Michael Corcoran led New York’s Irish brigade to glory in the Civil War after being disciplined for refusing to parade in honor of Britain's Prince of Wales.

-

November/December 2024

Volume69Issue5

It was the biggest event in recent memory for New York City, and the “metropolis of the New World” outdid itself to honor the Prince of Wales, Queen Victoria’s oldest son, in the first visit to America by a member of the British royal family.

On October 11, 1860, more than 200,000 people turned out on a splendid autumn afternoon in Manhattan for a parade in the prince’s honor, turning Broadway into what one observer called “one vast trough of humanity, animated, glittering, good-natured, and bent on making the best of all possible greetings to the coming Prince.” Union Jacks fluttered, and bands played “God Save the Queen.” New York militia regiments marched in review before the prince. As each unit passed, its commander saluted the future King of England.

Only one thing was missing. Colonel Michael Corcoran and the New York militia’s 69th Regiment had defied orders and refused to march. Most of the men in that regiment, including Corcoran, had been born in Ireland. They were strident Irish nationalists and steadfast foes of the British monarchy. Corcoran believed that he could not in good conscience order these Irish-born soldiers to march in honor of the son of “a sovereign under whose reign Ireland was made a desert and her sons forced into exile.”

There would be consequences for this defiance, and it would be only the start of the controversies that would shadow Corcoran for the rest of his military career.

