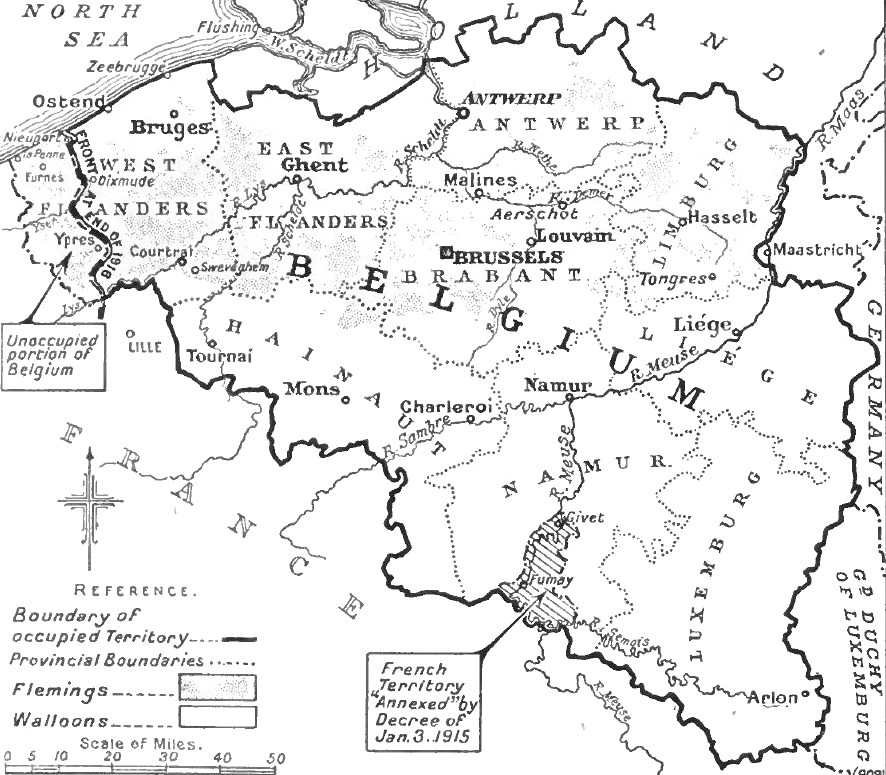

American volunteers distributing food to starving Belgians witnessed the dramatic deportations, when an estimated 120,000 men were taken to factories in Germany.

-

Fall 2018 - World War I Special Issue

Volume63Issue3

Before the start of World War I in August 1914, the Belgian village of Virton, with its hilly streets, massive Catholic church, and remnants of medieval walls, was home to 3500 Walloon, or French-speaking, residents. Located just south of the Ardennes region and less than five miles north of the French border, Virton was the principal town of the small Belgian region known as Gaume, which boasted a warmer microclimate than areas around it. Gently rolling green hills and lush pockets of forest were peaceful dividers between picturesque ancient towns and villages.

When war came, it did not pass lightly over Virton and the surrounding villages. During the invasion, more than 200 men, women, and children were dragged from their homes and executed in one of the worst massacres of the time. Many houses were partially or completely destroyed.

Across Belgium the Germans outlawed all movement outside a person’s neighborhood without a properly authorized Passierschein (safe conduct pass). A constant barrage of affiches commanded Belgians in all matters of life. These placards came from either the local German commander or from Belgium’s German governor general, Baron von Bissing.

Any disobedience was met with harsh fines and sometimes imprisonment.

Nearly two and a half years of occupation had passed when stories of “slave raids” crept into Virton long before the German affiche was posted. When an official proclamation appeared on the town’s walls in late 1916, people read the notice of their turn in the upcoming deportation of Belgian men more with horrified resignation than surprise. It ordered all men between 18 and 55 from the town and the surrounding villages to appear the next day at Virton’s Saint Joseph’s College. The men were to be there at 7:00 a.m. with blankets and three days’ rations. Nothing was said about what would happen to them or where they would go.

"No one slept throughout the night,” wrote Joe Green, an American civilian who witnessed the event. “The women were busy mending and packing clothes and blankets. The men were settling their affairs. The notaries’ offices were crowded with men making their wills. The priests and the burgomasters [mayors] and the leading citizens moved all night from house to house, giving words of encouragement and advice, and promising to look after the wives and children left behind.”

Green was 29 years old, with thick dark-brown hair and a heavy moustache that reinforced his intense look. An air of seriousness rarely left him, and his temper could be like a firecracker—quick and explosive. He did not suffer fools lightly.

And yet, that evening in Virton as he walked among the people he was sworn to help feed, he had to contain his anger and sense of injustice—he was the provincial chief delegate of the American-led Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) and had sworn on his honor as a gentleman to remain neutral when serving in German-occupied Belgium.

The next day dawned heavy, with low-lying pewter clouds and snow that changed back and forth to rain as it fell quietly. The sense of dread and foreboding was heightened by a reminder of the fighting to the south as the big guns thundered off in the distance toward Verdun.

Those who did not obey the affiche were taken from their homes by German soldiers wielding rifles with fixed bayonets. Protests, explanations, and pleadings were lost on the German soldiers, who responded with rough handling and rifle butts to motivate the Belgian men. Women and children stood by helplessly as they watched their husbands, fathers, or brothers forced into the street. They joined others—the ones who had heeded the affiche—trudging toward Saint Joseph’s College. Most of them were workmen dressed in traditional Belgian corduroy pants, coarse shirts, and peasant caps. If it had been farther north in Flemish territory, many would have had on sabots (wooden shoes), but this was Walloon country, so heavy work boots were what most wore.

