The Corps is supposed to be tough, and is. This often confounds its enemies and sometimes irritates the nation’s other services

-

February 1959

Volume10Issue2

The United States Marines are a very ancient fighting corps, covered with battle scars and proud of every one of them—so very proud, indeed, that they have developed an extremely high esprit de corps, which has been defined as a state of mind that leads its possessor to think himself vastly superior to members of all other military outfits. They have fought all of their country’s official enemies and a great many more who were national enemies only by temporary and impromptu arrangement, and the fighting has taken them to all parts of the globe, including many areas that they had never been formally invited to enter. They have battled the Seminole Indians; they once put down a riot in the Massachusetts state prison; they broke in the doors of an engine house at Harpers Ferry and squelched John Brown’s abortive uprising of chattel slaves; and on innumerable occasions they have subdued water front disorders arising from the excessive high spirits of regular navy men on shore leave. Also, their excellent red-coated band has played for Presidents of the United States from the earliest days ot the Republic. All in all, they are quite an organization; a fact of which no one is more consistently aware than the Marines themselves.

High officials have at times been of two opinions about the Marines. President Andrew Jackson once tried to abolish the Corps, root and branch, and in the 1890’s a similar move was killed by Congress. Admiral “Hghting Bob” Evans, of Spanish-American War fame, did not think marines were an unmixed blessing on warships, writing bitterly: “The more Marines we have, the lower the intelligence of the crew.” To counter this opinion, Admiral David Glasgow Farragut of the Civil War Navy asserted stoutly that “a ship without Marines is like a garment without buttons,” and the thing that seems to have disturbed Congress the most about recent military reorganization proposals was the fear that they might in some way operate to whittle down the Corps’ size, importance, and independence of action.

The ancestry of the Corps can be traced variously—to a robust wharfside tavern in Philadelphia in 1775, where the first marines were enlisted; to the organization by the British Navy in 1664 of a detachment of seagoing foot soldiers; or, if you want to go a long way back indeed, to the action of the ancient Greeks and Romans in keeping ample details of soldiers on all their war galleys. Wherever you trace it, the idea that a warship can use a few squads of men trained for hand-to-hand fighting, in addition to the complement needed to operate the ship itself, is of long standing, and when the rebellious Colonies undertook to start a navy of their own some months before the proclamation of national independence, the formation of a marine corps was a natural step.

Those first marines were enlisted in the autumn of 1775 at the Tun Tavern, a salty, roast-beef-and-beer establishment on Philadelphia’s Front Street. The tavernkeeper, one Robert Mullan, proved so successful at signing up men that the new Corps commissioned him as a captain, and a recruiting poster of that day dwells enthusiastically on the fine things that would come to a young man who signed up. Each man would get a daily ration of a pound of beef or pork, a pound of bread, and an ample supply of flour, raisins, butter, cheese, oatmeal, molasses, tea, and sugar; not to mention a daily issue of cither a pint of the best wine or half a pint of rum or brandy, as well as a pint of lemonade. A married man could allot half of his pay to his wife, thus providing for her security in his absence, and the man who wrote the poster—Captain Mullan, or some other—emitted a glowing final paragraph:

“The Single Young Man, on his Return to Port, finds himself enabled to cut a Dash on Shore with his GIRL and his GLASS, that might be envied by a Nobleman.”

Enlistments mounted under such stimulus, and when the Navy’s first little squadron of warships (converted merchantmen, hastily given such guns as were available) sailed under Commodore Esek Hopkins in January, 1776, to raid New Providence Island in the Bahamas, more than 200 marines went along. The operation was a typical marines-and-sailors expedition. Hopkins sent a lauding party ashore, and the party seized two British Torts and captured 86 cannon and mortars and a substantial amount of gunpowder that was greatly needed by Washington’s poorly supplied Continental Army. The Marines’ first commandant, Captain Samuel Nicholas of Philadelphia, won promotion to major; Commodore Hopkins got his loot safely back to the mainland. The new country’s first amphibious exploit had been a success.

