Samuel Colt’s life was brief but eventful. He was an imaginative inventor and an ambitious pitchman whose legacy included scandal and success—and firearms that were revolutionary in more ways than one

-

June 1968

Volume19Issue4

The funeral of Samuel Colt, America’s first great munitions maker, was spectacular—certainly the most spectacular ever seen in Hartford, Connecticut. Jt was like the last act of a grand opera, with thrcnodial music played by Colt’s own band of immigrant German craftsmen, supported by a silent chorus of bereaved townsfolk. Crepe bands on their left arms, Colt’s 1,500 workmen filed in pairs past the metallic casket in the parlor of Armsmear, his ducal mansion; then followed his guard—Company A, izth Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers—and the Putnam Phalanx in their brilliant Continental uniforms.

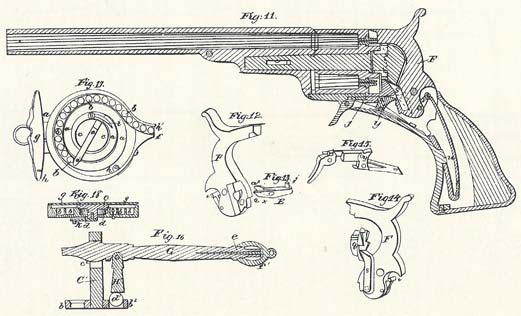

Samuel Colt's design for the Colt Paterson Revolver was patented on August 29th, 1839. Colt enjoyed a domestic monopoly on revolving firearms well into the 1850s.

A half mile away the largest private armory in the world stood quiet—its hundreds of machines idle, the revolvers and riHes on its test range silent. Atop the long dike protecting Colt’s South Meadows development drooped the gray willows that furnished the raw material for his furniture factory. Beneath the dike a few skaters skimmed over the frozen Connecticut River. To the south, the complex of company houses was empty for the moment, as was the village specially built for his Potsdam willow workers.

On Armsmear’s spacious grounds snow covered the deer park, the artificial lake, the statuary, the orchard, the cornfields and meadows, the fabulous greenhouses. At the stable, Mike Tracy, the Irish coachman, stood by Shamrock, the master’s aged, favorite horse, and scanned the long line of sleighs and the thousands of bareheaded onlookers jamming Wethersfield Avenue. After the simple Episcopal service the workers formed two lines, through which the Phalanx solemnly marched—drums muffled, colors draped, and arms reversed. Behind them, eight pallbearers bore the coflin to the private graveyard near the lake.

Thus, on January 14, 1862, Colonel Samuel Colt was laid to rest, at the age of only forty-seven. At the time, lie was America’s best-known and wealthiest inventor, a man who had dreamed an ambitious dream and had made it come true. Sam Colt had raced through a life rich in controversy and calamity and had left behind a public monument and a private mystery. The monument, locally, was the Colt armory; in the world beyond, it was the Colt gun that was to pacify the western and southern frontiers and contribute much to their folklores. The mystery concerned his family, whose entanglements included lawsuits, murder, suicide, and possibly bigamy and bastardy. His had indeed been a full life.

On that January afternoon a kaleidoscope of colorful memories must have crowded the minds of the family and intimates who were present. The foremost mourner was the deceased’s calm and composed young widow, Elizabeth, holding by the hand their three-year-old son Caldwell, the only one of five children to survive infancy. Elizabeth was to become Hartford’s grande dame , and her elaborate memorials would ennoble Colt’s deeds at the same time that they would help conceal the shadows of his past. Her mother, her sister Hetty, and her brothers Richard and John Jarvis, both Colt officials, sat behind her. Richard, then the dependable head of (Jolt’s willow-furniture factory, would in a few years become the armory’s third president. Only the year before, the Colonel had sent John to England to buy surplus guns and equipment. Colt had been extremely fond of both these men, in contrast to his tempestuous relationships with his own three brothers. Near the Jarvises sat Lydia Sigourney, Hartford’s aging, prolific “sweet poetess,” who had been Colt’s friend from his youth and who looked upon Mrs. Colt as “one of the noblest characters, having borne, like true gold, the test of both prosperity and adversity.”

