A story that the Confederate president donned a petticoat to evade capture emerged right after Union cavalrymen apprehended him in Georgia at war’s end. Is it true?

-

Fall 2010

Volume60Issue3

On Sunday, May 14, 1865, Benjamin Brown French, commissioner of public buildings for the District of Columbia, left his home on Capitol Hill to buy a copy of the Daily Morning Chronicle. “When I came up from breakfast I went out and got the Chronicle,” he wrote in his journal, “and the first thing that met my eyes was ‘Capture of Jeff Davis’ in letters two inches long. Thank God we have got the arch traitor at last.”

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles also noted the Confederate president’s capture in his diary: “Intelligence was received this morning of the capture of Jefferson Davis in southern Georgia. I met Secretary of War Edwin Stanton this Sunday p.m. at Seward’s, who says Davis was taken disguised in women’s clothes. A tame and ignoble letting-down of the traitor.”

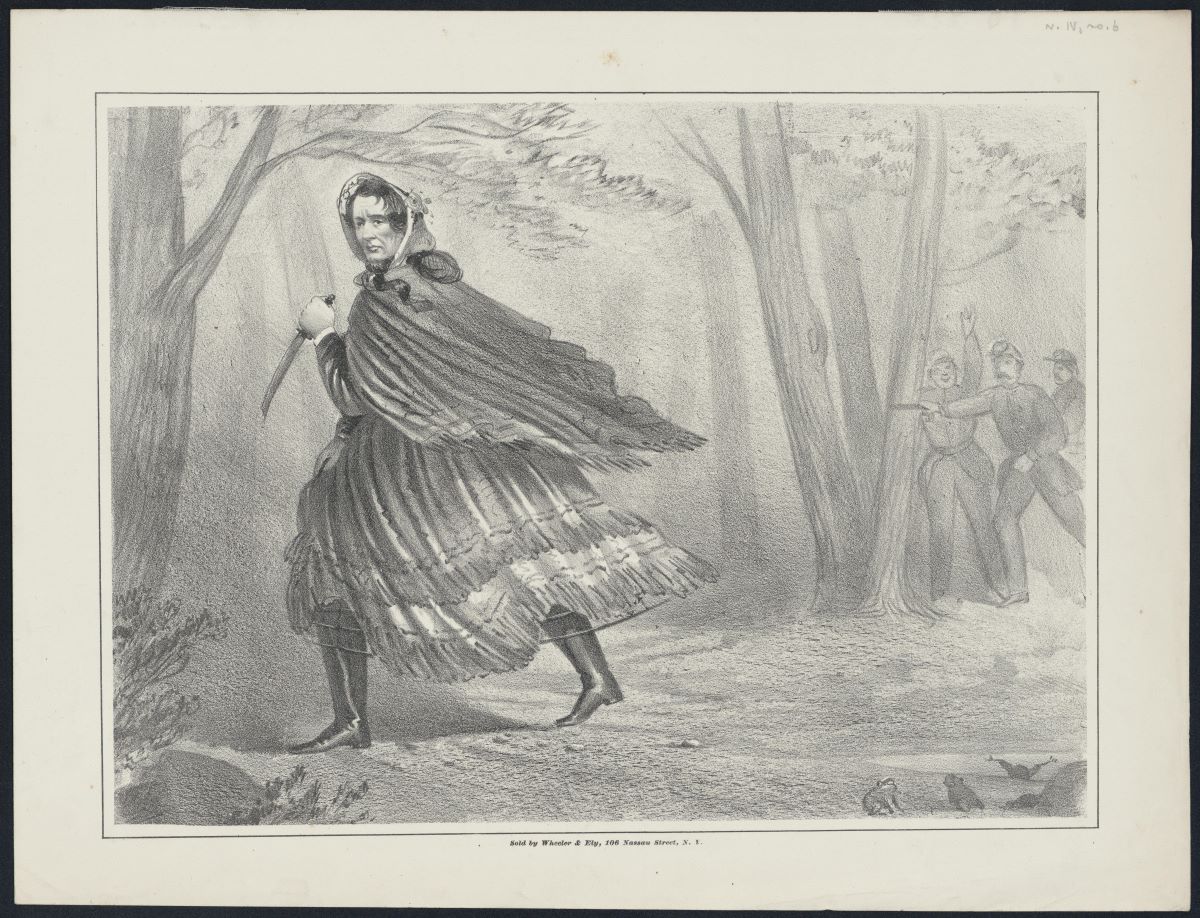

The story of Jefferson Davis’ capture in a dress took on a life of its own, as one Northern cartoonist after another used his imagination to depict the event. Printmakers published more than 20 different lithographs of merciless caricatures depicting Davis in a frilly bonnet and voluminous skirt, clutching a knife and bags of gold as he fled Union troopers. These cartoons were accompanied with mocking captions, many of them delighting in sexual puns and innuendoes, and many putting shameful words in Davis’s mouth. Over the generations, fact and myth have comingled concerning the details of Davis’s final capture. Had he borrowed his wife’s dress to evade the Union cavalry? How much of the unflattering post capture cartoons, news reports, and song lyrics sprang from the deep bitterness Northerners held for the man who symbolized the Confederacy?

A little more than a month earlier, on April 10, President Abraham Lincoln and the inhabitants of the nation’s capital woke to the sound of an artillery barrage at dawn. Journalist Noah Brooks ate breakfast with the president that morning and later recalled that “A great boom startled the misty air of Washington, shaking the very earth, and breaking windows of houses about Lafayette Square. . . . Boom! Boom! Went the guns, until five hundred were fired.”

Lincoln had received the word the night before that Lee and his army had surrendered to Grant. The early morning salute “was Secretary of War Stanton’s way of telling the people that the Army of North Virginia had at last laid down its arms, and that peace had come again,” Brooks wrote. “Guns are firing, bells ringing, flags flying, men laughing, children cheering; all, all are jubilant.”

The whereabouts of the Confederate president, who had fled the capital of Richmond eight days earlier, was unknown. “It is doubtful whether Jeff Davis will ever be captured,” noted the New York Times. “He is, probably, already in direct flight for Mexico.”

