As president, Dwight D. Eisenhower took a moderate position on many issues, believing that “good judgment seeks balance and progress.”

-

Winter 2025

Volume70Issue1

Editor’s Note: Steven Wagner is a professor of history and former head of the Social Science department at Missouri Southern State University. He is the author of two books on Ike, including Eisenhower for Our Time, in which portions of this essay appeared.

Early in his presidency, President Eisenhower wrote a letter to his good friend, retired Brigadier General Bradford Chynoweth, in which he explained his philosophy of the Middle Way.

Eisenhower’s pursuit of the Middle Way often put him at odds with the conservative wing of the Republican Party. This aspect of his presidency, however, was not appreciated by historians for nearly a generation. Early analysts of his administration took note of rivalries within the Republican party, but they didn’t identify the president as an active participant in them. This led them to conclude that he was a weak president and an ineffective party leader.

In the 1970s, revisionists began to challenge this interpretation. Making use of materials at the newly opened Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas, they suggested that, if Eisenhower had failed to solve the great problems of the day, it was not due to a lack of initiative on his part. Instead, it was the opposition within his party that stymied progress.

By the 1980s, historians considered Eisenhower’s fight with the party’s Old Guard one of the primary themes of his administration. Conservative opposition to the president’s initiatives in social welfare, farm and labor issues, public works, and many other issues revealed the right wing's fundamental disagreement with the president over the proper role of the federal government. Eisenhower’s position on these issues placed him squarely in the middle of the American political spectrum – to the right of liberals who had supported Franklin Roosevelt, and to the left of conservatives in his own party. Since he had no expectation of support from the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, his fight was with those on the hard right.

In American political culture, those who describe themselves as moderates are often portrayed as unwilling to take a stand, or lacking in political sophistication. This was not the case with Eisenhower. His “Middle Way” was a carefully considered political philosophy, an attempt to achieve a balance between the fears of conservatives and the demands of liberals. Despite his intentions, Eisenhower’s domestic policy proposals were often defeated by an unwitting alliance of conservatives who sought to limit the role of the federal government, and liberals who wanted the federal government to do more than he had proposed. Eisenhower hoped that his policies would change the direction of the Republican Party, but this was not to be.

Opposition from conservatives in his party made it necessary for Eisenhower to seek Democratic support for his legislative agenda. This was a difficult strategy in Eisenhower’s time, and increased political polarization in the years since has made it far less likely to succeed. Further complicating matters is the increased use of the filibuster by the minority party in the Senate. It is now assumed that 60 votes, the number required to defeat a filibuster, are necessary for nearly anything to pass in the Senate. So, even a president with a majority in both houses of Congress cannot count on legislative success. The unlikelihood of either party winning 60 seats in the Senate makes moderation and bipartisanship more important than ever.

Securing the nomination and the presidency

The 1952 Republican presidential nomination was a long-delayed battle between two factions for control of the party. An attempt to compete with Franklin Roosevelt’s immense popularity had led to a string of liberal Republican presidential nominations: Alf Landon (1936), a former Bull Moose Progressive who had endorsed many New Deal programs; Wendell Willkie (1940), a former Democrat who had voted for Roosevelt in 1932; and Thomas Dewey (1944 and 1948), who had supported the New Deal, but thought that Republicans could administer it more efficiently. These candidates’ failure to defeat Roosevelt, and Dewey’s particularly embarrassing loss to President Truman in 1948, had made party conservatives determined to run one of their own – Ohio senator Robert Taft – in 1952.

Eisenhower’s decision to enter the campaign for the Republican presidential nomination in 1952 was based, in large part, on his determination to prevent the nomination of Taft. His primary concern was Taft’s refusal to support NATO and U.S. participation in the collective security of Western Europe. He also believed that Taft’s conservative positions on domestic issues were out of step with the views of most Americans. Taft’s nomination, Eisenhower believed, would assure another Democratic victory and the breakdown of the two-party system, perpetuating the centralization of power in the federal government. Although he would have preferred to stay out of the campaign for the nomination, Eisenhower was ultimately convinced by his political advisers that doing so would assure Taft’s nomination.

