The boy's vicious killing in Mississippi in 1955 helped to transform America's racial consciousness.

-

Fall 2024

Volume69Issue4

Editor’s Note: Ronald K.L. Collins is a retired law professor, noted legal scholar, and the author or co-author of 13 books. He recently published Tragedy on Trial: The Story of the Infamous Emmett Till Murder Trial based on the discovery of long-lost transcripts of the trial proceedings. His book was called “groundbreaking” by Janai Nelson, CEO of the NAACP Legal Defence Fund, and Congressman Bobby Rush hailed it as “a long-overdue and indispensable account of the 1955 trial."

September 3, 1955 marked a turning point in the history of racial justice in America. On that Saturday, a crowd gathered at the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago to attend the funeral for Emmett Till, the young Black boy who had recently been savagely murdered in Mississippi.

Till’s mother, 33-year-old Mamie Till Bradley (later Mobley), decided to have an open-casket funeral:.“Let the people see what they did to my boy,” she famously declared to the world. For several days, thousands (including the elderly and young alike) came to bear witness to this horrific display of brutality born of bigotry. As Reverend Jesse Jackson put it so well nearly a half-century later, “Mamie turned a crucifixion into a resurrection.”

Two weeks later, Jet Magazine ran a story of the lynching (“Nation Horrified by Murder”) replete with photos taken by David Jackson of the boy’s ghastly disfigured face. Those photos, which only appeared in African American publications, stirred people to act.

Collective suffering was the response, a way to let the light of grace break through the darkness. In so many meaningful ways, the funeral and the photos marked the beginning of the modern civil rights movement.

A Murder Most Foul

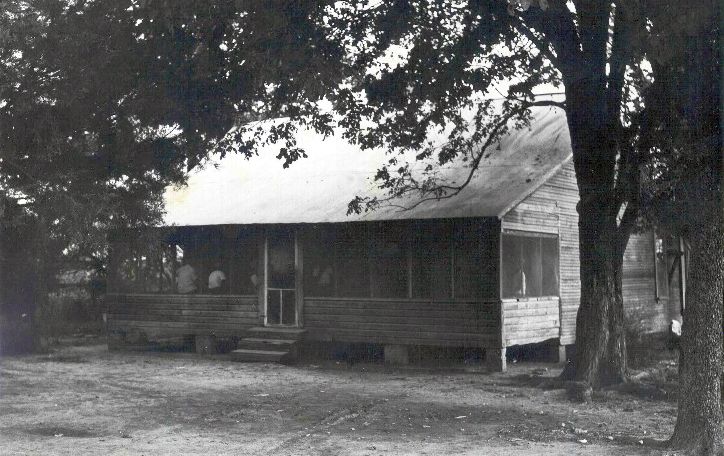

It had all begun less than a month earlier. On August 20, 1955, Emmett was 14 years old when he left his Chicago home on a Saturday to board a train to Mississippi for two weeks of fun with relatives. A town near Money was his destination; he would stay at the home of his great uncle, Mose Wright. Jovial and big-city care-free, the boy was unfamiliar with the lethally prejudiced ways of the Deep South. Before he left Chicago, Mamie had given him “the talk" regarding the dos and don’ts of survival behavior around whites in the Deep South.