By 7:00 a.m. the streets around the college were clogged with people. Green was watching and tried to remain calm as “the men, each with his sack on his back, were herded like cattle, village by village. The women and children, kept at a distance, stood in compact masses, wailing, moaning, wringing their hands. Order was kept by the Uhlans, especially brought from France for the purpose.”

German uhlans were lance-carrying cavalry who had become infamous from stories of their brutality during the invasion. When it came to crowds, these cavalrymen knew how to control restless, desperate people. They would ride up and down, using their horses to cut wide swaths through the throng, clearing a path, breaking up little knots of people, always keeping them moving so a crowd could not gather in one place. Each uhlan carried a long lance that had a pennant near the end and a steel, razor-sharp tip. He would carry the pike loosely in hand, not resting in the stirrups, and would brandish it at will above the heads of the women and children.

In Virton, the men who were corralled outside Saint Joseph’s College were called in groups by village. As they stepped forward, they were shoved and shouted at by the soldiers and formed into a single line that led through the gate into the courtyard of the college. There the Belgians found a long table and four German officers—the men who would decide their fate.

No time was given for any meaningful review or analysis of the health, employment status, or general fitness of each man. Any objections Green might have made were ignored. “Scarcely any questions were asked. There was no time for questions. The examinations averaged less than ten seconds per man.” Each man showed his identity card, which had his name, age, and profession. He then waited for the last officer to make his pronouncement, a one-word command in German: links, left, or rechts, right.

Left was freedom. Right was forced deportation.

Green watched as “those who passed to the right disappeared, waving a last farewell” as an “agonized shriek went up from some woman in the crowd.” And as more men disappeared, the crowd become more agitated. Women kept trying to break through the barricade of soldiers to “say one last word to a husband or a son.”

The horrifying scene continued to unfold as the young American bore witness. The women were “pushed back roughly into the crowd, often with kicks and blows. In a short time all the women in the front rows of the crowd were being beaten by the soldiers, both with fists and with the butts of guns. This indescribable scene went on for over half an hour, in plain sight of the groups of [Belgian] men, many of whom were weeping unrestrainedly from rage and helplessness. Finally an officer came out of the court[yard] and put an end to the worst of the brutality.”

As the rain and snow continued to fall, the men marked for deportation were herded by German soldiers with fixed bayonets to the train station. Cattle cars were waiting, and the men were shoved in. Each car had a recommended capacity of only eight horses or 40 men, yet the Germans were known to force up to 60 men into one car. The Virton men probably fared no better.

By nightfall the Virton train, packed with its human cargo, was gone. As the train had pulled away from the station, the men had no doubt been singing, like many before them, the Belgian and French national anthems, “La Brabançonne,” and “La Marseillaise.” Any women and children lining the tracks who had been watching carefully might have seen a few small scraps of paper tossed from the moving cattle cars—hastily scribbled notes from deportees wanting to send one last message to loved ones.

In the end, about a third of the men from Virton were taken and, as Green stated, “almost none under the age of 25 . . . escaped.” The nearby village of Ethe was hit the hardest—only 17 “able-bodied men remaining out of a population of 1500. The women and children will be unable to cultivate the fields next spring. In one family in particular, four little girls are left alone. The mother was shot at the beginning of the war. The father and elder brother are now carried off to Germany.

“The Industrial School at Ethe lost 36 out of its 40 remaining students. This in spite of the formal promise of the Germans that none of the students would be taken.”

Green was shocked and horrified and would never forget what he saw that day in Virton. He ended his official account: “The deportations go on. The Province of Liège, Greater Brussels, and many other localities have not yet passed through the ordeal. Belgium waits.”

He was much more forthright when he wrote his parents about the deportations, dropping any pretense of neutrality: “They are carried out with the last degree of brutality. They are utterly unwarranted by the situation in Belgium and they may simply be regarded as the latest and worst manifestations of that systemized German barbarity which must be crushed.”

The genesis of the deportations—and how the Belgians and a small group of Americans that included Joe Green reacted to them—were all part of a much larger story that had its roots in the early stages of the war.

Neutral Americans Become Part of the War

That larger story was of the American-led, non-governmental Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) and its Belgian counterpart, the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation (CN), which joined forces to try and save nearly 10 million Belgian and northern French civilians from starving to death.

Food relief on such a massive scale had never been attempted before—by governments or private citizens—and was considered impossible during times of war.