Four of the pallbearers hail played major roles in Colt’s fortunes. They were Thomas H. Seymour, a former governor of Connecticut; Henry C. Deming, mayor of Hartford; Elisha K. Root, mechanical genius and head superintendent of the armory; and Horace Lord, whom Colt had lured away from the gun factory of Eli Whitney, Jr., to become Root’s right-hand man.

And in the background, obscured by the Jarvises and the Colt cousins, was a handsome young man named Samuel Caldwell Colt. In the eyes of the world he was the Colonel’s favorite nephew and the son of the convicted murderer John Colt, but according to local gossip he was really the bastard son of the Colonel himself by a German mistress.

Hartford was stunned by Cult’s early death. True, he had suffered for some time from gout and rheumatic fever; he had indulged fully in the pleasures of life; he had labored from dawn to dusk to the point of exhaustion; then, at Christmas, he had caught a cold and become delirious. Perhaps pneumonia had set in. Whatever the cause of the Colonel’s death, the general reaction was, as one lady put it, that “the main spring is broken, and the works must run down.”

Sam Colt had made his mark in Hartford—and in the world—in less than fourteen years, beginning with his return to his native city to achieve his life’s ambition of having his own gun factory. In the two decades before that he had been a failure at school and in business, but not as an inventor, pitchman, and promoter of himself and his wares.

To many, his brash nature and new-fangled ideas made him seem an outsider—a wild frontiersman rather than a sensible Yankee. Yet Sam’s maternal grandfather, John Cakhvell, had founded the first bank in Hartford, and his own lather was a merchant speculator who had made and lost a fortune in the West Indies trade. Widowed when Sam was only seven—the year the boy took apart his first pistol—Christopher Colt had had to place his children in foster homes. At ten, Sam went to work in his father’s silk mill at Ware, Massachusetts, and later spent less than two years at a private school at Amherst. Sam became interested in chemistry anil electricity, and fashioned a trude underwater mine filled with gunpowder and detonated from shore by an electric current carried through a wire covered with tarred rope. On July 4, 1829, he distributed a handbill proclaiming that “Sam’I Colt will blow a raft sky-high on Ware Pond.” The youngster’s experiment worked too well: the explosion was so great that water doused the villagers’ holiday best. Angrily they ran after the boy, who was shielded by a young machinist whose name was Elisha Root.

Yearning for high adventure, Colt in i 1830 persuaded Iiis lather to let him go to sea. It was arranged for him to work his passage on the brig Corvo , bound for London and Calcutta. “The last time I saw Sam,” a friend wrote to Sam’s father, “he was in tarpaulin [hat], checked shirt, checked trousers, on the fore top-sail yard, loosing the topsail. … He is a manly fellow.”

During this, his sixteenth year, Sam conceived, by observing the action of the ship’s wheel, or possibly the windlass, a practical way for making a mullisbot pistol. Probably from a discarded tackle block, he whittled the first model of a rotating cylinder designed to hold six balls and their charges. The idea was to enable the pawl attached to the hammer of a percussion gun to move as the gun was cocked, thus turning the cylinder mechanically. Ck)It thus became the inventor of what would be ihe definitive part of the first successful revolver. Although he later claimed he had not been aware of the existence of ancient examples of repealing firearms until his second visit to London in 1835, it is likely that he had inspected them in the Tower of London in 1831, when the Corvo docked in the Thames. Moreover, he may have seen the repeating flintlock with a rotating chambered breech invented by Elisha Collier of Boston in 1813 and patented in England in 1818. But since Collier’s gun was cumbersome and the cylinder had to be rotated by hand, Colt cannot be said to have copied its design.