That day found Davis preparing to leave Danville, Virginia, which had served as the final capital of the Confederacy during the previous week. He would be on the run for six weeks, an epic journey through four states by railroad, ferry boat, horse, cart, and wagon. By May 10 he would be a prisoner. Others, including his aides, would wonder for years why Davis hadn’t placed his own welfare first and escaped to Texas, Mexico, Cuba, or Europe. The Confederate Secretary of State Judah Benjamin and Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge did so and had escaped abroad.

Davis’s private secretary, Burton Harrison, who was with him when captured, pointed to “the apprehension he felt for the safety of his wife and children which brought about his capture.” Perhaps Davis was tired of life on the run, or maybe

his chronic illnesses had weakened him. Maybe he thought a few more hours of stolen rest would not matter. Perhaps he thought it was too late to escape to Texas and resuscitate a western Confederacy there. Perhaps he did not want to flee, run away to a foreign land, and vanish from history.

On May 5, after more than a month on the run and three weeks after Lincoln’s assassination, Davis and the men still traveling with him reunited with his wife, Varina, and her party in east central Georgia. Davis had not seen Varina and their four children since they had parted in Richmond. The president took his eight-year-old son Jefferson Davis Jr. shooting. Colonel William Preston Johnston observed the target practice. The president “let little Jeff. shoot his Deringers at a mark, and then handed me one of the unloaded pistols, which he asked me to carry.” When Davis and Johnston turned their discussion to their escape route, the colonel “distinctly understood that we were going to Texas.”

On May 9, Davis decided to make camp for the night with Varina’s wagon train near Irwinville. They pulled off the road, and the pine trees helped conceal their position. President Davis’s escort did not circle their wagons. If the Federals were able to surround a small camp drawn up in a tight circle, it would be difficult for Davis to take advantage of the confusion of battle and escape. Instead, Davis’ party pitched camp with an open plan, scattering the tents and wagons over an area of about 100 yards.

For reasons unknown, the camp posted no guards that night, even though they faced a genuine threat of attack from either ex-Confederate soldiers—ruthless, war-weary bandits bent on plunder—or Union cavalry on the hunt for Davis. It was no secret that bandits had been shadowing Varina Davis’ wagon train for several days, and they could strike anytime without warning. That was the reason Davis had reunited with Varina, instead of pushing on alone.

