In Florida during the 1830s, a young Indian warrior led a bold and bloody campaign against the government's plan to relocate his people west of the Mississippi River.

-

Summer 2012

Volume62Issue2

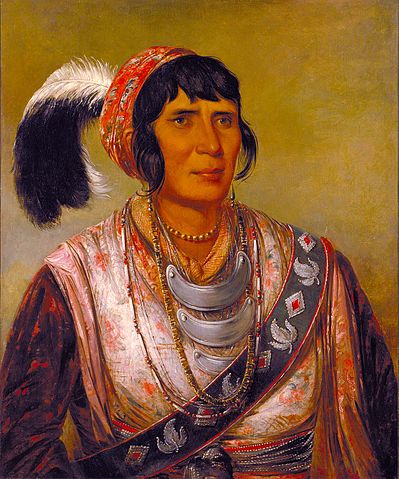

The story of Osceola and the Great Seminole War in Florida seems so fantastic at times that it is hard to believe it is all true. One warrior with courage, cunning, and audacity unsurpassed by any Native American leader masterminded battle tactics that frustrated and embarrassed a succession of U.S. Army generals.

Osceola initiated and orchestrated the longest, most expensive, and deadliest war ever fought by Native Americans. He embarked on this quixotic struggle not for glory or out of hatred for the white man, but simply because he believed his people were being treated unjustly. Osceola had not always been a member of the Seminole tribe, nor had he always lived in Florida. He was born Billy Powell around 1804 in the Creek town of Tallassee, near present-day Tuskegee, Alabama. Like many Creeks of his generation he was of mixed parentage—a Scottish-English father and a Creek mother.

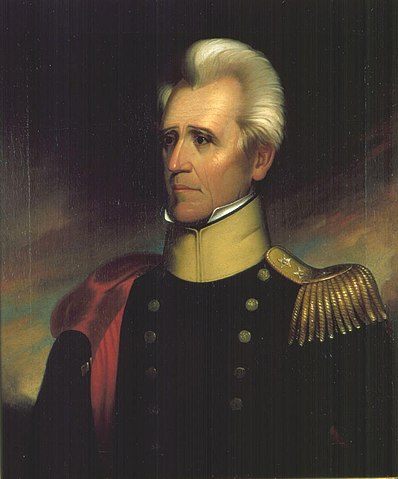

Between 1812 and 1814, the Creeks living along the Tallapoosa River, which included the Powell family, rose to defend their land against encroaching white settlers. The U.S. government, already involved in the War of 1812, mustered a militia under the command of Gen. Andrew Jackson to come to the aid of the settlers. Jackson and his men laid waste to the territory, attacking and destroying Creek towns.

The Powell family and their neighbors were forced to flee. Impoverished and desperate, they drifted south, living off the land. In time, these Creek refugees arrived in Spanish Florida and settled near present-day Tallahassee. The area was inhabited by the Seminoles, whose culture resembled their own in most respects.

The Seminole Nation was not a distinct tribe with a long heritage but instead had been formed from various Native American tribes that had migrated down from the north and banded together. They also invited runaway slaves to join them.

The Creek newcomers felt heartily welcomed and enjoyed a period of peace and prosperity. The tribe owned herds of livestock, the luxuriant Florida climate produced an abundance of food, and goods from British and Spanish traders were readily available.

For years, however, the Seminoles had been raiding white American settlements along the Georgia and Alabama borders. Once again the government called on Andrew Jackson, who led a large force into Florida and eventually marched on the village where Billy Powell and his mother lived and burned it to the ground.

Billy, now 14 years old, got a firsthand taste of U.S. military power when he was captured and held briefly before being released unharmed. Jackson’s invasion ended the prosperity of these Seminoles, and Billy and his mother uprooted once more and moved to the Tampa Bay area.