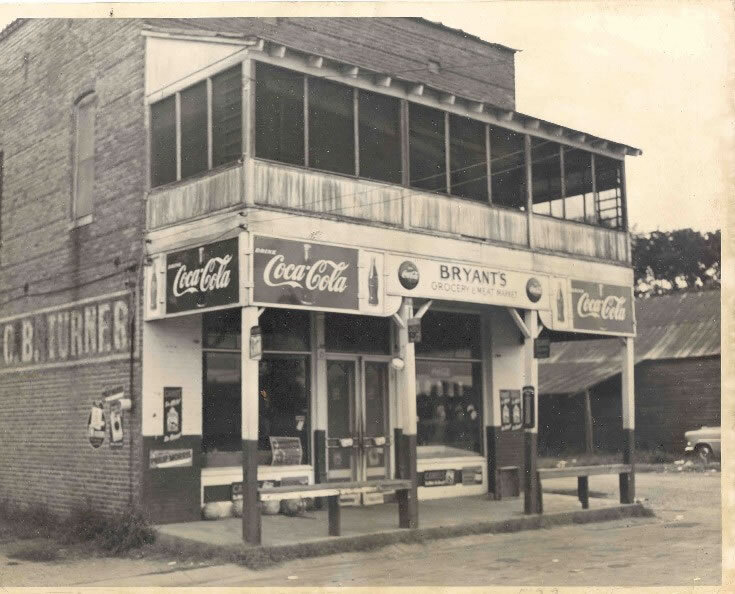

Four days after he left Chicago and arrived in Mississippi, “Bobo” (as he was known), ventured with seven cousins and a few other kids to Bryant's Grocery & Meat Market in Money. It was Wednesday, August 24. After one of his cousins bought something, Emmett entered and browsed around, while Carolyn Bryant, whose family owned the store and was behind the counter, looked on.

Since the two were alone at the time, what went on when Till made a purchase and interacted with the 21-year-old white woman is unknown. (Bryant would later deceptively embellish the story when she was called to testify at the murder trial).

Whatever transpired, too much time had elapsed for a Black boy and a white woman to be alone. One of Emmett’s cousins thus entered and quickly escorted him from the store. Shortly afterward, and for whatever reason, Carolyn Bryant ran out to get a gun from her sister-in-law’s car.

As she exited, Emmett whistled (what came to be called a “wolf whistle”). Correctly realizing the danger of the situation, the other Black kids grabbed him and left with terrified dispatch.

Predictably, things escalated, though Mose Wright was unaware of the perilous situation until Carolyn’s husband Roy Bryant and her brother-in-law J.W. Milam pounded on Wright’s door at around 2:00 a.m. four days later.

At the trial, Mose Wright (aka “the Preacher”) described what happened:

“Well, someone was at the front door, and he was saying, ‘Preacher, Preacher.’ And then I said, ‘Who is it?’ And then he said, ‘This is Mr. Bryant. I want to talk to you and that boy. . . . Well, I got up and opened the door. Mr. Milam was standing there at the door with the pistol in his right hand and he had a flashlight in his left hand. . . He asked me if I had two boys there from Chicago. I said, ‘Yes Sir.’ . . Then, Mr. Milam said, “I want that boy that done the talking down at Money.”

Shortly afterward, Emmett was stolen away by Milam, and Bryant (and likely aided by others). They took him by force; this was clearly a kidnapping crime, and one they were arrested for but never charged with.

What followed was hours of torture of the vilest kind – white men savagely beating a Black boy until his life was pounded out of him, blow by horrific blow followed by a bullet to his brain. To compound their evil, Milam and Bryant drove miles to steal a 74-pound cotton gin fan, which they fastened to Till’s neck with barbed wire. Then they were off to the Tallahatchie River, where they disposed of the body. (The gruesome event took on renewed attention in Bob Dylan’s 1962 song “The Death of Emmett Till.”)