Since the Continental Navy was very small and vastly outweighed by the British fleet, neither it nor its marines cut a very large figure in the history of the Revolution. Marines did fight at Trenton and at Brandywine, however, and they were most definitely present on the Bonhomme Richard when John Paul Jones captured H.M.S. Serapis in that famous engagement off Flamborough Head. Marines with muskets were stationed in the American ship’s fighting tops and on the poop deck during this engagement, and their fire kept the British ship’s upper deck swept clear—a point of no small importance, since the Bonhomme Richard’s lower-deck battery was put out of action early in the engagement, and this helped to restore the balance. Toward the end of the fight, someone in the American ship’s rigging managed to drop a grenade down an open hatchway in the British ship, the grenade exploded a supply of powder on the gun deck, and the British surrender quickly followed.

The Marines are great on legends, even when these are of modern invention, and a current historian of the Corps avers (tongue in cheek) that when the British captain, early in the fight, called across to ask Jones if he had surrendered, and Jones made his famous reply—“I have not yet begun to fight!”—some disgruntled marine remarked bitterly that there is always some so-and-so who does not get the word.

In any case, the Marines served in the Revolution, acquitting themselves well—and then, alter peace came, went entirely out of existence, along with almost all the rest of the American military establishment, the young Republic having at that moment the innocent notion that it could get along quite well without any armed services at all. This happy frame of mind did not last long. In 1794 Congress began to rebuild the Navy, and the Marines’ resurrection took place on July 11, 1798, when Congress passed the basic act setting up the Marine Corps. It authorized a strength of 33 officers and 848 men, specifying that the Corps should be employed on sea duty, on duty at various posts and garrisons in the United States, and—the all-important clause which permits use of the Marines almost anywhere—”any other duty on shore, as the President, in his discretion, shall direct.”

It was about this time that the Marines’ famous esprit de corps began to develop. This was partly due to sheer force of circumstances. By tradition, detachments of marines on warships served not only as a ready striking force but also as a species of seagoing police to enforce discipline. In the old British Navy, when a line-of-battle ship went into action, armed marines would line up, facing outboard, just behind a row of guns, to keep faint-hearts from deserting their posts, and any ship’s captain relied on his marines to keep order in case of trouble with the crew. As far as the sailors were concerned, therefore, marines were something of a race apart, and of necessity the members of the Corps quickly developed the feeling that they were not just part of a ship’s company but members of a highly special organization that went far beyond their immediate surroundings. They were of the Navy but not in it, and to survive at all they had to build up a sense of cohesion and loyalty to their own group.

The feeling also was consciously fostered by those in authority. Very early in the game, a young marine officer on a warship was insulted, apparently via a punch in the jaw, by a naval officer, and he promptly got a very stiff letter from Major William Ward Burrows, commandant of the new Corps. Burrows wrote sternly that “a Blow ought never to be forgiven, and without you wipe away this Insult offer’d to the Marine Corps, you cannot expect to join our Officers.” Burrows urged the young marine to fight a duel, pointing out that a certain Lieutenant Gale, of the Marines, had been struck by a naval officer during a recent cruise of the U.S.S. Ganges . During the cruise, Lieutenant Gale could get no satisfaction; but as soon as the ship returned to port, he challenged the naval man to a duel, and shot him; and “afterward Politeness was restor’d.”

A distinctive uniform was adopted. During the Revolution, the Marines had worn green coats with white breeches, and when the Corps died, this uniform died also. The new Marines, in 1798, wore surplus army uniforms, including scarlet waistcoat and facings and dark-blue coats and trousers, but by 1804 something more special was devised—blue coats faced with gold and scarlet, white pantaloons, and plumed shakos. Also included was a leftover from the original costume—a stiff leather stock, or neckpiece, worn about the throat, which did not remain part of the uniform forever but which did leave marines with their enduring nickname: “leathernecks.” It was also regulation, in the early 1800’s, for marines to wear long pigtails, which must be powdered liberally with flour each day. What the poor men did about the sticky mess that would inevitably develop when spray or rain turned the flour into a gooey paste is not stated in the regulations.