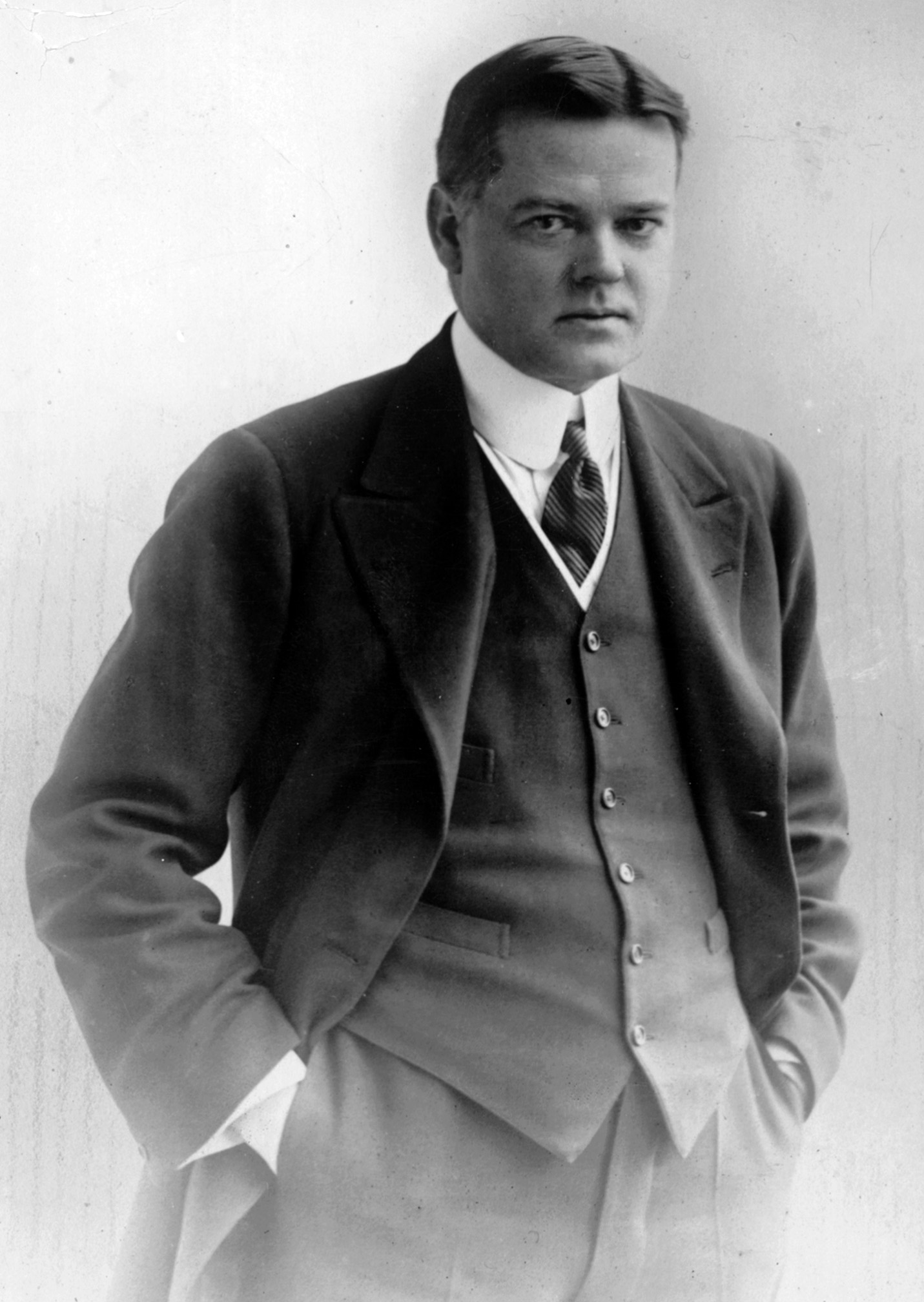

Herbert C. Hoover thought otherwise.

When the war broke out on August 4, 1914, Hoover was a highly successful mining engineer living in London with his wife and two children. He turned 40 on August 10 and was considering public service or politics for the next chapter of his life. Events would quickly offer a unique path.

With the outbreak of war, more than 100,000 American tourists were suddenly trapped in Europe as most transportation, communications, and financial systems were disrupted. Wealthy expats formed charitable committees to help their fellow citizens get home. Hoover assembled a group that became the prominent American tourist relief organization in Britain.

As his charitable work was winding down in October 1914, Hoover heard that more than 7 million civilians in German-occupied Belgium would begin to starve if nothing was done. Belgium, which was slightly smaller than Maryland, was the most densely populated and most industrialized country in Europe and imported nearly 80 percent of all its food before the war. With the German occupation, the country was cut off from the rest of the world, most industries were shuttered, tens of thousands were out of work, and stored food supplies were rapidly being consumed. The Germans steadfastly refused to feed the Belgians. Mass starvation was imminent as autumn turned towards winter.

Responding to the need and ignoring his own mining concerns, Hoover threw himself into the formable task of doing the impossible—feeding an entire nation trapped in the middle of a world war. On Oct. 22, 1914, he and a small band of Americans formed what would become the CRB, with the stated tasks of gaining agreement for the food relief from the belligerents, buying tons of food, shipping it to neutral Rotterdam, loading the food onto hundreds of canal barges for entry into Belgium, then storing it in warehouses.

Once the food was in Belgium, the CRB would turn the food over to the provincial committees of the non-governmental CN for food preparation and distribution to more than 7 million Belgian civilians. By early 1915, the CRB had agreed to also take on more than 2 million northern French civilians who were trapped behind German lines.

Because of America’s status as a neutral country, the food was officially consigned to the U.S. Minister of the Legation in Brussels, Brand Whitlock. One stipulation from the British was that neutral Americans be present in Belgium to guarantee the Germans did not take the food and that the food was fairly and evenly distributed. These men became known as CRB delegates.

But where could Hoover get immediately American men who would drop everything, work for free, and go into the unknown of German occupied Belgium to do a job no one could describe? He could not wait for the recruiting of men who had to sail from America.

In the end, these first responders found him. He was approached by students at Oxford (mostly Rhodes scholars) who were about to take six weeks for winter break. Hoover quickly took them up on their offer to spend their break in Belgium. Many of them stayed much longer than their initial six weeks.

Throughout the war, the relief efforts faced huge logistical challenges, international intrigues, and internal conflicts between the CRB and CN leaders. In an incredible twist of fate, Hoover and the leader of the Belgian CN, Émile Franqui, had been on opposite sides of a court case in China years before and disliked each other. Additionally, the CRB delegates had to deal with the British military who didn’t trust the CRB to keep the food out of German hands, the German authorities who believed many of the delegates were Allied spies, and a faction of Belgians who resented their presence and tried to limit their authority.

All such conflicts paled, however, when the Germans began the deportation of Belgian men in late 1916.

