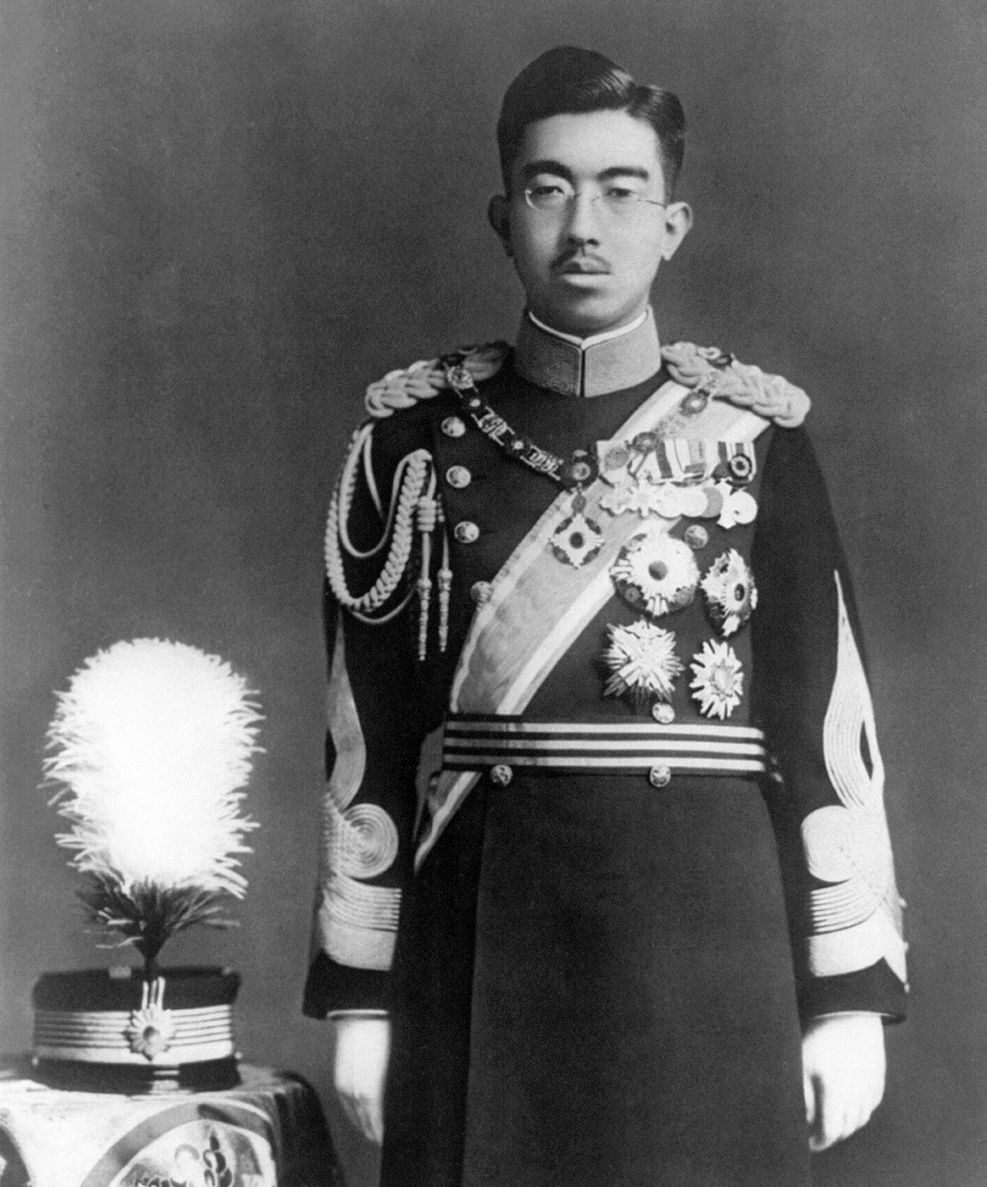

As defeat became inevitable in the summer of 1945, Japan's government and the Allies could not agree on surrender terms, especially regarding the future of Emperor Hirohito and his throne.

-

August 2023

Volume68Issue5

As the Allied armies closed in on the German capital in 1945, the complications for ending the war in Europe paled, in comparison with the difficulty of forcing a Japanese surrender. For the Japanese military, the concept was unthinkable, a state of mind confirmed by the hundreds of thousands of Japanese servicemen who had already been killed, rather than giving up a hopeless contest.

