Sixty-five years ago, Ruby Bridges became the first Black child in the South to attend an all-white elementary school.

-

Winter 2025

Volume70Issue1

Editor's Note: Elisabeth Griffith is the author of two acclaimed books on women's history, Formidable: American Women and the Fight for Equality: 1920–2020 and In Her Own Right: the Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She has a PhD in history, and publishes a blog at Pink Threads on Substack.

On November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges walked through an angry crowd into a school emptied of other students.

“Driving up I could see the crowd, but living in New Orleans, I actually thought it was Mardi Gras,” Ruby recalled as an adult. “There was a large crowd of people outside of the school. They were throwing things and shouting, and that sort of goes on in New Orleans at Mardi Gras.”

Former United States Deputy Marshal Charles Burks later recalled, “She showed a lot of courage. She never cried. She didn’t whimper. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we’re all very very proud of her.”

Six years before, in May 1954, the US Supreme Court had declared unanimously that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. It ordered states to integrate “with all deliberate speed.” But Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, was met with “massive resistance” across the South. Senators raved about miscegenation and disrupting the social hierarchy. Mississippi’s Sen. James Eastland proclaimed that the South would not abide by or obey the ruling.

Governors ranted about states’ rights. Georgia’s Herman Talmadge vowed, “There will never be mixed schools while I am governor” and proposed closing all public schools. Virginia’s governor announced that school attendance was no longer mandatory. Parents who withdrew students would get funds for alternative schools. “White flight” academies sprung up across the region. In 1958 Virginia closed schools in Richmond, Charlottesville, and Warren County; Prince Edward public schools were shuttered for five years.

In 1956, Virginia Representative Harry Byrd circulated a Southern Manifesto, endorsing resistance to integrating any public spaces. It was signed by 19 Senators and 82 Representatives (97D, 4R) from eleven Confederate states.

Not every response was vitriolic. Tennessee Governor Frank Clement resisted demagogy. In 1955, 85 Black students attended two public schools in Oakridge. The event generated so little controversy and violence that a Knoxville News Sentinel headline read “Reporter Finds Little to Report as Negroes Attend Oak Ridge High.” Oakridge was run by the Atomic Energy Commission, part of the Manhattan Project, an “atomic city” full of scientists who did not grow up in the South. Report as Negroes Attend Oak Ridge High.” By 1959, only 6% of Black students in the South attended integrated schools.

Southerners used economic intimidation and mob violence to threaten Black parents. States criminalized peaceful protests. White resistance intensified, as the Little Rock Nine learned at Central High School in September 1957. Outside the school, they confronted snarling white parents; inside they confronted intimidation. The girls were beaten up in the bathroom, where the National Guard could not protect them. The Little Rock School Board sued the government to suspend implementation of Brown. In Cooper v. Aaron (1958), in a signed, unanimous, per curiam decision, the Supreme Court held that Arkansas officials were bound by Brown. More significantly, it declared Brown the supreme law of the land and binding on all the states, regardless of any state laws contradicting it.

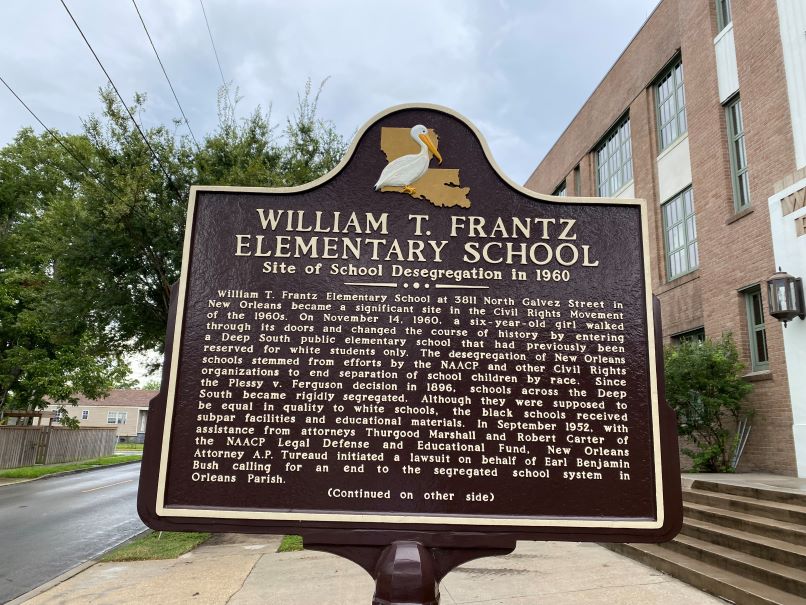

Judge J. Skelly Wright was a native of New Orleans, who taught history while attending Loyola law school at night. After serving in WWII, he served as a US Attorney in New Orleans. In 1948 President Truman named him to the Federal District Court of Louisiana. At age 38, he was the youngest judge on the federal bench, and the most liberal. When the Louisiana legislature refused to implement integration in 1959, the NAACP sued. Judge Wright ordered the integration of New Orleans public schools, to begin on November 14, 1960.

On Monday, November 14, six-year-old Ruby Bridges became the first Black child to integrate a New Orleans elementary school and the first in the South to attend an all-white elementary school. The daughter Abon and Lucille Bridges, a mechanic and Korean War veteran and a domestic worker, Ruby was born the year Brown was decided. She was one of six children who passed the required entrance examinations, which determined whether Black students could succeed in all-white institutions.