There, Billy officially passed into manhood at the Seminoles’ Green Corn Dance, a ceremony of purification, forgiveness, and thanksgiving held every summer. During the event, men consumed an herbal tea known as the black drink. Billy shed his childhood name and took the name of the wordless song that accompanied the serving of this drink. He became Asi Yaholo—Osceola—“Black Drink Singer.”

In 1819, Spain turned Florida over to the United States. Native Americans who had fled south were once again living in U.S. territory. The government began openly discussing a plan to move the Seminoles from Florida to an area west of the Mississippi River. The threat of relocation caused Chief Micanopy to seek a compromise. In 1823, the Seminoles grudgingly agreed to the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, under which they would remain in Florida but give up 28 million acres of traditional homeland in return for about 4 million acres in the marshy Florida interior, land difficult to farm and short of animals to hunt.

By this time, Osceola was a highly respected tustenugge, or policeman, of his band. He had established a cordial relationship with white authorities with whom he came in contact. In 1826 the 22-year-old became enamored of a young woman named Che-cho-ter, or Morning Dew. Accounts suggest that she was at least part-black, either a former slave or a descendant of a runaway. The couple, alas, was not to live happily ever after.

In 1828, Andrew Jackson was elected president. He viewed the Seminoles as an obstruction to progress and pushed his Indian Removal Bill through Congress to relocate Eastern tribes west of the Mississippi River once and for all. The government met with a delegation of Seminoles at Payne’s Landing on the Ocklawaha River to negotiate a treaty for the removal. Details of the meeting are sketchy, but the Seminole tribe apparently agreed to move from Florida.

Up to that point, Osceola had shown little interest in the politics that had affected his nation, but what transpired at Payne’s Landing in 1832 deeply affected him. When Seminole chiefs acquiesced to the removal, the young tustenugge began rallying his fellow Seminoles to the cause of resistance. He believed the treaty would lead to the annihilation of their nation. With Morning Dew no doubt in mind, he stressed a provision in the treaty that black Seminoles would be seized and returned to slavery. The chiefs finally agreed with Osceola and vowed to fight rather than allow the people to be removed from their homeland.

At the same time, Indian agent Wiley Thompson, the government’s chief representative, summoned Seminole leaders, including Osceola, to Fort King to sign a contract reaffirming their acceptance of the Payne’s Landing treaty. To Osceola’s consternation, 16 chiefs, ignoring their pledge to him to fight, signed the contract, agreeing to deliver their people to Tampa Bay for removal. Outraged, Osceola rose to his feet and strode forward, thrusting his knife into the treaty paper. He loudly vowed, “This is the only treaty I will make with the whites!”

Thompson instantly ordered his guards to seize Osceola and place him in irons in the fort’s prison. Osceola knew that he could be of no help to his people while confined. The next morning, he promised Thompson he would sign the paper if he were released. As a reward for his apparent cooperation, the influential young leader received a gift from Thompson of a silver-plated Spanish rifle, a superior firearm at the time. Osceola, however, had not abandoned the cause.

In November 1835, Chief Charley Emathla, Thompson’s most important ally in the tribe, was preparing for his departure to the West when Osceola confronted him. The two men argued, and Osceola, who considered Emathla a traitor, shot him dead. Osceola continued his violent protest of the Payne’s Landing treaty by leading his band on a series of raids against white settlements, resulting in casualties on both sides.

On December 23, a column of 110 officers and men led by Major Francis Dade marched out of Fort Brooke on its way to Fort King, following a trail recently hacked out of central Florida’s dense scrub. A group of Seminoles under the overall command of Osceola, but being led by a warrior named Alligator, shadowed the column. Osceola had pushed ahead to Fort King, where he waited in concealment near the main gate. When Wiley Thompson walked through the gate, a bullet struck and killed him. It came from Osceola’s Spanish rifle.

In effect, Osceola had declared war. He now hurried to join Alligator’s force of some 200 warriors hidden among the palmettos on one side of the road. As the army column approached, marching two by two, over-coats buttoned over their muskets to protect them from a cold drizzle, Alligator attacked, before Osceola had time to reach them. The screaming warriors fired into the surprised troops at point-blank range. The entire left side of the column—half of the total force, including Maj. Dade—fell dead in the initial volley. By nightfall all the soldiers were dead except for one, who managed to crawl through the swamps and make it back to the fort to tell the tale.