For the Japanese leadership, the whole strategy of the Pacific war had been predicated on the idea that, after initial victories, a compromise would be reached with the Western enemies to avoid having to fight to a surrender. Switzerland was thought of as a possible neutral intermediary; so, too, the Vatican, for which reason a Japanese diplomatic mission was established there early in the war.

The Japanese government watched the situation in Italy closely, when General Pietro Badoglio became prime minister after the fall of Mussolini's fascist regime, and remained in power after the Italian surrender in 1943. If Badoglio could modify unconditional surrender by retaining the government and Victor Emmanuel as king, then a “Badoglio” solution in Japan might ensure the survival of its imperial system.

When a new cabinet was formed in April 1945, after months of military crises, the new prime minister, 78-year-old Kantaro Suzuki, announced on the radio that “the current war has entered a serious stage in which no optimism whatsoever is permissible.” After hearing the broadcast, the former premier, Hideki Tojo, told a journalist, “This is the end. This is our Badoglio government.”

Suzuki was appointed after discussion with the emperor and the Council of Elders because he was among the influential in Japan who favored finding a way to end the war on acceptable terms, but, like Badoglio, he also endorsed the continuation of the war to satisfy the military hardliners in the government who would brook no prospect of surrender. Throughout the months leading to the final capitulation, Japanese politics remained torn between the desire for peace and the imperative to fight if peace proved too costly.

Formal and informal approaches were made to both the United States and the Soviet Union to test whether a negotiated peace might be possible, even though the serial rejection of all Japanese efforts since 1938 to reach a compromise peace agreement with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government ought to have dampened expectations. In April 1945, feelers were put out to see if the same Swiss avenue could be used for Japan. The Japanese naval attaché in Berlin sent his assistant, Fujimura Yoshikazu, to Switzerland, where he succeeded in meeting America's OSS chief there, Allen Dulles, on May 3.

Impressed by the success of the negotiations to bring about surrender in Italy, Fujimura hoped that he could persuade Dulles that a compromise peace could be brokered with Tokyo which allowed the imperial system to survive and permitted Japan to continue to occupy the islands of Micronesia. The talks soon petered out, once the US State Department made it clear that only unconditional surrender was acceptable, while the authorities in Tokyo distrusted any negotiations not under their direct control.

Similar efforts in Stockholm collapsed (as they had done with German approaches earlier in the year). That left the Soviet Union as a possibility, since the two countries were not yet at war.

Japanese views on Soviet intervention in East Asia were mixed. It was generally expected that, at some point, Moscow would abandon the Non-Aggression Pact it had signed in 1941, but whether or when that might result in war was very uncertain. If the Soviet Union would not be willing to broker a peace with the Allies, there was hope that Soviet involvement in Asia might restore the balance against overwhelming American power and perhaps create post-war conditions in which Japan’s future could be preserved more easily than under American domination of East Asia.

As with Hitler and the German leadership, there flourished the hope that conflict between the two wartime allies might leave room for Japan to maneuver (as it eventually did). In July, the Japanese ambassador in Moscow sounded out Soviet willingness to broker a settlement, and found the Soviet side understandably cool. By this stage, a Soviet military build-up on the Manchurian border was evident, although the possible date for a Soviet invasion was speculative.

The idea of using Soviet intervention to moderate the expected draconian American peace was exceedingly risky, given the fact that the Japanese Kempeitai (gestapo) detected rising communist sentiment in Japan and Korea, but it was one of the ways in which the Japanese leadership hoped to avoid a surrender that was rigorously unconditional.