Colt returned to Boston in 1831 with a model of his projected revolver. With money from his father he had two prototypes fabricated, but the first failed to fire and the second exploded. Out of funds, Sam had to scrimp to make his living and to continue the development of his revolver, which he was certain would make him a fortune. At Ware, his exposure to chemistry had introduced him to nitrous oxide, or laughing gas. Sam now set himself up as the “celebrated Dr. Coult of New York, London and Calcutta” and for three years toured Canada and the United States as “a practical chemist,” giving demonstrations for which he charged twenty-five cents admission. Those who inhaled the gas became intoxicated for a few minutes; they would perform ludicrous feats, to the delight of the audience.

In the meantime, Colt had hired John Pearson of Baltimore to make improved models of his revolver, hut he was at his wit’s end trying to keep himself and the constantly grumbling Pearson going. Borrowing a thousand dollars from his father, Colt went to Europe and obtained patents in England and France. In 1836, aided by the U.S. commissioner of patents (a Hartford native named Henry Ellsworth), Colt received U.S. Patent No. 138, on the strength of which he persuaded a conservative cousin, Dudley Seiden, and several other New Yorkers to invest some $200,000 to incorporate the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company of Paterson, New Jersey. Sam got an option to buy a third of the shares (though he was never able to pay for one of them), a yearly salary of $1,000, and a sizable expense account, of which he took full advantage to promote a five-shot revolver in Washington military and congressional circles. (The five-shooter was more practical to produce than a six-shot model based on Colt’s original design.) At the time, the Army Ordinance Department, facing boldly backward, was satisfied with its single-shot breech-loading musket and Hintlock pistol. A West Point competition rejected Colt’s percussion-type arm as too complicated. Meanwhile, Cousin Dudley was growing impatient with Sam’s lavish dinner parties, lack of sales, and mounting debts. At one point he chastised Coll for his liquor bill: “ I have no belief in undertaking to raise the character of your gun by old Madeira.”

The clouds began to break in December of 1837, when Colonel William S. Harney, struggling to subdue the Scminole Indians in the Florida Everglades, ordered one hundred guns, stating, “I am … confident that they are the only things that will finish the infernal war .” Still, (Jolt failed to win over the stubborn head of Ordnance, Colonel George Bomford, until the summer of 1840, when another trial proved his gun’s superiority and forced Bomford to give in slightly; Colt got an order for one hundred carbines at forty dollars apiece. It was a Pyrrhic victory, though, because sales were otherwise too meager to sustain the little company, and in September of 1842 its doors closed for good.

Colt wound up in debt and in controversy with his employers, whom he suspected of fiscal skulduggery. Disgusted with bureaucrats, he determined to be his own boss thereafter. To a member of the family he confided in his half-educated but colorful way:

To be a clerk or an office holder under the pay and patronage of Government, is to stagnate ambition & I hope by hevins I would rather be captain of a canal bote than have the biggest office in the gilt of the Government … however inferior in wealth I may he to the many who surround me I would not exchange lor there treasures the satisfaction 1 have in knowing I have done what lias never before been accomplished by man. … Life is a tiling to be enjoyed … it is the only certainty.

During this period Sam GnIt was also involved in a trying and frustrating family tragedy. His erratic but usually mild older brother, fohn, who was struggling to earn a living by writing a textbook on bookkeeping, had rented a small office in New York City. Then, in September of 1841, he killed his irascible printer, Samuel Adams, after the two had fought over the accuracy of the printer’s bill—their versions differed by less than twenty dollars. John (in self-defense, lie claimed) struck Adams with a hatchet, then stuffed the body into a packing case and had it delivered to a packet bound for New Orleans. A heat wave was his undoing; discovery of the decomposing corpse led to his arrest. Sam went to John’s defense, engaging Cousin Dudley and Robert Emmet as attorneys and scrounging about for funds.

The trial was the newspaper sensation of the year, for it had all the elements of melodrama: a crime of passion, a voluble defendant with friends of influence and means, an aroused populace, a lovely blackeyed blonde, and a bizarre climax.

