, by contrast, presided over a country with the world’s largest economy, whose entry into the recent war had enabled the British and French to win it.

Wilson’s ideas have never come to dominate the foreign policy of the United States, let alone those of all other countries. American foreign policy has retained a powerful realist strain, and now more than ever when three aggressive powers – China, Russia, and Iran – threaten American interests around the world. The Wilsonian approach, however, has had, over the last hundred years, increasing influence in the international system and on the American role in it. The world has not become entirely Wilsonian, but, since his death in 1924, it has adopted an impressively large part of his vision. That is why these hundred years may be called the Wilsonian Century.

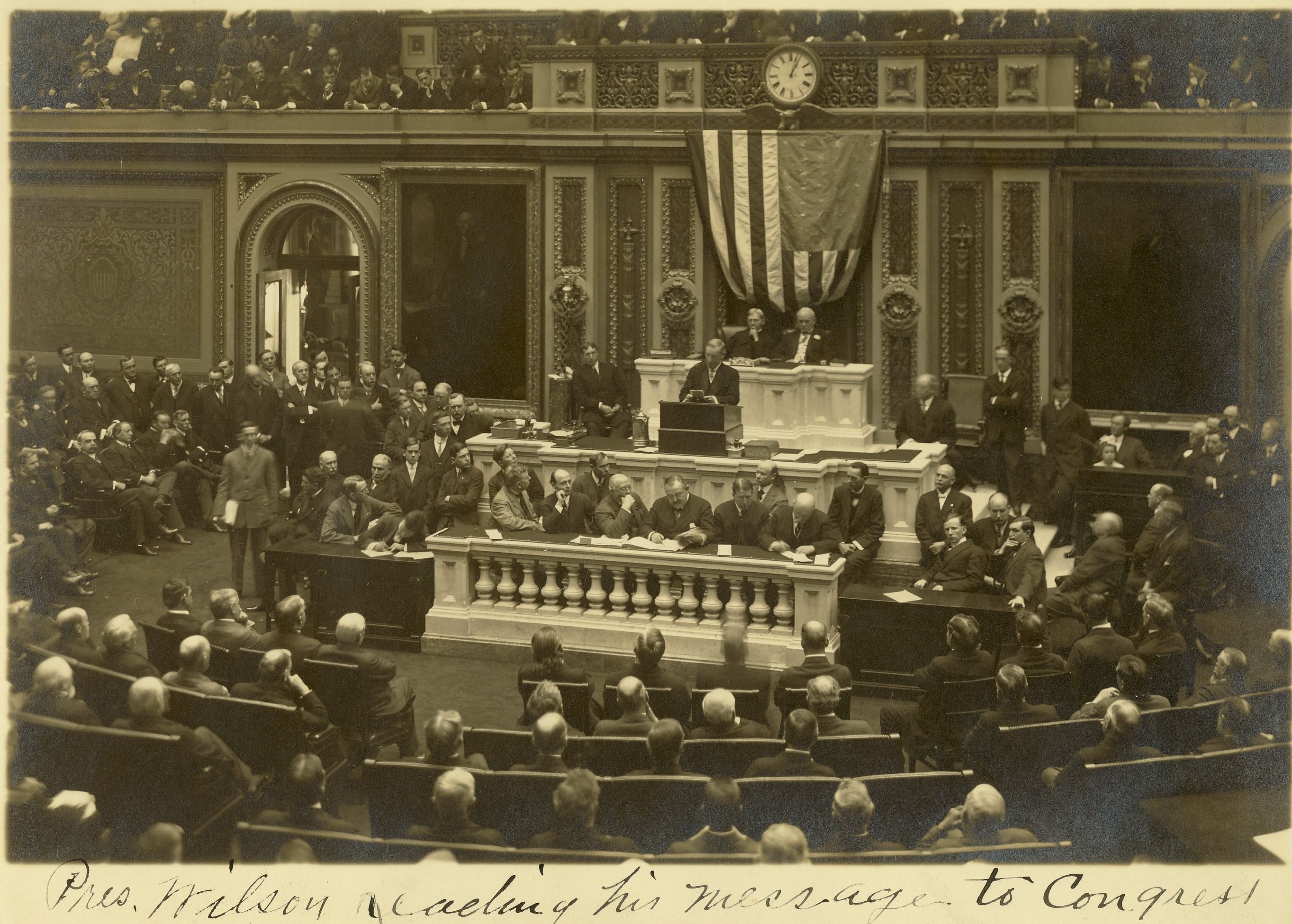

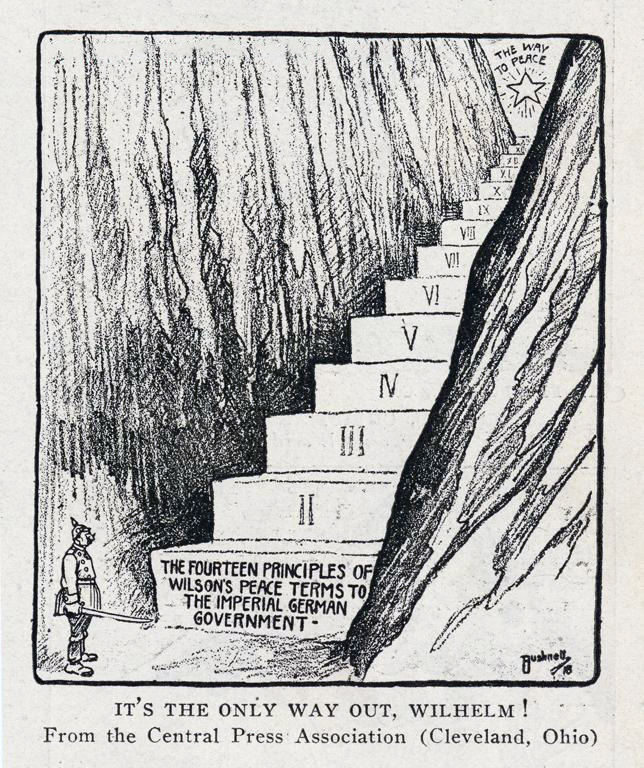

The approach to international reform that Wilson proposed had five principal features, which he set out in his January 1918 address to the American Congress listing the nation’s war aims. It became known as his “Fourteen Points” speech. Perhaps the most important of them was national self-determination – the principle that sovereign states should be composed of single national groups. Points six through thirteen of the speech called for post-war territorial adjustments based on this principle.

Wilson did not invent it. The idea that nations should form the basis of states stems from the French Revolution. The Declaration of the Rights of Man of 1789 states that “the principle of sovereignty rests essentially in the Nation . . . no body of men, no individual, can exercise authority that does not emanate expressly from it.” During the 19th century, the German and Italian people had put the idea into practice, in each case uniting several smaller political jurisdictions in a single state.

The national principle was incompatible with, and ultimately replaced, what was until World War I the predominant form of political organization on the planet – the multinational empire. This was in keeping with long-standing American sentiment. Wilson’s own country had become independent through a rebellion against an empire – that of Great Britain – and the United States had usually, although not always, opposed any form of imperial rule.

