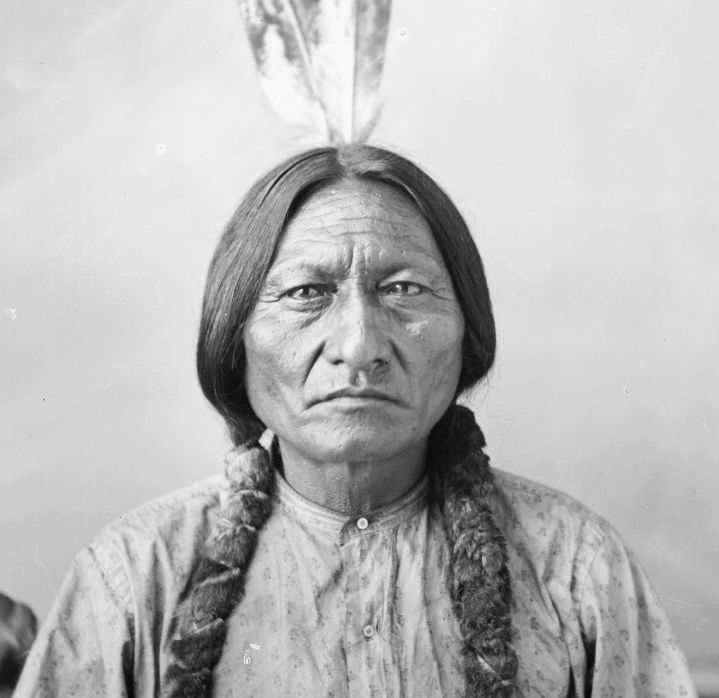

So spoke Sitting Bull, greatest of Sioux chiefs, as he bitterly watched his people bargain away their Dakota homeland

-

June 1964

Volume15Issue4

If Sitting Bull had not put his faith in a miracle, in the fateful winter of 1890, the American struggle with the Dakota Sioux—the last big Indian “war”—might have faded into a peaceful if pathetic accommodation between conqueror and conquered. But a miracle seemed the only refuge for the great old chief in that bitter season of a bitter year; and he thought he saw one coming.

Those of Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapa Sioux tribesmen who clung to him and his dream of preserving the old, free Indian life were in painful distress. Within easy memory they had coursed a domain larger than half a dozen of the white man’s states. Now, restless at the pinch of reservation life near the prescribed Standing Rock Agency in North Dakota, they had followed Sitting Bull to a shabby camp on the Grand River—still on the reservation, but forty miles from white supervision. There, sick with cold, starvation, and white man’s diseases, they watched their lands being snatched away, and sensed the humiliation and perhaps disaster that lay ahead—all under the “protection” of the United States government. In their struggle to preserve their identity as a tribe of hunters, warriors, and nomads, no power on earth seemed to offer any help. Sitting Bull, their extraordinary chief and medicine man, looked for a miracle; and at last one was offered. It was the new Indian religion of the Ghost Dance, which promised a supernatural messiah to sweep the white invader from the western Plains and restore them to the happy custody of the red man.

By the time that grim winter of 1890 settled in, the chief, now in his mid-fifties, had tried all natural, earthly powers. First, of course, war: the native instrument, almost the vocation of his people—a people bred to war as to the hunt, whose art brilliantly adorned their armament, their battle dress, their horses. Their boys started with the bow and arrow at the age of five; their men sang ritually of war and pridefully kept count of each time they struck an enemy. Sitting Bull, himself an eager fighter against unfriendly tribes since the boyhood day when he counted his first “coup,” was renowned for physical courage that was remarkable even among a tribe of fearless braves. A white prisoner of the Sioux told how the chief once led an attack on a war party of Crows: Sitting Bull rode so far ahead that he had leaped from his horse into the midst of the enemy and killed several before the other Sioux even caught up. One of his war songs, chanted as he went into single combat against a Crow chief, goes:

But Sitting Bull was wise as well as brave, and when in the 1860’s the white men came hunting gold in the Sioux hills, although he did not give up fighting, he was willing to try the power of law and diplomacy. The U.S. government was the more ready to talk terms because repeated efforts to clear the trail up to Montana for white settlers had been repulsed with bloody losses. One hopeful embassy to Sitting Bull was carried in 1868 by a frail old priest, Father de Smet, a veteran missionary who was determined to penetrate the troubled heartland of the hostile Sioux and arrange a peace before he died. Long marches brought the priest and his company across the northern Dakota Territory west to the Yellowstone, where the mission was met by five hundred mounted Sioux warriors. There, with pomp and grandeur, they were conducted to Sitting Bull’s lodge. The chief offered peace:

When I first saw you coming my heart beat wildly, and I had evil thoughts caused by the remembrance of the past. I bade it be quiet … it was so. [My people] have been troubled and confused by the past; they look upon their troubles as coming from the whites and become crazy, and push me forward. … I will now say in their presence, welcome father—the messenger of peace. I hope quiet will again be restored to our country. …

But it had to be peace with honor. Sitting Bull would not sell any Sioux lands: nor did he want to see the cutting of any timber—particularly not the oak. He said he loved to look at the oak, which, like the Indian, seemed to flourish in winter storms and summer heat. But an honorable peace the Sioux would respect: and as a token of faith they sang and danced until “the earth shook.”

Thus for a while it seemed that diplomacy might bring the Sioux peace from the white man. The government gave up trying to force a way into the Sioux homeland, and agreed to reserve thousands of square miles, from Wyoming east to the Missouri, for Indian hunting grounds and communal life. On paper, the Sioux could hunt freely even beyond this majestic territory; and no white man might enter their lands without their permission. It seemed that Sitting Bull could now once more lead his braves against the circle of Indian tribes who were traditionally their mortal enemies, while his people followed the old life of hunters and lovers of the natural scene.

Actually, only a few years of the old way were left. Before long, white gold-seekers were filtering through the screen of U.S. troops set up to keep out treaty-breakers. Many of the soldiers themselves deserted as new reports of gold in the Dakotas fired the imagination of westering emigrants. The Sioux took to the warpath, the whites raised cries for help from Washington, and, in violation of the 1868 agreement, large bodies of troops took the trail up through the Black Hills into Montana, intent on eliminating the Sioux war power.

One ironic result was Cluster’s historic defeat on the Little Bighorn in June of 1876—a defeat Sitting Bull, in his role as medicine man, had foretold. But if it was a famous victory for the Sioux, it was a last one. Sitting Bull knew, even as Indian braves counted the spoils of the battle, that they did not have the fighting force to resist the aroused whites for long: and he knew now that there was no meaning in negotiation, for the white man broke treaties as fast as he made them. So, unlike many other Sioux leaders, who were willing to surrender to a life on the reservation, the chief now tried flight.

In May 1877, Sitting Bull led some two thousand of his people to shelter under the power of Grandmother (Queen Victoria) in her vast territory across the Canadian border. They could roam the land, with the privilege of hunting: but game was scarce. The hungry, discontented braves soon began to raid down into the Dakotas: a large group of them deserted. In the meantime, the United States government issued invitations to the Sioux in Canada to return. Sitting Bull was puzzled at these offers: he had not been welcome in the United States before. Why now—when Custer had been killed? But because it seemed to be the best thing for his people, even though his sense of logic went against it, he agreed. In July of 1881, the famous chief put himself and his band in the hands of U.S. troops at Fort Buford, Montana.

Sitting Bull was promised pardon. Instead, he soon found himself loaded onto a steamer and taken as a prisoner to Fort Randall, South Dakota. In the next two years the aging chief learned much about captivity, while his people learned about reservation life. Despite their sadness, many of them accepted government rations with satisfaction. Some allowed their children to go to agency schools. Sitting Bull pondered the changes, and mentally resisted most of them. He was suspicious of the white man’s education, sensing that this struck at the very root of the traditional way of life.