Davis had not planned on spending the night of May 9 camped with his wife and children near Irwinville. Unless he abandoned the wagon train and moved fast on horseback, accompanied by no more than three or four men, he had little chance of escape. By this time, the Union was flooding Georgia with soldiers and canvassing every crossroads, guarding every river crossing, and searching every town. Also, the Federals had recruited local blacks, with their expert knowledge of back roads and hiding places, to help in the manhunt for the fugitive president.

Davis told his aides that he would leave the camp sometime during the night. He was dressed for the road: a dark, wide-brimmed felt hat; a signature wool frock coat of Confederate gray; gray trousers; high black leather riding boots, and spurs. His horse, tied near Varina’s tent, was already saddled and ready to ride, its saddle holsters loaded with Davis’s pistols.

Several of the men stayed up late talking, waiting for the order to depart. It never came. Unbeknownst to the inhabitants of Davis’s camp, a mounted Union patrol of 128 men and seven officers—a detachment from the 4th Michigan Cavalry regiment—led by regimental commander Lieutenant Colonel B. D. Pritchard, was closing in on Irwinville.

When they got close, Pritchard and a few of his men rode into town, posed as Confederate cavalrymen, and questioned some villagers. “I learned from the inhabitants,” Pritchard later recounted, “that a train and party meeting the description of the one reported to me at Abbeville had encamped at dark the night previous one mile and a half out on the Abbeville road.”

Pritchard left Abbeville and positioned his men about half a mile from the mysterious encampment. “Impressing a negro as a guide,” Pritchard recalled, “I halted the command under cover of a small eminence and dismounted twenty-five men and sent them under command of Lieutenant Purington to make a circuit of the camp and gain a position in the rear for the purpose of cutting off all possibility of escape in that direction.”

Pritchard told Purington to keep his men “perfectly quiet” until the main body attacked the camp from the front. Although, tempted to charge the camp at once, Pritchard decided to wait until daylight: “The moon was getting low, and the deep shadows of the forest were falling heavily, rendering it easy for persons to escape undiscovered to the woods and swamps in the darkness.”

At 3:30 a.m., Pritchard ordered his men to ride forward: “Just as the earliest dawn appeared, I put the column in motion, and we were enabled to approach within four or five rods of the camp undiscovered, when a dash was ordered, and in an instant the whole camp, with its inmates, was ours.”

Still inside Varina’s tent, Davis heard the gunfire and the horses in the camp and assumed these were the same Confederate stragglers or deserters who had been planning to rob Mrs. Davis’s wagon train for several days. “Those men have attacked us at last,” he warned his wife. “I will go out and see if I cannot stop the firing; surely I still have some authority with the Confederates.” He opened the tent flap, saw the bluecoats, and turned to Varina: “The Federal cavalry are upon us.”

Davis had not undressed this night, so he was still wearing his gray frock coat, trousers, riding boots, and spurs. He was ready to leave now, but he was unarmed. His pistols and saddled horse were within sight of the tent. He was a superb equestrian and certain that he could outrace any Yankee cavalryman half his age if he could just get to a horse. Seconds, not minutes, counted now.

Before he left, Varina asked him to wear an unadorned raglan overcoat, also known as a “waterproof.” She hoped the raglan might camouflage his fine suit of clothes, which resembled a Confederate officer’s uniform. “Knowing he would be recognized,” Varina later explained, “I pleaded with him to let me throw over him a large waterproof which had often served him in sickness during the summer as a dressing gown, and which I hoped might so cover his person that in the grey of the morning he would not be recognized. As he strode off I threw over his head a little black shawl which was round my own shoulders, seeing that he could not find his hat and after he started sent the colored woman after him with a bucket for water, hoping he would pass unobserved.”

“I had gone perhaps between 15 or 20 yards,” Davis recalled, “when a trooper galloped up and ordered me to halt and surrender, to which I gave a defiant answer, and, dropping the shawl and the raglan from my shoulders, advanced toward him; he leveled his carbine at me, but I expected, if he fired, he would miss me, and my intention was in that event to put my hand under his foot, tumble him off on the other side, spring into the saddle, and attempt to escape. My wife, who had been watching me, when she saw the soldier aim his carbine at me, ran forward and threw her arms around me. . . . I turned back, and, the morning being damp and chilly, passed on to a fire beyond the tent.”