In addition to the fighting, of which the Corps had a great deal, the early commandants of the Marines had two primary concerns—the development of a stiff discipline, and the business of coping with the professional hostility of army and navy officers. Major Archibald Henderson, who became commandant in 1820 and served in that capacity for 39 years, is generally credited with having done as much as any one man to build the Corps on a solid basis, and he once wrote feelingly to the secretary of the Navy: “Our isolated Corps, with the Army on one side and the Navy on the other (neither friendly) has been struggling ever since its establishment tor its very existence.” As mentioned, President Jackson proposed in 1829 that the Corps be merged either into the infantry or the artillery; Congress refused to hear of it, and when five years later it enlarged the Corps, making it part of the naval establishment but not of the Navy, and giving the commandant the rank of colonel, Jackson readily signed the act.

The tradition of-tough discipline, established in the infancy of the Corps, remains to this day, although disciplinary forms have changed a good deal. There is a record of a private who had been found asleep on sentry go sentenced to walk post for the next two months encumbered by a ball and chain. In 1820, a private court-martialed for desertion was sentenced to wear an iron collar, with a six-pound shot attached, for four months, to forfeit all pay during that period, and then to be drummed ignominiously out of the service. At a slightly later date, a marine who jumped ship could receive three-dozen lashes with the cat-o’-nine-tails, followed by a discharge; and during all of this early period the lash was used freely as a disciplinary means. A minor offender might be deprived of his daily rum allowance for a stated period; marines who got drunk were often punished by being forced to drink one or two quarts of salt water.

It was around 1875 that the famous Marines’ Hymn was written, with its stirring recital of Marine achievements “from the Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli,” and its jeering assertion:

The legend was full-blown by now, and the special Marine spirit of separateness and superiority was well established. There was a certain amount of justification for it, because the Corps by mid-century had soaked up an uncommon amount of fighting in many widely separated places.

There had been the brief, semiofficial naval war with France, and the intermittent wars with the Barbary pirates and other freebooting inhabitants of the African shore of the Mediterranean. Amid this, in 1805, there had been the astonishing Goo-mile march from Egypt to Derne of a heterogeneous force under General William Eaton, an American diplomatic agent who had recruited a highly mixed little army in the Near East to come overland and unseat the Bashaw of Tripoli, with whom the United States was at war. The spearhead of Eaton’s force—or, if not precisely the spearhead, at least the visible sign and symbol of United States authority—was a tiny detachment of marines, eight of them in all: one lieutenant, one sergeant, and six privates. The army reached Derne, stormed a harbor fort, and the marines’ young First Lieutenant Presley Neville O’Bannon hoisted an American flag over the captured stronghold—the first American flag to fly over an Old World outpost. That the Bashaw of Tripoli was not unseated but instead was able to make an excellent peace with the Americans took none of the glamour from this exploit. The Marines had indeed been “to the shores of Tripoli,” and the fact was duly noted in the song.

There had been many other fights, too. Marines served in the War of 1812—it was a force of marines and sailors who provided what opposition the British encountered at the Battle of Bladensburg, just before the capture of Washington—and there were marines in Fort McHenry when the unsuccessful British bombardment of that place led Francis Scott Key to write the song that became the national anthem. It is also of record that there were marines with Andrew Jackson at New Orleans, and of course marine detachments served on such ships as the Constitution , the United States , and the Essex .

The marines on the Essex had quite a time. Under the energetic Captain David Porter, the Essex sailed around Cape Horn (where she met such a storm that many of the marines were at one time noticed in an attitude not common in the Corps: on their knees in prayer) and got into the Pacific for a raid on British whalers. The raid was successful, and Porter finally sailed clear to the Marquesas, where he established a base on Nukuhiva Island. Then he sailed off for new adventures, leaving Lieutenant John Gamble, U.S.M.C., [see Cover] with sailors and marines to guard the base and three captured whalers. Gamble was ordered to stay there five months; if Porter did not return, he was then to make his way home. (This marine officer, incidentally, had already shown that he was capable of commanding and navigating a ship.)

Porter was captured by the British and never did return. Gamble’s men, meanwhile, were enjoying a pleasant war, lii’e in the Marquesas being easy and the native girls very friendly; and when the five months ran out hardly anybody but Gamble wanted to go home. There were desertions, and a mutiny, and a fight with the natives—and, at last, Gamble sailed off for Hawaii with a naval midshipman, three sailors, and three marines, all that remained of his original command. A British cruiser gobbled him up in mid-Pacific, and by the time the prisoners were returned to the Atlantic, the war was over.