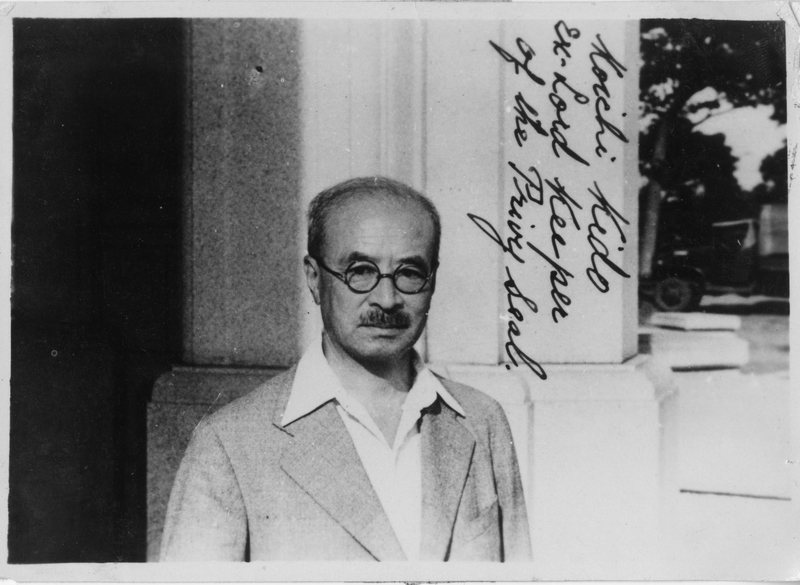

By June, Tokyo faced an impasse. There was no outlet through neutral powers for a negotiated end to the war. The army insisted on maintaining preparations for the final showdown - the American invasion of the home islands, and there was growing evidence, passed on by Hirohito’s confidant, Kido Koichi, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, of popular unrest, even of hostile sentiment toward the emperor himself that was scrawled in graffiti on what was left of the city walls after three months of bombing.

On June 8, Hirohito approved the armed forces’ “Fundamental Policy for the Conduct of the War” because he still thought that some sign of military success was needed before considering an end to the conflict, but, by the 22nd, with the fall of Okinawa, Hirohito finally directed his Supreme War Council to “give immediate and detailed thought to the ways of ending the war ...” because “conditions internal and external to Japan grow tense.”

Over the following weeks, the stalemate continued, but all parties, including the emperor, wanted concessions from the Allies. These varied, from retaining the colonial empire and Japan's interests in China; avoiding occupation; allowing Japan to disarm its forces and punish its own war criminals; and — above all — retaining the imperial system and the kokutai, the national polity. That negotiation might indeed be possible was sustained by regular news from the United States about growing war-weariness and the serious dislocation caused by demobilization and redeployment, which was an evident reality by the summer of 1945.

The Supreme War Council was informed before the meeting on June 8 to confirm military plans that it might be possible, in the light of American domestic difficulties, “to diminish considerably the enemy’s will to continue the war.”

