The U.S. government managed to hide the magnitude of what happened in Hiroshima until John Hersey’s story appeared in the New Yorker, driving home the truth about America’s new mega-weapon.

-

August 2023

Volume68Issue5

Editor's Note: Lesley M.M. Blume is a journalist and the best-selling author of Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World, from which the following essay is taken.

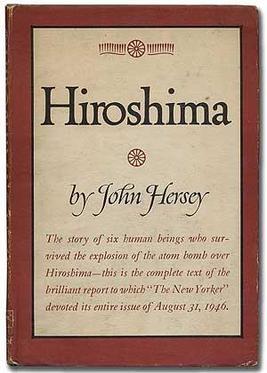

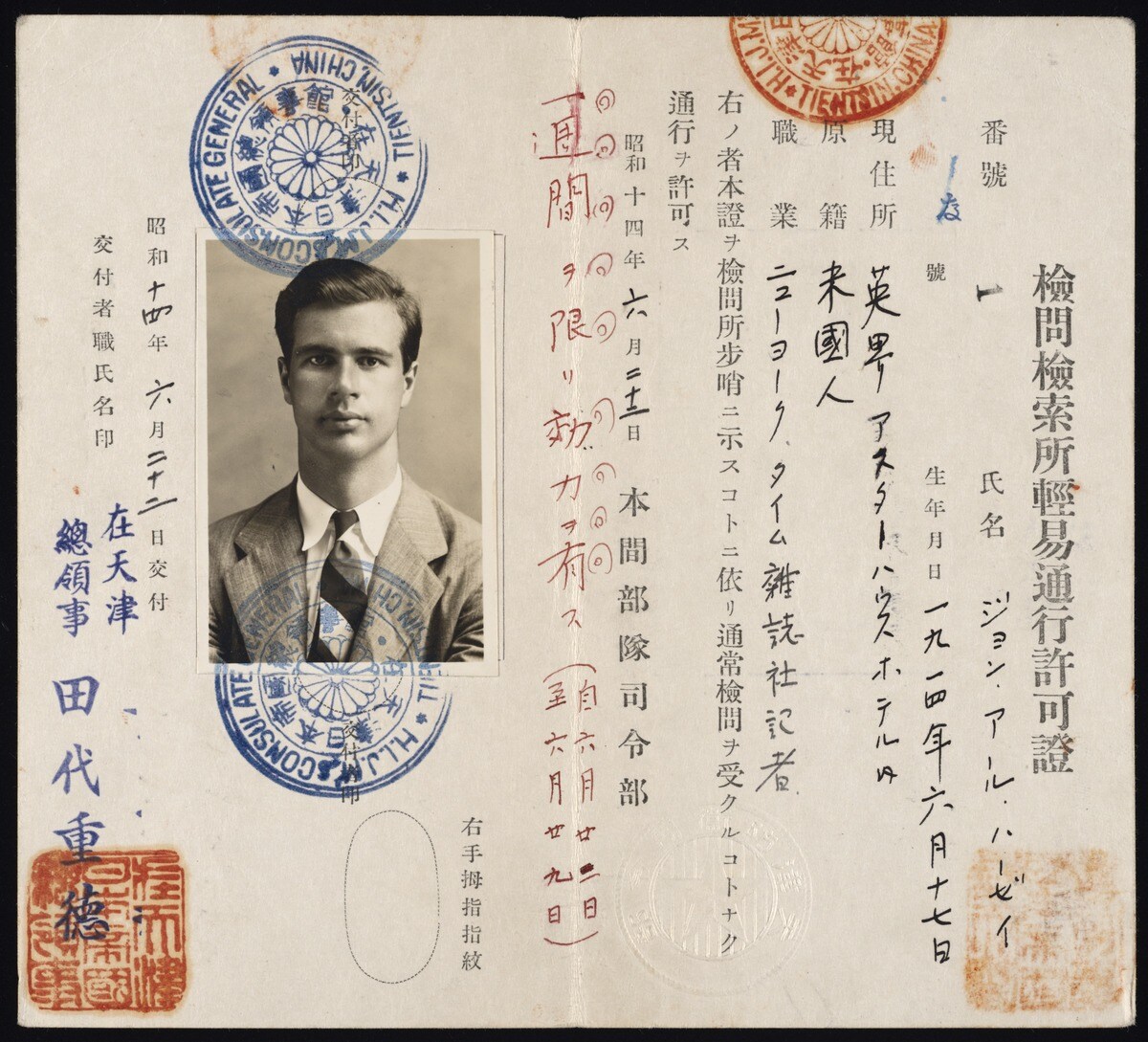

John Hersey later claimed that he had not intended to write an exposé. Yet, in the summer of 1946, he revealed one of the deadliest and most consequential government cover-ups of modern times. The New Yorker magazine devoted its entire August 31, 1946, issue to Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” in which he reported to Americans and the world the full, ghastly realities of atomic warfare in that city, featuring testimony from six of the only humans in history to survive a nuclear attack.