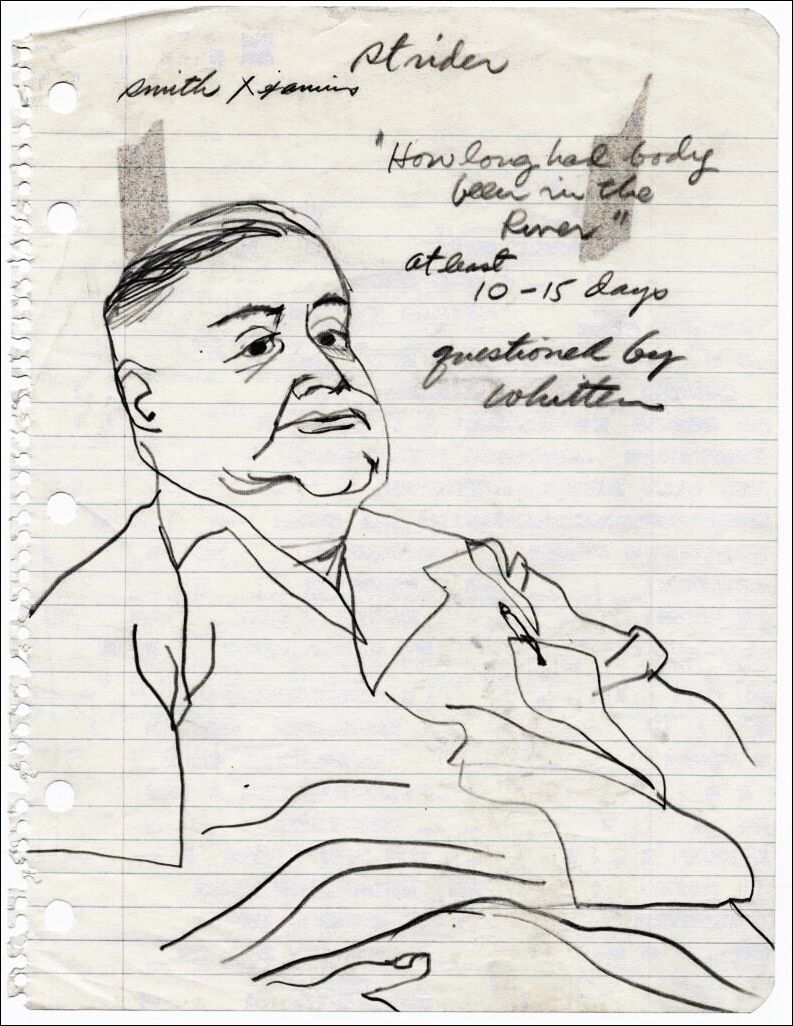

Three days and miles later, a beaten and bloated body surfaced – Emmett’s feet were spotted projecting out of the Tallahatchie. At that pinpoint in time, the sheriff, H.C. Strider (after whom a state highway is named), played a major role in working with the defense to prevent the defendants’ conviction. For example, he:

- falsely claimed jurisdiction over the location of the murder, and thus prevented the joint prosecution of Milam and Bryant for kidnapping and murder;

- ordered the immediate burial of Till and had the coffin sealed under penalty of law to prevent its opening or transportation;

- worked with the defense team from the outset and was called as a witness for them;

- After first signing a death certificate identifying the body as that of Emmett Till, he later testified under oath that it was impossible to identify the body or the victim’s age or color; and

- falsely claimed at a press conference that there were reports that Emmett was alive and well in another state and that all of this was an elaborate plan by the NAACP and others to create racial tension in Mississippi.

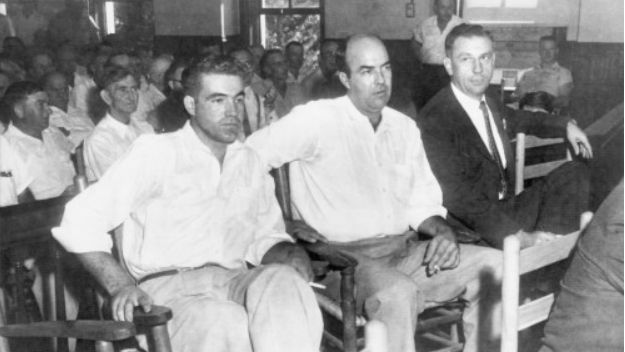

The Trial: The Defendants Smiled and Smoked Cigars

The murder trial of Milam and Bryant commenced at the Second District Tallahatchie County Courthouse in Sumner. Scores of white men lingered in front of the courthouse, with only a few black people looking on, but at a safe distance. If you take a civil rights history tour through the South, you will likely come upon the courthouse where the Till murder trial occurred between September 19th and 23rd of 1955. The courthouse is located on North Court Street in Sumner, Mississippi next to a towering Confederate statue with a chiseled tribute to “our heroes,” in memory of “the cause that never failed.”