On July 11, the convention voted on the presidential nomination. At the end of the first ballot, Eisenhower had 595 votes, Taft had 500, Governor Earl Warren of California had 81, former Minnesota governor Harold Stassen had 20, and Douglas MacArthur had 10.

Eisenhower was nine votes short of the number needed for nomination. Stassen released his delegates, prompting the head of the Minnesota delegation to rise and ask for the floor. Earlier, he had cast 19 votes for Stassen and nine votes for Eisenhower. He now wished to change his vote, giving all 28 to Eisenhower – more than enough for the nomination. The general had unexpectedly won a first-ballot victory.

Despite a hard-fought battle for the nomination, Eisenhower’s first instinct was to mend fences. Disregarding objections from some of his advisers, he phoned Taft and asked to meet him at his hotel. A surprised Taft agreed, and Eisenhower made his way across the street to the Conrad Hilton. The mood there was much different, with “the crowds noticeably sorrowful and even resentful.”

After Ike’s brief meeting with the senator, the two men spoke to reporters. “I want to congratulate General Eisenhower. I shall do everything possible in the campaign to secure his election and to help in his administration,” Taft said graciously.

Eisenhower responded in kind: “I came over to pay a call of friendship on a very great American. His willingness to cooperate is absolutely necessary to the success of the Republican party in the campaign and in the administration to follow.” Eisenhower’s statement “brought a chorus of cheers” from Taft supporters. This was a welcome change from the “mixture of cheers and boos” that had greeted his arrival.

Eisenhower won the Republican nomination by a slim margin, but his victory in the general election was a landslide by any measure. In the Electoral College, he defeated the Democratic candidate, Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, 442-89. In the popular vote, he got 34 million votes (55 percent) to Stevenson’s 27.3 million (44.5 percent). A record 62 million Americans had voted (63.3 percent of eligible voters). Of particular note was Eisenhower’s success in the South, where he won four states in the former Confederacy, more than any Republican since the end of Reconstruction.

The politics of the “Middle Way”

Republican success in the general election masked intense factionalism within the party. Eisenhower would be the first Republican president in 20 years, but he was at odds with a growing faction of his own party. Conservatives, who had a considerable base of power on Capitol Hill, were eager to overturn a generation of liberal domestic policies and internationalist foreign policies.

Central to the factional differences was the role of the federal government. Conservatives preferred free enterprise and a major emphasis on individual initiative to major federal programs and the taxes necessary to support them. When government action was unavoidable, they favored state or local control in areas where the federal government had no explicit constitutional power. In foreign policy, conservatives had not reverted to the isolationism they espoused before World War II, but they had not completely converted to internationalism, either. They virulently opposed communism, but did not see the benefits of collective security alliances or foreign aid programs.

Eisenhower, despite some of his campaign rhetoric, supported a more active role for the federal government in both domestic and foreign policy. He supported the continuation, and in some cases, the expansion, of popular New Deal programs. When new programs were necessary, however, he supported those that would allow the federal government to act as a catalyst for change, without adding significantly to its responsibilities.

This would allow the national government to look after the welfare of individuals and still maintain fiscal responsibility. It was, according to the new president, “a liberal program in all of those things that bring the federal government in contact with the individual,” but conservative when it came to “the economy of this country.” Somewhat less enthusiastically, he also supported federal legislation that would protect the economic interests of farmers and organized labor, and the civil rights of black people. On foreign policy issues, Eisenhower was a committed internationalist.