The girl in the story was Caroline Henshaw, an unschooled young woman who gave birth to a son just before the trial opened in January of 1842. She told the court that she had met John Colt in Philadelphia in 1840, but did not live with him until she came to New York the following January. He taught her to read and write, but eschewed marriage, he said, because of his poverty. Another version had it that Caroline was of German birth, and that it was Sam, not John, who met her first. On his trip to Europe in 1835, the story went, Sam met Caroline in Scotland and brought her back to America as his wife. According to this account, Sam was so preoccupied with his inventions and was away so much that John had, out of pity, made Caroline his common-law wife. Furthermore, because of their social differences, Sam was only too glad to be rid of a partner who might impede his career, which he always placed above personal ties.

In any event, John Colt was convicted of murdering Sam Adams and was sentenced to be hanged on November 18, 1842.

As dawn broke that day, Sam Colt was the first to see John. At about eleven o’clock, Dr. Henry Anthon, rector of St. Mark’s Church, visited the prisoner, who had decided, after conferring with his brother, to make Caroline his lawful wife. John handed the minister five hundred dollars to be used for Caroline’s welfare; he had received the money from Sam—a sizable gift from a man whose factory had failed the month before. A little before noon, Caroline, worn and nervous but smartly dressed in a claret-colored coat and carrying a muff, arrived with Sam. She and John were married by Dr. Anthon. For nearly an hour she remained alone with John in his cell. Then she departed with Sam, and John was left undisturbed.

At five minutes to four the sheriff and Dr. Anthon entered the cell to escort John to the scaffold. But the prisoner lay dead on his bed, a knife with a broken handle buried in his heart. The New York Herald speculated that Colt’s relatives knew of his intention to commit suicide and that they might have smuggled the knife into his cell. The allegation was never proved —or disproved.

Colt secretly arranged for Caroline and her young son to go to Germany. He told his brother James that she “speaks and understands German and can best be cared for in the German countries. … [I have] made all the necessary arrangements and will somehow provide the needful.” At his insistence she changed her name to Miss Julia Leicester, but the boy grew up as Samuel Caldwell Colt.

Caroline and her son remained abroad, supported by Sam. Eventually she became attracted to a young Prussian officer, Baron Friedrich Von Oppen, whose father questioned her background and suspected that money, not love, was Caroline’s motive. But Colt used all his influence to insure a quiet marriage and afterward did everything possible to make the couple and fifteen-year-old Samuel happy.

Apparently the boy did not like book learning any better than Sam himself, so Colt brought him back to America and placed him in a private school. He loaned Caroline $1,000 to enable her husband, who had been disinherited, to enter business. The money was soon dissipated, and Caroline feared debtor’s prison. Sam came to the rescue again, making the Baron his agent in Belgium. But Von Oppen and Caroline drifted apart, and she was lonely without her child. She appealed to Sam to bring her back to America—and there the curtain drops: the beautiful, tormented Caroline Henshaw Colt Von Oppen vanished from Samuel Colt’s life just as he reached the pinnacle of success. She never appeared again, except in a portrait that hung beside one of John Colt at Armsmear, and in the persistent stories (Hartford residents have never let them die) about her true relationship to Samuel Colt.

Even before the demise of the Paterson company in 1842, Colt had been working on two other inventions. In the late thirties he began developing a waterproof cartridge out of tin foil, and he also returned to his experiments with underwater batteries. About the latter he wrote to President John Tyler in 1841:

Discoveries since Fulton’s time combined with an invention original with myself, enable me to effect instant destruction of either Ships or Steamers … on their entering a harbour.

The Navy granted him $6,000 for a test. Using copper wire insulated with layers of waxed and tarred twine, he made four successful demonstrations, one of which blew up a sixty-ton schooner on the Potomac before a host of congressmen. But neither the military nor Congress took to the idea, which John Quincy Adams branded an “unChristian contraption,” and Colt’s Submarine Battery Company never surfaced.

The waterproof cartridges had a better reception, including an endorsement by Winfield Scott, General in Chief of the Army. In 1845 Congress spent one quarter of its $200,000 state militia appropriation on Colt’s ammunition.