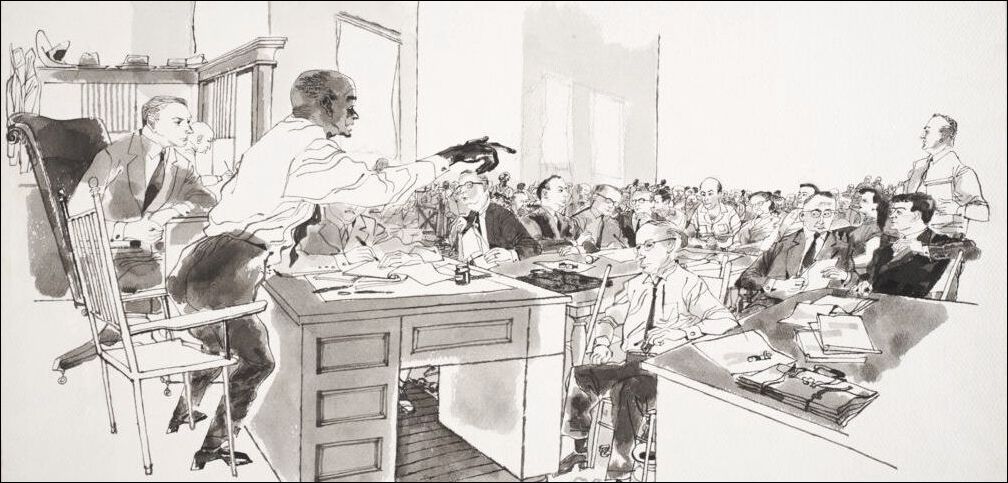

If the trial were ever to be re-enacted in the original courtroom, one could see in the mind’s eye Judge Curtis M. Swango, Jr. presiding in the front center of a wildly overcrowded courtroom. The judge banged his gavel as the two cigar-smoking defendants – J. W. Milam (six feet, two inches tall, and 235 pounds) and Roy Bryant (five feet, four inches tall, and 160 pounds) – were each joined by their young sons and accompanied by their wives.

Many Black Americans came to watch the trial, though only 50 were admitted into the sweltering, humid courtroom, with temperatures rising above 100 degrees. The open windows did little to clear the haze of cigarette smoke. Fans swirled to offer only a modicum of relief. Playing to the crowd, vendors hawked soda pops and lunch boxes during court recesses, but only to whites. Meanwhile, the young Milam and Bryant boys were rowdy as they chased one another while playing with their toy guns. Thus did the case begin.

From that same conceptual perch, one can imagine seeing Judge Swango drinking Coca-Cola as the lawyers selected jurors and the three prosecutors and five defense lawyers huddled at nearby desks. The proceeding drew worldwide attention; the national mainstream media and press correspondents included the likes of John Chancellor, Murry Kempton, and David Halberstam.

As the trial proceeded, Mississippi and Louisiana radio reporters scurried around to phone in their on-the-spot stories – “Stay tuned to hear the latest from Sumner on the trial.” Off to the side, the far side, a small card table marked the segregated spot for the Black reporters.

Mose Wright (Till’s great-uncle) was the first witness called by the prosecution. He sat in a chair to the judge’s right. It was from there, in what proved to be a historic moment captured by a camera, that Wright stood and pointed an accusatory finger at the defendant Roy Bryant.