To conservatives, the promotion of an active government, both at home and abroad, seemed like a mere continuation of the Democratic policies of the previous 20 years, but that was not Eisenhower’s intention. The key to understanding how he distinguished his policies from those of liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans is his philosophy of the “Middle Way.” After he had secured the Republican nomination, he began to speak more frequently about this approach. In an October campaign speech, he warned his audience about the dangers of going too far to the political left or right. Those on the left, he said, believed that people were “so weak, so irresponsible, that an all-powerful government must direct and protect” them. The end of that road, he warned, was “dictatorship.” On the right were those “who deny the obligation of government to intervene on behalf of the people, even when the complexities of modern life demand it.” The end of that road was “anarchy.” To avoid those extremes, he said, “government should proceed along the middle way.”

Many of Eisenhower’s domestic-policy proposals provide examples of this philosophy. Conservatives referred to his proposals regarding social welfare as “creeping socialism,” but he believed that, by addressing the problems that threatened American society, his programs would stem – not encourage – the impetus toward socialism. Eisenhower saw programs such as Social Security as a safety net, “a floor over the pit of personal disaster in our complex modern society.” Unlike socialism, however, they did not create a “ceiling” that limited individual initiative and industry. They did not interfere with “the right ... to build the most glorious structure on top of that floor.”

The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare

Searching for the “Middle Way” in the field of social welfare, Eisenhower attempted to provide for the general welfare, as called for in the Constitution, without taking on the enormous financial burdens of an ever-expanding welfare state or significantly encroaching on the responsibilities of local government. He was continually frustrated when his moderate programs were opposed by conservative Republicans who were anxious to overturn the legacy of the New Deal, and by liberal Democrats who were unwilling to settle for less federal intervention than they would like. Eisenhower’s only first-term social-welfare success came in Social Security, where a program was already in place. His initiative in health insurance, which required a new program, had failed at the hands of conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats. Leading the way in the formation of policy in this field was the new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

During the 1952 campaign, Eisenhower promised to study the problem of federal waste and mismanagement and, if elected, make recommendations for government reorganization. He asked Nelson Rockefeller, who had served as FDR’s Assistant Secretary of State, to head a new Special Committee on Government Organization (SCGO). The other members of the committee were the president’s brother Milton, president of Pennsylvania State University, and Arthur Flemming, president of Ohio Wesleyan University and the former director of the Office of Defense Mobilization.

The SCGO had a broad mandate to study and recommend changes in the organization and activities of the executive branch in order to promote economy and efficiency. Eisenhower’s “Middle Way” served as the blueprint for the committee’s recommendations. “We have been guided by your own expressed determination to avoid any actions which tend to make people ever more dependent upon the government, and yet to make certain that the human side of our national problems is not forgotten."

The first recommendation of the SCGO was to create a new cabinet-level department to absorb the functions of the Federal Security Agency (FSA). This agency, created by Franklin Roosevelt in 1939, had 38,000 employees representing the Social Security System, the Food and Drug Administration, the Public Health Service, and the Office of Education. Despite a budget of $4.6 billion, the FSA lacked cabinet status. The creation of a new department, the committee believed, would be “an important milestone on the road to social progress,” making clear that the Republican Party recognized that the government’s responsibilities embodied by the FSA were permanent, providing “an excellent example of the beneficial functioning of our two-party system.”

On March 12, 1953, Eisenhower delivered a special message to Congress requesting approval of the creation of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). Republicans had opposed President Truman’s attempts to elevate the FSA to cabinet status in 1949 and 1950. For many Republicans, health and education were not legitimate areas of federal concern. Placing the Public Health Service and the Office of Education under the supervision of a cabinet department, particularly one that was oriented toward welfare, would only strengthen the federal bureaucracy’s claim to legitimacy in these areas.

The SCGO overcame these objections through decentralization. The plan for the HEW did not place all of the department’s powers in the hands of the secretary. The functions of the Public Health Service and the Office of Education, for example, remained in those agencies, which were subordinate divisions of the new department; the secretary would have only supervisory control.

There was very little opposition from either party to the creation of the HEW. The measure won bipartisan support, and Eisenhower signed the bill creating this department on April 11, 1953.