The Belgian Unemployed Lead Ultimately to the Deportations

The German occupation had thrown many Belgians out of work. These unemployed, or chômeurs, were a substantial portion of the population. In pre-war Belgium, the total number of civilians working in commerce and industry was nearly 1.8 million. With the start of the occupation, the first enrollment of classified unemployed across the country totaled 760,000, and when dependents of those unemployed were added on, the total came to nearly 1.4 million people.

Added to these chômeurs were Belgians who could have worked for the Germans but refused. They cited The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 (multilateral treaties regarding the conduct and laws of war) that declared people in occupied territory could not be forced to do work that would help the conqueror’s war efforts. While it’s true that most Belgians employed in essential services such as transportation, water, and power did return to work after the invasion, resentment was building and would soon lead to action by some.

The CRB did its part to aid the unemployed. It ultimately hired thousands of Belgians in ancillary relief work—everything from chauffeurs for the delegates’ cars to stenographers, typists, translators, general office personnel, and even mechanics to keep the motorcars running.

Initially, the chômeurs were not an issue with the Germans because they were included in the total population covered by the CRB’s and the CN’s relief efforts. In fact, one of the major tenets of the CRB, according to Hoover, was that no one could be denied food because of employment status. The concept was that all Belgians must be allowed access to relief—then, and only then, those who could pay would pay, and those who couldn’t pay (such as the unemployed and dependents) would receive charity.

Through 1914, the Germans generally went along with the unemployed being part of general relief. They issued statements assuring the Belgians and the world that Belgian men of military age and the unemployed would not be singled out for forced labor or for the nearly inconceivable idea of deportation.

But time, a stalemated war, and the realities of the military’s need for bodies were strong inducements to change German minds.

In 1915, things began to change. German governor general of Belgium, Baron von Bissing, attempted to prod Belgians back to their jobs or to work for the Germans. The first moves were not to force Belgians to work; they were to entice volunteers. Some skilled workmen were offered wages as a high as £2 per day (equivalent to $200 in U.S. dollars today).

The German offers to work, however, fell mainly on patriotically deaf ears. Most preferred to live either on Belgian half wages or on the monetary assistance of the CN and the food assistance of the CN and CRB. The Belgians saw any work performed for the Germans as war work that was directly against their country, against the Allies, and against the stipulations of The Hague Conventions. Across Belgium and northern France, few accepted the German work offers, as most began what some termed the “strike of folded arms.”

While this labor resistance was tolerated for a while, by the spring of 1915 the Germans were losing what little patience they had had, especially when the unemployed in Belgium and northern France were living off the food relief of the CRB and CN while Germans had to be brought in to do the work.

Even in Germany there were numerous articles that called for the German authorities to put all captive peoples to work—forcibly if necessary—as a way of replacing those who were serving in the German Army.

On one side were the German militarists. Their thinking was obvious—if the Belgians and northern French could be forced to work in jobs currently being done by Germans, then those Germans would be free to join the armed forces.

On the other side was the German civilian government in Berlin. It seemed reluctant to implement forced labor, most probably over a concern that worldwide opinion would be strongly against any such action.

Numerous skirmishes between the Germans and Belgian workers through 1915 and early 1916 escalated the situation.

The Americans were in a tough position regarding the coercion of workers and deportations. The Germans were officially breaking no guarantees that had been made regarding relief when they tried to force the unemployed to work, or even to deport them. But the moral issue still remained that the Germans’ actions were barbaric and inhumane. As Hoover explained, there were “no technical violations of relief guarantees,” but this didn’t mean complaints by the CRB weren’t filed and arguments weren’t made to try and stop the Germans. The points Hoover made were twofold, that the coercion of workers would have “disastrous effects . . . not only on neutral opinion, but on the conduct of relief.”

Hoover knew the CRB could not afford to make a direct, moral challenge, which might lead the Germans to shut down the food relief. Instead, Hoover worked the edges of the issue, trying to convince the Germans that coercion and deportation were not in the true interests of Germany, but never stating they were not legally allowed to do so.

In August 1916, there was a major power shift in Germany that would impact the Belgian situation, The relatively moderate civilian leadership of Theobald Bethmann-Hollweg had been replaced by the more aggressive military leadership of Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff.

In early September 1916, another larger change began when Hindenburg demanded of his own country the full mobilization of Germany, which meant implementing conscription. Many Germans did not like the idea of conscription and there were calls in the German press for complete utilization of manpower in the occupied territories of Belgium and Poland before full conscription should be enacted in Germany.

On Tuesday, October 3, 1916, the German General Headquarters issued a decree announcing mass deportations with no destination given, no work identified, and little or no regard for employment status. The decree stated that the “voluntary or involuntary” unemployed “may be compelled to work even outside the place where they are living.” Anyone who resisted could face up to three years in prison and a fine of 10,000 marks.

This was no sporadic effort in a specific place to get the unemployed to work for the Germans, as had been in most cases before. This was mass deportations of all men on a countrywide scale.

At stake were approximately 1.6 million Belgian men—employed and unemployed—between the ages of 17 and 55. Reportedly, the German General Staff had prepared a deportation plan for all the occupied territories within the German Empire. For Belgium, the plan called for 350,000 to 400,000 men to be deported, which meant almost one in four would be taken.

The CRB was drawn deeper into the issue as the Germans in many cases deported Belgians who were employed as critical support staff for the relief.

The Americans Bear Witness

It was during this highly volatile time in late autumn 1916 that Joe Green watched and reported in restrained anger the brutal taking of men from the small town of Virton, in Luxembourg Province. Fellow CRB delegates were seeing and experiencing the same thing, as they stood helplessly on the frontlines of the deportations. All they could do was file reports and hope the brutal “slave raids,” as many called them, were somehow stopped.