Meanwhile, Colt had become acquainted with Professor Samuel F. B. Morse and his electro-magnetic telegraph. The two inventors hit it off from the start. If Colt’s cable could carry an electrical impulse under water to trigger an explosive charge, then it probably could carry telegraphic messages across lakes and rivers. Colt supplied Morse with batteries and wire and won a contract for laying forty miles of wire from Washington to Baltimore. In May of 1846, the same month in which war was declared on Mexico, the New York and Offing Magnetic Telegraph Association was incorporated by Colt and a new set of investors, with the rights to construct a telegraph line from New York City to Long Island and New Jersey. But again the operation was mismanaged, partly because of Colt’s negligence, and at thirty-two he once more found himself as “poor as a churchmouse.” Desperate, he sought—in vain—a captaincy in a new rifle regiment.

Although Colt was not destined to fight in the Mexican War, his guns were. For the five-shot Paterson pistol, having won acceptance against the Seminoles in Florida, had gained further renown in the hands of the Texas Rangers in the early forties. (The sixshot Colt .45, or “Peacemaker,” the gun that supposedly won the West, did not appear until the early 1870’s.) In the summer of 1844, for instance, Captain John C. Hays and fifteen rangers engaged some eighty Comanches in open combat along the Pedernales River and with Colt guns killed or wounded half of them. Altogether, 2,700 Paterson guns, mostly .34 and .36 caliber, were made for the frontiersmen in pocket, belt, and holster sizes. At the close of 1846, without money or machines but still possessed of his patent rights, Colt approached Ranger Captain Samuel H. Walker about buying “improved” arms for his men, who had been mustered into the United States Army. A veteran Indian fighter, Walker needed little encouragement. He wrote Colt:

Without your pistols we would not have had the confidence to have undertaken such daring adventures. … With improvements I think they can be rendered the most perfect weapon in the World for light mounted troops. … The people throughout Texas are anxious to procure your pistols.

That was certainly the case with General Zachary Taylor, commanding troops in Texas in the autumn of 1846. Taylor wanted one thousand Colts within three months, but Colt lacked even a model with which to start manufacturing again. That did not overly distress Colt, because Captain Walker wanted a simpler yet heavier gun—.44 caliber—that would fire six shots. So Colt designed the so-called WTalker gun.

Armed with a $25,000 government order, Sam persuaded Eli Whitney, Jr., the Connecticut contractor for Army muskets, to make the thousand revolvers. They were ready six months later. A pair of guns for Walker, who had hounded Colt for delivery, arrived in Mexico only four days before he was killed in action. To General Sam Houston, who had praised the guns’ superiority, Colt wrote:

I am truly pleased to lern … that your influance unasked for by a poor devil of an inventor has from your own sense of right been employed to du away the prejudice heretofore existing among men who have the power to promote or crush at pleasure all improvements in Fire arms for military purposes.

His appetite whetted, Colt obtained an order for another thousand Walker guns. He borrowed about $5,000 from his banker cousin Elisha Colt and other Hartford businessmen, leased a factory on Pearl Street, and hired scores of hands. Thus, in the summer of 1847, Colt started his own factory, promising to turn out five thousand guns a year. To a friend in Illinois he wrote a letter that reveals much of the basic Colt:

I am working on my own hook and have sole control and management of my business and intend to keep it as long as I live without being subject to the whims of a pack of dam fools and knaves styling themselves a board of directors … my arms sustain a high reputation among men of brains in Mexico and … now is the time to make money out of them.

Alert to the new methods being used in New England’s machine-tool industry, Colt quickly adapted the system of interchangeable parts to the mass production of guns. Though two other Connecticut gunmakers, Simeon North and Whitney, had been the first to standardize parts, Colt perfected the technique to the point where eighty per cent of his gunmaking was done by machine alone.

Vital to his success was his able staff, especially Elisha Root, whom he had first met at Ware and whom he had now lured away from the Collins Axe Company by offering him the unheard-of salary of $5,000 a year. As Colt’s head superintendent, Root designed and constructed the incomparable Colt armory and installed its equipment. During his tenure, Root invented many ingenious belt-driven machines (some of which are still operative) for turning gun stocks, boring and rifling barrels, and making cartridges.