In 1884 there came a new kind of experience for Sitting Bull. With the approval of the Secretary of the Interior, and hoping to discuss the plight of the Sioux with the President, the chief agreed to go on a travelling exhibition in the East. He was paid nothing by Colonel Alvaren Allen, the entrepreneur who organized the tour, but was allowed to sell his autograph, which was eagerly sought wherever he went. The irony of his situation was never clearer than in a Philadelphia theatre, where there happened to be an “educated” Sioux boy in the audience to appreciate it.

The boy (who was to grow up to be Chief Standing Bear) had been surprised to see Sitting Bull billed as “the murderer of Custer”—something he knew to be false, for Sitting Bull did not fight at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Moreover, the chief’s willingness to go on the tour at all implied a conciliatory mood. So the boy paid his fifty cents’ admission and went in to see the show. Sitting Bull, who at that time knew scarcely any English, came out on the stage and said in Sioux:

My friends, white people, we Indians are on our way to Washington to see the Grandfather, or President of the United States. I see so many white people and what they are doing, that it makes me glad to know that some day my children will be educated also. There is no use fighting any longer. The buffalo are all gone, as well as the rest of the game. Now I am going to shake the hand of the Great Father at Washington, and I am going to tell him all these things.

Standing Bear then heard a vicious mistranslation. Sitting Bull, Colonel Allen explained, had been describing his bloody triumph over Custer and his party; and the audience hissed the red villain. As for seeing the Great White Father, the exhibition’s itinerary had never actually included Washington. More broken promises. Yet, if Sitting Bull was made into the epitome of Indian savagery by American hucksters, he did at least change the stereotype for some Americans who observed his quiet dignity, or saw him give pennies to ragged white children. Buffalo Bill Cody, who signed up Sitting Bull for his Wild West show the following year, found that in dealing with the chief a white man must keep his word—absolutely.

When Sitting Bull returned to his own people at Standing Rock Reservation in 1885, he brought with him a gift—Buffalo Bill’s trick horse. He had learned that there were some white men prepared to be friends to the Indian. Now, however, he rediscovered how vulnerable his people were to the crowds of whites who were flowing into the Sioux reservation, hungry for gold and land. The huge acreage already given up by the Sioux was not enough: why leave the rest of this rich land in the hands of ignorant savages? It was perfectly clear to Sitting Bull that his own medicine (his apparent power to change weather, to predict events) was too weak and that, unless something greater came to their aid, his Sioux must become a defeated people in an occupied country who could survive only by aping their conquerors.

In the 1880’s he had to watch repeated attempts to buy, wheedle, or steal the Sioux reservation. While he was still a prisoner at Fort Randall, in 1882, the Sioux were offered, after an intense barrage of government propaganda, eight cents an acre for much of their territory. The deal was forestalled only by determined Indian opposition and the fact that even Congress became alarmed at the greed of the government negotiators. Sitting Bull, always a dominant voice in the Sioux councils, spoke out firmly against any agreements, and indeed any negotiations, until the old promises, so long ignored, were kept. He wanted to hang on to every Sioux acre until the new generation had enough education to deal with the whites on their own terms. Now his people were helpless and naïve in the hands of the invaders: “We are just the same as blind men, because we do not understand them.” He fenced stoutly with the land commissioners, learned to understand better and better what was hiding behind their words, and endeavored, sometimes angrily, to explain why his people needed their land, almost as birds needed air. The commissioners, knowing him to be against “progress,” tried to ignore his stature in the Indian community. He insisted on it. As he explained it to a Senate investigating committee in 1883,

I am here by the will of the Great Spirit, and by his will I am a chief. My heart is red and sweet, and I know it is sweet, because whatever passes near me puts out its tongue to me; and yet you men have come here to talk with us, and you say you do not know who I am. I want to tell you that if the Great Spirit has chosen anyone to be chief of this country, it is myself.

