Charles Lindbergh and the isolationists of American First opposed Lend Lease and Roosevelt’s attempts to prepare for possible war in Europe.

-

Fall 2024

Volume69Issue4

Editor’s Note: Paul M. Sparrow is the former Director of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. He has recently published Awakening the Spirit of America: FDR's War of Words With Charles Lindbergh — and the Battle to Save Democracy, which tells the dramatic story of how Roosevelt prepared the nation for the fight to save democracy at a time when most Americans opposed intervention, and the America First movement fought aggressively to thwart his efforts. Mr. Sparrow provides an adaptation from his fascinating book in the essay that follows.

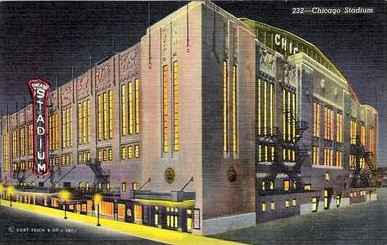

Late in the afternoon of April 17, 1941, pedestrians began streaming through Chicago’s downtown, heading for the stadium at the corner of Erie and West Madison. When completed in 1929, Chicago Stadium had been the world’s largest indoor arena, home ever since to the Second City’s beloved Blackhawks. Tonight, the stadium was hosting a rally booked by the America First Committee and featuring that group’s newest spokesperson, Charles Lindbergh. After months of keeping America First at arm’s length, the celebrity isolationist had finally reasoned that the nation’s many such entities ought to unite under a single banner — the banner of America First.