Between formal wars, the Corps was kept busy. Marines helped destroy pirate nests in the Caribbean in the iSuo’s; they also went all the way to Sumatra, where they made up part of a landing party that, in 1832, stormed and sacked the stronghold of Ouallah Battoo, whose rajah had been making free with American merchant vessels that visited those waters. Some of the Navy’s perennial irritation with the Marines undoubtedly stems from incidents like this: landing parties were usually composed of marines and sailors, but after the dust had settled people had a way of believing that the marines had done it all.

A marine detachment marched to Mexico City with Winfield Scott, in the Mexican War (there comes the “Halls of Montezuma” motif), and had a prominent part in the spectacular storming of Chapultepec. Characteristically, the suppression of John Brown’s uprising at Harpers Ferry in 1859 was accomplished by a detachment of marines (the handiest available force when news of the trouble reached Washington) under the general direction of an army officer, Colonel Robert E. Lee.

The Civil War brought the same problem to the Marines that it brought to the other services: that is, officers of southern birth mostly resigned and went oft to serve the Confederacy. About half of the Marines’ captains and two-thirds of their first lieutenants, according to one historian, gave up their commissions when the war began. Another problem was also shared with the other services. Congress had set up no retirement system for superannuated officers, and many officers tended to be downright aged, since an officer with no income but his pay would never retire voluntarily and there was no way to make him retire except by preferring charges of misconduct. This was at last remedied by an act permitting retirement, on pension, to officers of forty years’ service; a little later, the act was broadened, giving the President discretionary power to retire officers at the age of 62 or on completion of 45 years’ service.

The Corps served in the Civil War, of course, although perhaps less prominently than in some other wars. Farragut used a detachment of marines when he occupied New Orleans in 1862, and a battalion of marines fought at the First Battle of Bull Run, but for the most part the marines performed their service afloat. Actually, the Corps at that period was neither organized nor trained properly for amphibious operations, and landing parties—as at Fort Fisher in 1865—were usually composed of marines and sailors together, with the marines playing no outstanding role.

It was during the years after the Civil War that the Corps emerged with its modern character fully established: as an ever-ready striking force that could be used anywhere. It took part in landings in many, many places: in Formosa and in Uruguay, in Mexico and Egypt and Haiti, in Argentina and Chile and Nicaragua and in North China, in Panama and—away back in 1871, this was—in Korea, where no fewer than six marines won Medals of Honor for bravery. If many of these landings came in support of the “dollar diplomacy” that went out of date as a better understanding of good relations between the United States and other New World nations developed, this does not detract from the extent or the quality of the service rendered. One important factor was that marines could be put ashore in places where the Army could not be used without a formal declaration of war. Technically, the United States was mostly at peace with the nations which were favored by marine landing parties.

Concerning these interventions there has been much argument. That they have profoundly irritated many Latin Americans is undeniable, and that at times they served chiefly to protect certain Wall Street investments is equally undeniable. At the same time, until fairly recently it was taken for granted—in Washington, at least—that if the United States lets no European power intervene in the affairs of any New World nation, it must itself intervene if revolutions bring chaos, bankruptcy, and rioting to an unstable land. Consequently, through more than half a century, it often stepped in to take charge and restore order—in a Caribbean island republic, in Central America, or elsewhere—and when this happened the men who did the stepping were the hard, bronzed marines in their bleached khaki.

