-

April 1967

Volume18Issue3

As President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant was not nearly so good at picking assistants as he had been when he was a general: his Cabinet, with few exceptions, was far from illustrious. Among Grant’s worst appointments was George S. Boutwell, Secretary of the Treasury. He came to office at a time — 1869 — when the nation badly needed reforms in currency, taxation, and tariff policies; but “the one idea that flowered in his Sahara mind,” historian Allan Nevins remarks, “was the reduction of the national debt.”

One way to reduce the national debt, Boutwell figured, was to cut down on expenses and waste, starting with his own department. He took a tour through the Treasury Building, and announced that he had discovered the source of a serious leak in United States funds: there were too many female clerks employed by the Treasury Department, and most of them were not earning their keep. These excess persons, he decreed, would have to go — forthwith. And go they did.

While this move was regarded with consternation by the nation’s feminists, to whom it was a serious setback in the struggle to improve the lot of the working girl, it struck the weekly magazines as quite amusing. Most of them were inclined to think, anyway, that woman’s place was in the home, preferably a home where a number of weeklies were delivered regularly.

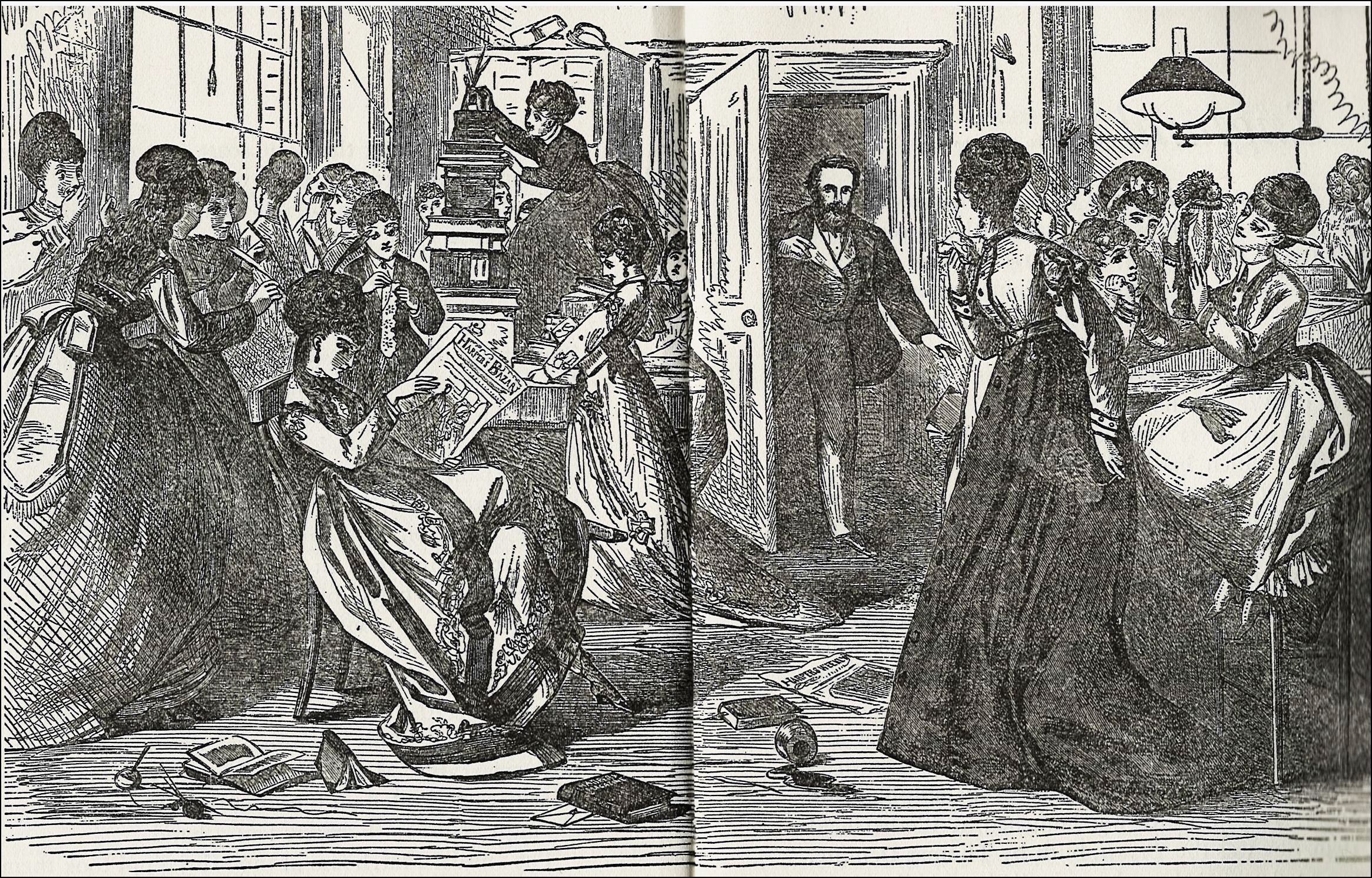

Two of the weeklies — Harper’s Bazar and The Day’s Doings — reacted to Mr. Boutwell’s economy measure. The Bazar’s satirical engraving represented the moment when, supposedly, the new Secretary comes through the door into a room full of lady clerks who are engaged in such nonfiscal pursuits as decorating hats, playing practical jokes, using the ledger books as building blocks, and studying the latest fashions (in the Bazar, of course). One of them, who has moved on from folly to vice, is smoking a cigarette.

The Day’s Doings provided the sequel: the departure of the clerks after the Secretary has issued his stern command. It is an interesting insight into the journalism of the period that whereas in Harper’s Bazar the girls all appear to be rather elegant young ladies, in The Day’s Doings — a salty New York publication that usually specialized in sex and crime stories—they look like trollops.

One of the magazine’s reporters wrote an accompanying story in the sharp style to which his readers had become accustomed:

The female element of the Treasury Department, at Washington, has come to grief, for a number of the fair employees of that department have received their congé. Fate is inexorable, and the hearts of our great officials are hard as stone. If tears could have melted them, if expostulations could have any effect upon them, if talk could have changed their purposes, if the light that lies in woman’s eyes could have pierced into the official darkness of their souls, not a female Treasury clerk would ever have been dismissed, for it may readily be imagined that none of these were spared in behalf of the now placeless placewomen. But the fiat had gone forth, and there were none to save them; congressmen were invoked, even the President himself was importuned, but a just economy and the public weal overwhelm all personal or individual considerations; and so the Treasury girls departed, not as did the children of Israel from the land of Egypt among the walled-up waters of the Red Sea, but “more in sorrow than in anger” amidst the lamentations of their friends and would-have-been protectors [congressmen], who stood about the steps of the Treasury Building, as their fair ones, each with her little luggage, stepped forth from the gloomy pile which was to contain their beauties and witness their labors no more forever. Some of the dismissed dear ones left majestically, others wended their way mournfully, while not a few forgot their troubles in their native coquetry. It was, indeed, a touching spectacle for the male congressional heart; and the male congressional heart, in consequence, throbbed convulsively, and the male congressional eye was suffused in unofficial tears.…

The male congressional eye might as well have remained dry. Behind the marching legions of feminism the female clerks have returned to the Treasury Department not in hundreds but in thousands, while George S. Boutwell has been profoundly forgotten.

These days, though, if any of them are idle on the job, it’s probably less a matter of goldbricking — Franklin D. Roosevelt put an end to that in 1933 — than one of the doubtful benefits of the Computer Era.