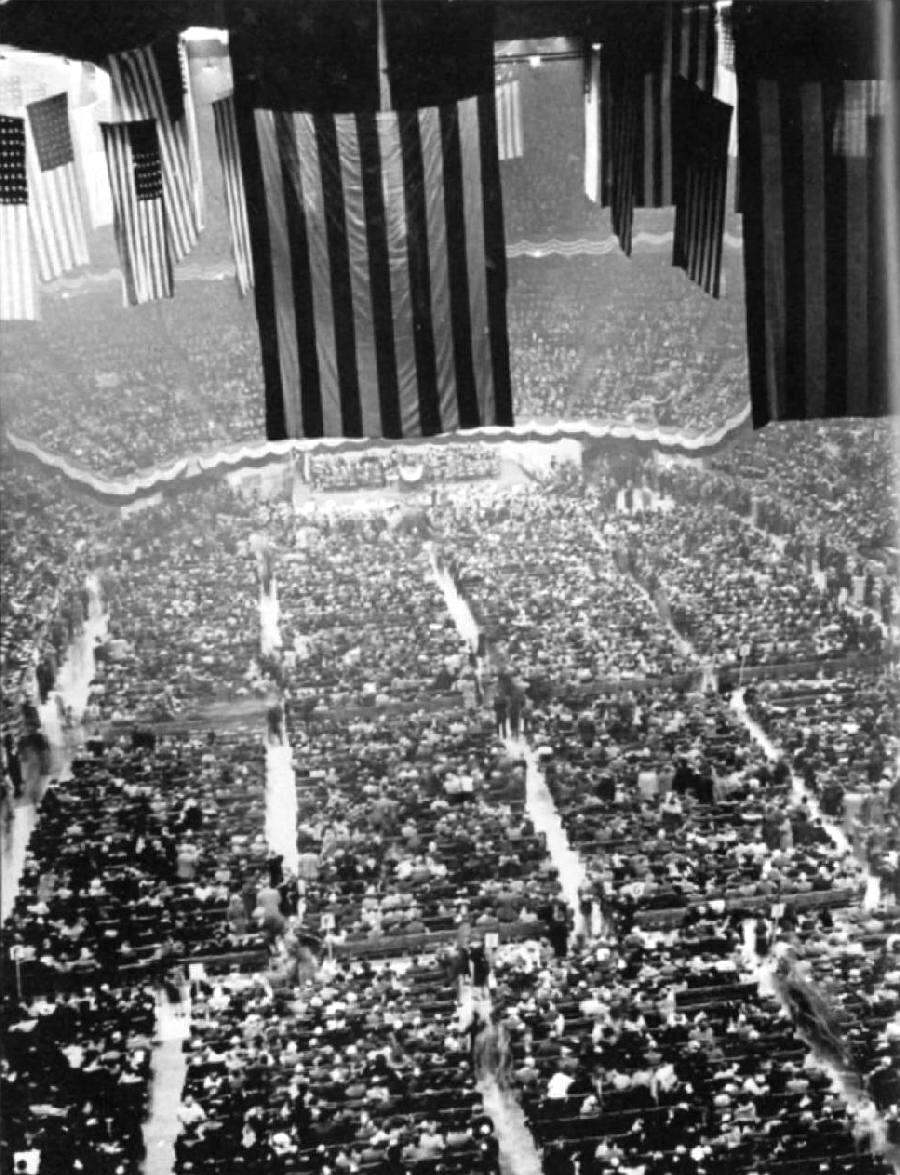

More than 10,000 people had crammed into the enormous hall; loudspeakers outside reached another 4000 milling partisans. From the high vaulted ceiling hung more than 50 giant American flags and enormous loops of red, white, and blue bunting. Onstage stood portraits of George Washington and large signs reading “Defend America First.” Charles Lindbergh came to the podium to ecstatic cheers and applause. Once the ovation dwindled Lucky Lindy explained why he had finally allied publicly with the event’s sponsor.

“The America First Committee is a purely American organization formed to give voice to the hundred odd million people in our country who oppose sending our soldiers to Europe again,” Lindbergh said. “Our objective is to make America impregnable at home, and to keep out of these wars across the sea. Some of us, including myself, believe that the sending of arms to Europe was a mistake — that it has weakened our position in America, that it has added bloodshed in European countries and that it has not changed the trend of the war.”

The audience repeatedly screamed its support as if with one voice, interrupting him 31 times, according to the Chicago Tribune, whose publisher Robert McCormick was helping to finance America First.

“This war was lost by England and France even before it was declared, and that it is not within our power in America today to win the war for England,” Lindbergh went on. A few hours earlier, London had come under one of the Luftwaffe’s most devastating attacks so far, as 46,000 incendiary bombs and 350 tons of explosives fell on the capital city. Among targets severely damaged was St. Paul’s Cathedral.

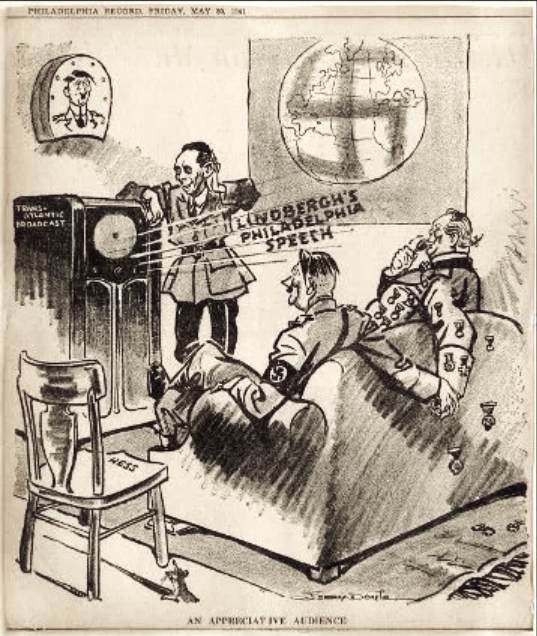

Having joined America First, Lindbergh committed himself to fighting Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease program at every opportunity. Six days after his coming-out party in Chicago, he headlined an America First rally at the Manhattan Center on West 34th Street in New York. More than 10,000 souls packed the former opera house, and millions more coast to coast tuned in on radio. The once self-effacing Lindbergh took the stage with a swagger akin to that of Germany’s and Italy’s dictators. The crowd roared approval for three minutes, breaking into chants of “We Want Lindy!” That night’s audience included members of the American Bund, fanatics from Father Coughlin’s Christian Front, and other Hitler supporters. The New York Times reported that “German accents were numerous” in the crowd.

Senator Burton Wheeler gave a rousing anti-Roosevelt speech, claiming the president was in thrall to “jingoistic journalists and saber-rattling bankers in New York.” When the cavernous hall finally quieted, Lindbergh gave his fellow isolationists the rhetorical red meat they craved.

“I know I will be severely criticized by the interventionists in America when I say we should not enter a war unless we have a reasonable chance of winning,” he said. “When history is written, the responsibility for the downfall of the democracies of Europe will rest squarely upon the shoulders of the interventionists who led their nations into war uninformed and unprepared. With their shouts of defeatism, and their disdain for reality they have already sent countless thousands of young men to death in Europe.”

Men standing near the front shouted out Lindbergh’s name and raised the “Sieg heil” salute. Repeating his thinly veiled reference to the myth that Jews controlled the media, he brought the crowd back to its feet.

“We have been led toward war by a minority of our people,” Lindbergh declared. “This minority has power. It has influence. It has a loud voice. That is why the America First Committee has been formed — to give voice to the people who have no newspaper, or newsreel, or radio station at their command; to the people who must do the paying, and the fighting, and the dying, if this country enters the war.”