Although Republican congressmen participated in the creation of the HEW, they did not see themselves as acquiescing in the creation of a permanent "welfare state." Rather, they were admitting that Social Security, the Food and Drug Administration, and the other components of the HEW were an accepted and popular part of American society. Only the most conservative Republicans still favored their elimination.

Oveta Culp Hobby, who Eisenhower had appointed head of the FSA, became the HEW’s first secretary. Hobby was a registered Democrat from Texas, but she had endorsed Eisenhower for president on the front page of the Houston Post, which she and her husband owned. Her appointment would reward the many southern Democrats who had crossed over to vote for Eisenhower, and would solidify the bipartisan credentials of the new department.

Nelson Rockefeller would serve as undersecretary. He believed that it was important for the Republican Party, which was so often associated with preserving the status quo, to demonstrate that the gains of the New Deal era had bipartisan support and would be not only retained, but improved upon by the Republican Party. “A Republican administration couldn’t be seen to be trying to turn back the clock,” he later recalled.

As Eisenhower had asserted in his campaign statements, he was definitely not in favor of retrogression. “I believe that the social gains achieved by the people of the United States, whether they were enacted by a Republican or a Democratic administration, are not only here to stay, but are to be improved and expanded,” he argued. “Anyone who says it is my purpose to cut down Social Security, unemployment insurance, and to leave the ill and aged destitute, is lying.”

Despite these general principles, however, it was unclear to Ms. Hobby and Mr. Rockefeller where Eisenhower stood on the specific domestic policy debates that concerned the HEW.

Expanding Social Security

Among the issues up for immediate consideration was the expansion of Social Security. Throughout the campaign, Eisenhower had promised, if elected, to extend coverage to groups that were not eligible for benefits, including farmers, domestic workers, and self-employed professionals such as lawyers and doctors. He repeated this pledge in his first State of the Union address on February 3, 1953.

What was unclear was whether he favored an expansion of the system or the “pay-as-you-go” plan that the 1952 Republican platform identified as deserving a “thorough study.” Under the existing system, benefits for the elderly were paid by using the same framework that had been established by the Social Security Act of 1935. This created a federally operated, compulsory, old-age pension program. Qualified workers paid for the program with a payroll tax matched by their employer. Proceeds were placed in a federal trust account. At the age of 65, those workers became eligible for monthly payments relative to the amount they had contributed to the program over the years.

The pay-as-you-go plan, promoted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and endorsed by many conservatives, was an attempt to create a universal-coverage, old-age pension funded by existing revenues. Under this plan, all employed workers would be subject to the existing payroll tax, and all elderly people would be eligible for a flat-rate pension, regardless of their employment history. The cost of starting up the program would be paid from the in-place trust account, and all future benefits would be paid from that year’s contributions. In his 1953 budget message, the president had shown interest in the pay-as-you-go model.

The HEW, however, recommended expanding the system based on the existing model. Hobby and Rockefeller argued that, under the financing system as it then was, such as the one proposed by the Chamber of Commerce, business interests and others seeking lower taxes would pressure Congress to keep the program’s costs down, thus preventing future benefits from keeping pace with inflation. Eliminating the trust-fund aspect of Social Security, they argued, created the possibility that it could be dismantled by future politicians who did not want the responsibility of collecting the taxes to pay for it.

On November 20, 1953, Hobby and Rockefeller outlined the HEW’s proposal for expanding the system to Eisenhower and the cabinet. This meeting is often credited with convincing Eisenhower to abandon pay-as-you-go plans and to endorse expanding the system as it was. Other evidence, however, suggests that, by this time, Eisenhower may have already made up his mind.

On October 7, 1953, in a letter to the financier Edward Hutton, Eisenhower anticipated the HEW’s contention that eliminating the trust fund would ultimately lead to the dismantling of the system. “It would appear logical to build upon the system that has been in place for almost 20 years,” he wrote, “rather than embark upon the radical course of turning it completely upside-down and running the very real danger that we would end up with no system at all.”