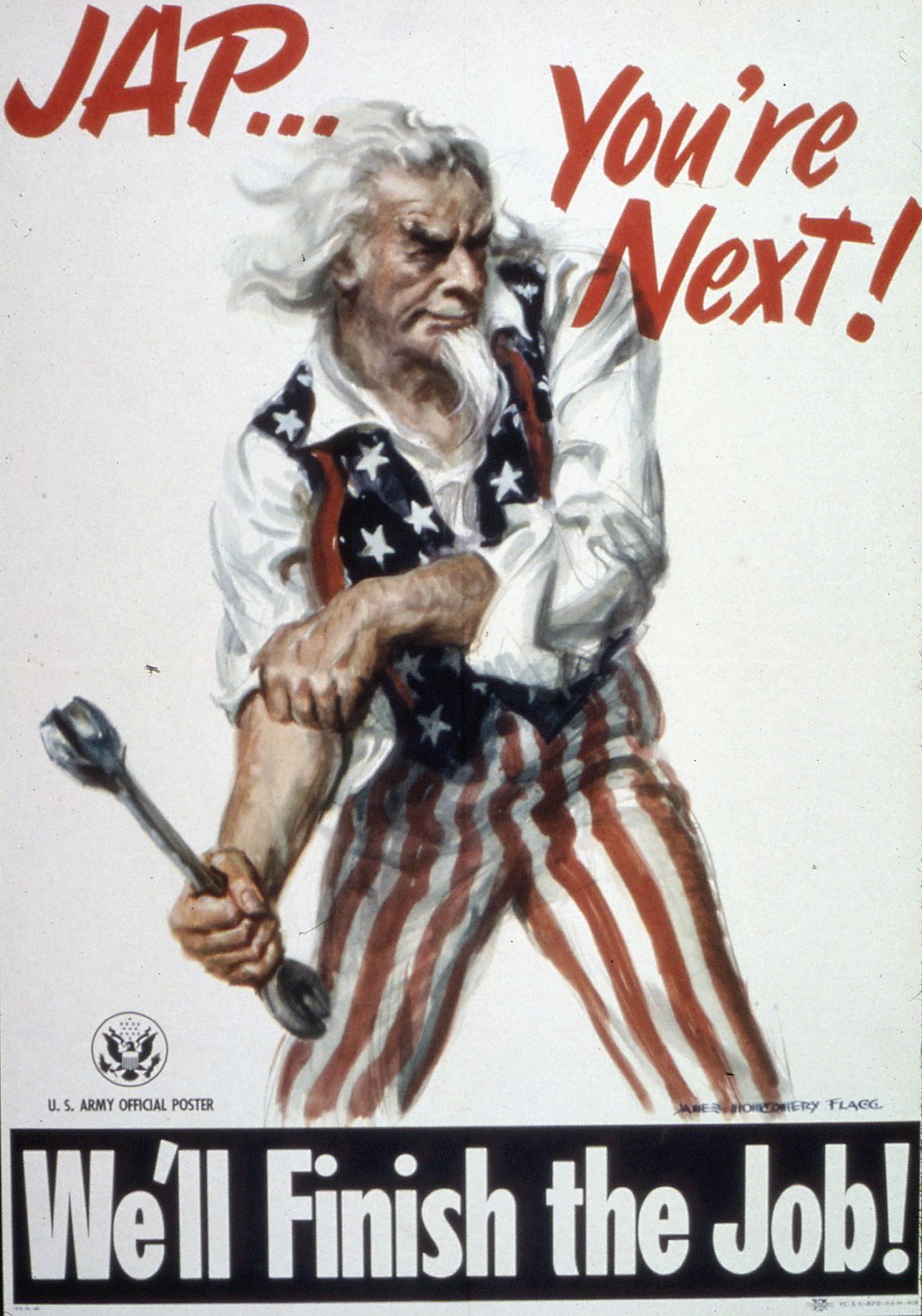

Although Japanese leaders could not know it, there had been much debate in the United States from the spring of 1942 onwards about the status of unconditional surrender in relation to Japan, while there had been none with Germany. State Department officials who favored a “soft peace” worried that, if the Allies insisted on abolishing the imperial institution, it would provide “a permanent incentive for insurgency and revenge.”

By the summer of 1945, American leaders did want to bring the war to a speedy conclusion and did not relish the prospect of an amphibious invasion of the Japanese home islands, once intelligence sources indicated a massive deployment of Japanese troops and equipment on the southern home island of Kyushu, where the first American landing was meant to take place.

Conservatives around the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, feared that the longer the war went on, the greater the risk of Soviet intervention, even Soviet occupation of Japan. A longer war might also mean the prospect of a radical, even communist, movement in Japan, echoing the anxieties in Tokyo. Stimson favored a statement defining unconditional surrender, which would include a “soft peace” that retained the imperial system.

Opponents who favored a “hard peace,” led by the recently appointed Secretary of State, James Byrnes, saw the Stimson proposal as appeasement and refused to give Japan an offer of any conditions. President Truman was against defining a term that seemed self-explanatory, but he was eventually persuaded that a declaration might focus the Japanese desire for peace.

The draft was taken to the inter-Allied conference that convened in Potsdam, Germany on July 17 to iron out the remaining issues between the Allies on the future of Europe, and, here, Stimson’s effort to include a clause protecting the status of the emperor was finally frustrated. Truman, who regarded Hirohito as a war criminal, agreed to replace it with the provision that “the Japanese people will be free to choose their own form of government”, which, as it turned out, left considerable room for interpretation.

The Potsdam Declaration, signed by the United States, Britain and China, was published on July 26 and promised instant destruction if Japan did not surrender unconditionally. It would have been published a week earlier, but it took time to send the document to Chiang Kai-shek’s field headquarters near Chongqing, then decrypt and translate it, and secure his approval.

The Soviet Union was not yet at war with Japan, so it did not sign. Stalin did agree to fulfill his promise made at the Yalta Conference in the Crimea in February that the Soviet Union would go to war with Japan. He told his allies that a campaign was planned for mid-August. Neither side trusted the other’s intentions in Asia, and they had fought, in effect, two separate wars.