Osceola was far from finished.

A few days later a force of 250 regulars under General Duncan L. Clinch, along with 500 Florida volunteers led by General Richard K. Call, marched out of Fort Drane with the intention of invading the Seminole settlements along the Withlacoochee River. On the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, the column crossed the river, halting to rest about 400 feet inland in a horseshoe-shaped clearing flanked by thick hammock.

Osceola, who wore a blue army officer’s jacket as a show of contempt, had assembled about 250 warriors. They moved into position in the underbrush on two sides of the unsuspecting soldiers. He gave the order—a loud war-whoop—and the warriors commenced firing on the unsuspecting troops. The soldiers panicked, but Clinch managed to form them into ranks, and they returned fire.

During the fight, a bullet struck Osceola in the arm. Although the wound was relatively minor, it greatly disturbed the warriors to see their leader injured. The battle seemed to be a stalemate, and Osceola ordered his men to melt back into the palmettos. The Battle of the Withlacoochee was, in fact, another victory for Osceola. The soldiers had suffered four dead and scores wounded, compared with three dead and five wounded for the Seminoles. More importantly, the tribe had repulsed an invasion of its homeland.

Public outrage over the Florida losses elicited a swift response from Congress. In January 1836, a hero of the War of 1812 and future presidential candidate General Winfield Scott—the most highly regarded officer in the U.S. Army—assumed command in the Florida Territory. Scott arrived vowing to crush the uprising in a few months. He devised a three-pronged pincer movement to catch the warriors in their camp and destroy them.

Scott was unaware that General Edmund Gaines, commander of forces in Louisiana Territory, had led about 1,000 troops into Florida in response to the Dade Massacre. On February 26 Gaines and his men reached the fording place on the Withlacoochee that had been the site of Osceola’s ambush of generals Clinch and Call.

Gaines was met at the ford by sustained rifle fire from the Seminoles, the first shot killing Lt. James Izard. Osceola’s men kept the soldiers pinned down the entire day. The troops managed to build a breastwork of logs to hide behind, christened Fort Izard for their fallen lieutenant, and Gaines dispatched a messenger through the lines to seek help. At dawn, Osceola resumed the attack. For eight days the siege of Fort Izard continued; 32 soldiers were wounded, many of them severely.

Osceola held the overall advantage in the war and certainly in this siege, but he wanted to end the bloodshed. He knew that the army could withstand a long war far more easily than his people could. They were already feeling the effects of hunger and illness. He requested a parley with General Gaines, who with several officers met with the Seminoles outside the breastwork. Osceola offered to cease fighting if the general would promise that the Seminoles could remain in their homeland.

Gaines was in a quandary. He did not possess the authority to arrange such a treaty. Yet, if he refused the terms, he and his men would likely be slaughtered.

At that moment, to everyone’s astonishment, General Clinch marched into the clearing with a company of reinforcements and began firing on the warriors. Osceola ordered his men to fall back. The cease-fire—and the siege—were over. Osceola’s first attempt at a negotiated peace had ended in a hail of gunfire.

General Scott did finally attempt his three-pronged pincer attack, but Osceola skillfully maneuvered his people through the swamps and eluded all three enemy detachments. Scott’s campaign was an unmitigated failure, and the press called for him to resign his command, which he did. Gen. Richard Call, now the new governor of Florida, decided to personally lead the militia against the Seminoles.

In the summer of 1836, soldiers at Fort Drane began to contract malaria, a potentially deadly disease, and were ordered to move to Fort Defiance. Osceola and his men then occupied the vacated fort, making it their base of operations.