On January 14, 1954, he submitted the HEW plan to Congress. He followed up with several public speeches. “We want to preserve and strengthen its (the Social Security System’s) reliance on a contributory system, in which workers and their employers share the obligation to make payments,” Eisenhower said the next month in New York City. “Equally firm in our thinking is the belief that the benefits paid to workers should bear a definite relation to their earnings in their years of activity. To scrap either of these underlying principles would move the system in the direction of charity, and undermine the social-insurance concept.”

Although many Republicans still preferred a pay-as-you-go scheme, most were reluctant to vote against expanding one of government’s most-popular programs. The administration’s proposal was, therefore, overwhelmingly approved by both houses, and Eisenhower signed it into law as the Social Security Amendments Act on September 1, 1954. This brought nearly 10,000,000 additional people under the protection of Social Security, and included self-employed professionals and small farmers, agricultural and domestic workers, employees of state and local governments, and U.S. citizens employed outside the country. Another important provision was a 16-percent increase in benefits.

The New York Times proclaimed, “In strictly human terms, this was perhaps the most significant achievement of the administration in the 1954 session of Congress.” Not only had the new Republican presidential administration refused to dismantle one of the New Deal’s most-popular programs; under Eisenhower’s leadership, it had expanded it.

Health Reinsurance

During the 1952 campaign, Eisenhower continually stated his opposition to any form of federal, compulsory health insurance, such as that proposed by President Truman in 1949 and 1950. These plans he had condemned as examples of “creeping socialism.” He believed that plans offered by commercial and non-profit insurance carriers, along with locally administered programs for those who were unable to afford insurance, could best meet the needs of the American people.

“Any move toward socialized medicine is sure to have one result,” Eisenhower said. “Instead of the patient getting more and better medical care for less, he will get less and poorer medical care for more.... We must preserve the completely voluntary relationship between doctor and patient.” Eisenhower’s stand clearly reflected the Republican Party line as stated in its 1952 platform.

Once again, Rockefeller played an important role in Eisenhower’s pursuit of the “Middle Way.” The answer to bringing adequate medical care within the means of all Americans, he argued, was not to institute federally sponsored health insurance, but to provide incentives for health-insurance companies to expand their coverage. Rockefeller came up with a plan to do this, without committing the federal government to a predominant role.

The plan was known as health reinsurance. Under this plan, the federal government would insure commercial and non-profit insurance companies against “abnormal losses” associated with offering policies to individuals who were not adequately covered by health insurance, or for costs not widely covered by insurance policies. The plan would not pay benefits to individuals or reimburse companies for benefits paid to any individual policy-holder. Nor would it reimburse companies for their overall losses. Rather, insurance companies would propose that a particular type of policy be eligible for reinsurance.

Despite Eisenhower’s personal backing, on July 13, 1954, the House rejected the health-reinsurance plan by a vote of 238 to 134. Seventy-five of those members who voted against the bill were Republicans. Eisenhower did not take the defeat lightly. He asked his press secretary, James Hagerty, to get a breakdown of the roll-call vote and bring him the names of Republicans who had voted against it. “If any of those fellows who voted against that bill expect me to do anything for them in this campaign, they are going to be very much surprised,” Eisenhower told him, referring to the 1954 congressional election campaign. This was a major part of our liberal program, and anyone who voted against it will not have one iota of support from me.”

The next day, he went public with his criticism: “The people who voted against this bill just don’t understand what are the facts of American life,” Eisenhower told the White House press corps. “There is nothing to be gained, as I see it, by shutting our eyes to the fact that all of our people are not getting the kind of health care to which they are entitled.”

Eisenhower did not limit his anger to House members. He blamed the American Medical Association for waging a campaign to portray the bill as socialized medicine. When Senate majority leader William Knowland tried to defend the AMA position at a legislative leaders’ meeting, Eisenhower cut him off: “Listen, Bill. We said during the campaign that we were against socialized medicine.... As far as I’m concerned, the American Medical Association is just plain stupid. This plan of ours would have shown the people how we could improve their health care and stay out of socialized medicine.”

