The horrors of the Civil War led to madness and suicide among many soldiers and veterans, but comparisons to modern diagnoses of PTSD are difficult.

-

May 2023

Volume68Issue3

Editor's Note: David O. Stewart has published five books of American history, including studies of Presidents George Washington, James Madison, and Andrew Johnson, and is a frequent contributor to American Heritage. His fifth historical novel, The Burning Land, is due this spring and follows the Civil War and postwar experience of a soldier in the 20th Maine Infantry regiment. While we do not typically publish footnotes, we have included them for this essay to help readers and future researchers.

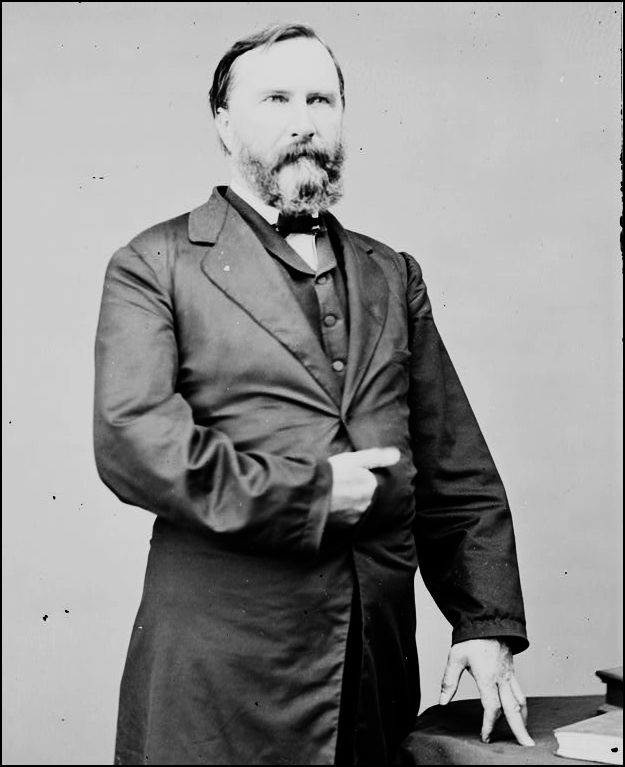

At the fiery battle of The Wilderness in early May 1864, a minié ball slammed into the shoulder of Gen. James Longstreet and burst out his throat. Blood gushed from the general’s neck as comrades took him from the field.

A West Point graduate, Longstreet knew combat. He had suffered a thigh wound in the United States invasion of Mexico in 1847. As a long-serving corps commander in the Army of Northern Virginia, Longstreet faced death in most of the battles in the Civil War’s eastern theater, plus two western campaigns. He saw men die by the thousands, observed gaping wounds and smashed bodies, and viewed acres of corpses.

Yet, after The Wilderness, something snapped inside Longstreet. One woman who attended him during a lengthy recuperation noted that the general “is very feeble and nervous. . . He sheds tears on the slightest provocation and apologizes for it. He says he does not see why a bullet going through a man’s shoulder should make a baby of him.”

After five months, Longstreet’s emotions settled enough for him to return to active duty, though his right arm would always remain paralyzed and he never would again raise his voice above a hoarse whisper.

Two years before, a corporal from Michigan, John Hildt, lost his right arm in the Seven Days Battle in Virginia, then was confined to the Government Hospital for the Insane, suffering from “acute mania.” He remained there until his death forty-nine years later.

Civil War soldiers on both sides endured horrors. Their chances of dying in uniform have been estimated at one in four; that risk for U.S. soldiers in the Korean War was 1 in 126. The psychic strains were many and recurring: fear of rampant disease and determined enemies; grisly scenes of violent killings, dismemberments, even decapitations; handling dead bodies or killing another human, which many found odious. Those pressures led to madness and suicide among soldiers like Georgia infantryman John Williams, General Philip St. George Cocke of Virginia, and Captain Thomas Pickens Butler of Kershaw’s Brigade of South Carolina.