A senator baited him, saying there was no need to recognize chiefs designated by spirits and Indians; and the fierce old Hunkpapa threw the conference into a turmoil by telling the senators that they must be drunk. But his concern for his people overcame his anger, and he came back to apologize.

If a man loses anything and goes back and looks carefully for it he will find it, and that is what the Indians are doing now when they ask you to give them the things that were promised them in the past; and I do not consider that they should be treated like beasts, and that is the reason I have grown up with the feelings I have. … You white men advise us to follow your ways and therefore I talk as I do. When you have a piece of land, and anything trespasses on it, you catch it and keep it until you get damages, and I am doing the same thing now … I am looking into the future for the benefit of my children, and that is what I mean when I say I want my country taken care of. … I sit here and look about me now and I see my people starving … our rations have been reduced to almost nothing, and many of the people have starved to death. Now I beg of you to have the amount of rations increased so that our children will not starve. …

In 1888, millions of acres were again demanded, at fifty cents an acre. When the Sioux still proved cold to the offer, a party of great chiefs (including Sitting Bull) was brought to Washington for further pressure. Again they resisted. But in the ill-omened year 1889, new commissioners arrived in the Dakotas, offering $1.25 per acre for 16,000 square miles—and behind them were whites agitating to take the land if it couldn’t be bought.

Frustrated by the stony resistance of the famous chief, fearful that he would prevent the Sioux from voting to concede the land, the commissioners resorted to intrigue. Working through Major James McLaughlin, director of the Standing Rock Agency, they singled out four susceptible chiefs, carefully keeping them apart from Sitting Bull until the moment of decision came. Through them, the commissioners tried to pressure the braves into yielding the necessary number of signatures—by treaty, three quarters of the total was required—before Sitting Bull could rally an opposition. Some of the Sioux, now dimly in touch with a money civilization, inflamed by the chance to buy the white man’s clothes, whiskey, and other goods, and above all hungry for better food, were pleased to barter their birthright. Others signed without understanding what they were doing. Still there were not enough signatures; and in a hurried, ambiguous procedure which McLaughlin later described evasively—and which many Indians were to call fraud—two hundred more signatures were quickly obtained. It was announced that the deal had been completed. Sitting Bull felt betrayed: he had not even been allowed into the meeting where the last signatures were gathered. When asked how the Indians felt about the affair, he replied bitterly, “There are no Indians left now but me.”

Toward the end, nature itself seemed to join the forces closing in upon Sitting Bull and his Sioux. As they settled down to wait anxiously for their land money, the weeks passed; the months; the cruel winter of 1890 came, and the Indians were empty in stomach and pocket. In 1888 they had lost much of their crops because the commissioners kept them long in conference at harvesttime, while hungry stock broke into their fields; in 1889 and ’90, their land had withered in a terrible drought. The game animals, particularly the buffalo, had been irremediably depleted by white hunters, and the savage winter further reduced the short supply of game on the Sioux reservations in the Dakotas. Between 1886 and 1889 their promised supplementary meat ration had been cut by more than half, according to General J. R. Brooke, on the theory developed in Congress that a hungrier Indian would make a better farmer. In 1890, this shrunken version of an inadequate ration again was drastically cut when, in direct defiance of government regulations, winter-grazed cattle were supplied to the Dakotas. Winter cattle might weigh half as much as summer ones, and were mainly skin, bones, and hoofs. Starvation moved into the camps of the Sioux, an intimate enemy.

Meanwhile a single human opponent was using all his skill and influence to undermine Sitting Bull personally. This was the agent McLaughlin, himself married to a woman of Indian blood, and a stout believer in converting the Indians to civilization and progress. A better man than most Indian agents, he had never supported the savage frontier proverb, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian”; but he was firmly convinced that the only good Indian was one who copied the white man and did what he was told. His own job, he said, was to put “the raw and bleeding material which made the hostile strength of the Plains Indians [through] the mills of the white man … transmitting it into a manufactured product that might be absorbed by the nation without interfering with the national digestion.” He accepted the easy division of Indians into the “friendlies” or “progressives”—agency Indians ready to conform to white man’s schooling and culture—and the “hostiles,” who still wanted to live in the old way. The agent had quickly recognized Sitting Bull as a dangerous “hostile,” a center of disaffection especially among those Sioux who lived in the more remote areas of the Standing Rock Reservation.