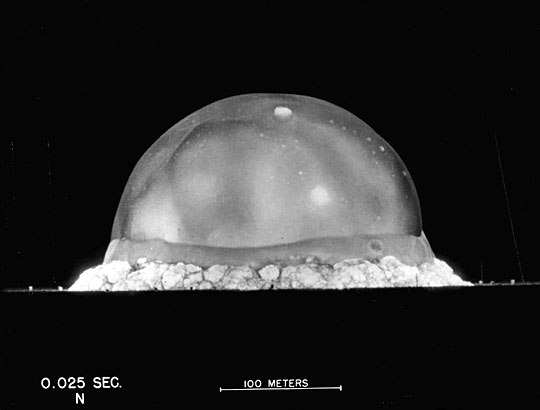

By the time the declaration was published, Harry Truman knew that the threatened “prompt and utter destruction” was about to assume a literal form. On July 16 at Potsdam, he learned that the first test of a nuclear bomb, at the Alamogordo airbase in New Mexico, had succeeded - the culmination of the code-named Manhattan Project, which had begun three years before. The development required an industrial effort on a scale that only the United States could undertake.

The Japanese physicist Nishina Yoshio had embarked on an experimental program to isolate the vital U235 isotope in uranium necessary to make a bomb, but his wooden laboratory burned to the ground in an air raid, and that research project stalled.

In the United States, the Manhattan Project was generously resourced, led by an international group of top physicists, and given high priority. Two bomb models were developed, one based on enriched uranium, the other on plutonium, an artificial element derived from U239 isotopes of uranium. If Germany had not surrendered in May 1945, the first bomb might have been used in Europe. The American Joint Chiefs of Staff were divided over whether it should be used at all, but in the end, the decision was a political, not a military one.

In late July 1945, there were just two bombs ready, one of each kind. Harry Truman, with Churchill’s approval, prepared to use them on two of a selection of Japanese cities that had been preserved from the conventional bombing campaign as possible demonstration targets. "We have discovered," wrote the American president in his diary, "the most terrible bomb in the history of the world."

Whatever scruples might have brought him to hesitate in granting approval were set aside by his belief that the war with Japan could be quickly ended. He added in his diary: "but it can be made the most useful." From his viewpoint, the whole purpose of the years spent developing the bomb was to use it once it was ready.

When it was learned that Prime Minister Suzuki had dismissed the Potsdam Declaration two days later — “the government will ignore it," he claimed — the decision was confirmed to go ahead with the nuclear attacks. Suzuki's rejection was taken as evidence that the Japanese were not serious about seeking peace, though it seems more likely that the declaration was regarded in Tokyo simply as a reiteration of the demand for unconditional surrender, which both sides understood, and which seemed to require no reply. From the list of cities suggested by the Army Air Forces’ commander, Hap Arnold – Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, Nagasaki, and Kyoto (the last of which Stimson had taken off the list because of its preciousness) – the first was chosen.

On August 6, a B-29 bomber called the Enola Gay, flying from Tinian island in the Marianas, dropped the first bomb, insensitively nicknamed Little Boy by the Americans. At 8.16 in the morning, it exploded 1,800 feet above the ground, melting all human life within 1.5 kilometers of the epicenter of the explosion, burning those within 5 kilometers, and then, when the massive blast-wave followed, tearing off the skin and destroying the internal organs of those who had survived the initial flash.

The crew of the bomber watched the huge ball of fire and the mushroom cloud as they headed back to Tinian. “If I live a hundred years,” wrote the co-pilot, Robert Lewis, in his diary, “I’ll never quite get those few minutes out of my mind.”

Three days later, the Japanese Supreme War Council met for a day of debate about how the war should end. The common assumption by Western leaders, endorsed many times since 1945 in various histories of the Japanese surrender, was that the nuclear attacks were the decisive factor that pushed the Japanese to capitulate.

The pattern of cause and effect seems entirely plausible, yet it masks a more complex Japanese reality. In the context of the conventional bombing offensive, the impact on the ground at Hiroshima did not seem very different from the aftermath of a devastating attack with M-69 incendiaries, which had already burned out almost 60 percent of Japan’s urban area and killed over 260,000 civilians.