Root’s quiet, firm, perfectionist leadership made Colt’s factory a training center for a succession of gifted mechanics, some of whom went on to apply his modern methods in their own companies. Charles E. Billings and Christopher M. Spencer started a company (now defunct) for making a variety of hand tools; Spencer invented the Spencer rifle, used in the Civil War, as well as the first screw-making machine. Other armory graduates included Francis A. Pratt and Amos Whitney, who together founded a machine-tool company that today is part of Colt Industries.

While Root managed the factory, Colt functioned as president and salesman extraordinary. Far more than his competitors, he appreciated the necessity of creating demand through aggressive promotion. He paid military officers and others to act as his agents in the West and the South and as his lobbyists in Congress, while Colt himself solicited patronage from state governors. Until the approach of the Civil War, however, government sales were scanty compared to the thousands of revolvers shipped to California during the Gold Rush, or to foreign heads of state. From 1849 on, Colt travelled abroad extensively, wangling introductions to government officials and making them gifts of beautifully engraved weapons.

In May of 1851 Colt exhibited five hundred of his machine-made guns and served free brandy at London’s Crystal Palace Exposition. He even read a paper, “Rotating Chambered-Breech Firearms,” to the Institute of Civil Engineers. Two years later he became the first American manufacturer to open a branch abroad, choosing a location on the Thames for supplying the English government with what he termed “the best peesmakers” in the world. So backward did he find England’s mechanical competence, however, that he was forced to send over both journeymen and machines. Colt was ultimately unable to convince the English of the superiority of machine labor, and the London factory was sold in 1857, but not before it and the main plant in Hartford had between them supplied two hundred thousand pistols for use in the Crimean War.

Colt had been successful in obtaining a seven-year extension of his basic American patent and in crushing attempts at infringement. He had become a millionaire in less than a decade. As a loyal Democrat he had finally won his long-sought commission, becoming a colonel and aide-de-camp to his good friend Governor Thomas Seymour.

As demand and production continued to soar, Colt had to seek larger quarters. By the early fifties his dream was to build the largest private armory anywhere. He turned his attention to two hundred acres of lowlands along the Connecticut River below Hartford, which he planned to reclaim by building a dike nearly two miles long against spring flooding. His dike, with French osiers planted on top to prevent erosion, was finished in two years at a cost of $125,000.

Behind the dike soon rose the brownstone armory, with a blue onion-shaped dome topped by a gold ball and a stallion holding a broken spear in its mouth. A giant 25o-horsepower steam engine, its flywheel thirty feet in diameter, drove four hundred various machines by a labyrinth of shafts and belts. By 1857 Colt was turning out 250 finished guns a day.

The buildings were steam heated and gas lighted. Around them he constructed fifty multiple dwellings, in rows, for his workmen and their families; he had streets laid out and a reservoir built. Colt paid good wages but insisted on maximum effort in return. Said one factory notice, evidently written by Colt himself: EVERY MAN EMPLOYED IN OR ABOUT MY ARMOURY WHETHER BY PIECEWIRK OR BY DAYS WIRK IS EXPECTED TO WIRK TEN HOURS DURING THE RUNING OF THE ENGINE, & NO ONE WHO DOSE NOT CHEARFULLY CONCENT TO DU THIS NEED EXPECT TO BE EMPLOYED BY ME .

By “inside contracting” Colt kept his own employment rolls to less than a fourth of the total number who earned their living from the armory. His thirty-one contractors assumed responsibility for their particular operations or departments, hiring their own men and receiving materials and tools from Colt.

The willow trees grew so well on top of the dike that Colt set up a small factory to manufacture willow furniture, which became especially popular in Cuba and South America because of its lightness of weight and its coolness. For his German willow workers he erected a row of two-family brick houses modelled after their homes in Potsdam, and gave them a beer-and-coffee garden as well. For his own pleasure and theirs, he formed them into a brightly uniformed armory band. His final, most forward-looking contribution to his employees’ welfare was Charter Oak Hall, named after the Charter Oak tree that fell in 1856, the year the hall was dedicated.∗ Seating a thousand people, the hall was a meeting place for workers; there they could read, hear lectures or concerts, and hold fairs or dances. ∗The Charter Oak long had been a symbol of Connecticut’s passion for independence. In 1687 the British royal governor was frustrated in his attempt to take away the colony’s charter when a local resident stashed the document in the ancient tree.