The U.S. government had dropped a nearly 10,000-pound uranium bomb — which had been dubbed “Little Boy” and scribbled with profane messages to the Japanese emperor on Hiroshima a year earlier, at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945. None of the bomb’s creators even knew for certain if the then-experimental weapon would work: Little Boy was the first nuclear weapon to be used in warfare, and Hiroshima’s citizens were chosen as its unfortunate guinea pigs.

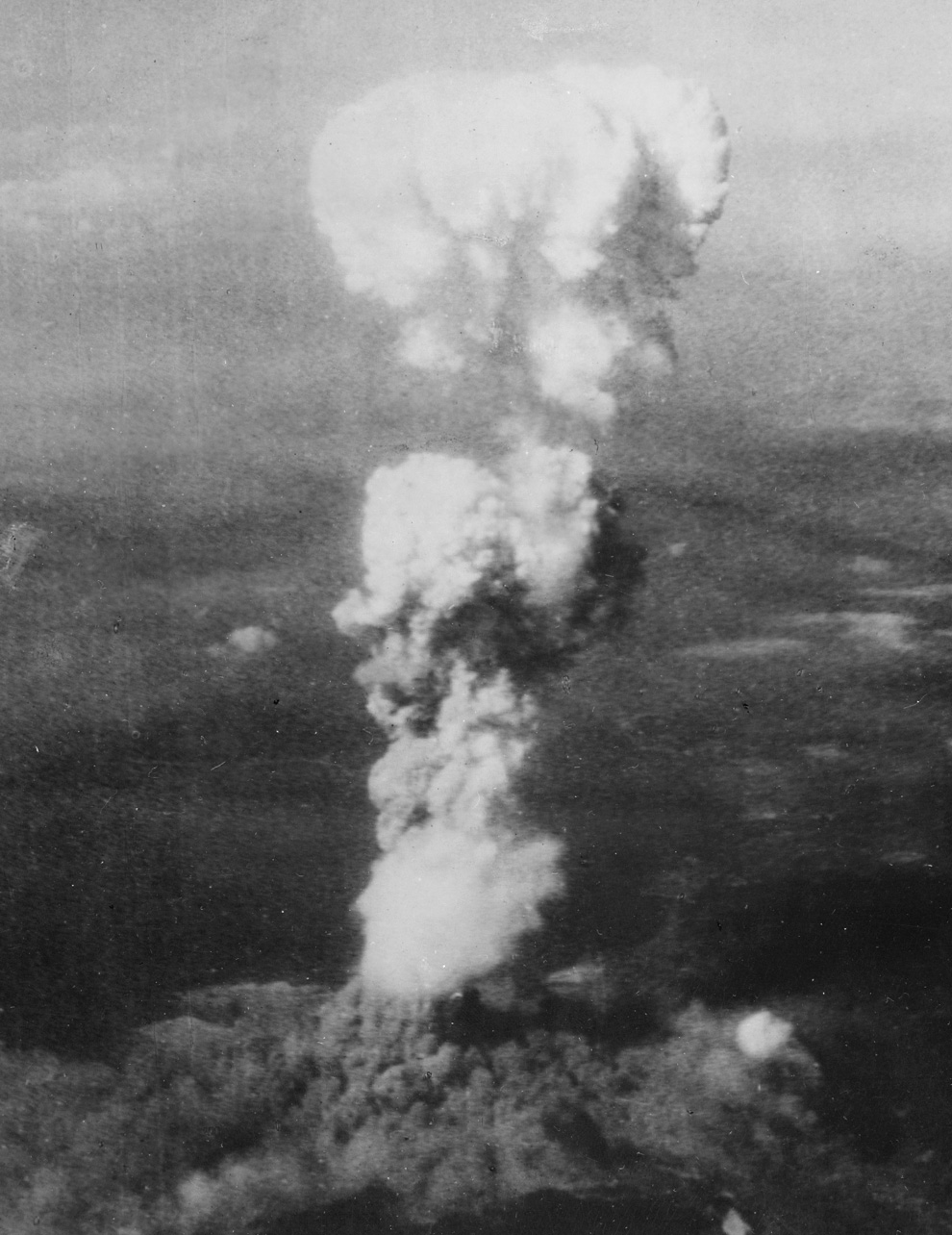

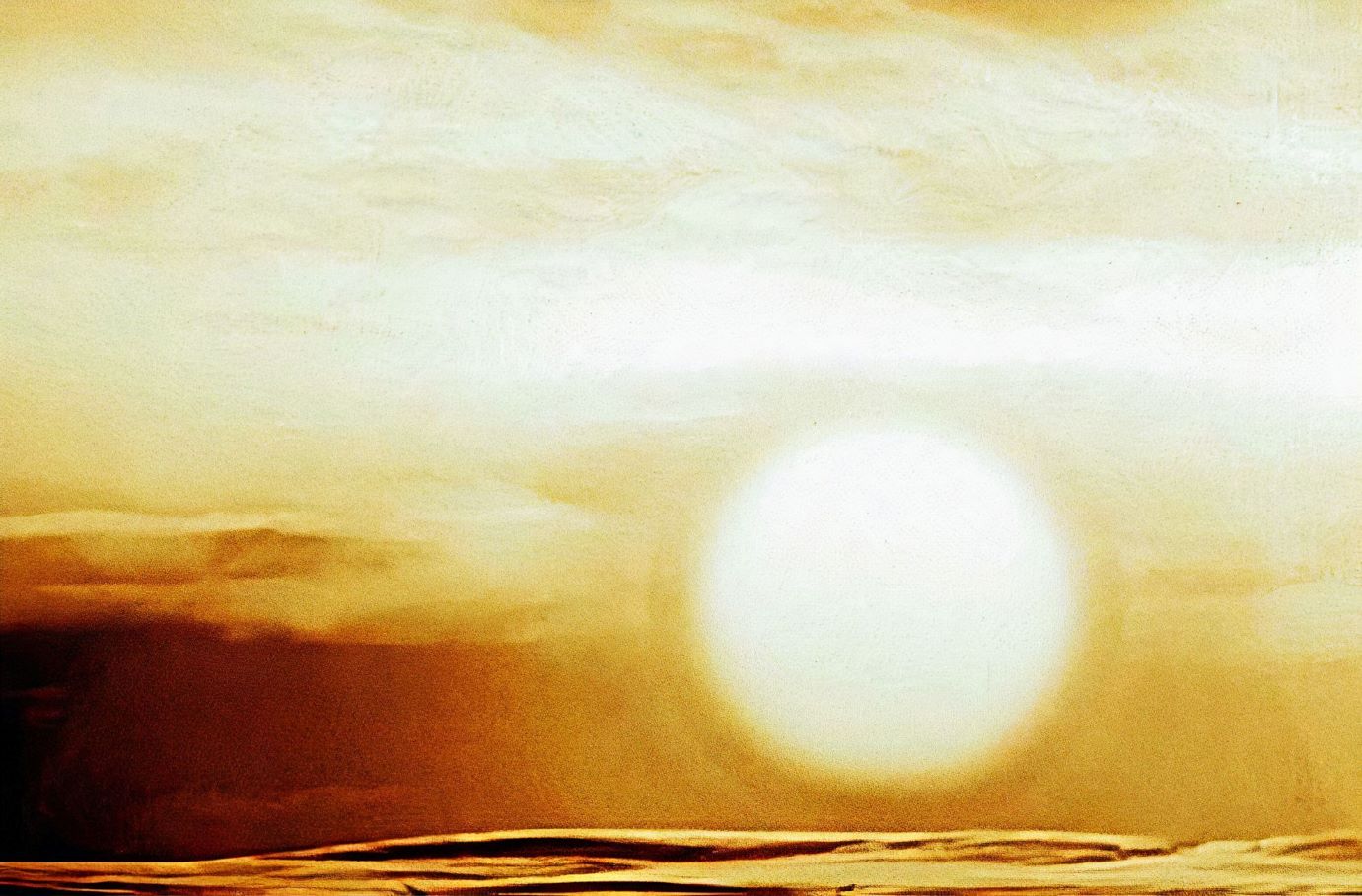

Little Boy exploded about 2000 feet above the city, and tens of thousands of people were burned to death, crushed, or buried alive by collapsing buildings, or bludgeoned by flying debris. Those directly under the bomb’s hypocenter were incinerated, instantaneously erased from existence. Many blast survivors — supposedly the lucky ones — suffered from agonizing radiation poisoning and died by the hundreds in the months that followed.