By the time Hirohito's Supreme War Council met, there was also the Soviet invasion of Manchuria to consider. On August 8, the Soviet foreign minister informed the Japanese ambassador in Moscow that a state of war would exist between the two countries the following day. Prime Minister Suzuki saw this as decisive, for it ended any hope of Soviet mediation and ran the risk of a Soviet invasion of Japan's colony, Korea, or Japan's home islands.

On the morning of August 9, the emperor's council assembled, and a long argument ensued. Half of the council wanted to continue the fight, unless the Allies abandoned plans for occupation, allowed the Japanese to disarm themselves and to punish their own war criminals, and kept the imperial system intact. The other half followed Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori in accepting the Potsdam Declaration, provided the imperial system would be retained.

None of those present favored surrendering unconditionally, even after news arrived that a second bomb, this time the Fat Man plutonium bomb, had been dropped over Nagasaki that morning (rather than the intended target of Kokura, which had been obscured by clouds). The deadlock was only resolved late on the 9th when Hirohito, lobbied by Suzuki and Kido, agreed to call a late-night imperial conference.

The Privy Council president, Hiranuma Kiichiro, told the meeting that the domestic situation was reaching a crisis point: “Continuation of the war will create greater domestic disorder than termination of the war.” For weeks, Hirohito had been warned that popular feeling against the war and his own person was fueled by the endless napalm bombing and a widespread food crisis, and this almost certainly weighed on him as much as did the atomic bomb and the Soviet invasion.

When Suzuki finally asked the emperor to intervene in the early hours of the 10th, Hirohito announced that he sanctioned the decision to accept the Potsdam Declaration if the imperial system was retained. The following day, the Allies were notified formally of the conditional acceptance of their terms.

The American reply was ambiguous because Truman and Byrnes were under strong pressure in Congress to accept the Japanese request so as to prevent further bloodshed. The response to Tokyo confirmed that the emperor and the Japanese government would be subject to the authority of the Allied supreme commander in Japan under the terms of unconditional surrender, but it did not specify that the imperial system would be suspended or abolished. On August 14, a second imperial conference was called, at which Hirohito insisted, against army objections, that the American version be accepted. All the council members were now bound by his decision.

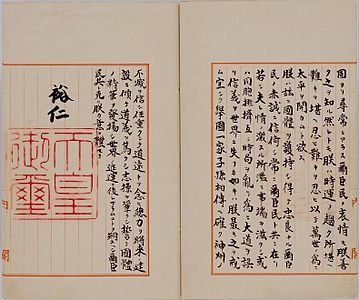

That same day, Hirohito recorded an imperial rescript to be broadcast on the following morning. The Allies were notified through Swiss intermediaries of the emperor’s decision later in the day. The Japanese population was alerted by a radio announcement to expect an important broadcast at noon on the 15th. People gathered during the morning wherever a radio could be set up. The emperor had never before been heard by the public.

When the “Jeweled Voice” finally spoke, the words were difficult to understand, not only because Hirohito spoke in archaic, palatial Japanese, but due to the generally poor radio reception. He spoke, as one listener observed, in “high-pitched, unclear, and faltering words, but the somber tone made it clear that he was informing us of defeat," even if his words were hard to comprehend.

Hirohito did not utter the word "surrender," merely that he would accept the Potsdam Declaration and "bear the unbearable" with his people. Why he took the unprecedented step of intervening to cut through the political arguments of his government and to announce in person the decision to surrender unconditionally will remain open to conjecture, but there seems little reason to favor one explanation over another. He feared the bombing (both nuclear and conventional); he understood that Japan was defeated comprehensively in the field; he did not want a Soviet occupation; and he could see that a major social crisis was erupting.

This monarch was of course a product of his imperial past, which Western historians have been too loath to take at face value. In July, he expressed his private fear that the imperial regalia (the mirror, the sword, and the jewel), handed down over centuries to protect the kokutai and the imperial family, could easily fall into the hands of the invading Allies. In his post-surrender “monologue,” he returned to the theme that Allied seizure of the sacred regalia would mean the end of historic Japan: “I determined that, even if I must sacrifice myself in the process, we had to make peace.”

This was the start of a process of surrender, not the surrender itself. A “Badoglio government” was established as an interim measure on August 15, led by Hirohito’s uncle, Prince Higashikuni. Efforts were made on the 17th to get the Americans to agree to a limited occupation of certain specified areas, but that was rejected. Most of Japan’s far-flung empire was still in Japanese hands, unlike the aftermath of German defeat, and members of the imperial family were sent west and south to order local commanders to surrender their troops.