But beyond this, McLaughlin felt a strong personal irritation: Sitting Bull was the only important chief who would not yield to him. His account of his relations with Sitting Bull is a curious mixture of grudging admiration for the chief’s influence over other Indians, and bitter resentment of his intransigence. Photographs and paintings of Sitting Bull show a face of dignity, even of majesty; General Nelson Miles, who had opposed him in the field and in conference, found him “a fine, powerful, intelligent, determined-looking man … cold, but dignified and courteous.” But to McLaughlin, he was an unreconstructed troublemaker with “an evil face and shifty eyes.”

McLaughlin set out to break him. He intercepted and read Sitting Bull’s mail, and used the press to create an aura of scandal and villainy around his name. Closer to home, he hurt the old chief directly. McLaughlin controlled what rations there were to give away, and when Sitting Bull’s followers came for theirs, they saw the power and comfort of McLaughlin’s camp, the strength of the army troops stationed there, and heard the assurances of “the Grandfather’s” wish for their security. More invidiously, the agent offered a tempting activity to the Sioux warriors, restless and brooding without the war and the hunt. To those who would defect from Sitting Bull—some jealous of the old man’s authority, some dazzled by the white way of life—he gave blue uniforms and brass buttons, and put them into an Indian police force that kept watch on the Indians in Sitting Bull’s Grand River camp.

At this crucial time—when the aging chief’s power seemed to dwindle, when the forces of the earth seemed to be closing in on him and his free Hunkpapas, when it seemed that only a miracle could save him and his dream of the old independence—there came the Ghost Dance.

Far to the West, in Nevada, a Paiute named Wovoka had had an apocalyptic vision of the Christian heaven, and had offered the promise of a second coming of the Messiah. His full blessing was coming soon , in the next spring, the spring of 1891, and this time, directly to the Indians —and indeed why not? He had appeared first to the white man, and look how the white man had treated him! Now the Indians would dance him back to a better reception—and a return of their rightful hunting grounds.

Wovoka’s grand vision sprang in part from a dormant dancing religion aimed at communication with the dead; it flowered into a dream of a heaven on earth for the Indians, and spread over the Plains like a wind. By the fall of 1890, Sitting Bull’s nephew, Kicking Bear, had gone with other Sioux ambassadors to visit Wovoka, and had come back with marvelous tales: the Sioux had been led “way up a great ladder of small clouds … through an opening in the sky” until they came to “the Great Spirit and his wife … Then from an opening in the sky we were shown all the countries of the earth.” The Great Spirit promised that the Indians would now be his chosen people, if they obeyed him.

All the frustrated fantasies of the conquered western Indians went into this new religious dream: the Messiah would not only appear to living red men, but would also bring back to the world the dead ones, and the vanished buffalo, and the shy, frolicsome antelope; the Indian would be a free master of his lands again, and perhaps a great catastrophe would sweep away whites and renegade Indians, and bury them under the ground, five times as deep as the height of a man. Wovoka himself preached peace. But the Sioux around Sitting Bull, with an eye to their white enemies, nevertheless found war-magic in the new religion, enough to throw panic into the white West. Their neighbors and allies, the Cheyenne, also took up the new magic with fervor.

