We weren't always welcomed home from the war. But we were good at what we did and the patients knew we mattered.

-

November/December 2024

Volume69Issue5

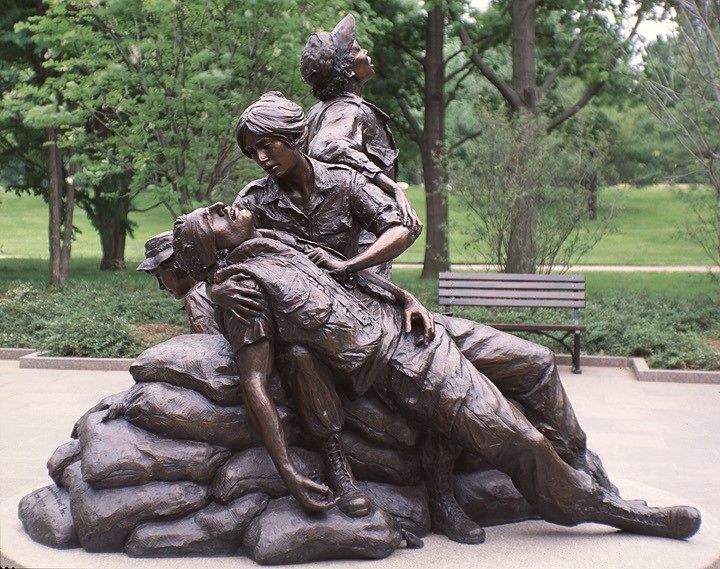

Editor’s Note: Capt. Diane Carlson Evans served in the Army Nurse Corps in 1968 and 1969 in Vũng Tàu and Pleiku provinces, and is the author of Healing Wounds: A Vietnam War Combat Nurse’s 10-Year Fight to Win Women a Place of Honor in Washington, DC. She is founder and president of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Foundation, and has received many honors for her long, difficult campaign to create the memorial to the 11,000 military and civilian women who served in Vietnam and the 265,000 who served around the world during the Vietnam era. All photographs courtesy of the author unless otherwise credited.

My plane touched down in Vietnam on August 2, 1968. The blast of heat and the smell of jet fuel and sewage hit me first, then the sight of GIs with M16s and bandoliers of ammunition slung across their strapping chests.

Three days later, after trading my skirt and heels for jungle fatigues and combat boots, I choppered to my ultimate destination, the 36th Evacuation Hospital in Vũng Tàu, a 400-bed evacuation hospital providing care to patients evac’ed from other in-country hospitals and casualties directly out of the field.

Once a French colonial town called Cap Saint-Jacques, Vũng Tàu was a seaside resort town with a backdrop of small mountains about seventy-seven miles east of Saigon. As the door gunner locked his eyes on the ground, I noticed the red crosses signifying U.S. military hospitals. Even if the Viet Cong weren’t great respecters of the off-limits status of hospitals featuring such designations, Vũng Tàu was considered one of the safer hospital locations relative to the 23 or so other U.S. Army medical outposts in Vietnam. White surf folded on nearby beaches that hemmed the South China Sea. Soldiers on R&R swam, drank beer, and tossed footballs back and forth.

That said, you quickly learned that even the relatively heavenly places in Vietnam could be tinted with a certain hell. On my first day in the sixty-bed unit the inside temperature was 105 degrees with no air conditioning, not even on the burn ward. Only the OR, ICU, and Recovery Room had this luxury. Huge floor fans chased around the fetid air. For me it didn’t matter, but it did for wounded GIs whose suffering was greatly compounded by the heat. They deserved better.

I was used to seeing trauma in Minnesota. But there it was explicable: farm mishaps, auto accidents, drownings, and homicides. In Vietnam, I was overwhelmed by the hundreds of our young soldiers, Vietnamese, and Montagnard civilians who wound up here for one of myriad medical or surgical reasons: bullets, shrapnel, booby-trapped grenades tripped by wires and fragmentation mines detonated by enemy guerrillas, Bouncing Betty mines, snake bites, punji-stick wounds, helicopter and vehicular crashes, leeches, fevers, water buffalo attacks, monkey bites, burns, malaria, dysentery, and dozens of diseases we’d never heard of before we arrived.

Half of all deaths of U.S. soldiers would come from small-arms fire, a third from artillery, and a tenth from booby traps, among others.

Vietnam during wartime, I soon found, was a dirty place – which complicated our medical care. North Vietnamese forces invented cheap, clever ways to immobilize our troops with lethal homemade booby traps. They would lace punji sticks with human feces so that when a U.S. soldier stepped on it, he would suffer debilitating pain and guaranteed infection.