Some of the cavalrymen started tearing apart the camp in a mad scramble. They searched the baggage, threw open Varina’s trunks, and tossed the children’s clothes into the air. “The business of plundering commenced immediately after the capture,” observed Harrison. The frenzy suggested that the search was not random. The Federals were looking for something: every Union soldier had heard the rumors that the “rebel chief’ was fleeing with millions of dollars in gold coins in his possession.

Pritchard and his officers heard firing behind the camp and soon discovered that their men were fighting other Union soldiers of the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry, and they were killing each other. Greed for gold and glory contributed to the deadly and embarrassing disaster. The firing between the two regiments created tensions on both sides. Their failure to capture the expected Confederate treasure exacerbated their anger and humiliation. They blamed each other for the fratricide, accused each other of appropriating leads about Davis’s whereabouts during the chase, and fought over the reward money.

It was only after the deadly skirmish that Pritchard realized he had captured the president of the Confederate States of America. One member of Davis’s party later described the captive’s rough treatment: “A private stepped up to him rudely and said: ‘Well, Jeffy, how do you feel now?’ I was so exasperated that I threatened to kill the fellow, and I called upon the officers to protect their prisoner from insult.”

May 10, 1865 was thus the end for Jefferson Davis’s presidency and his dream of Southern independence. But it was also the beginning of a new story, one he began to live the day he was captured.

News spread of Davis’ capture—and with it the story of his apprehension in women’s clothes. The great showman P. T. Barnum knew at once that the garment would make a sensational exhibit for his fabled American Museum of spectacular treasures and curiosities in downtown New York City. He wanted the hoop skirt Davis had supposedly worn and was prepared to pay handsomely. Barnum wrote to Secretary of War Stanton, offering to make a $500 donation to one of two worthy wartime causes, the welfare of wounded soldiers or the care of freed slaves.

It was a hefty sum—a Union army private’s pay was only $13 a month—and that $500 could have fed and clothed a lot of soldiers and slaves. Still, Stanton declined the offer. The secretary had other plans for these treasures. He earmarked the captured garments for his own collection and ordered that they be brought to his office, where he planned to keep them in his personal safe along with other historical curiosities from Lincoln’s autopsy, John Wilkes Booth’s death, and Davis’ capture.

The arrival in Washington of the so-called petticoats proved to be a big letdown. When Stanton saw the clothes, he knew instantly that Davis had not disguised himself in a woman’s hoop skirt and bonnet. The “dress” was nothing more than a loose-fitting, waterproof raglan or overcoat, a garment as suited for a man as a woman. The “bonnet” was a rectangular shawl, a type of wrap President Lincoln himself had worn on chilly evenings. Stanton dared not allow Barnum to exhibit these relics in his museum. Public viewing would expose the lie that Davis had worn one of his wife’s dresses. Instead Stanton sequestered the disappointing textiles to perpetuate the myth that the cowardly “rebel chief” had tried to run away in his wife’s clothes.

The image of the Confederate president masquerading as a woman titillated Northerners but outraged Southerners. Eliza Andrews, a young woman who had witnessed Davis pass through her town of Washington, Georgia, during his escape, condemned the pictures in her diary: “I hate the Yankees more and more, every time I look at one of their horrid newspapers . . . the pictures in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s tell more lies than Satan himself was ever the father of. I get in such a rage . . . that I sometimes take off my slipper and beat the senseless paper with it. No words can express the wrath of a Southerner on beholding pictures of President Davis in woman’s dress.”

A wave of sheet music artwork and satiric lyrics followed the caricatures in newspapers and prints. Davis would spend two years imprisoned at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, before his release on bail. The federal authorities would never prosecute him. He survived Lincoln by 24 years, wrote his memoirs, and became the South’s most beloved living symbol of the Civil War. Although he devoted the rest of his life to preserving the memory of the Confederacy, its honored dead, and the Lost Cause, Jefferson Davis could never dispel the myth of his capture dressed as a Southern belle. The legend has endured.