See “A Straight Path Through Hell” by Joe O’Donnell, the young photographer

who was one of the first to see the devastation

The city of Hiroshima initially estimated that more than 42,000 civilians had died from the bombing. Within a year, that estimate would rise to 100,000. It has since been calculated that as many as 280,000 people may have died by the end of 1945 from effects of the bomb, although the exact number will never be known. In the decades since, human remains have often been uncovered in the city’s ground, and are still found today. “You dig two feet and there are bones,” says Hiroshima Prefecture governor Hidehiko Yuzaki. “We’re living on that. Not only near the epicenter of the blast, but across the city.”

It was a massacre of biblical proportions. Even today — seventy-eight years after the bombing — the name Hiroshima conjures up images of fiery nuclear holocaust, and sends chills down spines around the world.

However, until Hersey’s story appeared in the New Yorker, the U.S. government had astonishingly managed to hide the magnitude of what happened in Hiroshima immediately after the bombing, and successfully covered up the bomb’s long-term, deadly radiological effects. U.S. officials in Washington, D.C. and occupation officials in Japan suppressed, contained, and spun reports from the ground in Hiroshima and Nagasaki — which had been attacked by the United States with the plutonium bomb “Fat Man” on August 9, 1945 — until the story all but disappeared from the headlines and the public’s consciousness.

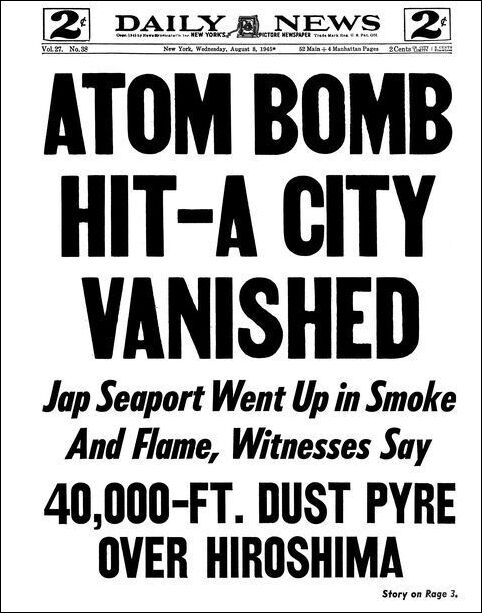

At first, the government appeared to be forthright about its new weapon. When President Harry S. Truman announced to the world that an atomic bomb had just been dropped on Hiroshima, he pledged that, if the Japanese did not surrender, they could “expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.” Little Boy had packed an explosive payload equivalent to more than 20,000 tons of TNT, the president revealed, and was, by far, the largest bomb ever used in the history of warfare.

Reporters and editors given the text of this presidential announcement in advance received the news with disbelief. Young Walter Cronkite — then a United Press reporter based in Europe — upon receiving a bulletin from Paris about the bomb, thought that “clearly... those French operators had made a mistake,” he recalled later. “So, I changed the figure to 20 tons.” Soon, as updates to the story came in, “my mistake became abundantly clear.”

Also, it seemed at first that the press was adequately reporting on the fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As the implications of the world’s entrance into the atomic age began to sink in, it became apparent to editors and reporters everywhere that the atomic bomb was not just one of the biggest stories of the war, but among the biggest news stories in history. After millennia of contriving increasingly horrible and efficient killing machines, humans had finally invented the means with which to extinguish their entire civilization. Humankind was “stealing God’s stuff,” as E. B. White wrote in The New Yorker.

Yet it would take many months — and the bravery of one young American reporter and his editors — before the world learned what had actually transpired beneath those roiling mush-room clouds. “What happened at Hiroshima is not yet known,” reported the New York Times on August 7, 1945. “An impenetrable cloud of dust and smoke masked the target area from reconnaissance planes.”

In many respects, the impenetrable cloud didn’t truly lift until John Hersey got into Hiroshima in May 1946 and, weeks later, managed to publish an account of his findings there. Even though the New York Times was the only publication that had a reporter accompany the Nagasaki atomic bombing run, and had maintained a bureau in Tokyo since the Japanese surrender, Times reporter Arthur Gelb stated that “most of us were unaware, at first, of the extent of the devastation caused by the bombs. John Hersey’s excruciatingly detailed account... finally brought home to Americans the magnitude of the event.”

Media coverage of the bombings had been initially widespread and intensive, but details of the aftermath were actually scarce from the beginning, thanks to U.S. government and military efforts to control information about their handiwork in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The United States — which had just won a painfully earned moral and military victory over the Axis powers — was not eager to “get the reputation for outdoing Hitler in atrocities,” as the country’s Secretary of War Henry Stimson put it. Right away, officials in Washington, D.C., and newly arrived occupation forces in Japan went into overdrive to contain the story of the human cost of their new weapon.