Most wounds required DPCs – delayed primary closures. Our skilled medics irrigated the wound and packed it with fresh dressings daily. On the third day, the surgeons could close the wound. Meanwhile, the soldier would be given tons of antibiotics. When the wound was sufficiently healed, we nurses and medics would remove the sutures and the soldier would go back to his unit – or home, if the injury was bad enough.

We nurses and medics were from all parts of the U.S. Most of us were between twenty-one and twenty-five. I was twenty-one, slightly older than the average age of the soldiers themselves, who were about seven years younger than the average U.S. soldier in World War II.

Almost a third of our nurses were male. We reflected the fabric of our society at the time: mainly Caucasian, but also Native American, African-American, Asian-American, Hispanic, and Jewish. We had a few gay male nurses and a few lesbian nurses, but those preferences were far more secretive than they would be today. They had to be. If discovered, they were discharged, and their military career ruined. Many of them were my friends; they were outstanding nurses.

Although there had been talk the previous year about nurses at Vũng Tàu wearing white dress uniforms, mainly to inspire morale and paint the stereotype of a true nurse (female, no less), that idea was blessedly nixed. We wore what was practical in Vietnam: lightweight jungle fatigues, which protected the arms and legs from mosquito bites, and didn’t require the laundry attention whites would in such a dirty place. Above all, they didn’t require the awful constriction of a belted waist and those dreadful nylon stockings.

The wounded soldiers we saw at Vũng Tàu were with us between a few days and a couple of weeks or more. For all the horror involved, the reality was that if a wounded soldier could just get on a helicopter and then to a hospital within an hour, he had a ninety-eight percent chance of surviving. The next few hours in the ER and OR often determined whether he stayed in Vietnam or was handed off to Air Force flight nurses and personnel for the trip along the air-evac chain to determine the next best place for recovery.

I was assigned to a surgical unit, all pre-op and post-op. I did my share of nights but preferred the day shift, when I could interact more with the patients.

We sometimes ate dinner downtown in the village. I recall four male sergeants unexpectedly giving us female nurses leis to wear around our necks and pink champagne. They snapped photos of us eating together. They walked out, handed us the Polaroid, and paid the bill for the whole thing. Two MPs (Military Police) followed us until we were safely back to our billets.

Because we also took care of the local Vietnamese, we nurses saw things we’d never been trained to treat. On Christmas Eve 1968, I was working a burn unit when some fifty children were admitted after being seared by napalm when their village was bombed.

I cared for these innocent children, blackened by man’s inhumanity to man. The juxtaposition of innocence and horror was like nothing I’d ever seen; most were crying for parents who were dead, wounded, or searching frantically for their missing child miles and miles away.

Napalm, a jellied-fuel firebomb mixture, sticks to its target when ignited. And even if people weren’t the intended target, it burned them deep down to the bone. Like a lot of wounds in Vietnam, I’d never seen anything like it before; we were inadequately prepared for what we were going to face. But there wasn’t time to bemoan that; instead, we simply figured out what to do on the fly and from each other. Doctors gave the orders and we followed them.

We got the children into beds, some two to a bed – the unit was overflowing – and started IVs on those we could. For days, we applied topical Sulfamylon on the burn area, which would help prevent a pseudomonas infection, and later debrided the necrotic tissue. Our physical therapists worked their magic with whirlpool baths. For us, it was tedious work with slow progress; for the children, endless days of excruciating pain.

Was it that night, seeing a ward full of burned children, when I stopped being the idealistic farm girl from Buffalo, Minnesota?

Or was it the agonizing ritual of placing the white sheets over faces of dead young men before they’d be put in black body bags, then flag-draped coffins and shipped home to mothers and fathers?

In Vietnam, it was impossible to prepare for the sinister threats about to destroy the bloom of our youth. It happened gradually. And though I clung to whatever soul I still had left, I was discovering that the carnage threatened to suck the life, hope, and dignity out of each one of us – if not now, then when we got home.

The weirdness of Vietnam was that even the silver linings had hidden clouds. You could walk the beautiful beaches of the South China Sea, sure, but did you ever feel as safe as you might back home? No. You could stroll the villages of friendly Vietnamese holding their endearing children, yes, but in a time of war, did you ever trust them or feel totally safe? No.