In Saigon, Singapore, and Nanjing, separate surrender ceremonies took place. Forces in the Pacific surrendered to Admiral Nimitz; forces in Korea south of the 38th parallel, the Philippines, and Japan to Douglas MacArthur. In Singapore, the Japanese surrendered to Louis Mountbatten’s South East Asia Command. On September 9 in Nanjing, the overall Japanese commander in China, General Okamura Yasuji, surrendered his forces in mainland China, Taiwan, and northern Vietnam to Chiang Kai-shek’s representative, General He Yingqin; ignoring the Allied agreements, Mao Zedong’s Communist armies organized the surrender of Japanese forces in northwest China as they fought to seize Japanese weapons and supplies.

The first American occupation forces arrived in Japan on August 28. The Supreme Commander, General MacArthur, arrived two days later. The main surrender document was signed by Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru on board the American battleship Missouri in Tokyo harbor on September 2. Although Stalin had hoped to share the occupation of Japan by sending forces to the northern half of Hokkaido, Truman brusquely rejected that attempt. The Soviet war instead developed its own trajectory as the Red Army pushed on, after the emperor’s broadcast, into the rest of Manchuria and eventually into Korea.

The Japanese army in Manchuria finally signed an armistice on August 19, but the battle for the southern Sakhalin Islands lasted until August 25, while, at the same time, Stalin ordered Soviet forces to occupy the Kuril Islands, including the southern islands assigned at Yalta to the American zone of occupation. These conquests were only completed by September 1, the day before the surrender ceremony. Ceasefires were agreed to independently of the surrenders already taking place farther south.

The unconditional surrenders brought to an end all the wars fought in Europe and East Asia, along with the imperial projects with which they began, but, in each case, ending war proved to be less straightforward than the plain term "unconditional" might have suggested. In Germany and Japan, the surrender prompted a wave of suicides among those who feared retribution, or who were shamed by the comprehensive defeat of the nation-empire, or who could not cope with the extreme emotional and psychological turmoil provoked by the wasted effort to build the new order, or, finally, by those who believed the propaganda about the barbarities that would be meted out by the enemy.

Hitler’s suicide was one of thousands during the final period of fighting and the weeks that followed, including that of Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, who had the misfortune to be present at all three German surrenders, and decided to shoot himself. Eight Nazi party gauleiters committed suicide, plus seven senior SS leaders, fifty-three generals, fourteen air force commanders, and eleven admirals. Josef Terboven, the Reich commissioner in Norway, blew himself up on May 8 with 50 kilograms of dynamite. Among the Nazi party and SS faithful, suicides were common in the months just before and after the surrender. Among the major war criminals prosecuted at Nuremberg, Hans Frank tried to commit suicide, while Robert Ley and Hermann Goring succeeded. Heinrich Himmler avoided trial by swallowing cyanide when he was captured and identified.

A similar reaction followed surrender across Japan and its imperial outposts, where the honorable thing to do following defeat was to commit gyokusai (collective suicide) or seppuku (ritual suicide). In Okinawa, the first Japanese territory to be conquered by American forces, the local population, as well as the soldiers, were ordered to commit mass suicide so as to avoid falling into enemy hands. Some civilians were issued grenades, but others used razors, farm implements, or sticks.

One young Okinawan later recalled stoning his mother and younger siblings to death. Among the Japanese elite, suicide was widespread. Nine senior generals and admirals killed themselves immediately after the surrender, including the war minister, Anami Korechika, and his predecessor, General Sugiyama Hajime, who shot himself a day before his wife, dressed all in white, committed ritual suicide. Hideki Tojo tried to commit seppuku, but failed and stood trial in 1946, after which he was hanged.

For millions of others, on both sides, the surrenders meant relief from the all-embracing demands of total war, but the many arguments between the Allies regarding the surrenders and their aftermath anticipated the coming Cold War, while the unresolved crises generated by imperialism in Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia meant that years of violence and political conflict still lay ahead.

Adapted from Blood and Ruins: The Last Imperial War, 1931-1945 by Richard Overy, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Richard Overy.