The Japanese media was forbidden by occupation authorities to write or air stories about Hiroshima or Nagasaki, lest they “disturb public tranquility.” As foreign reporters began to get into the country, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were immediately put off-limits to them. The few journalists attempting to report on the atomic cities in the weeks immediately following the bombings were threatened with expulsion from Japan, harassed by U.S. officials, and accused of spreading Japanese propaganda supposedly dispensed by a defeated enemy attempting to cultivate international sympathy after years of aggression and their own horrifying atrocities.

On the home front, U.S. government officials corralled the population into thinking of the atom bomb as a conventional superbomb, painting it in terms of TNT and denying its radioactive aftermath: “It was just the same as getting a bigger gun than the other fellow had to win a war, and that’s what it was used for,” said President Truman. “Nothing else but an artillery weapon.”

When it was eventually conceded that bomb-induced radiation poisoning was real, its horrors were downplayed. It could even be a “very pleasant way to die,” stated Lieutenant General Leslie R. Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, which had created the bombs in just three years.

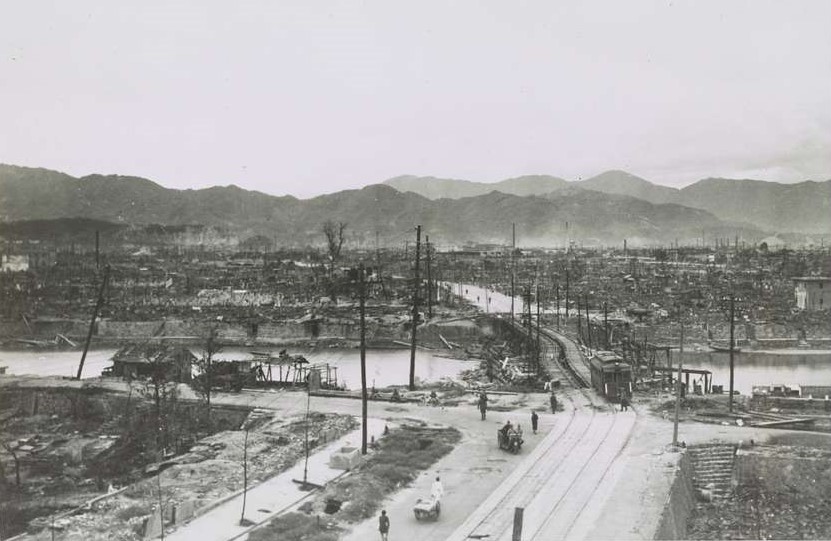

The American public was allowed to see images of the mushroom clouds and hear triumphant eyewitness descriptions from the American bombers themselves, but reports containing survivors' accounts from below the clouds were virtually nonexistent. Images of Hiroshima’s and Nagasaki’s devastated landscapes were also released to newspapers and magazines by U.S. forces. However, while sobering, the post-atomic landscape photographs failed to register deeply enough with readers who had been inundated with images of decimated cities — London, Warsaw, Manila, Dresden, Chungking, and scores of others — on a daily basis for more than half a decade.

Hersey himself acknowledged that post-bomb landscape photos could only get a limited emotional response; ruins, he thought, could be “spectacular; but... impersonal, as rubble so often is.” What the American public did not see: photos of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki hospitals ringed by the corpses of blast survivors who had staggered there seeking medical help and then died in agony on the front steps. (Most of the doctors and nurses had been killed or wounded, anyway.) Nor did they see images of the crematoria burning the remains of thousands of anonymous victims, or pictures of scorched women and children, their hair falling out in fistfuls.

The published images of Hiroshima’s demolished landscape gravely undersold the reality of atomic aftermath. Usually, a picture is worth a thousand words, but, in this case, it would take Hersey’s 30,000 words to reveal and drive home the truth about America’s new mega-weapon. The Japanese, of course, didn’t need Hersey to educate themselves about the effects of Little Boy and Fat Man, but American readers were shocked when they were, at last, properly introduced to the nuclear bombs that had been detonated in their name.

Hiroshima became—and remains—one of the most important works of journalism ever. Over the past nearly eight decades, Hersey’s book has not, of course, prevented dangerous nuclear arms races; nor have its revelations solved the problems of the atomic age, just as the Washington Post’s Watergate reporting did not solve the problem of government corruption.