Inside the hall people were cheering and applauding. As in Chicago, thousands more listened on loudspeakers outside. But there were also protesters by the hundreds. Police on horseback struggled to keep the plaza in front of the building clear and to separate the rival crowds. Clogged streets brought traffic to a standstill.

The protest was the doing of Friends of Democracy, a watchdog group whose leader, Leon Birkhead, had warned Lindbergh that America First was being manipulated by Hitler’s propaganda machine. The pro-Roosevelt magazine PM called the event a “liberal sprinkling of Nazis, Fascists, antisemites, crackpots, and just people, in which the just people seemed out of place.”

As the rally was beginning, the Friends of Democracy and allies marched along West 34th Street. In the lead was a young woman and ten men carrying pro-Lend-Lease placards. America Firsters began booing, then rushed their opponents, knocking people down and tearing up their signs as police officers stood by watching. It was an ugly scene, and one that would be repeated as the “great debate” grew in intensity in the coming months. With the popular American hero now on board, America First Committee membership ballooned from 300,000 to 800,000.

During this tense period in 1941, FDR confronted isolationists, fascists, and anti-immigrant politicians with what he thought was a better vision for the world, built on the founding principles of the United States with a commitment to fight for freedom.

After Hitler plunged Europe into the chaos of World War II and the British Empire teetered on the brink of collapse, the future of democracy would come to rest on one man’s shoulders. Franklin Roosevelt battled fierce resistance as he sought to provide support for Great Britain in its time of desperate need. The handsome and world-famous aviator Charles Lindbergh emerged as Roosevelt’s nemesis and led the isolationist opposition to the president’s efforts. Lindbergh spoke for many, and his allies included FDR’s own Ambassador to Great Britain Joseph Kennedy, media titan William Randolph Hearst, and automobile tycoon Henry Ford.

President Roosevelt had his own allies, chief among them Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The two men forged a transatlantic partnership often hailed as the most important alliance in American history. Roosevelt’s team of advisors and writers included Harry Hopkins, a New Dealer who became the president’s closest advisor; Judge Samuel Rosenman who started helping FDR with his speeches in the late 1920’s and the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Robert Sherwood who added poetry and passion to Roosevelt’s prose. And, of course, his wife Eleanor Roosevelt, the most influential first lady in American history. All helped him in his fight for the soul of America and the battle between democracy and fascism.

At a press conference two days after Lindbergh’s New York appearance, an Evening Star columnist asked FDR, “Mr. President, how is it that the Army, which needs now distinguished fliers, etc. has not asked Colonel Lindbergh to rejoin his rank as Colonel?”

Until then, Roosevelt had not made any public statements directly mentioning Lindbergh. His response may have been off the cuff, but it bore the marks of advance consideration. Press secretary Steve Early might even have planted the question. Invoking the Civil War, FDR specifically referenced Clement Vallandigham, a leader of Northerners who opposed Abraham Lincoln’s efforts to preserve the Union and were known as “Copperheads.”

“Well, Vallandigham, as you know, was an appeaser,” Roosevelt said, explaining his reference. “He wanted to make peace from 1863 on because the North ‘couldn’t win,’” FDR went on. “Once upon a time there was a place called Valley Forge and there were an awful lot of appeasers that pleaded with Washington to quit, because he ‘couldn’t win.’ Just because he ‘couldn’t win.’ See what Tom Paine said at that time in favor of Washington keeping on fighting.”

“Wasn’t it ‘These are the times that try men’s souls’?” shouted Earl Godwin.

“Yes, that particular paragraph,” the president replied. “In fact, I read it in the Post or the Star the other day.”

“Were you still talking about Mr. Lindbergh?”

“Yes,” Roosevelt answered, hoisting his chin and flashing his disarming smile.

Bristling at FDR’s characterization, Charles Lindbergh immediately wrote the president a letter made public. “I had hoped that I might exercise my rights as an American citizen, to place my viewpoint before the people of my country in time of peace, without giving up the privilege of serving my country as an Air Corps officer in the event of war,” he told Roosevelt. Complaining that since his commander in chief had clearly implied “that I am no longer of use to this country as a reserve officer,” he was resigning his Air Corps Reserve commission. Lindbergh sent a formal resignation letter to Secretary of War Henry Stimson.

The Roosevelt-Lindbergh feud became a running media narrative. The New York Times chastised both in an editorial: “President Roosevelt spoke impetuously last Friday when he went back three quarters of a century into the bitterness of the Civil War to find a disparaging epithet for Charles A. Lindbergh. Mr. Lindbergh in turn shocked those who believe him to be a loyal American — though a sadly mistaken one — by his petulant action in relinquishing his commission in the Army Air Corps reserve.”