U.S. Legation Minister Brand Whitlock wrote, “The delegates were instructed to be present [at the deportations] and to render any service they could, and Mr. [Hallam] Tuck and Mr. [ John A.] Gade, delegates of the C.R.B. in the province of Hainaut, went over to the commune of St. Ghislain on the morning of October twenty-ninth to witness the selections, to prevent the seizure of the employees of the C.N. and the C.R.B., and to distribute food to those who were deported.”

Whitlock reported that when Gade and Tuck came back from observing the deportation they were “sick with horror and full of rage.”

The two men, however, would have to watch many such events. Gade explained that they had to keep “rushing back and forth to whatever place in the province a deportation was to take place, in order to protect and intercede as far as possible for . . . the Belgian employees and office force of the Relief Commission.”

And to control the Belgians, Gade explained, the scene was nearly always the same. In the city of Mons, there were German soldiers, “endless rows of gray, with glistening bayonets [that] lined the roads and barred all approaches. Here and there a mitrailleuse [machine gun] had been set up. Distracted, desperate women, followed by howling children, ran up and down the fields beyond, pleading—aye, praying on their knees—to be permitted to give their men the bundles of clothing just purchased by the sale of the last household articles. But they might as well have prayed to images of stone.”

Such scenes did not escape the notice of the outside world.

The World Reacts to the “Slave Raids”

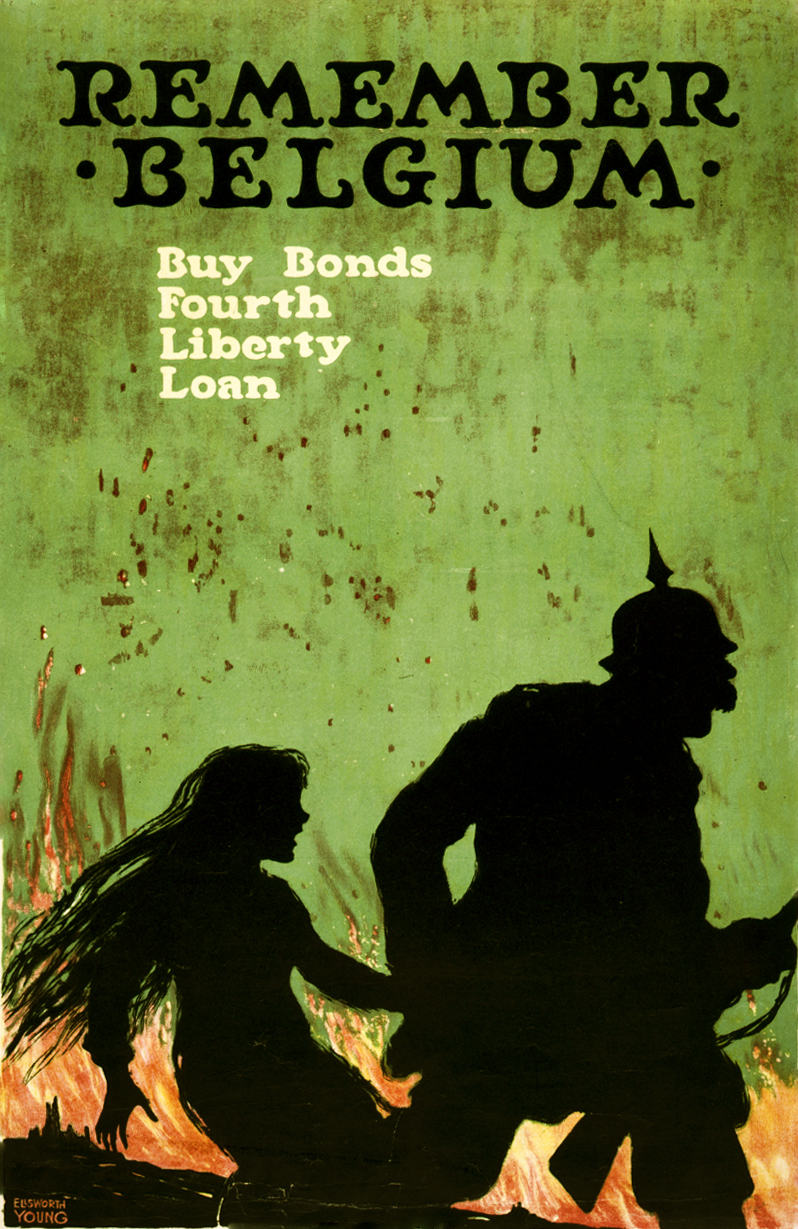

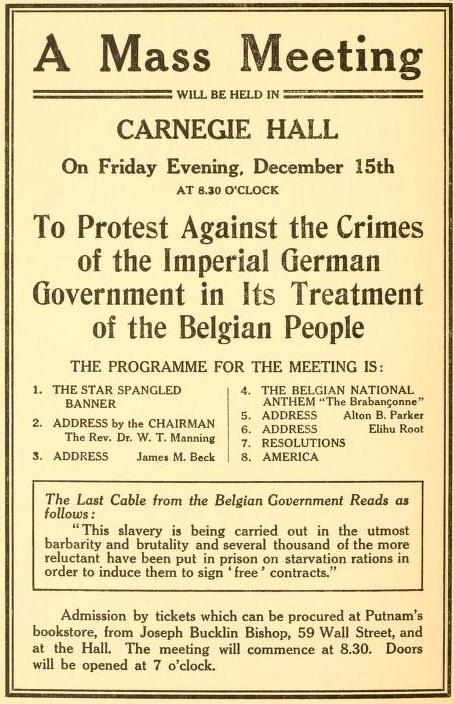

Shortly after the deportations began, the first reports filtered out of the occupied territories to the rest of the world. People around the globe were horrified at the stories of families ripped apart and cattle cars crammed with defiant men yelling, “We will not sign!” or singing the Belgian and French national anthems. To the rest of the world, the deportations quickly became known as “slave raids.” Worldwide condemnation filled nearly every newspaper and magazine, while protest rallies were held.