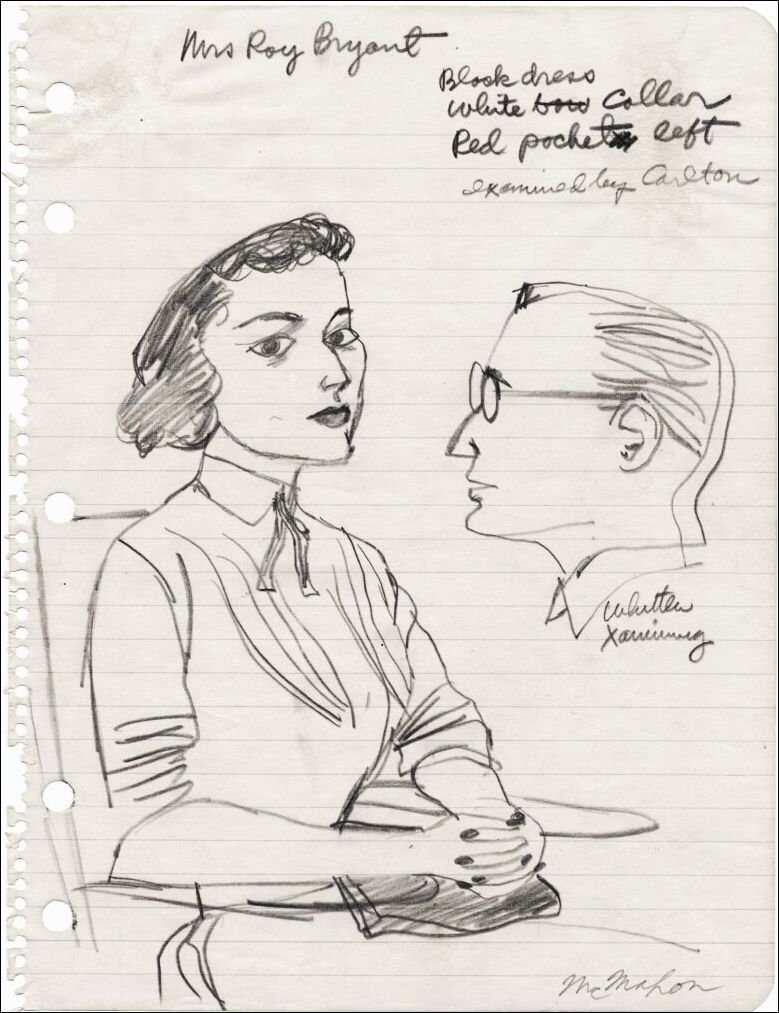

And then there are the images of Carolyn Bryant resting her head on her husband Roy’s shoulder after she testified (outside the presence of the jury) about allegedly being touched and later whistled at by Till – her testimony was offered outside the presence of the jury and ultimately excluded.

Sheriff Strider added to the fabricated tale when he rendered his perjured and all-too-defendant-friendly testimony. The testimony of the 22 witnesses (12 for the prosecution, ten for the defense) along with closing arguments lasted two-and-a-half days.

It was standard form: Whites were addressed by their surnames, while Blacks were addressed either by their first names or nicknames. In the shocking course of it all, there was also the testimony of Mamie Till-Bradley. Born in Webb, Mississippi, she had lived in a world in which race determined one’s destiny in daily life. That was apparent once she entered the courtroom where seats were segregated by race.

One of the defense lawyers, J. J. Breland, went so far as to suggest that Mamie had staged her son’s death to collect “life insurance” on him. This was the drift of his questioning when she took the stand.

Though it surely shocked many, it did not surprise the Black press that some of the key witnesses for the State, like Levi Collins (a 20-year-old Black man who worked for one of the defendants), were nowhere to be found. In all likelihood, they were seized by the authorities and taken to other jurisdictions until the end of the trial. Thus, there was a paucity of prosecutorial evidence, thanks, in no small part, to the pre-trial maneuverings of Sheriff Strider.

The tenor of the trial only compounded such evil as even the most obvious of facts tendered by the State’s twelve witnesses were cleverly and deceitfully contested by the five lawyers for the defense. The defense lawyers, aided by Sheriff Strider, even argued that the body was so badly disfigured that no one could identify it as that of Emmett Till.

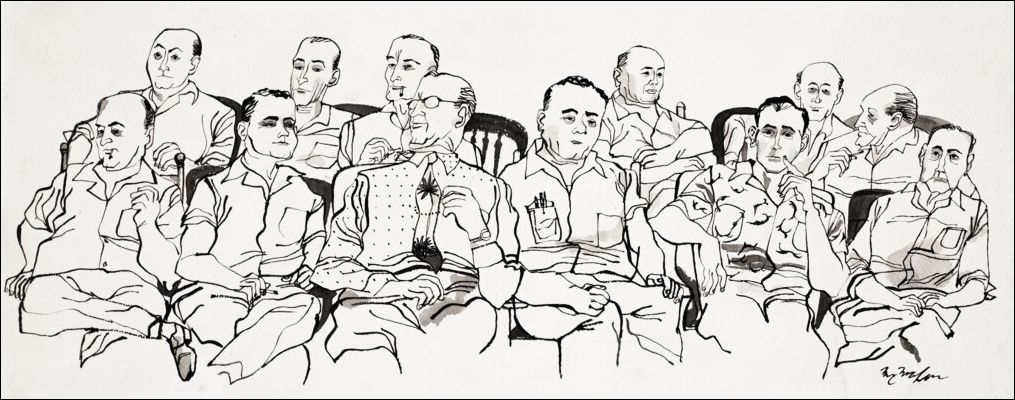

Around 3:48 p.m. on Friday, September 23, 1955, Charlie Cox, the clerk of the court, announced the verdict. The all-white male jury deliberated for 67 minutes, which included a soda break. There were reports that witnesses had heard “laughter inside the jury room during deliberations.” Once announced, the verdict won the excited approval of the white audience.