As my time in Vietnam continued, I saw the best of America in our hospital beds while working side by side with hundreds of our brave men and women. Fate chose this battleground for my generation. It did not distinguish between combatants and noncombatants or innocent children. Our fate, I was starting to realize, was being determined by the stroke of a pen by senators and congressmen in Washington, D.C., most of them who knew nothing of war.

Our civic action program was ostensibly designed to “win the hearts and minds” of the people whose freedom we were there to defend. Docs, medics, and nurses would go into the villages or orphanages with supplies to treat a variety of illnesses. We set up temporary field clinics to provide dental and medical treatment to the local population. The South Vietnamese civilians seemed to appreciate our visits and were fascinated by our presence.

I did this on my days off from the 36th Evacuation Hospital, falling in love with the sweet little kids. But while relief from a toothache and removing parasites helped them immensely, we continued to bomb their villages and inadvertently kill their innocent families, creating a hypocritical monster in the process that couldn’t be ignored. Those villages harbored the enemy, the Viet Cong. And the VC were killing and torturing our men.

In a perfect world, there would be no war. In a perfect world, the combat theater could separate the enemy from the innocent. But the lines between perfect and imperfect were blurred badly in Vietnam; like it or not, our job was to clean up the mess left by our government’s decisions.

Both sides played the game. The U.S. paid our “mama sans,” South Vietnamese women, to scrub floors in the hospital wards, to do our laundry, to help free us up so we could devote ourselves to our jobs as nurses. Meanwhile, though, in their own economic desperation, some stole our underwear, bras, perfume, and clothing. Because they had access in the hospital areas to clean, it was not uncommon for us to learn of stolen drugs, at times stuffed up the women’s vaginas to avoid detection. IV bottles and surgical supplies also sometimes went missing.

Eddie Lee Evenson is the only patient whose name I remember. Eddie was from Thief River Falls, Minnesota. Angular and strong with a ready smile, he endeared himself to the corpsmen and nurses. He came into the 36th with relatively minor injuries; after being loaded with antibiotics and a delayed primary closure of his wounds, he had his sutures removed and was sent back to his infantry unit. In the meantime, helping us out relieved his high energy and boredom.

No job was too small for Eddie. He was sweet and respectful, and felt like a brother to me. When he went back to the field, he made me promise to write to him. We exchanged a few letters.

I was transferred to the 71st Evacuation Hospital in Pleiku. It was there that the manila envelope arrived. Eddie was dead. No. Eddie was too good to die. But the letter I sent him had not been opened. The commanding officer sending me this news said the letter was found on his body.

Mail call was a precious time. He hadn’t opened his mail yet. Like the rest of us, I knew he’d wait for the right time to open a letter and savor the words inside. I vowed to myself that I’d never get another message like this; I would never get as close to another soldier.