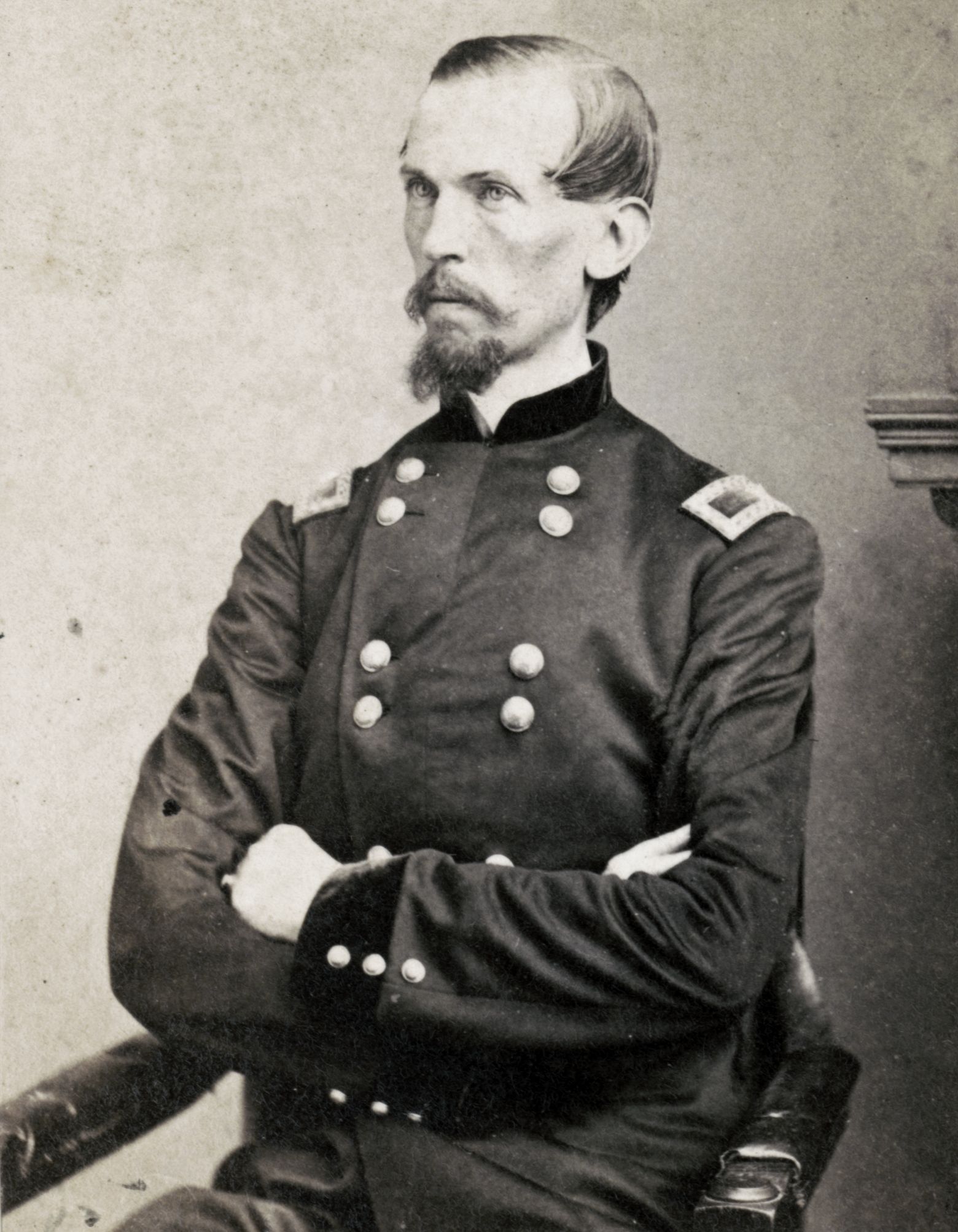

Born in County Sligo, Ireland, in 1827, Corcoran was the son of a former British Army officer. In 1846, he joined the country’s police force, the Royal Irish Constabulary. Ireland was in the grips of a famine that killed more than a million people and drove thousands more to emigrate to America. While on duty in County Donegal, Corcoran saw depots packed with cattle and grain. These provisions could have helped feed his starving countrymen, but the British had reserved them for shipment to England.

This radicalized Corcoran, and he left the constabulary to join the Ribbonmen, a secret society that terrorized British landlords. His activities caught the attention of the authorities, and he fled to America in 1849, one step ahead of the constable.

Like the more than 150,000 other Irish who came to the United States that year, Corcoran sought opportunity, and America, he later wrote, “gave me all the opportunities I longed so for.” He found work at Manhattan’s Hibernian Hall, a tavern and gathering spot for Irish immigrants. He became active in Tammany Hall politics and in the Fenian Brotherhood, a group dedicated to freeing Ireland from British rule.

In 1851, Corcoran enlisted as a private in the New York militia’s 69th Regiment. Standing 6 foot 2 and weighing 180 pounds, Corcoran was a natural leader, rising quickly through the ranks. In 1859, his men elected him colonel, and he became regimental commander.

Corcoran’s defiant boycott of the parade was anything but a secret. “The Sixty-ninth (Irish) Regiment did not parade,” noted a front-page story in the next day’s New York Times. A week earlier, the press had reported that the regiment had voted to snub the parade, refusing “to exhibit ourselves before the Lord Prince of Wales on the 11th inst., or at any other time,” and that Corcoran had warned his division commander, Major General Charles W. Sandford, that he planned to ignore Sandford’s order to march in honor of the prince. On November 14, 1860, court-martial charges were filed against Corcoran. If convicted, he faced the loss of his commission or dismissal from the militia.

The case became a cause célèbre, drawing attention across the United States and from both sides of the Atlantic. To some, Corcoran’s actions showed that Irish immigrants were untrustworthy, loyal to their native land but not to their adopted homeland. At the very least, Corcoran and his men should be sent “somewhere to learn good manners,” the New York Herald suggested.

To others, he was a hero, acting “lawfully as a citizen, courageously as a soldier, indignantly as an Irishman,” said Thomas Francis Meagher, Corcoran’s militia colleague and fellow Fenian who was later promoted to brigadier general in the Union army.

Corcoran’s court-martial trial began on December 20, 1860 at the Division Armory before three judges: Brigadier General Charles B. Spicer and colonels S.B. Postley and Joseph C. Pinckney. The room was packed, mostly with Corcoran’s supporters.

The case seemed clear-cut. Sandford had ordered the 69th Regiment to march in honor of the prince, Captain Henry S. Van Buren had hand-delivered Sandford’s order to Corcoran, and Brigadier General John Ewen had given Corcoran a written reminder two days before the parade. Nevertheless, Corcoran didn’t march and had refused to order his men to march.