Through it all, Sam Colt had remained a rather bibulous bachelor, a. well-fleshed six-footer whose light hazel eyes were beginning to gather more than a few wrinkles about them. But Colonel Colt was now at the peak of his career, and he needed a wife and home; these he acquired with his usual dispatch and pomp. Four years earlier he had met the two daughters of the Reverend William Jarvis of Middletown, downriver from Hartford. He chose as his bride the gracious and gentle Elizabeth, who at thirty was twelve years younger than he. The extravagance of their wedding, on June 5, 1856, rocked Hartford’s staid society. The steamboat Washington Irving , which Colt chartered for the occasion, carried him and his friends to the wedding in Middletown. They boarded in front of the flag-bedecked armory; there was an immense crowd of spectators, and Colt mechanics fired a rifle salute from the cupola. Two days later the Colonel and his bride sailed on the Baltic for a six-month trip to Europe. On their return, Sam began to build his palatial Armsmear on the western edge of his property.

When Armsmear was finished, Colt’s investment in the South Meadows was close to two million dollars—truly a gigantic redevelopment project for that era (and one that he accomplished without borrowing from the bankers he so roundly detested). Yet its importance was largely lost upon the city fathers, and Colt’s father-in-law complained, “Though he pays nearly one tenth of the whole city tax, yet there has been a determination on the part of the Republicans to do nothing for him, or the many hundreds who reside on his property in the South Meadows.”

Although the city finally gave him some tax relief for his improvements, its only physical contribution was three street lamps. And when Sam started a private ferry from the armory across the Connecticut to East Hartford to convey mechanics who could not be accommodated in company housing, the hostile Hartford Courant accused him of trying to “dodge the rights of the Hartford Bridge Company.” So exasperated did the Colonel become over such treatment—which was undoubtedly aggravated by his own brashness—that he made a major change in his will, depriving Connecticut of what would surely have been a great educational institution. He had originally planned to leave a quarter of his estate for “founding a school for the education of practical mechanics and engineers.”

By the end of 1858 the Colonel, his lady, and young Caldwell were comfortably ensconced in Armsmear. The family saw little of Colt, however; as the North and South raced toward cataclysm, Colt was busy making enormous profits by filling the demands of both sides for what he sardonically called “my latest work on ‘Moral Reform.’ ” He seriously considered building a branch armory in either Virginia or Georgia. The Armory’s earnings averaged $237,000 annually until the outbreak of the Civil War, when they soared to over a million. His last shipment of five hundred guns to the South left for Richmond three days after Fort Sumter, packed in boxes marked “hardware.”

Colt regarded slavery not as a moral wrong but as an inefficient economic system. He abhorred abolitionists, denounced John Brown as a traitor, and opposed the election of Lincoln for fear the Union would be destroyed—and a lucrative market thereby lost. Like many other Connecticut manufacturers, he believed that an upset of the status quo would be ruinous to the free trade on which the state’s prosperity depended. Thus, he took a conservative stand on slavery and supported the Democrats because they stressed Union and the Constitution. But at the same time, he shrewdly prepared the armory for a five-year conflict and for the arming of a million men; the prevailing sentiment in Hartford was that a civil war, if it broke out, could not last two months. During a vacation in Cuba in early 1861, Colt wrote Root and Lord, exhorting them to “run the Armory night & day with a double set of hands. … Make hay while the sun shines.”