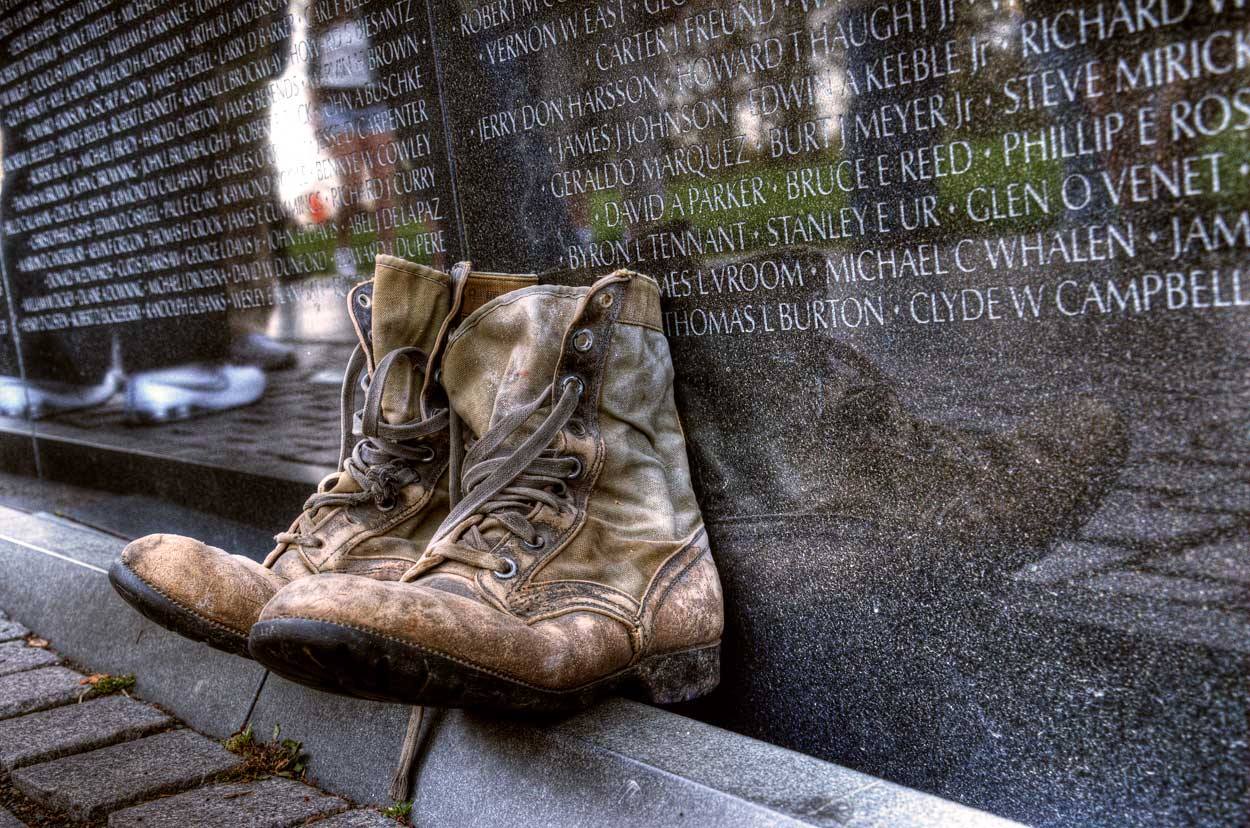

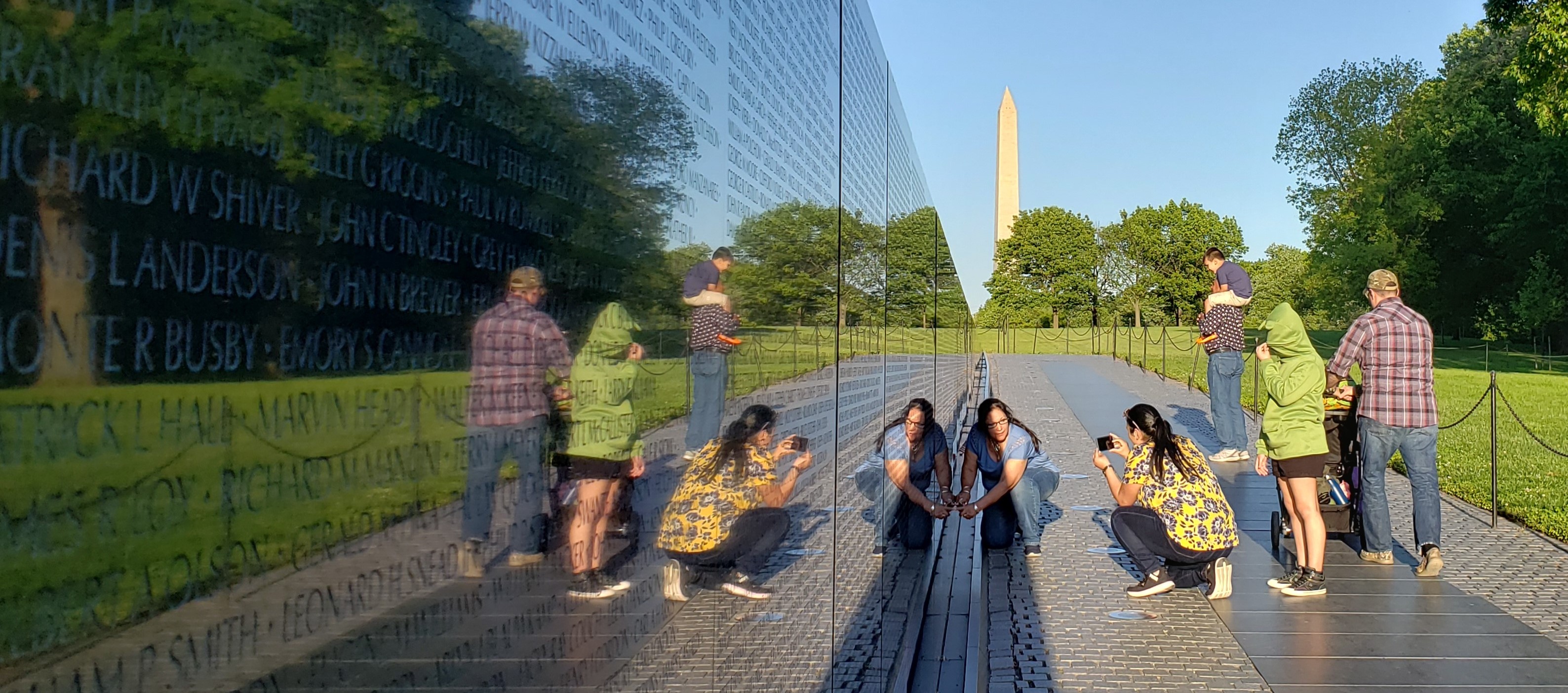

Years later I made my first visit to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on November 11, 1982 – the dedication of The Wall. It was an autumn morning in Washington, D.C. Though people surrounded me, I felt alone. If there was sound, I was not hearing it. If there was a feeling to this place, I was not experiencing it. Not yet. I was numb.

Read about the long and challenging campaign to build the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in “To Heal a Nation: Creating the Vietnam Wall” in the June 2021 issue of American Heritage

Ahead waited The Wall of black granite – carved with the names of more than 58,000 souls. Though I knew that it was The Wall that had summoned me to this place, I still denied its power and meaning.

I stopped when the granite plates loomed before me, but still I couldn’t look up. Instead I gazed down at the sandals, tennis shoes, penny loafers, flats, and boots on the people moving around me. I focused on the combat boots. I felt dizzy. Did I know the man in those boots? How about the one to my left? To my right? Are any of them the patients who still live in my mind?

I wonder now about my own black leather combat boots. They must still be in the attic on the farm. My husband and children had never seen my uniform or boots, my medals, my photographs. My boots, if they still existed, would probably be caked with red dirt from the Pleiku highlands, still stained with my last patient’s blood. I wanted to look at them, hold them, and confirm that I actually wore them.

I brought one thing with me to D.C.: my boonie hat, with patches from the 44th Medical Brigade, 71st Evacuation Hospital. I pushed it back on my forehead a little as I finally looked up at The Wall, and found the names I came for – Eddie Lee Evenson, Panel 28 W, Line 17, and Sharon Lane, Panel 23W, Line 112.

As I touched Eddie’s name, a man wearing a tattered, faded field jacket gently placed his hand on my shoulder.

“Were you a nurse in Vietnam?”

“Yes,” I admitted.