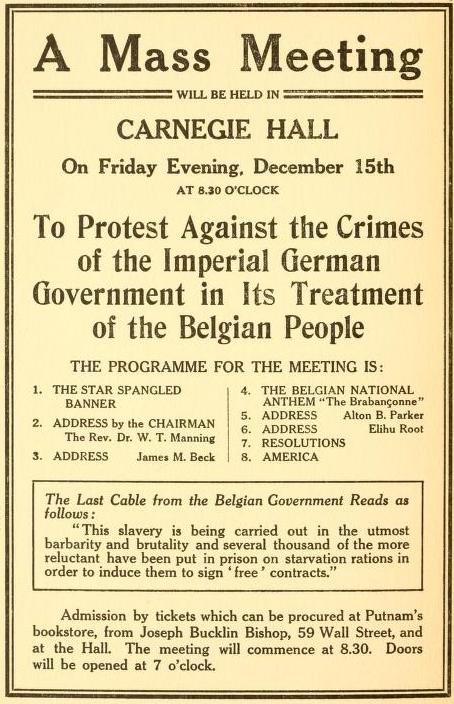

In America, protests were held in multiple cities, including Boston and New York City. The New York Times reported that, on Friday evening, December 15, 1916, Carnegie Hall was “packed to capacity” with more than 3000 people there to protest “against the crimes of the Imperial German Government in its treatment of the Belgian people.” A letter from Teddy Roosevelt was read to loud applause, especially when it came to the statement that “as long as neutrals keep silent, or speak apologetically, or take refuge in the futilities of the professional pacifists, there will be no cessation in these brutalities.”

By the end of the year, multiple countries had lodged official protests with the German government against the inhumanity of the deportations.

Despite the worldwide outcry and official government protests, the German military refused to change its policy. It even turned its back on the objections of its own people. In the German Reichstag, on December 2, 1916, deputies of the minority Independent Socialist Democratic Party stood in the great chamber and protested the deportations. Nothing swayed the German military. Ludendorff stated that the outcry from the rest of the world showed only a “very childish judgment of the war.”

Meanwhile, the Belgians were fighting back as best they could.

A Belgian Moral Voice Rings to the Rafters

The Belgians had not taken the deportations quietly, despite the fact they lived under the harsh German rule. Towns and cities across the country had officially protested with letters to von Bissing that were written and signed by numerous local dignitaries. Countless burgomasters (mayors) and committee members had refused to hand over lists of the unemployed that would have helped the Germans. And some Belgian men, deciding not to chance a cattle car to Germany, had attempted the dangerous clandestine border crossing into Holland so they could join the free Belgians holding the little sliver of free Belgium with King Albert.

Besides the individual Belgian efforts to thwart the Germans in their deportations, there was one mighty voice that could not, and would not, be silenced. It was the moral voice of the country, and it sprang from the tall, willow-reed-thin man of the red cloth—Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier.

Ever since penning a patriotic December 1914 pastoral letter that had circulated around the world, the cardinal had shown no reluctance to reacting strongly over any perceived German injustices against the Belgians. Nearly everything Mercier did either frustrated or angered the German governor general.

Von Bissing used house arrest as a way of keeping Mercier contained, and he tried hard to stop the circulation of any letters or statements from the cardinal, but they always seemed to find their way out to the rest of the country and the world. The solution of full imprisonment or even execution (such as what others suffered for lesser crimes) was unthinkable to the German. He knew his primary job as governor general was maintaining civilian order, and he believed wholeheartedly in the importance of the Catholic Church in helping to keep that order.

Mercier wrote numerous letters to von Bissing and one letter to the world that he had smuggled out of Belgium. His world appeal was widely circulated and helped stimulate unofficial and official condemnation of the deportations. While the pope and countries around the globe did stand up and protest, nothing shook the German military’s resolve to deport Belgian workers.

On Sunday, February 11, 1917, Mercier was visited by the Spanish Minister to Belgium, the Marquis de Villalobar, and the Belgian minister of state, Monsieur Levie. They had a plan to gather the most notable men in Belgium to sign an appeal that would be taken directly to the Kaiser. Mercier agreed immediately not only to sign the document but also to write it.

Mercier wielded as his sword what he knew best, religion. “Your Imperial Majesty prides yourself on your loyalty to your faith. May we not then be allowed to remind you of the simple and yet striking words of the Gospel, ‘Do unto others that which you would have done to yourself ’? . . . We venture to hope that your Majesty will be guided by but one sentiment—that of humanity.”

On Friday, March 9, 1917, word came back to Belgium with the Emperor’s answer. No doubt contrary to what his generals wanted, the Kaiser ordered that all those who had been mistakenly deported as unemployed be returned and that the deportations would be suspended until further orders. On March 14, the imperial degree was officially announced in Brussels publications.

The Kaiser’s decree was a great, but not complete, victory. Only those who had been taken by mistake—meaning men who had jobs when the deportations were supposedly taking just the unemployed—would be returned. Nothing had been said about the vast majority who were unemployed and had been taken forcibly, or of the reported 10,000 to 13,000 who had signed contracts to work for the Germans (whether because they wanted to or because they felt signing would get their families better treatment).

Still, it was a significant victory. After more than a year, and after more than 120,000 had been ripped from their families (no official count was ever made)—the slave raids were over. And some of the men were coming home.