But, as the document of record—read over the years by millions around the world—graphically showing what nuclear warfare truly looks like, and what atomic bombs do to humans, Hiroshima has played a major role in preventing nuclear war since the end of World War II. In 1946, Hersey’s story was the first truly effective, internationally-heeded warning about the existential threat that nuclear arms posed to civilization. It has since helped motivate generations of activists and leaders to work to prevent nuclear war, which would likely end the brief human experiment on Earth. We know what atomic apocalypse would look like because John Hersey showed us. Since the release of his articles, which then became a book, no leader or party could threaten nuclear action without an absolute knowledge of the horrific results of such an attack. That is, unless that act was one conducted amidst willful ignorance—or nihilistic brutality.

Casualty statistics can be numbing. While the initial lack of comprehension in the United States regarding Hiroshima’s fate was largely due to the government’s active suppression of information from the ground there, it did not help that much of the population was suffering from atrocity exhaustion by the end of the war. By 1946, Americans had been witnesses—along with the rest of the world—to carnage on an unprecedented scale. World War II remains the deadliest conflict in human history. The National World War II Museum estimates that, worldwide, 15 million combatants died, along with some 45 million civilians—although there may have been as many as 50 million civilian casualties among the Chinese alone. Russia puts its losses at 26.6 million dead; the United States lost more than 407,000 military servicemen and women. Every day during the war, gruesome death-toll statistics were announced in American publications from fronts around the globe. The more zeros attached to a statistic, the more unfathomable it was. Somewhere along the way, the numbers seemed to stop representing the bodies of actual people; the human element became divorced from the tallies.

In his articles and book, Hersey informed his readers that 100,000 had died thus far in that atomic city. Yet, had he presented this number and his other findings in a straightforward news story, his writing likely would not have had such a visceral and enduring impact. As one of Hersey’s journalist contemporaries, Lewis Gannett of the New York Herald Tribune, put it, “When headlines say a hundred thousand people are killed, whether in battle, by earthquake, flood, or atom bomb, the human mind refuses to react to mathematics.” In the immediate aftermath of the bombings, Americans were given varying estimates of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki casualties—all of them grotesquely high, especially when one remembered that a single bomb was responsible for all of that death—but to no avail.

“You swallowed statistics, gasped in awe,” Gannett wrote, “and, turning away to discuss the price of lamb chops, forgot. But if you read what Mr. Hersey writes, you won’t forget.”

For Hersey, driving home the gruesome reality behind those impersonal numbers was essential. Since 1939, he had covered various battlefronts and seen the savagery of which humans of all nationalities are capable once they stop seeing their enemies and captives as fellow human beings. The best chance that we had for survival—especially now that warfare had gone nuclear, Hersey felt—was if people could be made to see the essential humanity in each other again.

This was a tall order. To create a work that would help restore a shared sense of humanity, Hersey would not only have to get behind those dangerously anesthetizing stats, but also tackle the virulent racism that had given rise to wartime genocides and atrocities around the globe. Humanizing the Japanese for an American audience would be especially controversial and difficult.

Hatred and suspicion toward the Japanese ran deep in this country after Pearl Harbor. “American pride had dissolved overnight into American rage and hysteria,” Hersey recalled later. Approximately 117,000 people of Japanese descent had been detained in internment camps in the United States during the war. Hollywood had long been hard at work churning out propaganda and feature films warning of the subhuman yellow peril from the East. News about cruelties inflicted on American prisoners of war during the 1942 Bataan Death March in the Philippines, Japanese atrocities committed against civilians in China, and the savage battles over atolls in the Pacific had horrified Americans and reinforced the idea that all Japanese were bestial and fanatical.

In his speech announcing the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman had spoken for many Americans when he stated that, with the atomic attack, the Japanese “have been repaid many fold” for their own attack on Pearl Harbor four years earlier. The citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had gotten what they deserved; it was as simple as that. One poll conducted in mid-August revealed that 85 percent of those surveyed endorsed the bombs’ use, and in a different poll around that same time, 23 percent of those surveyed regretted that the United States didn’t get a chance to use “many more of the bombs before Japan had a chance to surrender.” John Hersey had seen firsthand in Asia and the Pacific evidence of Japanese barbarity and tenacity in battle. Still, he was determined to make sure Americans could see themselves in the citizens of Hiroshima.

“If our concept of . . . civilization was to mean anything,” he stated, “we had to acknowledge the humanity of even our misled and murderous enemies.”