Lindbergh gave fiery speeches in St. Louis and Minneapolis, claiming over and over that England could not win the war no matter how many planes and ships the U.S. provided, and that he would continue to speak his truth no matter the consequences.

On May 23, 1941, Lindbergh returned to New York City for another America First rally. Demand for tickets was so intense that the committee booked the enormous Madison Garden. The historic hall filled to its listed capacity 22,000, with another 10,000 outside clamoring to get in. Joining Lindbergh onstage was Senator Wheeler, fast becoming the leading elected voice opposing aid to the Allies.

Again, a sizable number of those present had direct ties to pro-Nazi groups. When Lindbergh rose to speak, a tide of chants and cheers greeted him. Tricolor bunting, displays of Old Glory, and abundant expressions of patriotic passion camouflaged the anger, hatred, and anti-semitism roiling just below the surface.

Without naming his target, Lindbergh attacked President Roosevelt repeatedly.

“We lack only a leadership that places America first — a leadership that tells what it means and what it says,” he said. “Give us that and we will be the most powerful country in the world. Give us that and we will be so united that no one will dare to attack us. We have been led toward war against the opposition of four-fifths of our people.”

Harkening to the previous autumn’s election, Lindbergh and Wheeler contested the legitimacy of Roosevelt’s victory. They claimed he had invalidated his victory by lying that he would not send American boys to fight in Europe.

“We had no more chance to vote on the issue of peace and war last November than if we had been in a totalitarian state ourselves,” said Lindbergh. “We in America were given just about as much chance to express our beliefs at the election last Fall, as the Germans would have been given if Hitler had run against Goring.”

Comparing Roosevelt and Willkie to Hitler and his field marshal marked a dramatic escalation in the virulence of Lindbergh’s critique. The crowd loved it, booing and hissing at his every mention of “leadership” as he worked his way toward an ominous warning.

“From every section of our country, a cry is rising against this war,” Lindbergh. He demanded support for America First and opposition to Roosevelt. “Our American ideals, our independence, our freedom, our right to vote on important issues, all depend on the… the action we take at this time.”

A week later, the president was wheeled into the East Room for a Pan-American Day broadcast before a formally dressed crowd of ambassadors, ministers, and their families. In his remarks, Roosevelt addressed the issue of Germany controlling shipping lanes vital to Britain and the United States. “The blunt truth is this,” Roosvelt told the crowd. “The present rate of Nazi sinkings of merchant ships… is more than the combined British and American output of merchant ships today.”

On June 20, the clear, warm summer air offered a perfect night for a rally at the Hollywood Bowl. More than 20,000 people filled the amphitheater to capacity, and thousands more found seating on surrounding hillsides. They had come to hear their lanky idol Charles Lindbergh headline another America First rally. To pass the time the crowd sang popular folk songs, laughing and smiling as the sun moved toward the horizon.

The program started at 8:00 P.M. with a series of speakers, including silent film star Lillian Gish and Senator D. Worth Clark (D-Idaho). When Lindbergh was introduced, the enormous crowd leapt to its feet, screaming, shouting, and waving American flags. As Lindbergh stood before a podium dense with microphones, photographers wrestled for sightlines and flashbulbs fired in rapid succession. Lindbergh seemed uncomfortable as he shuffled the pages of his typewritten speech in his hands. When the crowd finally quieted, he began.

“We who opposed America’s entrance into this war have one great advantage over the interventionists,” Lindbergh said. “We will be successful if we can bring the true facts and issues of the war clearly before the people of our country. We fight with the blade of truth—they use the bludgeon of propaganda.”

Lindbergh recited his now-familiar litany of reasons why America was safe from attack, why trying to defend England was a fool’s errand, and why a negotiated peace with Hitler was the only reasonable solution.

“The alternative to a negotiated peace is either a Hitler victory or a prostrate Europe, and possibly a prostrate America as well,” he said. When he finished the audience gave him an extended standing ovation complete with cheers of “Lindy” and “Our Next President!”

Even as he spoke, German troops and tanks massed along the Western border of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

Only about 19% of its citizens supported American intervention in the war in Europe in the summer of 1941, but the tide was turning. At a Bastille Day rally in Manhattan on July 14, Roosevelt’s Interior Secretary Harold Ickes claimed that, “No one has ever heard Lindbergh utter a word of horror at, or even aversion to, the bloody career that the Nazis are following, not a word of pity for the innocent men, women, and children who have been murdered by the Nazis.”