The basic ritual was the frenetic Ghost Dance itself. Around a tree hung with prayer cloths, the dancers spun in a huge circle, shouting, screaming, building up to a hypnotic frenzy. Then one dancer, and another, would fall to the ground in a trance. These were the lucky ones: they would leave their bodies to visit the Messiah. When they came back to the physical world, they would have messages from the spirit world for the other dancers—insights, explanations, promises. The promises grew, and were elaborated. And one fantasy in particular, an old, familiar dream of the Indian brave, was seized upon by the battle-starved warriors of the Sioux: a miraculous shirt, the flimsy cotton Ghost Dance shirt, sometimes emblazoned with magic symbols—the sun, the moon, the stars, other nature signs—which would make the wearer bulletproof.

This magic of invincibility, made doubly sure because the Messiah was expected to render the white man’s gunpowder useless, lent a weird, dangerous note to the hysteric religion. Many whites in the Dakotas were fearful of a holy war against them, led by fanatics certain they could not be killed; some settlers fled the area. The alarm soon spread to Washington. In November, army reinforcements were sent, and on December 3, 1890, a resolution was offered in the Senate authorizing the Secretary of War to issue the governors of North and South Dakota each a thousand rifles and fifty thousand rounds of ball cartridges, to be distributed to citizens and militia for protection against the Indians.

A few voices spoke for the Sioux and the Cheyenne. Senator Daniel Voorhees of Indiana rose to call the government policy “a crime, revolting to man and God.” He reminded a hushed Senate that General Miles had said the Indians were being “starved into hostility.” The Sioux needed feeding, not fighting: “If the proposition were to issue one hundred thousand and more rations to the starving Indians, it would be more consistent with Christian civilization.” The Secretary of the Interior urged Congress to feed and pay the Indians according to promises already made. Congress would take the necessary action—much too late.

The violence toward which white and red men were headed was fed by passions on both sides. The Indians, and especially Sitting Bull, were made figures of terror in much of the nation’s press: the old chief was “that wily medicine man,” “sagacious, cruel, and bloodthirsty.” On their side, the Indians were near desperation. A cold November had given way to an icy December; there was no relief, and the discontent and restlessness of the Sioux and the Cheyenne steadily mounted, the more so because they were sickening and dying from epidemics of “white” diseases like “grippe,” whooping cough, and measles. There were three centers of disaffection: under Sitting Bull, at his Grand River camp in the Standing Rock Reservation; under Red Cloud, at the Pine Ridge Reservation near the Nebraska border; and, between the two, under Hump and Big Foot, on the Cheyenne River Reservation. More and more they danced the Ghost Dance, clamored for the old glory promised them, and complained about inadequate rations. Some of the Cheyenne Indians simply stole cattle when insufficient food was given them.

It was that or starve, as General Miles would point out; but white tempers were naturally aroused. Efforts were made to outlaw the Ghost Dance, and this interference with their religion further irritated the Indians. McLaughlin, Sitting Bull’s adversary, felt he could handle the situation at Grand River if he could get the chief out of the way. He had already recommended his removal through official channels. Cautious, Sitting Bull was not coming to the agency now, even for his own rations. He sat and pondered the only hope left to him: the new religion. He seems to have been skeptical when Kicking Bear first brought the revelation of the Messiah. Yet it fitted exactly the dreams and hopes of the Indians; and perhaps it seemed to promise him the renewed leadership of his free people …

True, there were disturbing rumors of miracles that didn’t come off, of a dancer who tested a bulletproof shirt, and was wounded; and some believers fell away, wooed by the agents and agency Indians. But the “hostiles” generally held firm because they needed faith so desperately. Throughout late November the fanatic dances had excited Sitting Bull’s camp, growing in frequency and intensity, and he waited for a sign. For it now seemed that the Messiah, concerned for his troubled people, might not wait for spring, but would come soon, perhaps any day.