With the facts so firmly against him, Corcoran raised a technical defense. He argued that New York law prohibited militia units from being required to march in more than two parades per year. Since the 69th Regiment had already marched twice before October 11th, he claimed, Sandford’s order was a nullity.

The prosecutor countered that as division commander, Sandford had the inherent authority to order militia units to take part in more than two parades. The trial ended on April 8, 1861, and a decision was expected two weeks later.

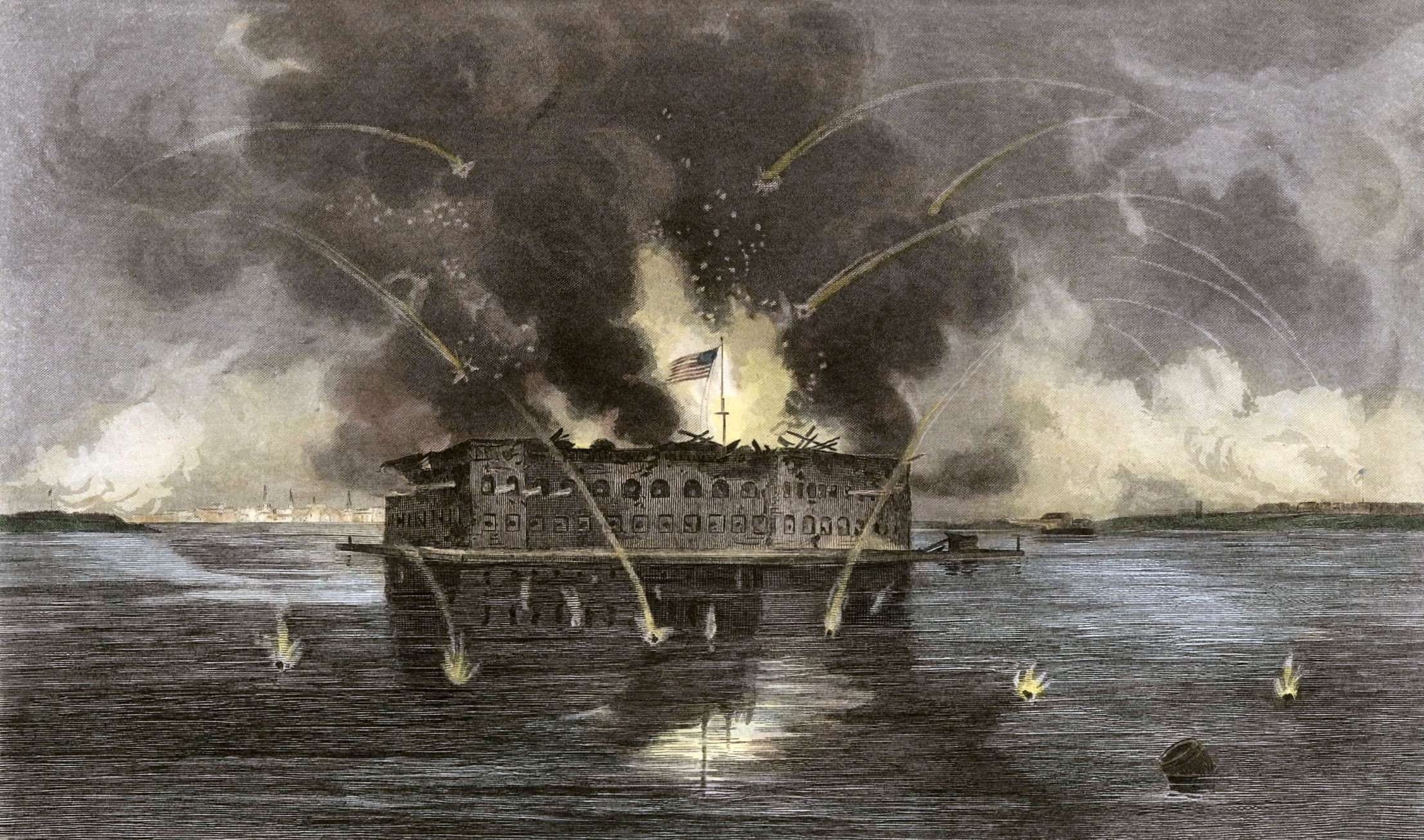

That decision will never be known because on April 12, 1861, fate intervened when the Confederacy attacked Fort Sumter. Three days later, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to quell the rebellion. The New York militia desperately needed men, and because of his popularity in New York’s Irish-American community, Corcoran could supply them. On April 20th, Sandford dismissed the charges and reinstated Corcoran as regimental commander.