When this phase of the criminal “justice” process was done, black-and-white photographs of the smiling defendants and their wives were captured and then circulated widely. Later, a grand jury in a different jurisdiction declined to indict Milam and Bryant for kidnapping, though there was extensive evidence of that felony.

Cigars in hand and smiles on their faces, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant were smugly confident that they had gotten away with murder as they were freed from police custody. Interestingly, they were never even handcuffed while in Sheriff Strider’s charge.

Erasure. Over time, people with essentially the same motive attempted to erase much of the Emmett Till tragedy and murder trial from the memory of recorded history. For example, there was the attempted quick burial in Mississippi (to prevent national notice), the cotton gin wheel wrapped with barbed wire around Emmett’s neck (which remains lost), the missing witnesses (some of whom never spoke fully and truthfully), the long-lost trial transcript (with its curiously missing closing arguments and exhibits), the initial renovation of the courtroom (which changed its appearance considerably), the bullet-ridden mutilation or destruction of Till landmark signs (which continues to this day), and more.

In 2022, Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves signed a bill mandating how history and race are to be taught in public schools. One wonders: Will the Emmett Till story – the true story – ever be recounted in any Mississippi school textbooks?

“The Emmett Till story is an example of how history changes, depending on the narrative, how perception can become reality, and how, only through an honest appraisal of the evidence, can we piece together what truly happened,” says Lonnie G. Bunch, III Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

Injustice. The specter of a carnival-like courtroom provided the setting for the most abhorrent of arguments tendered to justify sadistic racism. Jurors excused premeditated slaughter.

What explains this? How deep into the depths of depravity must one dig to understand this?

Lasting lies. Once the law of double jeopardy shielded them, Bryant and Milam sold their murderous story to a publicity-hungry writer (William Bradford Huie) who sold it to Look magazine and hawked it to millions. That story, rife with lies, defined the history of the Till tragedy for decades. A capacious lie can have a long life.

No moral imperative can, however, be grounded in a lie, especially when that lie uproots the very possibility of understanding the past. Of course, past wrongs do not easily invite present reconciliations. That all-too-human failing helps to explain why there has been deep-seated resistance to fully and openly acknowledge the troubling truths of racial injustice in America. That mindset closets the evils of the past; sometimes, it even condemns those who expose such evils as being “un-American.”

Yet, if the true past remains concealed or denied, then the very idea of equal justice rings hollow, if only because so much of the past determines the future.

Hence the need to revisit the scene of the crime and what followed in court and thereafter. By that measure, the Emmett Till story has long remained an unfinished one. My book, Tragedy on Trial, was written to provide a comprehensive, critical, and corrective account of the trial and how it was thereafter portrayed to the nation.

The Psychology of Evil

Having just finished a book on the Emmett Till murder trial, I now find myself stepping back from the trees and exploring the psychological forest of it all. Sometimes, one needs distance to get perspective, to get some sense of the causes that give rise to such homicidal evil. To help situate my attention, I turn first to Simone Weil and her poignant 1939 essay “The Iliad or Poem of Force,” a work that focused on the frightening role of cruelty in Homer’s epic poem. My mind then runs to Hannah Arendt’s reflections on the banality of evil. Thereafter, more thoughts and more pondering.

As I teach a class on the murder trial, I try to think of the Till story anew, beyond the borders of history. And why? The answer hinges on the need to comprehend what seems incomprehensible, namely, the psychology of evil. Till’s murderers (shielded by a vile sheriff and cunning defense lawyers) transformed a 14-year-old boy into inert matter – a lifeless thing with no name. The psychology of their evil thus became manifest: they never viewed Emmett Till as a human being. Bigotry and intoxicating rage, followed by official wrongdoing, directed their psyches, which, in the process, first denied Emmett his dignity and then his life.

In 2023, President Joe Biden signed a proclamation establishing the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument in Mississippi and Illinois. The new monument is managed by the National Park Service. But know this: Justice seldom comes naturally; one must constantly struggle for it, lest the forces of evil prevail in ways that deprive us all of our humanity.

For more historical and current information, go to the Emmett Till Interpretive Center.