In a momentous couple of years, the young United States added more than a million square miles of territory, including Texas and California.

-

Summer 2024

Volume69Issue3

Editor’s Note: One of the leading historians of the West, Elliott West has recently published Continental Reckoning: The American West in the Age of Expansion, from which he adapted this essay.

Between February 19, 1846 and July 4, 1848, the United States acquired more than 1.2 million square miles of land. It was, far and away, the greatest expansion in the nation’s history, more than half of what had been added in the Louisiana Purchase more than four decades earlier. If the nation were to add that much today, expanding not to the west but to the south, our borders would embrace all of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama, and more than half of Colombia.

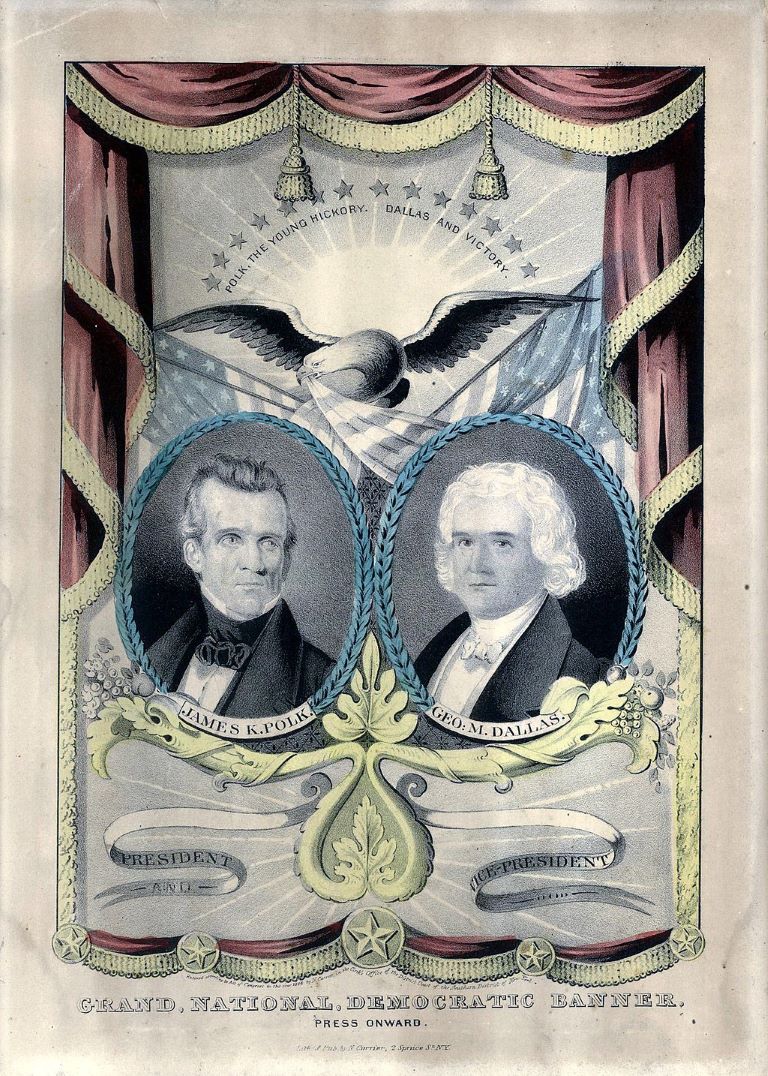

The expansion between 1845 and 1848 came in three interrelated episodes. The first was the annexation of Texas. In 1836, it had won its independence from Mexico, though Mexico continued formally to consider it a state in rebellion. Although opinion in Texas strongly favored joining the United States, a growing sentiment in the Northeast against expansion of African American slavery scuttled the possibility. For ten years, Texas would remain its own nation. By then, factions in the Democratic party strongly favored inviting the Lone Star Republic, and when the favorite candidate for the 1844 nomination, Martin Van Buren of New York, opposed it, the party turned instead to James Knox Polk of Tennessee, who campaigned for annexing both Texas and the Oregon Country of the Pacific Northwest—territory strongly desired by voters in the anti-Texas Northeast. Polk’s strategy, that is, was to offset opposition to some expansion, not by hedging his support for it, but by promising to expand still more. When he narrowly defeated the Whig stalwart Henry Clay of Kentucky, his victory was widely assumed to be a popular approval of a vigorous and general expansion.