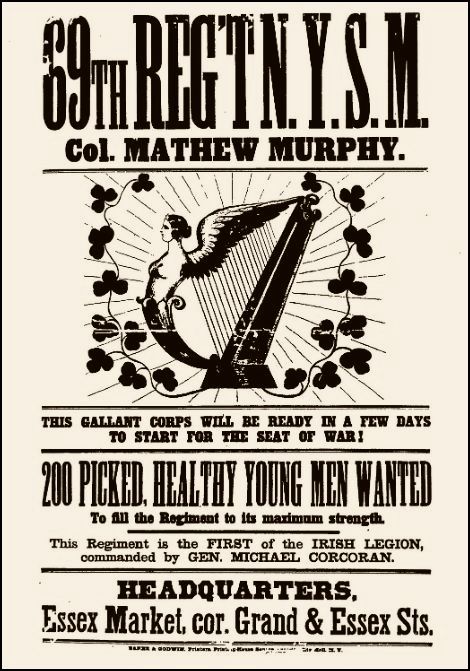

With an authorized strength of 1,000, the 69th Regiment needed to quadruple its ranks from its current roster of 245. Corcoran quickly went to work, turning Hibernian Hall into a recruiting station. “Young Irishmen to Arms!” blared the recruiting posters. Outside the hall, three times the number of men needed lined up to enlist. On April 23, 1861, the 69th Regiment, now at full strength, marched down Broadway to board a ship to Washington, D.C., where they quartered in Georgetown.

By the end of the war, more than 150,000 Irish-Americans will have fought for the Union and more than 20,000 had joined the Confederate Army.

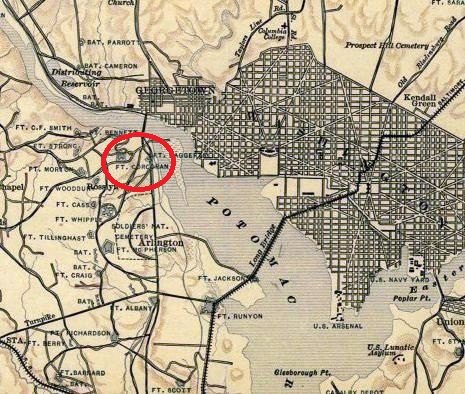

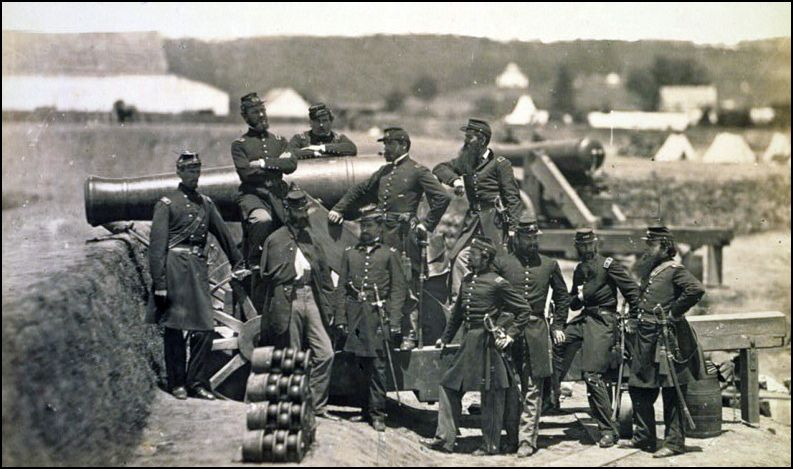

On May 23, Virginia voters ratified the Ordinance of Secession that took their commonwealth out of the Union. Within hours, Corcoran and his men marched across the Aqueduct Bridge to help seize areas of northern Virginia around the Capital. They began construction of Fort Corcoran on the heights above the bridge, from where they could look down on Washington and control access across the Potomac.