Second, Wilson wanted sovereign states to be governed democratically. He did not give the same prominence to democracy that it was to attain, especially in the foreign policy of his own country, in the course of the Wilsonian Century. Nor did he offer specific guidance on how to foster that form of government. He seems to have assumed that, once states were composed of single nations, they would become democracies more or less automatically. He certainly believed that undemocratic governments did not contribute to what was his supreme goal: peace.

Wilson singled out as crucial for a peaceful world the free flow of international commerce and the freedom of the seas that made it possible. This was the third tenet of Wilsonianism. Here, he adopted as central to his program policies that Great Britain had carried out in the 19th century. An influential current of British opinion in that century had held that international commerce not only created wealth, but also, because the participants in it had an economic interest in avoiding war with one another, made the world more peaceful.

Wilson made the reduction of armaments the fourth of his Fourteen Points, and thus a distinctive part of the approach to international relations that came to bear his name. The principle implies that weapons cause war, a debatable proposition since armed conflict ordinarily arises not from the existence of weapons but from political disputes: countries in conflict are not adversaries because they are armed; they are armed because they are adversaries. Nonetheless, the idea did not die with Woodrow Wilson: it has lived on since his death.

Herbert Hoover gave an assessment and recollections of Wilson

at the Paris peace talks in his 1958 essay for American Heritage.

Fifth and last – but, for Wilson, certainly not least – he advocated, in the last of the Fourteen Points, “a general association of nations . . . for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” Others had suggested a postwar international organization of this kind before Wilson did so, but he became its leading proponent, and from that idea came the League of Nations.

Of Wilsonianism’s five component parts, Wilson himself imputed the greatest importance to this last one. Once established, he believed, the League would develop, grow, embed itself in the fabric of international relations, and cope with any war-threatening international problems that might arise. This did not happen, but the idea of an international organization to keep the peace did not disappear.

In different forms and to different degrees, all five features of Wilsonianism have become part of international politics and American foreign policy, and some have flourished in the century since Woodrow Wilson’s death. In this sense, the world has become much more Wilsonian.