See also "Polk's Peace" by Robert Merry

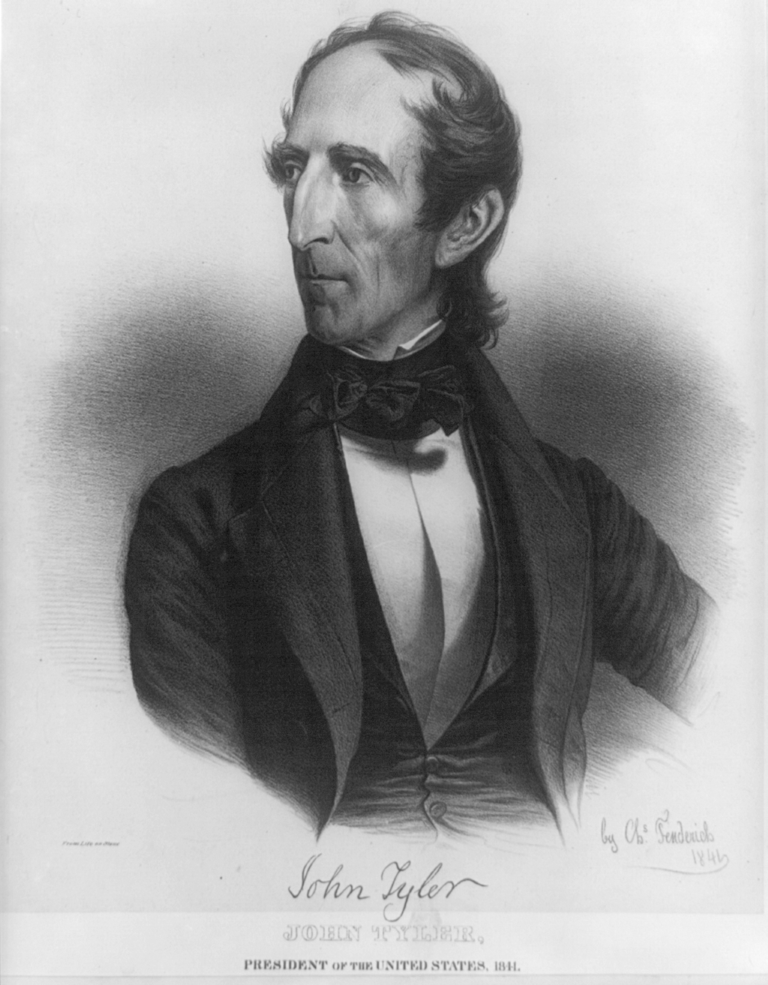

Polk’s predecessor, John Tyler, an expansionist who had been read out of the Whig party for his views, had negotiated a treaty of annexation, but the Senate rejected it after the new secretary of state, John Calhoun, publicly linked it to the preservation of Black slavery. Tyler, arguing that voters had made their wishes clear, called for inviting the republic through a constitutionally dubious joint congressional resolution that needed only simple majorities in both houses. That passed by a whisker. On the eve of his departure from the Oval Office, Tyler extended the offer to Texas, which approved annexation in a summer convention and by popular vote in the fall. Polk signed legislation admitting Texas two days before the end of 1845, and on February 19, 1846, Texas formally relinquished its sovereignty to the United States. The first gulp of new land was done.

The second was entwined with it. James Polk had courted Northeastern support by calling for acquiring the “Oregon Country,” territory from the northern boundary of present-day California to the 54th parallel, 40 minutes, which is now the southern boundary of Alaska. East to west, it went from the continental divide to the Pacific Ocean. Spain and Russia had abandoned claims to the area, and the United States and England had agreed to allow each other’s citizens to work and settle there and to forswear any military presence. The only land that was truly disputed was south of the 49th parallel (our current boundary with Canada) and enclosed within the long curve of the Columbia River. England’s Hudson’s Bay had profited hugely from this beaver-rich country, and fur-trade hopefuls in the United States looked on it covetously. Meanwhile, Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries were boosting the country below the Columbia River as an agrarian wonderland, and by 1844, hopeful farm families were settling the fertile Willamette River valley.

It was to such interests that Polk appealed in 1844, and, once in office, he secretly proposed a division of the Oregon Country along the 49th parallel. Through a slightly comic series of miscommunications, England seemed to refuse. Polk’s response was to break off negotiations, demand everything up to Russian America, and ask Congress to serve notice of ending the joint occupation. The implication was that he was ready to fight. The English government had in fact been amenable to Polk’s initial offer, the Hudson’s Bay Company having moved its main post to the southern tip of Vancouver Island. A new government under Prime Minister Robert Peel and his secretary for foreign affairs, Lord Aberdeen, proposed dividing along the line long considered, the 49th parallel, but bending around Vancouver Island to keep it in English hands. Polk accepted this border. For all the bluster, the confrontation was, writes historian Frederick Merk, one of a “kernel of reality and an enormous husk,” with both sides agreeing to what was likely the outcome from the start. The signing of the Oregon Treaty on June 15, 1846 gave the United States the present states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and a bit of Montana. The second gulp was accomplished.