Health reinsurance was an excellent example of Eisenhower’s so-called “Middle Way. “ By using government resources to encourage the insurance industry to expand health coverage, it would act as a catalyst for improving the system, without assuming primary responsibility for it. He vowed to continue the fight: “I am trying to redeem my campaign promises, and I will never cease trying. This is only a temporary defeat; this thing will be carried forward as long as I am in office.” But his administration’s attempts to revive the reinsurance plan in the 84th Congress failed.

Eisenhower Republicanism

HEW Secretary Hobby blamed congressional Democrats for the failure of Eisenhower’s social-welfare proposals. She believed that they were “attempting to ensure that this administration got no glory for any legislative accomplishments in this field.”

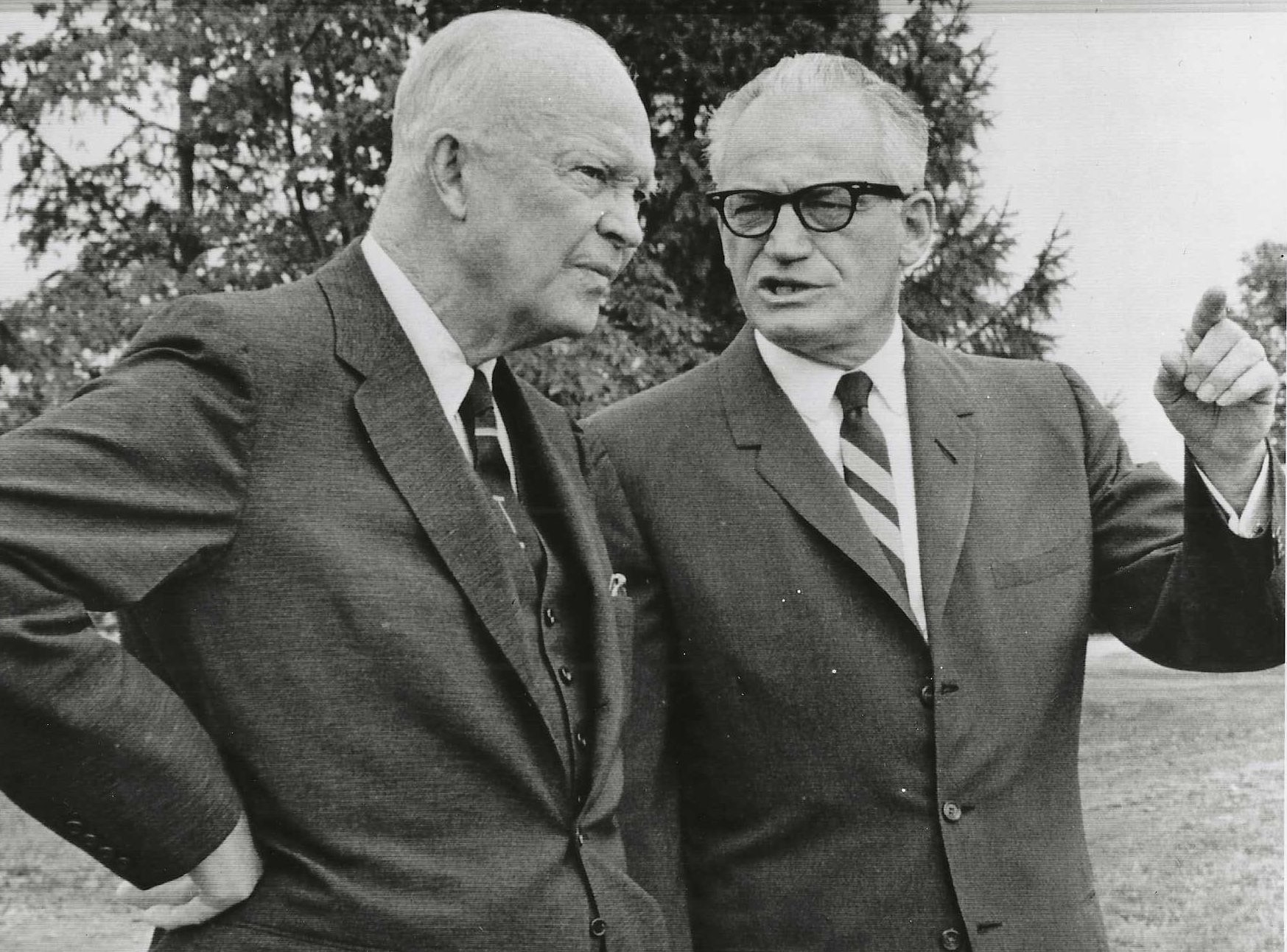

Eisenhower, expecting no help from Democrats, blamed conservatives in his own party. Many of those Republicans were, indeed, unhappy with the policies proposed by their president. Senator Barry Goldwater, who became the leading conservative spokesman after the death of Robert Taft in July 1953, wrote: “It is obvious that the administration has succumbed to the principle that we owe some sort of living ... to the citizens of this country, and I am beginning to wonder if we haven’t gone a lot further than many of us think on this road we happily call socialism.”

Goldwater later recalled that he was “deeply disappointed when the Republican administration under President Eisenhower, with a working majority in both houses of Congress, proposed to continue the old New Deal, Fair Deal schemes, offering only a modification in scale and no change in direction.”

The president could not even get a word of support from his brother Edgar, who wrote that many of his friends could see “very little difference between the policy of your administration and that of the former administration.” Ike replied: “Should any political party attempt to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and to eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do these things.... Their number is negligible, and they are stupid.”

Eisenhower’s experiences in the field of social policy gave added meaning to a remark he had made to his secretary, Ann Whitman: “You don’t have very many friends when you’re walking a decent middle way.”