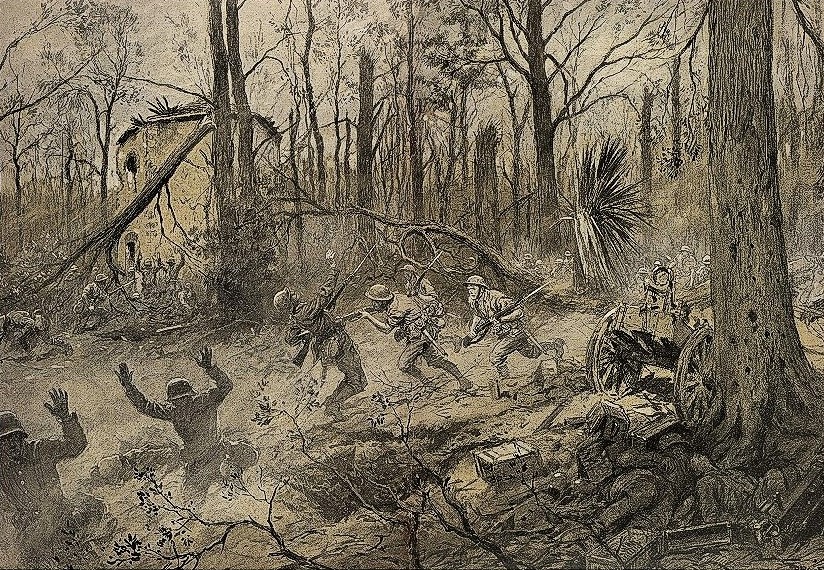

Frequently the intervention was uneventful enough, with nothing required beyond a cruiser or two at anchor in a harbor and a few companies of marines marching from wharf to central plaza. At other times there was hard fighting—as, for example, in Nicaragua in 1912, when after some weeks of occupation duty a battalion of marines, backed by two batteries of marine artillery, stormed a fortified place named Coyotepe Hill, held by rebel troops, near the town of Masaya. It took a bombardment and a spirited frontal assault to accomplish this, and the marines suffered eighteen casualties, but the job was done; and after minor clean-up operations elsewhere in the country, the fighting ended, the rebellion flickered out, and five and one-half months after they landed the marines—except for a legation guard—departed, leaving comparative peace and order behind them.

This was Marine Corps routine, off and on, for many years, and whatever it may have done to America’s relations with other New World nations it had a profound, and beneficial, effect on the Corps itself. It kept the Corps honed to a steady fighting edge; it made veterans out of men carefully selected and rigorously disciplined; and it contributed vastly to that pride in their identity that the Marines have turned into such an asset (and, at times, such an irritant to the other services). The Corps has always liked to repeat the standard report which an admiral, ordered to take a squadron into some sun-baked and riotous seaport, would send back after 24 hours: “The Marines have landed and have the situation well in hand.”

From time to time, efforts have been made to abolish the Corps and quietly absorb the men into the other services. Theodore Roosevelt favored such a move toward the end of his administration, but Congress refused to go along with him; President Taft also tried it, a few years later, without success. The utility of a landing force that was always in a state of readiness was becoming more and more obvious, and experience in the First World War helped clinch things.

At the outbreak of the war Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels offered “equipped and ready, two regiments of Marines to be incorporated in the Army.” He wrote that some army officers were not at all keen to accept this offer, but Daniels presently had his way, and in 1917 the Fifth and Sixth regiments of marines went to France to serve in the Second Division of the A.E.F. as the Marine Brigade.

The Second Division was mostly army regulars, and with these men the tough marines fitted perfectly. One of the most articulate officers who ever served in the Corps, Captain John W. Thomason, Jr. (later a colonel), wrote a book that he called Fix Bayonets! about the Marine Brigade’s experiences in the Second Division, and he left this sketch of the old-timers who served in this brigade:

In the big war companies, 250 strong, you could find every sort of man, from every sort of calling. There were Northwesterners with straw-colored hair that looked white against their tanned skins, and delicately spoken chaps with the stamp of the Eastern universities on them. There were large-boned fellows from Pacific-coast lumber camps, and tall, lean Southerners who swore amazingly in gentle, drawling voices. There were husky farmers from the corn-belt, and youngsters who had sprung, as it were, to arms from the necktie counter. And there were also a number of diverse people who ran curiously to type, with drilled shoulders and a bone-deep sunburn, and a tolerant scorn of nearly everything on earth. Their speech was flavored with navy words, and words culled from all the folk who live on the seas and the ports where our war-ships go. In easy hours their talk ran from the Tartar Wall beyond Pekin to the Southern Islands, down under Manila; from Portsmouth Navy Yard—New Hampshire and very cold—to obscure bushwhackings in the West Indies, where Cacao chiefs, whimsically sanguinary, barefoot generals with names like Charlemagne and Christophe, waged war according to the precepts of the French Revolution and the Cult of the Snake. They drank the eau de vie of Haute-Marne, and reminisced on saki, and vino, and Bacardi Rum—strange drinks in strange cantinas at the far ends of the earth; and they spoke fondly of Milwaukee beer. Rifles were high and holy things to them, and they knew five-inch broadside guns. They talked patronizingly of the war, and were concerned about rations. They were the Leathernecks, the Old Timers: collected from ship’s guards and shore stations all over the earth to form the 4th Brigade of Marines, the two rifle regiments, detached from the navy by order of the President for service with the American Expeditionary Forces. They were the old breed of American regulars, regarding the service as home and war as an occupation; and they transmitted their temper and character and view-point to the high-hearted volunteer mass which filled the ranks of the Marine Brigade.∗ © 1955 Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Well, that is the way a regular officer of the Marines saw them, at a time when they were meeting one of their greatest tests. It has been pointed out that at Belleau Wood in the spring of 1918 the Marines, in mass for the first time, met a professional enemy—and beat him. They did other things, too, of the same order, later in the war, and when the war ended the whole country had heard that marines were great fighting men. (Once again, interservice rivalry rears its irrepressible head. Army people have been known to complain that although the marines were really only a minor part of the famous Second Division, people back home seemed to give them all the credit for everything the Division did; and they add that there were many, many other divisions in the A.E.F. that contained no marines whatever and that made enviable combat records.)