The third, both bloodier and more complicated, brought the acquisition of California and the Southwest. Polk was committed to Texas’s claim, based on virtually nothing, that its western boundary extended to the Rio Grande in its entirety, which would include Santa Fe, the mercantile and political center increasingly bound by trade to the Missouri Valley. Like the three presidents before him, he had further ambitions beyond Texas. California’s Central Valley had a ripening reputation of an agrarian paradise and had already drawn small but growing numbers of farmers. There were, besides, California’s ports, above all the bay at San Francisco, increasingly regarded as one of the world’s finest, and which was nicely situated as a base for trade of whatever sort around the Pacific.

This left President Polk playing a double, and contradictory, diplomatic game. He would press Mexico to recognize Texas annexation—to accept, that is, what Mexico considered an invasion—while also trying to persuade it to sell California and the Southwest, which was central to his own political goals. It did not go well. In December of 1845, he sent John Slidell of Louisiana to offer up to $25 million to settle disputes and acquire New Mexico and California, but Polk sent him as minister plenipotentiary, which, in diplomatic language, meant that meeting with him would imply that relations were reestablished, which, in turn, would imply that Mexico had accepted of the loss of Texas. A rebuffed Slidell wrote home that “a war would probably be the best mode” of getting what was desired.

General Zachary Taylor and 4,000 troops were already on the Nueces River, the actual extent of the Texans’ occupation, and Polk now sent them down to the Rio Grande, as he clearly looking for a confrontation. None came. Polk was about to ask for a declaration of war based on Mexico’s delinquency in paying a $2 million debt when word arrived that a Mexican cavalry command had engaged American dragoons north of the Rio Grande and killed 11 soldiers. Polk hastily rewrote his address to allege that Mexico had invaded the United States and that “American blood had been shed upon the American soil.” With some Whig opposition, Congress assented.

Many in Washington predicted a short and successful war. They were disappointed. Mexico put up far greater resistance than expected, and once its defeat was obvious, it was reluctant to concede. Taylor took Matamoros and Monterrey, and in February 1847, his outnumbered men defeated an untrained and exhausted command under Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna at the village of Buena Vista, near Saltillo.

Texas was secure. New Mexico had been taken six months earlier. As Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny led the newly created Army of the West from Fort Leavenworth in Kansas toward Santa Fe, a group of influential Anglos argued persuasively to Governor Manuel Armijo that his position was untenable. Armijo negotiated a bloodless surrender and took off for Chihuahua. Local resentment, especially among the clergy and Pueblo Indians, erupted in a rebellion in Taos, north of Santa Fe, that killed the new governor, Charles Bent, and a few other officials, but troops from Santa Fe commanded by Colonel Sterling Price suppressed the revolt after just over two weeks.

Six days before the rebellion, a treaty had secured California, at least on paper. In the summer of 1845, Colonel John C. Fremont had led a well-armed expedition there, supposedly to explore, but clearly meant to support, if not incite, a Texas-style rebellion. In mid-June of 1846, a gaggle of Americans took the town of Sonoma in northern California, tapped Fremont to lead them, and declared their independence, two days before Commander John Sloat arrived from Hawaii—he had been told a year earlier to take San Francisco if war began—and announced (without authority) California’s annexation.

The conquest appeared complete, but in September, Californios (Hispanic locals) struck back and took full control of much of Southern California. Even after Stephen Kearny arrived from New Mexico with a few hundred dragoons, he and Commander Robert Stockton, who had replaced Sloat, had their hands full until Fremont joined them from up north. On January 13, 1847, a treaty with the Californios ended the resistance.

By late February 1847, American forces had taken control of all the territory that Polk had wanted, but, with Mexican popular opinion virulently against the gringos, Santa Anna’s government showed no sign of capitulating.

The decision was made to force the point by moving on Mexico City. After directing the first large-scale amphibious landing in his nation’s history, Major General Winfield Scott took the seemingly impregnable port city of Veracruz, bested Santa Anna’s numerically superior force at the Battle of Cerro Gordo, and took the extraordinary risk of cutting loose from his support on the coast to lead more than 8,000 troops overland to Mexico City. He moved in stages over four months, allowing chances for his opponents to discuss terms, and arrived at the capital in August. Advancing unexpectedly from the south, Scott’s force took the protective height of Chapultepec on September 13. The next day, Santa Anna withdrew his troops, and the city surrendered. Except for some guerilla assaults, the war was over.