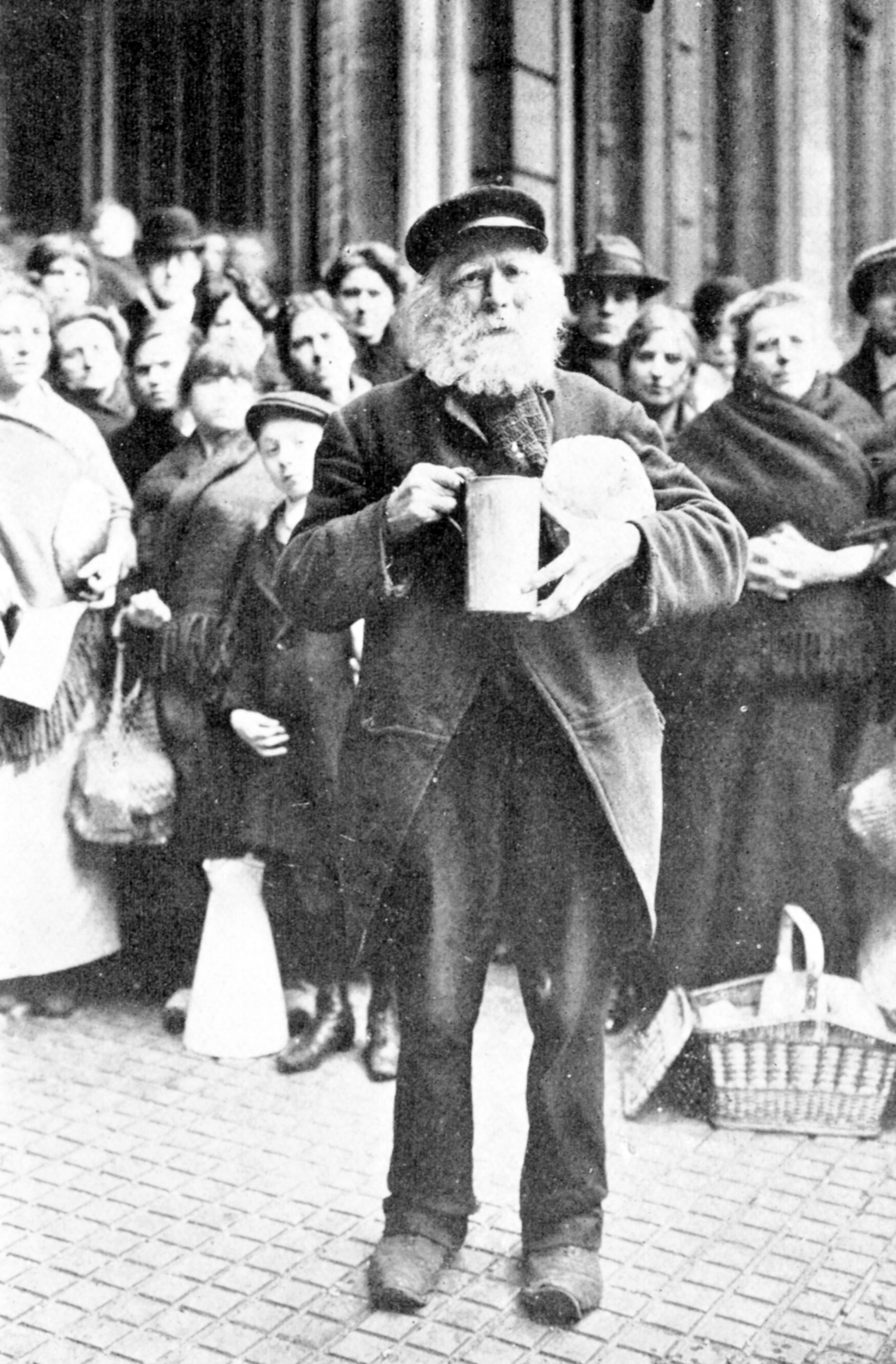

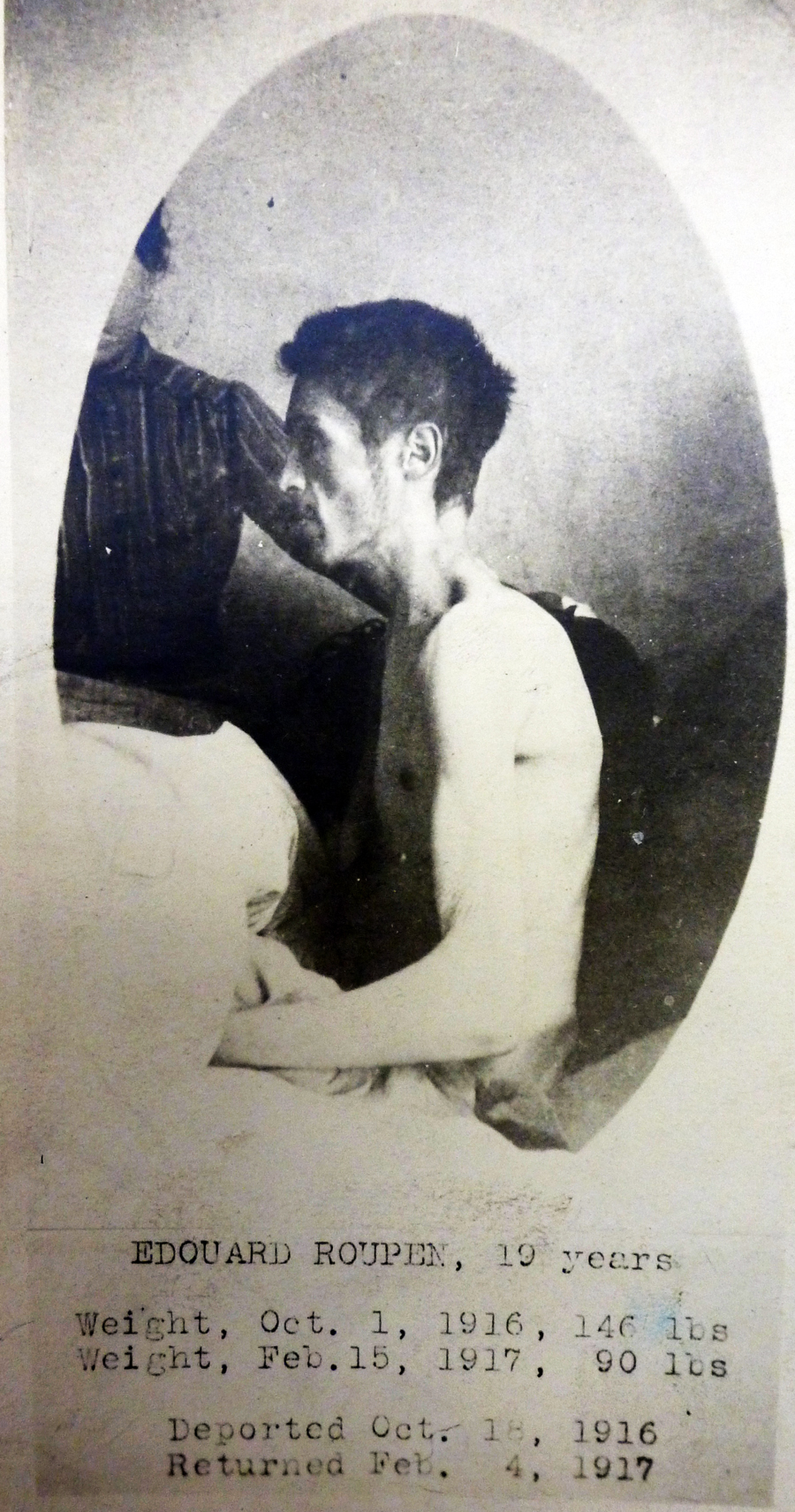

Some Deportees Return—Barely Alive

True to the Kaiser’s word, train cars of Belgian men began to return home. Their condition spoke of harsh treatment and severe deprivation.

One CRB delegate, William Percy, confirmed in March 1917 how physically poor the returning Belgian men were. “I saw trainloads of them arriving in the Antwerp station. They were creatures imagined by El Greco—skeletons, with blue flesh clinging to their bones, too weak to stand alone, too ill to be hungry any longer.” Writing much later, during World War II, Percy commented, “This was only a miniature venture into slavery, a preliminary to the epic conquest and enslavement of whole peoples in 1940, but it seemed hideous and unprecedented to us in 1917.”

He neglected to mention that “left” or “right” became words that defined the brutality of the forced deportations. None who were taken in WWI Belgium, however, could have guessed that those two words would foretell even greater terror only 24 years later as they became forever linked with the horrors of World War II’s Holocaust.

Prentiss Gray gave more details of the condition of the returning deportees when he wrote on Thursday, March 1, 1917, “Today a trainload of returned Deportees pulled into Antwerp from Aix la Chapelle. They had been en route twenty-four hours and during that time fifty-two had died. Every man was carried from the train on a stretcher to the hospital, broken wrecks of humanity for which the Germans could find no more use. Therefore they were being returned to Belgium so as not to use up hospital space or burial crews.”

Gray followed the ambulances to the hospital and spoke to some of the men. “They told stories of their daily ration of a bowl of fish-head soup and a morsel of black bread no larger than your fist: stories of standing in the snow for hours without covering, guarded by a feldwebel [sergeant] who struck them across their freezing fingers when they tried to put their hands in their pockets: stories of standing in icy water till their feet were frost bitten: stories of starvation, of floggings and inhuman treatment.”