As he contemplated whether to retire at the end of his first term, he feared that the conservative wing would capture the party in his absence. “If they think they can nominate a right-wing, Old Guard Republican for the presidency, they’ve got another thought corning,” he told press secretary James Hagerty. “I’ll go up and down this country, campaigning against them. I’ll fight them right down the line.” Eisenhower believed that the political thinking of the party’s right wing was completely out of step with the times. “I believe this so emphatically,’ he wrote in his diary, “that I think that, far from appeasing or reasoning with the dyed-in-the wool reactionary fringe, we should completely ignore it and, when necessary, repudiate it. They are the most ignorant people now living in the United States.”

After a disappointing mid-term election in 1954, Eisenhower said that, aside from keeping the world at peace, he had just one purpose for the next two years: “to build up a strong, progressive Republican Party in this country. If the right wing wants a fight, they’re going to get it. If they want to leave the Republican Party and form a third party, that’s their business, but, before I end up, either this Republican Party will reflect progressivism, or I won’t be with them anymore.”

In private conversations, he contemplated leaving the party. “If the right wing really recaptures the Republican Party,” he told his friend Gabriel Hauge, “there simply isn’t going to be any Republican influence in this country within a matter of a few brief years.” After one legislative defeat, he discussed with White House Chief of Staff Sherman Adams whether he belonged in the party. He thought that perhaps the time had come for a new party that would accept a leadership role in world affairs, a liberal stand on social-welfare policy, and a conservative stand on economic matters.

After a talk with the president on this subject, his friend William Robinson, Chairman of Coca-Cola, wrote in his diary that Eisenhower had told him that, if the die-hard Republicans fought his program too hard, he would have to organize a third party. Later, according to Robinson, Eisenhower smiled and admitted that this was an impractical alternative, but that he was not willing to give it up entirely.