Lindbergh had received a high German honor, the Service Cross of the German Eagle, from Reichsmarschall Göring in 1938, and Ickes slammed him directly, saying. “I have never heard this ‘Knight of the German Eagle’ denounce Hitler or Naziism, or Mussolini or fascism.”

The aviator demanded an apology from the president. But “Lindbergh has slipped badly,” Ickes noted in his diary. “He still clings to this German decoration… and is damned if he gives it back and damned if he doesn’t.”

But opposition to FDR was still strong in Congress. Isolationists tried to scuttle the Lend-Lease Program, and fought against changes to the Neutrality Act to permit the arming of American merchant ships and freeing U.S. Navy warships to escort convoys after a German submarine fired torpedoes at the USS Kearny, killing 11 sailors. On Navy Day, October 22, President Roosevelt addressed a crowd of military leaders at the Mayflower Hotel, summarizing the attacks of the previous months.

“We have wished to avoid shooting, but the shooting has started,” FDR said. “And history has recorded who fired the first shot.” Describing a secret Nazi map that showed designs on Central and South America, he said, “All of us Americans are faced with the choice between the kind of world we want to live in and the kind of world which Hitler and his hordes would impose on us.” (The “secret” map later proved to be a plant by British Intelligence.) FDR demanded Congress protect merchant ships and the crowd erupted in cheers when he promised, “It can never be doubted that the goods will be delivered by this nation, whose Navy believes in the tradition of ‘Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.’”

On November 12, Lindbergh met with Henry Ford and enlisted the automaker’s support to keep the America First Committee going. Public perceptions of Lindbergh as an antisemite, while attractive to Ford, had plunged the Committee into a financial crisis. But its leaders and supporters kept on, pressuring the press and urging Congress to keep America neutral.

Twenty-five days later later, FDR was in his private study on the second floor of the White House when the phone rang. His caller was Frank Knox. “Mr. President, we just picked up a radio call from Pearl Harbor advising all our stations that an air raid attached was on and that it was no drill,” the Secretary of the Navy said.

After the smoke cleared from the mangled wreckage, President Roosevelt would persuade the world that free people could overcome the terror of mechanized militaries controlled by brutal totalitarian governments.

On December 8, Charles Lindbergh, speaking for the America First Committee, issued a statement of his own: “We have been stepping closer to war for many months. Now, it has come, we must meet it as united Americans, regardless of our attitude in the past toward the policy our government has followed.”

The isolationist movement had been sunk by the Japanese bombs that landed on Pearl Harbor. But ten days later, Lindbergh told an America First party in Greenwich Village that, “There is only one danger in the world. That is the yellow danger. China and Japan are really bound together against the white race.”

Preferring that Germany would have taken over Poland and Russia to form a bloc with the British “against the yellow people and Bolshevism,” Lindbergh blamed the war on "the British and the fools in Washington.”

“Britain is the real cause of all the trouble in the world today,” he claimed.

The world-famous pilot believed himself a patriot, and, with the country now at war, he wanted to serve. But a meeting with army secretary Henry Stimson went badly. At a meeting with senators, FDR bragged, “I will clip that young man's wings.” Lindbergh was hired by Henry Ford and he made a major contribution to the war effort helping manage Ford's Willow Run factory that produced a B-24 Liberator bomber every hour. Late in the war, he flew 50 combat missions in the Pacific.

Understanding why and how FDR was able to confront and conquer the grave challenges that America faced then provide lessons for us today in an America struggling with dangerous factions bent on undermining democracy.

Today’s political environment, where violent militias spout fascist ideology and anti-semitism, is directly descended from the America First Committee that emerged during the lead up to World War II. Neo-Nazi protestors wearing “Camp Auschwitz” T-shirts and shouting “We Will Not Be Replaced” threaten attacks on Jews and deface synagogues in tactics that mimic the brown-shirted Stormtroopers of Hitler’s Germany.

Now, as then, the spread of disinformation to undermine democracy and encourage racist, anti-immigrant, and anti-semitic conspiracy theories poses an imminent threat.

“Certain techniques of propaganda, created and developed in dictator countries, have been imported into this campaign,” FDR said during his run for president in 1940 about the information war he was fighting. “It is the very simple technique of repeating and repeating and repeating falsehoods, with the idea that by constant repetition and reiteration, with no contradiction, the misstatements will finally come to be believed. They are used to create fear by instilling in the minds of our people doubt of each other, doubt of their government, and doubt of the purposes of their democracy.”

Franklin Roosevelt rose to the occasion, providing vision and confidence to a staggered nation. He took the weight of the free world on his paralyzed legs and carried America into the future, away from its isolationist past and into the age of the global superpower.