“I’ve waited 14 years to say this to a nurse,” he continued. His voice wavered, and tears pooled in his eyes. “Thank you. I can never thank you enough. I love you. Thank you for being there.” These simple words were the most profound words that I will ever remember. They were precious words, to him and to me. This wounded soldier had survived and he was grateful.

I felt something break inside of me. For the first time since Vietnam, I cried. I had been terrified of crying, afraid that once I started I wouldn’t stop. Behind the tears was anger at the injustice, the futility, and the betrayals of war.

I finally touched Eddie’s name as he had touched my life the day he was wounded. And my fellow Army nurse Sharon Lane’s. She was killed in Chu Lai on June 8, 1969, while I went about my duties in Pleiku.

The Vietnam veteran who embraced me that day near The Wall may never know that his act of love pressed me to embrace my own past. My life would never be the same again. I must have lived for a reason. There was something yet that I had to do with my life. In a spiritual and mysterious moment, Eddie and Sharon gave me permission to live, to feel, show emotion, and see again the faces of war.

My visit to the Wall stirred something deep within me. Soon thereafter, the soldiers from my wards started appearing at night in my dreams, more frequently than usual. I’m covering the face – or what’s left of that face – of a twenty-two-year-old chopper pilot with a sheet. I’m opening the door to a ward full of South Vietnamese kids who’ve been seared by napalm. I’m leaving a young soldier – my year in Vietnam is over – who pleads for me to stay.

My life started unraveling. Many nights I was back in Vietnam, but I couldn’t grab my helmet and get to work. I’d wake with a jolt, trying to run to my ward, only to realize I was in my own bed, my legs frozen in place next to my husband Mike’s. My heart raced with the adrenaline I had grown addicted to. Now it was working adversely; I was shaking, sweating, and agitated. As it had been in Vietnam, my sleep was fitful. I was always half-ready for the next chopper to drop in with its load of wounded. I was exhausted. Depressed.

If my visit to the Wall had loosened my emotions, it hadn’t fixed anything. In remodeling-speak, it was the tear-down before the re-build. My default format was still, “Tell nobody. Feel nothing. Risk nothing.”