When he got into Japan, and then into Hiroshima—no small feat in an occupied country closely controlled by General Douglas MacArthur and his forces—Hersey managed to interview dozens of blast survivors. Among them: a struggling Japanese widow with three young children; a young female Japanese clerk; two Japanese medics; a young German priest; and a Japanese pastor. In his story for The New Yorker, Hersey recounted—in minute, painful detail—the day of the bombing from each of these six survivors’ point of view.

“They still wondered why they lived when so many others died,” Hersey wrote. That day and since, each had seen “more death than he ever thought he would see.”

Through their eyes, Hersey also made Americans see more death than they ever thought they would see—and a new, uniquely awful version of death, at that. As people read Hiroshima, they visualized New York or Detroit or Seattle in Hiroshima’s stead, and imagined their own families and friends and children enduring the same hell on Earth. Just as Hersey had managed to access Hiroshima itself against the odds, he had successfully breached the fatigue—and tribal barriers—and broken them down. Almost miraculously, he had managed to trigger empathy.

The simplicity of his approach—premised on portraying six relatable people whose lives were violently upended at the same moment— mirrored the basic power of the tiny, mighty atom itself.

The U.S. government’s attempt to suppress information about Hiroshima had been almost ridiculous, Hersey felt; equally absurd was the government’s bid to retain its initial nuclear monopoly. Sooner or later (and likely sooner, he thought) other countries were bound to figure out the physics, and it was only a matter of time before the truth about Hiroshima and Nagasaki got out. Yet, before he had personally gotten into Japan—ten months after the bombings—the American media had already essentially given up on trying to break the story of Hiroshima in a significant way, essentially giving Hersey an unlikely monopoly on the story.

Hersey’s powerful article was released into a frenetic news landscape, with hundreds of stories and international developments vying for reporters’ and the public’s attention. The American press corps was in relentless pursuit of the next scoop, obsessed with getting the edge on the next big story. Dozens of foreign correspondents had been dispatched by their news organizations to Tokyo since the Japanese surrender a year earlier.

Occupation authorities had indeed largely managed to squelch the few bold early attempts to cover Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and they closely monitored and controlled Japan-based reporters after that point. Yet, as time went on, many of Hersey’s reporter colleagues had started to lose interest in reporting on Hiroshima’s fate, anyway. It started to seem like yesterday’s news, and they directed their attention to other stories. Back home, their editors were quietly asked to submit press reports about nuclear matters to the War Department; failure to do so could compromise national security, they were advised. They largely complied.

The New Yorker’s founder and editor, Harold Ross, had directed his wartime writers to find consequential, hiding-in-plain-sight stories ignored by other reporters. Hersey took note, and when the magazine released his long essay, the story not only had the feel of an exposé, but it appeared to be the scoop of the century. (The story had certainly been treated that way in-house at the magazine: Ross and his managing editor, William Shawn, kept the Hiroshima project strictly under wraps— going to almost absurdly dramatic lengths to keep it secret even from the magazine’s own staffers—until just before the article’s release.) When Hersey’s story came out, the media reaction was frenzied: Hiroshima made front-page news around the world and was covered on more than 500 radio stations in the United States alone—even though Hersey’s feat revealed that every other press outlet had actually missed the huge story that they had seemed to cover so diligently.

The public-relations fallout created by Hiroshima also embarrassed the U.S. government, which scrambled to contain the damage. But once the story was published, the genie could not be put back into the bottle. Now that the cover-up was blown, the reality of nuclear aftermath was a matter of permanent, policy-influencing international record. John Hersey had made it impossible for Americans to avert their eyes and, as physicist Albert Einstein put it, “to escape into easy comforts” again.

That said, the Manhattan Project’s chief, General Leslie Groves—who had played a central early role in distorting and hiding information about Hiroshima and the weapon he’d helped create—did play a surprising role in bringing Hiroshima to the masses. And the U.S. government and military would find their own unlikely and cynical utility in the article once it had been published. While Hersey’s story had indeed embarrassed the United States, some government figures realized that it wasn’t entirely a bad thing that it had showcased, to great effect, the devastating power of the United States’ new weapon—a most unwelcome reminder to America’s rivals, who were still years away from developing their own nuclear weapons.

To that end, the Soviets deeply resented Hiroshima and its author; their hostility became increasingly vehement over time. Actions were taken in Russia to debunk Hersey’s revelations, smear Hersey himself, and downplay the might of America’s new bombs. In retrospect, his classic article reveals much about the U.S. government’s internal conflict over how much to showcase about the atomic bomb and how much to hide about it at all costs.