It had to be soon. The Plains Indians, alarmed by the influx of army troops, particularly of the Seventh Cavalry, Custer’s old command, were apprehensive of a revenge massacre that would wipe them out. Many Sioux, under Kicking Bear, fled to shelter in the Bad Lands. There was a sense of climax in the country, and even the agency Indians grew fearful, and felt the pull of the dancing rituals and the Messiah’s promises brought to them by evangelical “hostiles.” McLaughlin, troubled by the mounting tension, sent some of his police to Sitting Bull to woo his camp away from the new religion; the police came back almost converted themselves. Then McLaughlin went in person to persuade the Hunkpapa that the Ghost Dance was a false religion. Sitting Bull heard him, and suggested a test that had been in his own mind:

Father, I will make you a proposition which will settle this question. You go with me to the West, and let me seek for the men who saw the Messiah; and when we find them, I will demand that they show him to us, and if they cannot do so, I will return and tell my people it is a lie.

McLaughlin refused pointblank; he said this would be like trying to catch up with the wind that blew last year. The confrontation ended in a stalemate, although McLaughlin went back to his agency convinced that Sitting Bull was perhaps in a less belligerent state of mind than had been imagined.

Here a note of comic relief enters the tragic story. General Miles, the military officer responsible for containing the northern Plains Indians, had decided that isolation of the disaffected chiefs would be one corrective measure, and he issued an order for Sitting Bull’s arrest. He issued it, however, to a mutual friend —Buffalo Bill Cody. Apparently the idea was that the two old companions of the Wild West exhibition might talk things over, and that Sitting Bull might then put himself more or less willingly under detention at the Standing Rock Agency.

The plan, such as it was, worked out badly. McLaughlin not only resented Buffalo Bill’s intrusion, but felt that the moment for Sitting Bull’s arrest had not yet come. He therefore arranged for some of the army officers at nearby Fort Yates to entertain Cody with extensive liquid refreshment while a telegram went off to Washington to get an order countermanding Buffalo Bill’s authorization from General Miles. The following day, with the famous showman fighting off what must have been a formidable hangover, McLaughlin had one of his assistants intercept him on the trail to Sitting Bull’s camp, and convey the false impression that the mission was too late: that the Indian chief had already gone to the agency of his own accord. By the time Cody got back there himself, the countermanding order had arrived from Washington, and McLaughlin was once more in control of the situation. The tragic crescendo of events resumed.

Now Sitting Bull made a crucial move. He wanted desperately to see the Messiah, and word had come that the savior would appear at Pine Ridge—soon. In his law-respecting way which was so frustrating to McLaughlin, he wrote asking the agent for permission to travel. Then he started making preparations for the journey to the Pine Ridge Reservation. The report of his movements quickly reached the agency through McLaughlin’s spy network. McLaughlin was alarmed: he could not allow the appealing, powerful personality of the “cunning and malignant” chief to influence the other Indians. Fortunately, from his point of view, orders were received on the twelfth of December finally authorizing the army troops and the agency to bring in the Hunkpapa chief. The arrest had been scheduled for December 20, but now it was set in motion at once.

Sitting Bull had planned to leave for Pine Ridge on December 15. On the night of the fourteenth he went peacefully to sleep in his cabin, with his favorite son, Crowfoot, nearby. The huge horseshoe of the ghost dancer tepees was silent, and in the corral the horses shuffled restlessly to combat the blood-slowing frost. In their quarters a few miles away, the local members of the Indian police force were restless too: the order to arrest the great Hunkpapa chief had been translated to them. They had been picked for their loyalty to the agency and to the new civilization, and for their willingness to thwart the “hostiles”; they were to be led by Lieutenant Bullhead, known to have bad feelings toward some of Sitting Bull’s braves. But their hearts were troubled.

“When everyone was ready,” Lone Man, one of the policemen, said in his account of that night, we took our places two by two and at the command “Hopo” we started. We had to go through rough places and the roads were slippery. As we went through the Grand River bottoms it seemed as if the owls were hooting at us and the coyotes were howling around us, and one of the police remarked that the owls and coyotes were giving us a warning. “So beware,” he said.

Lone Man explained that the forty-three police on the mission felt sad to think that the chief had disobeyed orders “due to outside influence,” and so had to be arrested. As for Lone Man himself, he rode along expecting “big trouble.”