Future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., a Union officer who fought in several Virginia battles, observed to his mother in the summer of 1864 that “many a man has gone crazy since this campaign began from the terrible pressure on mind and body.” Captain Holmes soon resigned his commission, explaining that fear “demoralizes me as it does any nervous man.”

Private Louis Beckhardt of Connecticut lost his wits after an artillery shell exploded a comrade’s head while the man drank from Beckhardt’s canteen. The stunned Beckhardt, who was covered with gore, landed in the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C. (later renamed St. Elizabeth’s). The institution offered little treatment beyond rest: patients were kept quiet, sometimes given opiates or whiskey, and might engage in light labor like gardening.

One unlucky regiment, the 16th Connecticut, landed in the thick of the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, only three weeks after being mustered. Unready for war, most of them ran. Eighteen months later, they were trapped in a siege in Portsmouth, North Carolina, captured en masse, and sent to the dismal Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. A recent study tracked more than a dozen survivors to the Connecticut Insane Asylum in Middletown, the Hartford Retreat for the Insane, the Illinois state asylum, and several committed suicide.

A single conflict might be enough to unnerve a soldier. After the Battle of Belmont in 1861, William T. Shepherd of an Illinois regiment wrote of nights tormented by dreams of “a visionary battle – sometimes victorious and, at others, utterly defeated.” Equally, extended combat exposure eroded an entire regiment’s fitness for service.

These soldiers, and many others, displayed symptoms that, since 1980, have been called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which guides psychiatric treatment, says that PTSD is present if a person experiences some combination of (i) having been exposed to a traumatic event, (ii) reliving that event, (iii) being estranged from others or fearing the future, (iv) experiencing poor sleep, poor concentration, and/or exaggerated startle responses, (v) having impaired social skills.

Clinicians and therapists tend to view PTSD as a condition that has been part of the world as long as people have endured ghastly events. Indeed, the symptoms of PTSD were recorded well before 1980. PTSD antecedents include the widespread diagnosis of “shell shock” in World War I soldiers who endured prolonged bombardments during trench warfare. During World War II, “battle fatigue” and “combat fatigue” became popular terms for similar reactions. Indeed, psychic damage from combat has been described for millennia, beginning with the ancient Mesopotamian myth of Gilgamesh, through the Greeks (as in Herodotus and Achilles sulking in his tent in Homer’s Iliad), the Romans (Lucretius), the Icelandic sagas, and in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Henry IV, Part 1.

Some historians and anthropologists cast a skeptical eye on retrospective PTSD diagnoses. Catastrophic events, one has written, have always brought “unhappiness, despair, and disturbing recollections, but no traumatic memory.” Only modern culture and psychiatrists, he contends, invented the idea of PTSD.

Physicians in the 1860s had neither the DSM nor the concept of PTSD. Many doctors viewed soldiers with such symptoms as “malingerers,” cowards, or men of low character. In truth, disturbed soldiers tended to straggle toward the army’s rear as battle approached, much like the protagonist in Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage.

The Victorian culture that demanded manliness and strength could not readily acknowledge mere mental injuries. Soldiers, however, could be charitable about comrades who showed mental derangement, calling them “played out” or “broke down,” the latter term anticipating the nervous breakdown of the twentieth century.

Civil War historian Peter Cozzens notes that there was a great deal of malingering during battle, especially toward the war’s conclusion. “Entire units,” he said, “at Petersburg and during the Overland Campaign (in 1864), refused to go forward.” Those refusals might have reflected PTSD-like symptoms, he added, or may have been rational decisions not to risk death in a war that had to end soon.

Cozzens discourages comparing the postwar treatment for mental damage suffered by Civil War soldiers with the therapeutic tools available to veterans today. He adds that Confederate and Union soldiers had the advantage of returning family and friends, while many northern regiments organized regular reunions. Those factors offered support generally less widely available to today’s veterans.