Whatever import Hiroshima took on in various realms, Hersey and his editors at The New Yorker always saw the article as a document of conscience. Also released almost immediately in book form around the world and in many languages, the story—with its continued ability to engulf readers emotionally—has sold millions of copies and long acted as a pillar of deterrence. Years later, Hersey would comment on the role that such eyewitness testimony had played in keeping subsequent generations of leaders from incinerating the planet. It “has not been deterrence, in the sense of fear of specific weapons,” he said, “so much as it’s been memory - the memory of what happened at Hiroshima.”

Most journalistic works have short shelf lives. Yet John Hersey's is dated in only one respect: the story’s hell-wreaking main character, Little Boy, was already considered primitive by the time Hersey wrote his 1946 story just months after the bomb’s detonation. The United States had already begun developing the hydrogen bomb, which would prove many times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan.

Today’s nuclear arsenals include hundreds of bombs vastly more powerful than Little Boy or Fat Man. The most powerful nuclear device—called the Tsar Bomba (a.k.a. Vanya), detonated by the Soviets in 1961—was reportedly 1,570 times more powerful than the yield of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and ten times more powerful than all of the conventional weapons exploded during World War II. It is estimated that the world’s current combined inventory of nuclear arms includes approximately 13,000 warheads. Should war break out today, the prognosis for civilization’s survival is grim; as Einstein said after the Japan bombings: “I do not know how the Third World War will be fought, but I can tell you what they will use in the Fourth—rocks.”

Rampaging climate change and pandemic have been cited as the immediate and greatest threats to human survival, yet nuclear weapons continue to pose another urgent existential menace—and according to nuclear experts, that threat has never been more imminent. The onset of climate change has been violent and frightening, yet its effects are relatively gradual. Nuclear war, on the other hand, could spell instantaneous global destruction, with little or no advance warning. John Hersey had, in the 1980s, worried about “slippage”—a hair-trigger mistake or misinterpretation between two nuclear powers that could lead to an immediate, irreversible nuclear confrontation. If such “slippage” occurred now, leaders could, in a matter of minutes, incite events that would wipe out all life on Earth.

In recent years, long-standing barriers to such nuclear conflagrations have been weakened. Leaders of nuclear-armed nations accelerated production of and modernized their nuclear arsenals. International treaties restricting such escalation were abandoned as channels of communication among leaders of nuclear powers deteriorated. North Korea provocatively tests atomic missiles and weapons, while the Trump administration vacillated between provoking North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, ineptly cultivating him, and looking the other way. Joe Biden has avoided melodrama with Pyongyang, while Mr. Kim continues to develop and test his ballistic arsenal. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a nuclear watchdog group, recently set its Doomsday Clock—which gauges the world’s proximity to the possibility of nuclear war—to “90 seconds to midnight,” with midnight meaning nuclear apocalypse. Before 2020, the clock had never been set that close to doomsday—not even in 1953, “the most dangerous year of the Cold War,” says Dr. William J. Perry, former U.S. Secretary of Defense and chair of the Bulletin’s board of sponsors. “Most people don’t understand that the dangers we are facing today are equivalent to those dark days.”

Experts maintain that climate change is contributing to this dangerous nuclear landscape: civil wars sparked in part by environmental upheaval are a factor in forcing refugee movements in record numbers, exacerbating tensions among nations and prompting populations around the globe to elect militaristic leaders. To make matters even worse, the sort of virulent nationalism and racism that helped set the stage for World War II—and which Hersey had worked so hard to break down —has been surging again throughout the world, with much of it fueled by social media.

Americans are proving far from immune to this trend of dehumanization; many have indicated that they would now be willing to inflict extreme mass casualties on civilians of an enemy state via preemptive nuclear attack. A recent survey of 3,000 Americans revealed that a third of those surveyed supported such a strike, even if that meant that a million North Korean civilians would die in the attack. “It’s our best chance of eliminating North Koreans,” stated one person. The purpose of the strike, according to another: “to end North Korea.”

In 1946, Hersey wrote that his protagonists did not yet understand why they had survived the Hiroshima bombing, while tens of thousands of others around them had perished. Part of the reason for writing his account, Hersey felt, was to warn future generations about the cruel impact of a bomb that continues to kill long after it is detonated, and to help ensure that nuclear weapons are never used again. He hoped that his documentation of Hiroshima’s fate would continue to serve as a deterrent. But, if the lesson of Hiroshima was ignored or forgotten, he warned, continued human existence was indeed a “Big If.”

From FALLOUT: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World by Lesley M.M. Blume. Copyright © 2020 by Lesley M.M. Blume. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.