Back at the Fort Yates army barracks, Captain E. G. Fechet, in charge of military support for the arrest action, had recovered from his momentary surprise at the speed-up in plans. He and two troops of cavalry, heavily armed and pulling a Hotchkiss gun, had moved out at midnight for their rendezvous with the Indian police. They had over thirty miles to go.

The Indian police filtered into Sitting Bull’s camp in the early hours of the morning, and found their way to the chief’s silent house. As dawn broke, Lieutenant Bullhead knocked sharply at the door, and pushed in. Sitting Bull awoke to find himself beleaguered.

For much of his fifty-six years the chief had commanded these Sioux braves; now they were laying hands on him as if he were a common criminal. Yet he still made no overt resistance; he agreed to dress, and to come with them. They hurried him: they wanted him out, and on his horse, and away, before the camp was aroused. They knew his warriors were fiercely loyal and would be furious at this treatment of a chief. But the alarm was sounded, probably by barking dogs and the lamentations of one of Sitting Bull’s women.

History diverges here; there are many accounts, some justifying and some condemning the subsequent action. The loyal Hunkpapa, running to the aid of their chief, were fended off by the police, led by Bullhead. The official government account says that faithful Catch-the-Bear fought his way into the group, raised his rifle, and shot Bullhead. Bullhead, severely wounded, turned and shot Sitting Bull in the chest. In the gray dawn a bloody fight now developed; and at this point the troops from Fort Yates arrived. Captain Fechet added horror to the chaos by dropping shells from the Hotchkiss gun on the camp and into the nearby timber where some of the ghost dancers had fled. In the din and confusion, a truly ghostly thing happened: Sitting Bull’s trick horse, taking his cue from the shooting, thought himself back at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, and all alone, riderless, went through his tricks. His master lay dead—shot, beaten, and mutilated by the furious police.

“The object of the expedition,” Captain Fechet wrote in an unofficial report, “had been more than accomplished.” Was it, then, to kill Sitting Bull? From Standing Rock next day came apparent confirmation, as printed in the New York Herald:

It is stated today that there was a quiet understanding between the officers of the Indian and military departments that it would be impossible to bring Sitting Bull to Standing Rock alive, and that if brought in, nobody would know precisely what to do with him. … There was, therefore, cruel as it may seem, a complete understanding from the Commanding Officer to the Indian Police that the slightest attempt to rescue the old medicine man should be a signal to send Sitting Bull to the happy hunting ground.

If most of white America was pleased by the killing, in the Dakotas it was a signal for alarm and flight for all the “hostiles,” now convinced that slaughter by the whites was at hand. When refugees from Sitting Bull’s camp reached Big Foot on the Cheyenne, that chief started a quick retreat into the Bad Lands. He was met by army troops at Wounded Knee with assurances of safe conduct and fair treatment; but the soldiers insisted on surrender of the Indians’ weapons. The braves held back; there was an incident—and a chaotic and furious battle followed. Men died on both sides, but the odds were hopelessly against the Sioux. The troopers poured fire pointblank at the encircled Indians, and in the confusion many women and children were killed, together with nearly a hundred Sioux warriors.

After the tragedy of Wounded Knee, some Indians who had been lured back to the agencies from the Bad Lands fled again; and others from Pine Ridge, certain now of being massacred, went with them. The skirmishing dragged on three more weeks before the military under General Miles could convince the frightened Indians that Americans meant peace. By then it was mid-January 1891—the year the Messiah had promised to come to the Sioux.

Sitting Bull’s bruised and mutilated body was given a secret burial, without the honors his rank and record might have won him. “His tragic fate was but the ending of a tragic life,” General Miles observed. “Since the days of Pontiac, Tecumseh, and Red Jacket no Indian had had the power of drawing to him so large a following of his race and molding and wielding it against the authority of the United States. …” But Sitting Bull had needed a miracle; and there was none.