The peace, however, was more than four months away. The path to it was made difficult by the popular loathing of the norteamericanos in Mexico, by its roulette of political affairs, and by the shifting of positions and opinions in Washington. Polk’s negotiator, Nicholas Trist, first offered to pay almost what had been offered for the areas originally sought, plus Baja California and the rights to a canal across Mexican lands. Santa Anna (once again president) declined. Polk, reminiscent of when he extended his demands on the Oregon Country, insisted that Mexico hand over a sizable part of its northern territory, and ordered Trist to come home.

Then, Santa Anna was ousted again. When his replacement seemed more amenable, Trist, fearing with good reason that the situation might dissolve into chaos, chose to buck the president’s order and press for a resolution. After protracted discussions and some amendments, an agreement was struck. An enraged Polk had Trist brought home in custody, but, facing growing political turmoil, he followed Trist’s reasoning and submitted the treaty. The Senate approved it on March 10, 1848, as did the Mexican legislature on May 19.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, acknowledged Texas’s annexation and passed over to the United States all of today’s California, Nevada, and Utah, as well as most of Arizona, western portions of Colorado and New Mexico, and a tad of Wyoming. In return, the United States paid Mexico $15 million and assumed its debt to American citizens, now grown to a bit more than $3 million. Full citizenship was promised to all Mexican citizens who chose to relinquish their former allegiance. Washington agreed to control the Indian peoples on its side of the new border and to pay for damages resulting from its raids to the south—a commitment that proved full of problems and exceptionally expensive. The costs of any war, in human and financial terms, are ultimately incalculable, but the official tally for the United States was more than 13,000 dead, most from disease, and close to $150 million in expenses incurred in the field, in payments from the treaty, and in veterans’ benefits over the years.

When the land-gorging of 1845 to 1848 was complete, and with the after-dinner mint of the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the boundaries of the contiguous United States were set. It was quite a growth spurt. In only a little more time than that between a child’s birth and its speaking its first simple sentences, the United States expanded by 773,510,680 acres, more or less.

Looking back on these events, it is easy enough for Americans to see them as serendipity (and, for Mexicans, its opposite). There were so many turns of chance. So striking were these that it is easy to miss a critical underlying point. While each moment was a proximate step in expansion, all were responses to pressures and interests that had been building for the previous few decades. Four in particular go a long way toward explaining not only this massive expansion of U.S. territory, but also the events that followed it.

Begin with population. The number of Americans more than tripled between 1800 and 1840, from 5.3 million to 17 million, and, even with the size of the nation doubling with the Louisiana Purchase, the density of population per square mile grew by 60 percent. While the economy was shifting toward early industrialization, most families were engaged in agriculture or closely related enterprises, and, with a high birth rate, each generation multiplied considerably the number of families hoping to start a farm. On the eve of expansion, the nation was increasingly crowded, at least by standards of the time, and basic math pushed the demand for land inexorably upward.

Southern states could look beyond Louisiana and Arkansas to Texas, which, by 1845, had a white population edging toward 100,000, plus about 30,000 black slaves. Families in the Ohio Valley and around the Great Lakes could look to Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa, but the considerable land west of there was effectively off the agrarian table. This was “Indian Country.” It had no political organization, had no effective connections to the East, and, it was thought, received too little rain for families to farm in accustomed ways. Plenty of land was still available in the Ohio Valley, but the rapid population growth led many Americans to conclude that agricultural expansion might stall, which encouraged a search for places that were friendly to farmers and their futures.

Thus, Polk’s twin appeal in 1844 in pledging to annex Texas and acquire Oregon. Reports from Oregon gushed about its agricultural potential, especially in the valley of the Willamette River, where the early booster Thomas Farnham described as an arable corridor, 150 miles long by 60 miles wide, of rich vegetable mold three feet deep. In 1838, the era’s great storyteller, Washington Irving, published a popular account of the party sent by John Jacob Astor to establish a post on the Northwest shore in 1811-12. Astor reported a “serene and delightful” climate in coastal Oregon. One could “sleep in the open air with perfect impunity” and stand in the shade in high summer without breaking a sweat. As farmland in the East filled, Oregon beckoned, and by 1844, a couple of thousand Americans had settled there, with more on the way. They were drawn by the prospect, in the phrase of the day, that, if you planted a nail, it would come up a spike.