Proponents of integration believed that if the school year had already begun, white parents would be less likely to withdraw their children. They were wrong. Protests created security concerns, so every day her mother and US Marshals escorted her to William Frantz Elementary School. The first grader spent her first day in the principal’s office while white parents withdrew every child, close to 500 students. The next day Ruby was the only child in attendance. The only faculty member willing to teach her was Barbara Henry, newly arrived from Boston. Secluded in one classroom, neither missed a day of school.

Many white students were home-schooled; others slowly returned but the principal kept them away from Ruby. She was not allowed in the cafeteria or on the playground. She ate her bag lunch with her teacher, for fear of poisoning; she played inside for recess. She was accompanied to the bathroom by a Marshal. Mrs. Henry pressed the principal to let the students be together, eventually threatening to report him. He did not relent until the end of the year.

Ruby’s father lost his job, her mother was denied service at shops and her grandparents were evicted from their sharecropper’s shack in Mississippi. Solely dependent on donations, her parents eventually divorced. Harvard-educated child psychologist Robert Coles volunteered to help Ruby deal with how isolating and difficult the situation was, meeting with her once a week.

The Henrys moved back to Boston. In second grade, Ruby was no longer the “only.” Black enrollment increased year-by-year. Bridges graduated, became a travel agent, married and had four sons. After her brother was murdered, she adopted her four nieces, who attended William Franz school. In 1995, Dr. Coles wrote The Story of Ruby Bridges, which Disney made into a biopic. Paid as a consultant, Bridges earned enough to establish a foundation. She helped fund an arts program at her old school. After Hurricane Katrina caused significant damage, she lobbied for it to be protected on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1998 a statue of Ruby was unveiled in the school’s courtyard. Bridges, her mother, Barbara Henry and Charlie Burks, the last survivor of the four Marshals attended. The school has been expanded and renamed Akili Academy charter school but Henry’s classroom has been preserved.

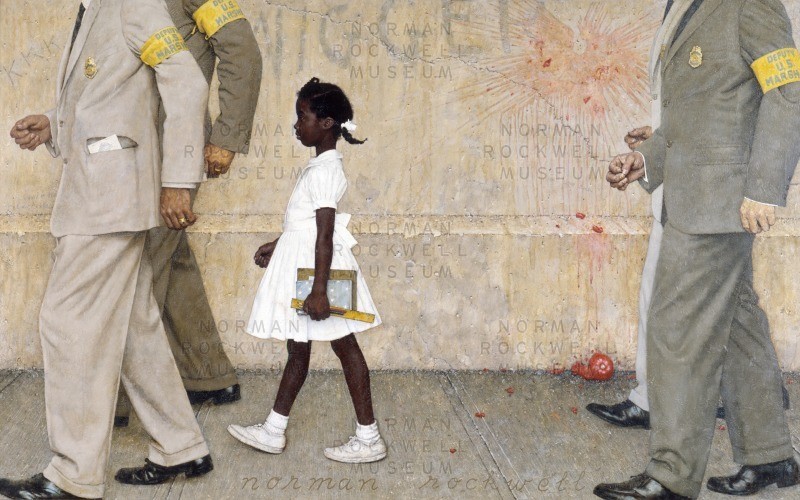

More famous was Norman Rockwell’s painting, The Problem We All Live With. It appeared illustrating a story in Look magazine in 1964. Subscribers were shocked and sent bags of letters, pro and con. The illustrator framed Ruby and the Marshals from a child’s perspective. In 2010 President Obama asked for the original to be hung in the White House and invited Ruby Bridges and Barbara Henry to view it outside the Oval Office. As an adult, Bridges served on the board of the Norman Rockwell Foundation.

Less well known are the three Black girls who integrated McDonough 19 Elementary School. Both schools were located in New Orleans Ninth Ward. Leona Tate, Tessie Provost and Gail Etienne were also age six. Later that week, an angry mob gathered outside a meeting of New Orleans school board. In September 1962, Catholic schools in the city integrated.

In 1962, President Kennedy named Judge Wright to the US Court of Appeals in Washington, following death threats and burning crosses. Southerners called him “Judas” Wright. His decisions would integrate schools, universities, buses, parks, sporting events and voter rolls. When Wright died in 1988, he was heralded as one of “the outstanding jurists in the nation’s history.”

Integrating public schools and facilities, much less American society, had not succeeded as proponents idealistically anticipated. The NAACP and the Justice Department kept bringing cases. In 1971 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (NC) Board of Education, the Supreme Court degreed that segregation must be “dismembered root and branch.” But the promise and complexity of that challenge were defeated by racially rooted economic inequality, housing patterns and deeply rooted social behavior. During their confirmation hearings, recent Republican nominees to the Supreme Court have hedged on whether Brown is a “super precedent,” which cannot be overturned.

When politicians and parents question what ought to be taught in schools, whether school children can absorb the harsh lessons of our nation’s past, that we need to protect them from those facts, I think about Ruby Bridges. And the enslaved children picking cotton or sold away from their families at her age. The poor children working in nineteenth century mills. The Indigenous children forcibly removed to government boarding schools. It was rare in our history for children to be protected from disease, death, fear and loss. We need to share their examples of resilience and courage. The “land of the free and home of the brave” needs to learn about our past, so we can move forward and do better.