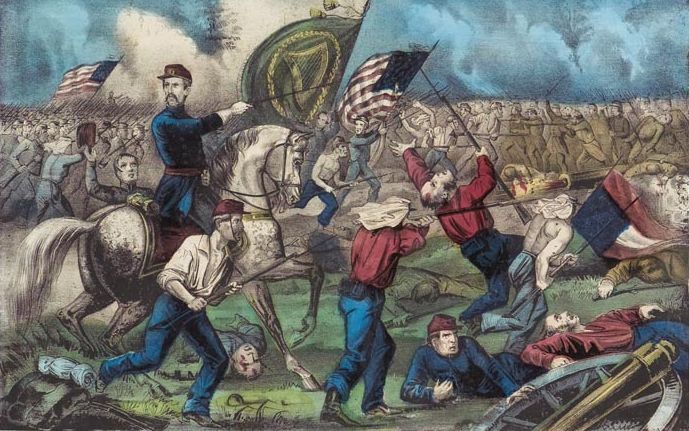

Two months later, Corcoran and his men got their baptism of fire when Union troops under Brigadier General Irvin McDowell met Confederate forces near Manassas, Virginia, and a creek called Bull Run. It was the first major battle of the war, and Washington society – men in top hats and women in bonnets with picnic lunches and bottles of champagne – rode their carriages out to Manassas, expecting to watch the rebels get their comeuppance. Instead, they saw a Union defeat and federal troops fleeing the field in panic.

The 69th Regiment joined the fighting near Henry House hill at Manassas. Twice, it attacked the Confederate position on the hill, and twice it was repelled. “Colonel Corcoran was everywhere conspicuous, cheering on and rallying the troops,” Captain D.P. Conyngham recalled. As other Union troops began to withdraw in disorder, Corcoran’s men tried to hold their ground, but “(t)he panic was too general, and the Sixty-ninth had to retreat with the great mass of the Federals,” the regiment’s after-action report stated.

As the withdrawal turned into a rout, Corcoran tried to reorganize his men. On foot because his horse had been shot from under him, he grabbed a flag and ordered his men to rally to him, but in the noise and confusion, only 11 did so, and the Confederates quickly captured this small band. It was a costly day for the regiment, with 41 killed, 88 wounded and 65 taken prisoner.

Corcoran was transported to Richmond and confined with several hundred other Union prisoners in a tobacco warehouse. “(L)anguishing in the dungeons of your country’s enemy, almost within hearing of the booming guns of the struggling armies, is a most awful fate,” Corcoran wrote.

Confident in ultimate Union victory, however, he taunted his captors, telling them, “Your turn now; our turn next.” The Confederates offered to release him on parole, but that would have required him to agree not to take up arms against the Confederacy. As a matter of honor and patriotism, he said, he could make no such promise.

On September 10, 1861,54 Corcoran and more than 100 other prisoners were sent south to Castle Pinckney, a fort on an island off Charleston, S.C., and his situation soon took a dramatic turn for the worse.

Earlier in 1861, the Confederate government had authorized civilian ships, called privateers, to seize Union merchant vessels. Because the Union did not recognize the legitimacy of the Confederate government, it treated captured privateer crewmen as criminals, not combatants. In October 1861, it formally charged more than a dozen of them with piracy, a capital offense. On November 9, 1861, the Confederate government retaliated, choosing 14 Union prisoners by lot as hostages for the privateer crewmen. If the crewmen were executed, the hostages would suffer the same fate. Corcoran was one of the 14 whose names were picked.

As a hostage, Corcoran was held in solitary confinement in an unheated 6-by-8 felon’s cell in a Charleston jail, but he remained defiant. If his captors “imagine that their cruelty or inhumanity can make me falter…,” he wrote, “they are sadly mistaken.” An attack of typhoid fever added to his miseries.

The stand-off ended in February 1862, when the Lincoln administration agreed to treat privateer crewmen as prisoners of war, and Corcoran reverted to prisoner status. He was soon moved again, this time to Columbia, S.C., with a group of prisoners “deemed dangerous characters – quite complimentary to me,” he wrote.