In Eisenhower’s attempt to revitalize the party, many of his friends and advisers urged him to use the term “Eisenhower Republicanism:’ but he was against it. He agreed that personalizing the effort would be the easiest and perhaps the most successful way to reform the party, but he feared that, if the effort revolved around him, then the movement would collapse in his absence. “The idea,” he thought, “was far bigger than any one individual.” He wanted to broaden the party’s appeal, not personalize it.

Although he would later take up the term “modern Republican,” Ike resisted the use of any descriptive adjectives to define his wing of the party. His opinion on this issue is apparent in a letter to his brother Edgar, who had referred to himself as the only “real Republican” in the family: “I am a little amused about this word ‘real’ that, in your clipping, modifies the word ‘Republican. I assume that Lincoln was a real Republican – in fact, I think we should have to assume that every president, being elected leader of the party, is a real Republican. Therefore, the president’s branch of the party requires, for its description, no adjective whatsoever.” Rather, he believed, “the splinter groups, which oppose the leader, would be the ones requiring the descriptive adjectives.”

Eisenhower was convinced that the only way for the Republican Party to remain a vital force in American politics was for it to take a liberal approach to its domestic problems: “This party of ours,’ he explained to James Hagerty, “will not appeal to the American people unless they believe that we have a truly liberal program.” He was convinced that, “unless Republicans make themselves the militant champions of the Middle Way, they are sunk.”

His attempt to find such a way for social-welfare policy was only partially successful. Like the majority of Americans, he accepted the contributions made by Presidents Roosevelt and Truman to the general welfare. In these areas, where programs were already in place, he sought to strengthen and expand upon them. In this, he was successful. His creation of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare gave cabinet status to the Federal Security Administration, and his amendments to the Social Security Act gave more than 10,000,000 additional workers access to retirement insurance.

Where new programs were necessary, however, Eisenhower was far less successful. His proposal for health reinsurance was an attempt to use the resources of the federal government to encourage progress in this area. He was seeking balance, a middle path between conservatives, who believed that health care was outside the scope of federal responsibility, and liberals, who would have preferred that the federal government accept primary responsibility for it.

He ultimately failed in his attempt to change the direction of the Republican Party. This failure was primarily due to his belief that the change he desired could be achieved on the strength of his policies alone. He believed so strongly in the what he called the Middle Way that he couldn't understand why others did not. For eight years, he battled conservative opposition to his programs in Congress, which rarely gave him the opportunity to show what they might do. Without a body of successful domestic legislation, his moderate strategy could never achieve the status of a New Deal or Fair Deal or change the direction of the party.

Eisenhower’s inability “to build up a strong, progressive Republican Party” has relevance in our time. The defeat of liberalism within his party, followed by the defection of conservative, mostly southern Democrats to the Republican Party in the decades that followed, left the country with a rigidly ideological two-party alignment.

Intensifying political polarization has made Eisenhower’s ideal strategy even less likely to succeed in 2024. The Pew Research Center recently concluded that, in Congress, “Democrats and Republicans are farther apart ideologically today than at any time in the past 50 years.” Both parties have moved away from the ideological center, with Democrats becoming “somewhat more liberal” and Republicans becoming “much more conservative.”

By Pew’s account, this leaves only two dozen moderate members of Congress amenable to bipartisan legislative negotiations. Participating in such cooperative activity, however, leaves members from both parties open to primary challengers.

Further complicating matters is the proliferation of filibusters in the Senate. In Eisenhower’s time, when the use of the filibuster required the minority party to hold the Senate floor during debate, filibusters were relatively rare. Since 1970, however, the minority party can impose a filibuster by merely submitting a letter to the chair. Initially, this rule change led to only a moderate increase in filibusters. After 2008, from the beginning of the Obama administration, increased partisanship and ideological polarization caused a dramatic increase.

It is now assumed that 60 votes are necessary for nearly anything to pass in the Senate. So, even a president with a majority in both houses cannot count on legislative success. Given the difficulty of one party achieving a super-majority, the need for moderation and bipartisanship has never been more apparent.