Admitting some of the stories might be “overdrawn,” Gray stated strongly, though, that “there were unmistakable signs in their physical condition of suffering beyond human endurance. Evidence there was plenty in frozen feet and hands, great red welts on their emaciated bodies, pneumonia and tuberculosis ran riot among them.”

Many of the deported would not get back to Belgium until the war was over, and others never made it back home.

America Enters The War

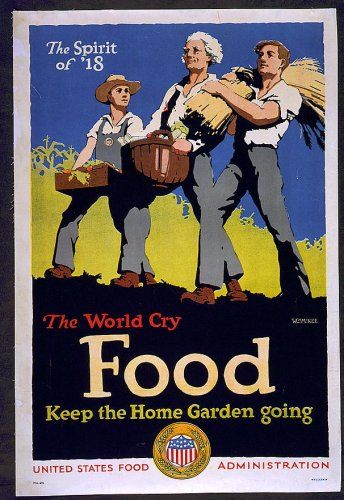

When America did enter the war in April 1917, all American CRB delegates were ordered out of Belgium, but the relief continued with neutral Dutch and Spanish delegates. Both the British and the Germans agreed that Hoover could continue as the head of the CRB and run the relief from London. By the end of the war, the CRB and CN had created the largest food relief program the world had ever seen.

Hoover was soon called back to America by President Wilson to become director of the U.S. Food Administration. He would become known as America’s “food czar” and instituted a voluntary program of food conservation that became known as “Hooverizing.” Homemakers across America embraced the austerity measures to show support for the war and for the man known as the Great Humanitarian.

In the end, the deportations of Belgians were psychologically devastating to the entire civilian population behind the German lines and played a role in shifting American thought and politics away from neutrality.

Author Jeffrey B. Miller has published his extensive research and documented the story of the CRB and CN within the context of German-occupied Belgium in WWI CRUSADERS, which was released on the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I, Veterans Day, November 11, 2018.