He was freed on August 15, 1862 in a prisoner exchange, swapped for a Confederate colonel, Roger W. Hanson. By this time, Corcoran’s exploits had made him a national celebrity, and his trip home to New York became a major event in each city he passed through.

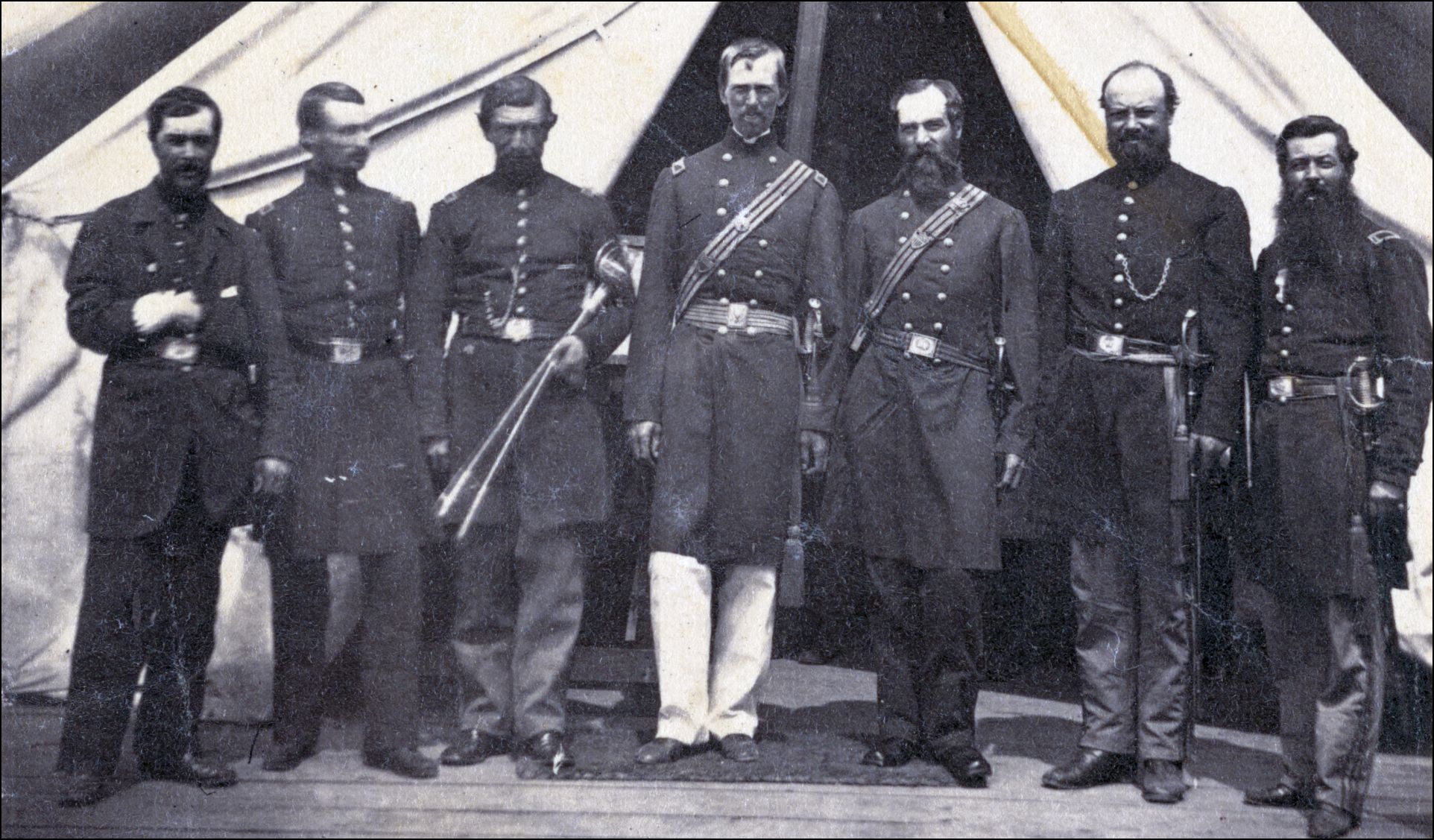

In Washington, D.C., the carriage taking him from the train depot to his hotel was “surrounded by a dense throng and three deafening cheers rent the air, given with a hearty good will and an earnest feeling seldom exhibited,” a reporter noted. The next day, he was promoted to brigadier general, and along with three other recently repatriated officers, he dined at the White House with Lincoln and General in Chief Henry Halleck. Enthusiastic crowds greeted him when he passed through Philadelphia and the New Jersey towns of New Brunswick, Newark and Jersey City.