During the 1860 state elections Colt’s political convictions and their manifestations caused a stir in the press, the Courant leading the attack and the Hartford Times waging a vigorous defense. Colt was known to have used dubious methods in previous campaigns, including having ballot boxes watched to make sure his workers supported Democratic candidates. This time the hostile press accused him of discharging, outright, 66 men, of whom 56 are Republicans. … Many of these were contractors and among his oldest and ablest workmen.” Asserting that their dismissals amounted to “proscription for political opinion,” the discharged Republican workers resolved that “the oppression of free labor by capital, and the attempt to coerce and control the votes of free men, is an outrage upon the rights of the laboring classes.” Colt quickly issued a flat denial:

In no case have I ever hired an operative or discharged one for his political or religious opinions. I hire them for ten hours labor … and for that I pay them punctually every month. …

Yet a few months earlier he had suggested to a politician friend that he pen a resolution urging “us [manufacturers] all to discharge from our imploymen every Black Republican … until the question of slavery is for ever set to rest & the rights of the South secured permanently to them.”

Now Colt’s immense business responsibilities were beginning to wear down his seemingly inexhaustible energies. Bothered by frequent attacks of inflammatory rheumatism and distressed by the death of an infant daughter, he drove himself as if he knew his days were numbered. Smoking Cuban cigars, Colt ruled his domain from a roll-top desk at the armory, often writing his own letters in his left-handed scrawl.

Shortly before he died, he handed the family reins to his brother-in-law, Richard Jarvis, with the admonition that “you and your family must do for me now as I have no one else to call upon. You are the pendulum that must keep the works in motion.” Two of his own brothers were dead, and the other, James, a hot-tempered ne’er-do-well and petty politician, had proved a miserable failure as Colt’s manager in the short-lived London plant and later as an official of the armory. The entire estate, which Mrs. Colt and their son Caldwell controlled, was valued at $15,000,000—an enormous sum in those days—giving Elizabeth an income of $200,000 a year for life. Caldwell grew up to be a good sportsman, an international yachtsman, and a lover of beautiful women; although a vice president, he took little interest in the company, and died a mysterious death in Florida at the age of thirty-six.

Other than Elizabeth and Caldwell, Colt’s major beneficiary was Master Samuel Caldwell Colt, “son of my late brother John Caldwell Colt,” whom even Mrs. Colt regarded favorably. When Sam and his southern bride were married in a large and fashionable wedding at Armsmear in 1863, Elizabeth presented the couple with a house across the street; at her death she left them many of her personal effects. For a short time this handsome, retiring man worked at the armory; he became a director but eventually moved to Farmington and took up gentleman farming. He was always loyal to the memory of Colonel Colt, who his descendants believe was his true father.

Colonel Samuel Colt had adopted as his motto Vincit qui patitur , “He conquers who suffers.” But a better-fitting key to his character is found in a remark he once wrote to his half-brother William: ” ‘It is better to be at the head of a louse than at the tail of a lyonl’ … If I cant be first I wont be second in anything.”

Colt’s ambition was to be first and best, and his means were money and power, both of which he had in full measure. His patriotism, while stronger than that of the average munitions maker, was ever subordinate to his desire to see maintained a commercially favorable status quo between North and South. Colt was not above using bribery and was unashamed of profiteering; he seldom reflected on the moral implications of dealing in weapons of death and destruction.

In fairness, Colt was not alone in his evident amorality: the turbulence of the age had thrown out of focus more than a few of the old values for more than a few of his countrymen. Especially to Connecticut Yankees, who had made their state an arsenal for the nation since colonial days, gunmaking could be no sin. What did bother the diluted Puritan conscience of Colt’s time was that a Hartford aristocrat flouted the tenets of the Congregational Church to which he was born—by a bizarre career, a love of high living, and an over-bearing pride and flamboyance.

It can scarcely be denied that Sam Colt was one of America’s first tycoons, a Yankee peddler who became a dazzling entrepreneur. The success of his many mechanical inventions and refinements was due less to their intrinsic merits—which were considerable—than to his showmanship in telling the world about them. He achieved his goals despite continual adversity for nearly three fourths of his short life. Proud, stubborn, and farsighted, he was a man apart; he was impatient with the old ways, preferring, as he said, to be “paddling his own canoe.”