After the First World War there were various alarms and excursions—marines were in sundry Caribbean countries, from time to time, and a certain number of them died there—and then, after a time, there came the Second World War, in which the Corps really came into its own.

Coming into its own meant very hard times indeed for a great many individual marines, for the Corps got some very sticky jobs to handle, all the way from Guadalcanal to Iwo Jima; and the memory of all these things is so recent that it hardly needs to be touched on here, except to remark that in some ways the Marines were the victims of their own reputation: they had established themselves as tough guys, a corps d’élite that could take on anyone or anything, and as a result they kept being given rough assignments, particularly in the far-flung Pacific area. It hardly needs to be said that the Army had many first-rate troops in the Pacific and used them to excellent effect, and that the Navy accomplished marvelous things there against long odds, but somehow there were places where the Marines seemed to steal the show—not because they “got the publicity,” but simply because they could be relied on to send in tough, wholly competent fighting men who would carry out the job given them no matter how many of them got killed trying.

For the Marines not only prided themselves on being tough: they were tough, and their much-talked-of esprit de corps grows out of their consciousness of that fact. One result is that they are forever trying to live up to their own pride in themselves, which can be a mighty force in battle. Another is that they go out of the way to act and even to look like the corps d’élite which they insist they are. They go in for spit and polish, both their dress and fatigue uniforms tend to look snappy and eye-catching, and it is not only the officers who insist on having well-fitted uniforms—the enlisted men want the same thing. A leatherneck private wants his shirt and his tunic to look as if they were made for him personally. He even tends to be something of a dandy—a carefully chosen, thoroughly trained dandy, with two hard fists and with muscles to swing them.

The Marines came out of the Second World War as a highly respected part of the American military establishment, even though war itself was changing so fast that no one had a very clear idea of what a military establishment ought to be like any more. The Marines continue to believe that whatever it may finally be, it will always involve a certain need for topnotch fighting men ready to go at the drop of a hat; they still put great store by hard discipline and ingrained toughness, and once in a while an unhappy training-camp incident will cause sensitive civilians to wince and to wonder whether any military outfit needs to be drilled quite so mercilessly. The Marines continue to carry on in their own way; and the late Colonel Thomason, who was quoted above, summed them up in an anecdote, again from Fix Bayonets!:

They tell the tale of an American lady of notable good works, much esteemed by the French, who, at the end of June, 1918, visited one of the field-hospitals behind Degoutte’s Sixth French Army. Degoutte was fighting on the face of the Marne salient, and the ad American Division, then in action around the Bois de Belleau, northwest of Château Thierry, was under his orders. It happened that occasional casualties of the Marine Brigade of the 2d American Division, wounded toward the flank where Degoutte’s own horizon-blue infantry joined on, were picked up by French stretcher-bearers and evacuated to French hospitals. And this lady, looking down a long, crowded ward, saw on a pillow a face unlike the fiercely whiskered Gallic heads there displayed in rows. She went to it.

“Oh,” she said, “Surely you are an American!”

“No ma’am,” the casualty answered, “I’m a Marine.”