Finally, I went to a Vet Center in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Therapy didn’t come easily for me. But I was appreciatively surprised at the warm welcome I got. My counselor, a wounded combat vet, was frank with me.

“Diane, the only way you can heal is to face the past,” he said. “You’re going to have to think about it, write about it, talk about it.”

In late January 1983, a couple of months after the Wall dedication, we were at Mom and Dad’s in Buffalo, Minnesota, in the 1868 farmhouse where I’d grown up. Mike and our four children were off sledding and riding snowmobiles. As was our habit, my mother and I sipped our coffee and glanced out the window where several feet of snow lined the fallowed fields.

“Diane,” she said, “perhaps it’s time for you to go up in the attic and get your stuff.”

“My stuff?”

“Your footlocker. Your duffel bag. The things you brought back from –”

“Mom, you saved that all these years? Why?”

“It’s yours. It’s part of you. And you told me to save it for you. You sent it with explicit instructions, ‘DO NOT OPEN.’ I haven’t. But maybe you should.”

Once in the attic, I looked at the scuffed olive-green footlocker. Wood handles, left and right. My name stenciled in faded black on the lower front – “Carlson’’ – with my Army Nurse Corps number. When I lifted the lid, I knew I wasn’t just opening a footlocker. I was opening Pandora’s Box. The Wall was ours, a memorial to our war dead. The footlocker was mine, a memento of my personal war.

There was my stethoscope. Two bandage scissors, one large and one small. A rubber tourniquet. All were still hanging in the buttonholes of my jungle fatigue blouse. Two black U.S. government-issued pens in the shoulder pocket. Unit patches gifted to me from patients: 1st Cavalry Division, 1st Infantry Division, 101st Airborne Division, and many others. A Dustoff unit patch. A Viet Cong flag that a patient insisted I have. A rabbit’s foot, the good-luck charm of a soldier for whom it had not been. And a copper peace symbol I’d worn around my neck on a leather shoelace, given to me by a medic who’d made it for me. I tried to see him now; what did he look like? Why can’t I remember him? A Green Beret. Yes, I remembered the face of the confident U.S. Army Special Forces lieutenant who had given this to me as he limped out of the hospital and back to his unit in the Central Highlands.

I opened a box that said “DO NOT OPEN” in my own handwriting, sent from Vũng Tàu. I found the Saint Christopher medal given to me by a West Point lieutenant who got the million-dollar wound and left for home. I felt his hand reaching out to me now, giving it to me as I helped him roll over onto the gurney for his evac out, taking the medal off his neck and hearing him say, “Put it on, ma’am, wear it. It will keep you safe.”

Finally, I saw them: my boots. Still coated with the reddish-orange dust of Pleiku and the splatters of soldiers’ blood. I turned them over and gaped at their soles. They were worn thin with large holes. I hadn’t noticed that in Vietnam. How could I have walked in those? Why hadn’t I requested a replacement? They were my second skin. I’d lived in them every day.

I closed my eyes and smelled the monsoon rain, my moldy room, burned flesh, jungle rot, and pseudomonas. I had no recollection of good smells in Vietnam beyond coffee, the cinnamon rolls I made, and the perfume some of us wore.

It’s true. I’d really been there.

Then came a thought that I hadn’t expected: I missed Vietnam.

Despite so much tragedy, there were elements that I genuinely missed. I missed the GIs, the intensity of every day, every minute. I missed the adrenaline. I missed my medics and my patients and getting up every day to go to work to do something worthwhile. I missed being valued, being someone important to hundreds of lives. I missed the rush. The thinking on your feet. The responsibility. The risk. The doing something few could do, as if part of a secret, if dark, world.

Maybe I should talk to somebody to process this. But who could possibly understand the apocalypse that Vietnam was, the dichotomy Vietnam was?

It was the best year of my life. It was the worst year of my life. I wanted it all back and I didn’t want any part of it. I missed my hootch-mates, the women who lived with me in our compact wood-built quarters. I missed the docs and medics, and my ward masters. I missed the noisy skies filled with assault helicopters, the Dustoffs – choppers that plucked the wounded from the ground – and supply planes. I missed seeing the convoys of mud-crusted, sweating GIs. I missed the daring chopper pilots we loved. I missed defying orders by the “lifers” – some of the high-ranking officers we loathed. I never turned down the offer to fly in a chopper or plane – and not caring that I wasn’t on approved orders because, as we joked, what could they do to us – send us to Vietnam?

We were defiant, we became good at what we did. No, great at what we did.

The country didn’t welcome us home, but our patients knew that we mattered.