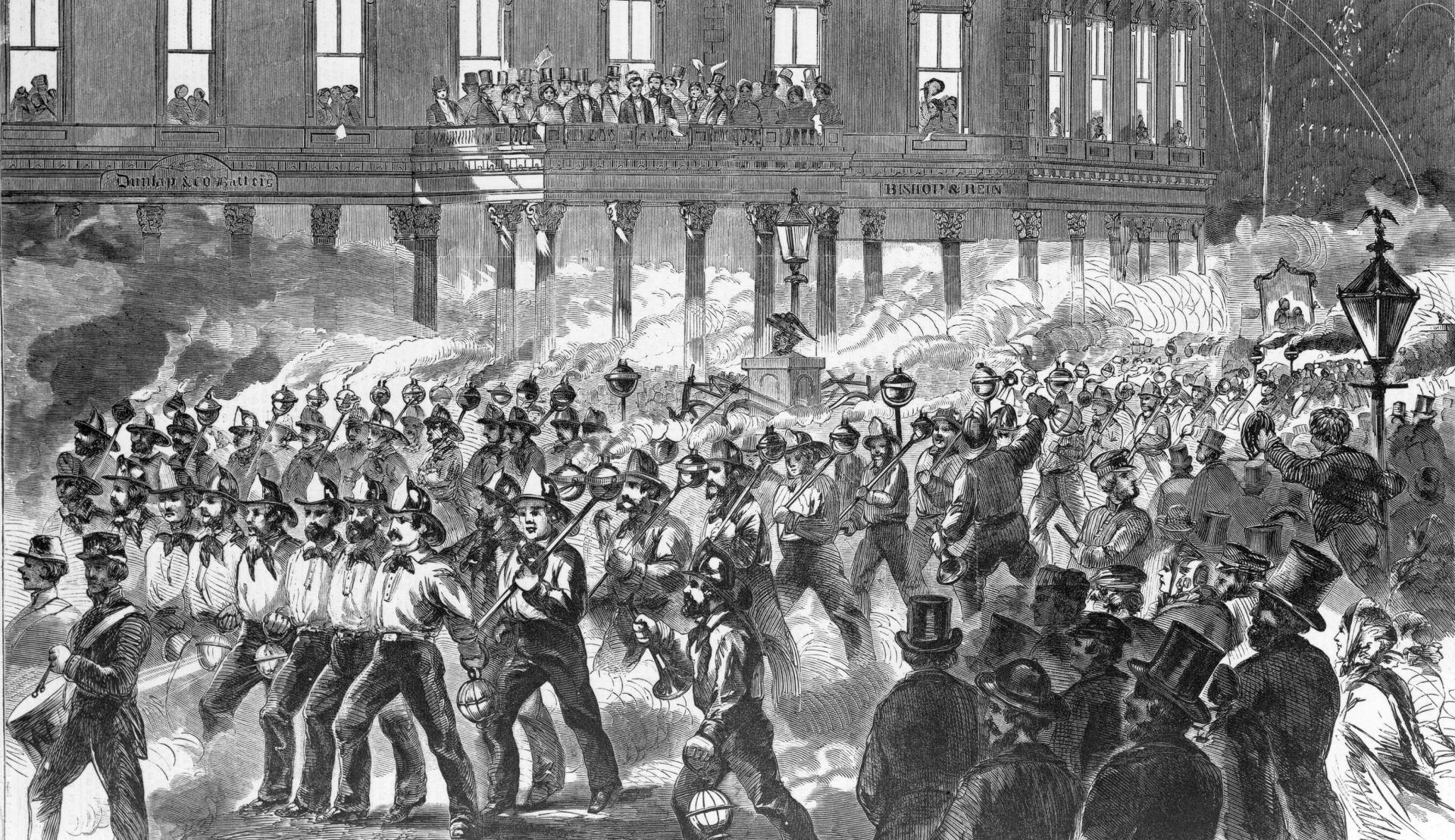

The grandest reception of all took place in Corcoran’s adopted hometown. On August 22, 1862, New York City held a gala parade to honor him, an event Harper’s Weekly called “one of the most brilliant ovations which New York ever gave.” Exuberant onlookers jammed the parade route and mobbed Corcoran’s carriage as it proceeded down Broadway. “(O)n no previous occasion has the City of New York tendered to an individual, be he President or Prince, such an apparently heartfelt ovation…” said one observer.

The irony was inescapable. Corcoran had “now grown so famous as to enforce a popular homage here which himself had been foremost to deny to a Prince of purest blood and of the Royal line,” the New York Times noted.

Because Corcoran was released in a prisoner exchange, not on parole, he was free to re-enter the war, and he prophetically vowed to fight “until victory perches upon the National Banner of America, or Michael Corcoran is numbered among those who return not from the battle-field.” He recruited a new brigade, called Corcoran’s Legion, and men flocked to Manhattan from as far away as Boston and Philadelphia to serve under him. Within six weeks, he had recruited six regiments. On November 11, 1862, his brigade sailed south for duty near Suffolk, Virginia.

The Corcoran Legion saw its first action on January 30, 1863, when it routed a Confederate force at a place called Deserted House, about 10 miles from Suffolk. Major General John J. Peck commended Corcoran’s men for their “good conduct and gallant bearing” and “patriotism worthy of imitation.” That same year, the legion took part in several other campaigns in Virginia.

Corcoran was soon ensnared in a new controversy. Shortly after 2 a.m. on April 12, 1863, he left his headquarters near Suffolk to inspect his lines when Lieutenant Colonel Edgar A. Kimball of the New York militia’s Ninth Regiment halted him and demanded the password. Corcoran identified himself and asked to be allowed to proceed, but Kimball, who did not identify himself, stood firm, insisting the Corcoran give the password.