For the purpose of allocating sovereignty, the principle of national self-determination has achieved hegemonic status. In the 21st century, it is widely accepted as the only legitimate basis for statehood. The world’s great multinational empires – with the exception of the one over which the Chinese Communist Party presides, which forcibly includes millions of Tibetan Buddhists and Uighur Muslims – have all disappeared. True, applying the national principle that Wilson promoted has sometimes proven difficult. The world’s population was not and is not divided into discrete, self-contained, homogenous national units with clear boundaries between and among them. To the contrary, different peoples were and are intermixed.

For that reason, drawing borders has often become contentious and has all too often led to bloodshed. No better formula for statehood being available, however, in the 21st century, the national principle remains the approved basis for drawing the world’s international borders.

As for democracy, it, too, has become far more common than it was in Wilson’s day. It spread throughout the world in two distinct historical waves – the first after World War II and the second beginning in the 1970s and cresting in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the fall of communism in Europe. Estimates of the extent of democratization vary according to the criteria chosen for democratic government, but the expansive trend is clear: by one count, in 1900, only ten democracies existed, whereas, by 2005, fully 119 of the world’s 190 countries had some claim to that status.

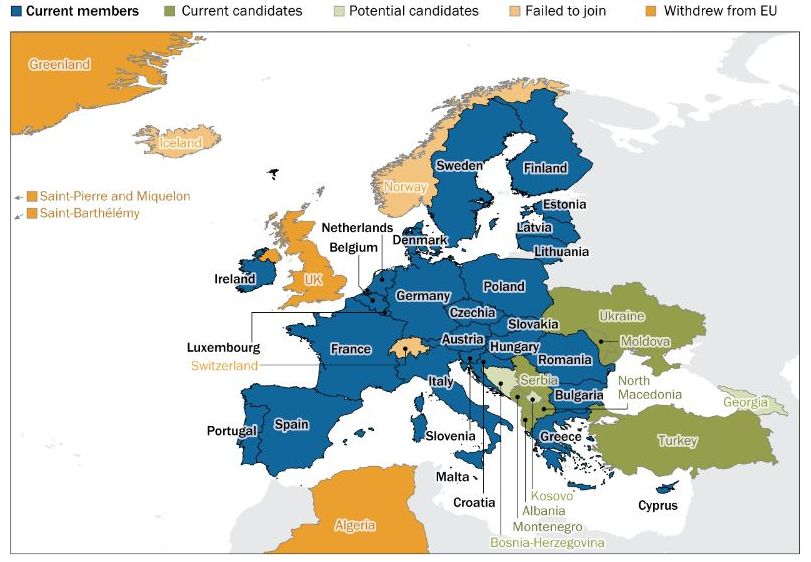

The free trade and freedom of navigation that Wilson had included in the Fourteen Points also became more widespread in the second half of the twentieth century and thereafter than had been the case in his day. The combination of the two became known as globalization. In particular, unfettered trade served as the basis for the ongoing economic and, to a limited extent, political integration of Europe, which now takes place within the framework of the European Union.

By 2024, the EU included 27 member countries. It had as its founding purpose the promotion of peace through economic ties between France and Germany, which had fought three destructive wars in 75 years. For economic and other reasons, since the beginning of economic integration, Western Europe has enjoyed uninterrupted peace. While European initiatives and decisions created the EU, because the overall goal of the component parts of Wilson’s program, including trade, was peace, the EU qualifies as a Wilsonian project.

Another of the Fourteen Points, the reduction of armaments, also came to fruition in the aftermath of Wilson’s public career. The world experienced two periods of negotiated arms limitation after World War I. Both contributed to peace – or at least to the relaxation of international tensions – because both came about in the context of a larger effort to reduce, or at least to contain, the political differences among the signatories; and those differences, rather than the weapons themselves, had the potential to lead to war.

The Washington Naval Treaty and attendant agreements of 1922 formed the basis for a general, although short-lived, political settlement among the great powers of Asia. Later in the century, in the 1970s and 1980s, the United States and the Soviet Union signed a series of nuclear arms control accords as part of an effort to moderate the dangers of the Cold War by limiting, although not ending, their global rivalry.

The world became more Wilsonian in the century after Woodrow Wilson’s death in one final way. The second half of the twentieth century became the great age of international organizations, although not in the way that Wilson had envisioned. A successor body to his League of Nations, the United Nations, did come into existence, but was not given the kind of authority to intervene in conflicts around the world that Wilson had wanted the League to have. Peace in Europe did follow World War II, but rested on a realist, not a Wilsonian base, with a balance of power between two opposing multinational coalitions. The United States led the Western coalition, which took the form of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, while the Soviet Union led the Eastern Bloc including Central and Eastern European countries.