A second demand was for commercial access to the Pacific world. Once Oregon became part of the United States, John Fremont predicted in 1844, it would become “a thoroughfare for the East India and China trade” that Senator John Calhoun was sure would funnel goods and wealth from half the people on the planet straight to the Mississippi Valley and beyond. That vision included California. Twenty-five years before the United States acquired Oregon and California, a New England congressman assured his colleagues that, once the “swelling tide” of Americans had reached the Pacific, “the commercial wealth of the world is ours, and imagination can hardly conceive the greatness, the grandeur, and the power that awaits us.” In the years ahead, a trade in sea otter furs and California cattle hides, plus a vigorous increase in whaling turned the interests of New Englanders increasingly to the Pacific coast and the prospect of trade beyond it. Geography, however, posed a problem. Much of the Pacific coast consists of cliffs and heights, so interest came to focus on a handful of usable ports. In Oregon, the Fuca Strait and Puget Sound had several good harbors, but to the south were only San Francisco, Monterey, and San Diego. “The glory of the western world,” is how the explorer Thomas Farnham described San Francisco’s long, deep, wide, and placid bay. Even its bordering capes were “verdant and refreshing to the eye.”

A third force was a quarter century of exploration of land to the west, the tracing of routes of transit, and the development of new means of moving across and around the vast territory. The first overland emigrants in 1841 took paths used over the previous 20 years by fur trappers. Over the following five years, Lt. John Charles Fremont of the Corps of Topographical Engineers led a series of ambitious expeditions that clarified the road to Oregon, established a route across the Sierra Nevada, described parts of the Great Basin and central California, and reported on a trading route across the Southwest. His hugely popular official reports, written by his brilliant wife, Jessie, were essentially enticements that left readers feeling, as the historian William Goetzmann suggests, that James Polk’s push westward was not just acceptable but, to many, inevitable.

The marking of ways into the West occurred at a time when the nation and the world were, in practical terms, shrinking. New Englanders were especially interested in Pacific ports, in part because new ship designs had shortened the effective distance between Boston and San Francisco and between San Francisco and Hawaii and Hong Kong. By the 1840s, the canals that had directed movement in the East were showing up in westering dreams. President Polk sought the rights to build a great canal across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; Texas expansionists proposed one to link Galveston and the Gulf of California.

Two new technologies accelerated this revolution in transcontinental movement. In May 1844, as Fremont was on his second expedition, Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail officially tested the telegraph system that would soon span the globe. A month earlier, the New York merchant Asa Whitney had arrived in San Francisco after more than a year in China. He was soon America’s most impassioned advocate of the second technology, the railroad, as a link between the East, Pacific ports, and Asian trade. Seven months after the Senate approved the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Fremont set out with 35 men to find a usable Pacific rail route across the Rocky Mountains. Washington sent Howard Stansbury to do the same up the Great Platte River Road in Nebraska and through the Wasatch Mountains to the Great Salt Lake.

By the mid-1840s, the fourth development had given the vision of moving westward, quite literally, a distinctive coloration. There was a widely held conviction that expansion was both ordained and demanded by the nation’s cultural and racial superiority. Exponents of white expansion believed that the world’s peoples were arranged in a racial order, with Caucasians at the top, and Anglo-Saxons at the top of the top. The true homes of these superior tribes were northern Europe, Germany, and especially England, and the United States — places where, unsurprisingly, these theories began and flourished the most. Descriptions of the western land’s beauty and promise were joined to accounts of peoples alleged to be stunted in development and incapable of making of the country what God intended it to be. In a small masterpiece of circular reasoning, Thomas Farnham described the elite Californios as men of “not a very seemly” bronze, naturally indolent, and of “lazy color.”

All of these racist, expansionist impulses drew on and reinforced each other. Anglo-Saxon farmers needed western land that, by happy chance, was properly theirs because retrograde Mexicans and Indians could never bring it to bloom. The railroads that promised to expand the nation’s commerce and power were proof of Anglo America’s intellectual superiority and higher civilization. That left Americans obligated to reach farther, into the Pacific. Asa Whitney promoted the idea of a rail line to the West coast that not only would benefit American farmers and merchants, but, in time, would also feed starving Chinese and bless “the heathen, the barbarian, and the savage . . . with civilization and Christianity.”

The expansion of 1845-48 was both a child of chance and the product of forces that had been building for a quarter century. By 1845, those forces had come together under a gloss of confidence, summed up in the term “manifest destiny,” that the United States was bound to dominate the lands between its current border and the Pacific. When the nation did in fact expand with such stunning speed, it was natural to assume that what had brought the expansion would just as surely confirm America’s command of the new country and its promised rise to new greatness.

Every force behind expansion was unloosed into the new America. In time, expansion would indeed play vitally in the nation’s steep rise in affluence and power. At the outset, however, that was anything but obvious. The events of 1845 to 1848 came close to destroying the republic. The first fruits of this expansion were turbulence, uncertainty, and the most contentious and violent time in American history.