Governor Call was determined to destroy the Seminoles. In mid-November, he attacked two encampments, killing 45 tribe members. His men were low on rations, so Call withdrew, but he was satisfied that he had administered a damaging blow. Higher authorities disagreed, and Call was informed that he had been relieved of command. The new commander was yet another general, Thomas Jesup, a firm believer that “the end justifies the means.”

Among the United States public and in the press, the Seminole War was no longer a popular cause. Soldiers told stories about the horrible conditions they had endured—diseases, poisonous snakes, and marches through swamps in chest-deep water. Osceola was now regarded as an honorable warrior fighting for a righteous cause. People toasted his health: “To the still unconquered red man.”

General Jesup was not swayed. The fight would go on. He understood that small bands of Seminoles could attack his forces at will with few losses, so he changed his strategy, moving his troops through the territory like beaters in a pheasant hunt. Slowly but surely Jesup’s method reaped rewards. In the course of one month his troops killed dozens of warriors, destroyed camps, confiscated pony herds and supplies, and captured runaway slaves, who were shipped back to their masters or sold to defray the army’s expenses.

Part of Jesup’s success had to do with Osceola contracting malaria at Fort Drane. While he battled the disease, he exhorted his warriors to fight to the last man rather than leave Florida, and they renewed their attacks.

The stubbornness of the Seminoles, inspired by their leader, finally convinced Jesup that the solution for a quick end to the conflict was to negotiate a treaty. In March 1837, he persuaded several influential chiefs—who claimed to speak for Osceola—to meet with him. Jesup told them that if they would agree to migrate, he would allow their black brethren to accompany them. Most of the tribe agreed to the new treaty.

Osceola and his followers, however, had not given up. On the night of June 2, the leader and a party of warriors crept to the gates of the Tampa detention center. Without a shot being fired, they freed the 700 Seminoles held there—including several chiefs who had been taken away by force.

Osceola’s audacious act directly challenged Jesup’s authority, and the furious general now declared that the only course of action was to kill every Seminole in Florida. As an incentive, he told his troops that any fugitive slaves they captured would become their personal property.

Jesup’s right-hand man, Brigadier General Joseph Hernandez swept through the territory with his militia, raiding the makeshift Seminole settlements. His forces killed and captured enough Seminoles to undermine Osceola’s ability to muster warriors.

By mid-October, Osceola realized that his people could not fight much longer. And, once again, he decided to initiate treaty negotiations. He sent a message to General Hernandez.

On October 27, a white flag of truce was flying above Osceola’s camp when General Hernandez entered. Throughout the war, the white flag had been flown by both sides from time to time, and both sides had respected its meaning.

Hernandez asked the Seminole leader if he intended to cooperate with the government. Osceola did not have a chance to reply. Hernandez gave a prearranged signal, and his troops, who had silently encircled the camp, burst in and seized Osceola and his companions. The captives were marched away to the prison at Fort Marion in St. Augustine.

News of the capture of the famous Seminole enthralled the nation. The nature of his capture, under a flag of truce, sparked protests against the conduct of the war—and remains a controversial subject to this day.

Osceola was eventually transferred from Fort Marion to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina. The repeated loss of his homelands combined with his bleak imprisonment and separation from his people in their continuing conflict broke Osceola’s spirit and affected his already weakened health.

On January 30, 1838, three months after his capture, the 34-year-old Osceola was dying. With great difficulty, he stood up, dressed himself in his finest clothing, then lay back down on his prison bed. He crossed his arms on his chest, and a few minutes later, he was gone.

At the time of his death, Osceola was the most famous Native American in the country, and his demise was splashed across the front pages of newspapers worldwide.

The Seminoles continued to resist removal, but by mid-century as few as 100 members of the tribe remained in all of Florida. It was not until 1934 that the remnant tribe became the last Native American group to formally end hostilities with the United States.

Today, Osceola is rarely mentioned in the same conversation as Geronimo, Sitting Bull, or Crazy Horse, but there is no doubt that his impact equaled that of any Native American leader who stood up to challenge the might of the United States government and army, seeking the rights of his people.