The most numerous and effective post-Wilson international organizations had as their principal purpose the fostering and regulating of economic cooperation among sovereign states, rather than peace and security. The international cooperation that Wilson had foreseen thus did come to pass, but not in the sector of international relations in which Wilson had anticipated it.

Woodrow Wilson’s political ideas have done more than survive him: they have had something like the kind of impact for which he hoped. His overriding goal was international peace; and during the Wilsonian Century, and especially after 1945, the world has, on the whole – with conspicuous exceptions, and with the caveat that past performance does not guarantee future results – enjoyed greater peace than before. The causes of such peace as the world has experienced go beyond Wilsonianism, but surely include it. If Woodrow Wilson left an immediate legacy of failure, therefore, the long-term consequences of his public career (although hardly of that alone) appear more successful.

The efflorescence of Wilsonianism in the last three-quarters of the 20th century and the first quarter of the 21st has various causes, but one in particular stands out: the efforts of his own country to put the ideas that comprise it into practice. Over that period, for example, the United States consistently advocated national self-determination, sometimes in opposition to otherwise friendly democracies – most notably Great Britain – that wished to retain their empires. America also did more than any other country to promote democracy around the world.

The American government encouraged European integration and assumed broad responsibility for globalization. It supplied the open markets and naval support that Great Britain had provided for the globalization of the nineteenth century. The United States took the lead in negotiating the arms treaties of both the 1920 and the 1970s and 1980s and in creating and sustaining the many international organizations that were established after World War II.

It is not surprising that Wilsonian ideas resonated with Americans, since they comported with the long-standing national optimism that societies can be changed for the better, and with its founding commitment to liberty – national self-determination being the concept of individual liberty applied to nations.

While those ideas predated Wilson’s presidency, they became far more relevant to international politics when the United States grew powerful enough to mount serious efforts to put them into practice. World War I, which coincided with Wilson’s presidency, marked the moment when the country came to have the stature and the resources to undertake such efforts. For most of the hundred years that followed, the United States has been the most powerful and influential country in the world. Its ideas have therefore mattered a great deal.

For all its devotion to Wilson’s ideas, the United States has never abandoned the opposing, realist approach to foreign policy. Not only that, but when the imperatives of the two have come into conflict, the American government has usually chosen realism – as when it allied with the totalitarian Soviet Union in World War II for the purpose of defeating Nazi Germany. Indeed, the more deeply involved the United States became in international politics during the Wilsonian Century, the more important the imperatives of power politics came to seem. Yet the country never rejected Wilsonianism.

Since Wilson’s day, the two approaches have coexisted in America’s relations with the rest of the world. Franklin Roosevelt presided over American participation in the bloodiest war in human history, but also issued in 1941, along with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the Atlantic Charter, a list of war aims (before the United States had formally entered World War II) that echoed Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Every subsequent president has conducted a foreign policy that included both approaches.

Wilson’s ideas have not always seemed, to everyone, unalloyed assets for the United States. They have provoked the periodic concern, espoused in particular by the diplomats George F. Kennan and Henry A. Kissinger, that America would conduct its foreign relations as if the world that Wilson had wished to create already existed, and thus neglect the requirements of power politics, which could lead to setbacks at the hands of aggressive and emphatically non-Wilsonian countries.

In addition, one particular project very much in the Wilsonianism spirit did not end well for the United States. In the quarter-century following the end of the Cold War in 1990, for a variety of reasons, America undertook several attempts at “nation-building” – trying to install decent, competent, democratic governments in Bosnia, Somalia, Haiti, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq. These efforts all fell short of the goals that the United States set for them, in the last two cases, at considerable cost in lives and money.

Still, the American commitment to Wilson’s ideas has persisted; and these ideas, distinctively American as they are, count as a significant contribution of the United States to world history. The commitment is aspirational: Americans hope to make the world over in the image that Woodrow Wilson depicted.

That aspiration is not ignoble: the world would be safer and more prosperous if Wilson’s ideas could be realized everywhere. Nor is the aspiration entirely fanciful: the world has after all become more Wilsonian in the last one hundred years.

The Wilsonian aspiration is, finally, all but inevitable, because Woodrow Wilson’s ideas are so firmly lodged in the political culture of the United States. While Americans have not and likely cannot fully implement those ideas, neither have they discarded them, and probably never will.