When Corcoran again asked to pass, Kimball replied, “I’ll see you damned first.” Kimball reached for his sword, Corcoran said, and Corcoran shot him dead. The men of the Ninth Regiment called it an “unjustifiable and wanton killing,” but six weeks later, a military Court of Inquiry blamed Kimball, finding that he was “intoxicated and that he was not authorized in so halting (Corcoran).” No action was taken against Corcoran.

Corcoran’s health began to fail. He suffered fainting spells, which his doctors attributed to the lingering effects of imprisonment. Toward the end of 1863, his old friend Thomas Francis Meagher visited him at his camp near Fairfax Courthouse, Va. When Meagher left on December 22, 1863, Corcoran accompanied him on horseback to the Fairfax railroad station.

On the way back to camp at about 4 p.m., Corcoran fell off his horse or was thrown from it, hitting the ground hard. His aides rushed to help him and found him unconscious and convulsing. They commandeered a wagon and rushed him to camp, but he was beyond the reach of medical science. He died at 8:30 that night from “apoplexy, superinduced by the concussion of the fall,” his doctors said. He was 36 years old.

Corcoran’s body was returned to New York City for a hero’s send-off. He lay in state in the elegant Governor’s Room at New York’s City Hall for two days. More than 10,000 people passed through to pay their respects, with many mourners turned away. Flags throughout the city flew at half-mast.

On December 27, 1863, a military procession of New York militia units, including the 69th Regiment, escorted Corcoran’s body to a crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street, where a host of priests celebrated a High Requiem Mass. It was, a reporter noted, a scene of “exceeding melancholy.” A solemn military procession accompanied the flag-draped casket to Calvary Cemetery in Woodside, N.Y. Crowds lined the procession route as “(t)he Irish as well as American element turned out in strong force to accompany him to his last home,” the New York Herald reported.

Bygones were bygones. The order for the military procession and hero’s farewell was issued by none other than Major General Charles W. Sandford, whose order to march in honor of the Prince of Wales Corcoran had defied just three years earlier.