The few nineteenth-century physicians who tried to understand the mental damage inflicted on soldiers tended to focus on physical symptoms. A common term for symptoms of depression among soldiers was “nostalgia” or “nostalgic melancholia.” A Philadelphia doctor, Jacob Da Costa, reported after the war on a soldiers’ condition he called “irritable heart” – an elevated pulse rate triggered by the agitation of reliving a trauma, and then experiencing its terrors anew. Those symptoms today might be diagnosed as a panic attack. Da Costa’s concern, however, was with the patient’s heart, not with emotional strain that disrupted cardiac functions.

A British physician in the same era reported on a related phenomenon he called “railway spine.” John Eric Erichsen addressed the experience of survivors of horrific railroad accidents who – without apparent physical injury – experienced fatigue, loss of balance, headaches, fear, and spinal-column pain. Erichsen theorized that the symptoms derived from compression or inflammation of the spinal column due to a train’s routine jolts and jerks.

Twenty years later, a German physician, Hermann Oppenheim, renamed Erichsen’s railway spine as “traumatic neurosis.” Oppenheim traced the condition to brain dysfunctions, or perhaps shock and agitation, which is closer to current thinking. To thwart the nineteenth-century plaintiffs’ lawyers, railroad and insurance companies embraced Oppenheim’s theory; if the mental symptoms reflected an individual’s hysterical personality rather than a physical injury, then “much less money – if any – need be paid.”

For the last quarter of a century, beginning with Eric Dean’s book Shook Over Hell, American scholars have excavated Civil War medical records and soldiers’ writings to correlate the mental injuries during that conflict with our current understanding of PTSD. The challenge is considerable. Fully reliable diagnoses are impossible so long after the fact.

Yet those who cared for those wounded soldiers recorded the mental imbalance and anguish they experienced. One nurse in Union Army hospitals, future novelist Louisa May Alcott, described her sleeping charges growing “stern and grim, . . . evidently dreaming of war, as they gave orders, groaned over their wounds, or damned the rebels vigorously.”

The Confederate Army kept few medical records that facilitate this research, while Union Army records were created by physicians who had no vocabulary to describe psychological damage from combat. The official tally for Union soldiers was 301 suicides during the war (no postwar suicide statistics are available), 908 soldiers discharged for insanity, and 2,603 held at the Government Hospital for the Insane. Those numbers very likely understate those who suffered mental injuries among the more than 2.6 million men under arms on the Union side.

When soldiers returned home, family members struggled to understand how the soldier had developed paralyzing fears, physical symptoms like trembling, withdrawal, or periodic incoherence. Employers feared hiring veterans with odd behaviors, while a shrinking postwar economy made it more difficult for ex-soldiers to reestablish financial solvency.

Consequently, some mentally injured veterans slid into poverty, or turned to crime, or entered public homes for ex-soldiers established by state governments. Some disturbed veterans went “on the tramp,” using the nation’s expanding railroad system to satisfy their restlessness. Congress approved pensions for wounded and disabled veterans, but that largesse did not extend to those with mental and emotional scars.

While I was writing The Burning Land, a fictionalized treatment of the Civil War experience of an ancestor, I could hardly omit the horrors faced by the protagonist in a dozen battles during twenty-six months of service. Even the most stable individuals suffer from such stress, while the more fragile face breakdown or worse. No personality could be the same after that experience, so the war had to change my protagonist, as well.

Despite the incomplete data, the complexity of human behavior, and the perils of applying twenty-first century ideas to nineteenth-century lives, the study of mental injuries during the Civil War underscores the grueling sacrifices made by soldiers in that war and for years after.

Such studies also inform the costs we assume whenever we send soldiers onto modern, industrialized battlefields with calls for honor and promises of glory. Those costs – often called the butcher’s bill – is incomplete without considering the psychic injuries suffered even by those without visible scars. The principal goal of the the federal government in the Civil War, ending human slavery, was as noble a purpose as any American war has claimed, but the butcher’s bill is incomplete without reckoning the invisible scars inflicted on so many.