For nearly three decades, the author has warned that, if we ignored Putin's ambitions, he would become a global problem.

-

Spring 2022

Volume67Issue2

Editor’s Note: Garry Kasparov, considered by many to be the greatest chess player of all time, was the World Chess Champion from 1985 to 2000. Since retiring from chess in 2005, he has focused on political activism and writing, speaking forcefully against anti-democratic developments in Russia. Mr. Kasparov recently published Winter Is Coming: Why Vladimir Putin and the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped, from which this essay was adapted.

On August 19, 1991, CNN was providing nonstop live coverage of an attempted coup against Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev. Allied with the KGB, hardliners from inside the disintegrating Communist regime had sequestered Gorbachev at his dacha in Crimea and declared a state of emergency. The global press was full of experts and politicians worried that the coup would mark the sudden end of perestroika, or even the start of a civil war, as tanks rolled into the middle of Moscow.

I appeared as a guest on Larry King that evening, along with former US ambassador to the United Nations Jeane Kirkpatrick, a professor from California, and a former KGB operative. I was alone in declaring that the coup had no chance of success, and that it would be over in forty-eight hours, not the months Kirkpatrick and many others were predicting. The coup’s leaders had no popular support, I insisted, and their attempt to put a halt to reforms they feared might lead to the breakup of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was doomed.

The ruling bureaucracy was also split, with many feeling they had better opportunities for advancement after a Soviet breakup. I was vindicated with great efficiency, as Russian president Boris Yeltsin famously climbed aboard a tank, the people of Moscow rallied for freedom and democracy, and the cabal of coup leaders realized the people were against them. They surrendered two days later. The coup attempt not only failed, but it accelerated the demise of the Soviet Union by presenting the people of the USSR a clear choice. Dissolution and an independent future were a little frightening, yes, but it could not be worse than the totalitarian present.

Like dominoes, republic after Soviet republic declared independence in the following months. Back in Moscow, two days after the failure of the coup, a jubilant crowd tore down the statue of “Iron” Felix Dzerzhinsky, the fearsome founder of the Soviet secret police, in front of the KGB headquarters.

It is difficult for me now to read the comments members of that crowd made to the press without becoming emotional. “This begins our process of purification,” said a coal miners’ union leader. An Orthodox priest said, “We will destroy the enormous, dangerous, totalitarian machine of the KGB.” The crowd chanted “Down with the KGB!” and “Svo-bo-da!” the Russian word for freedom. Police took off their berets to join the march as messages like “KGB butchers must go to trial!” were scrawled on the base of the hated statue. A doctor said this protest was different from those of the previous month: “We feel as though we have been born again.”

And so it shocked the imagination that eight years later, on December 31, 1999, a former lieutenant colonel of the KGB became the president of Russia. The country’s nascent democratic reforms were halted and steadily rolled back. The government launched crackdowns on the media and across civil society. Russian foreign policy became bullying and belligerent. There had been no process of purification, no trials for the butchers, and no destruction of the KGB machine. The statue of Dzerzhinsky had been torn down, but the totalitarian repression it represented had not. It had been born again — in the person of Vladimir Putin.

Jump forward to the beginning of 2022 and Putin is still in the Kremlin. Russian forces have brutally attacked Ukraine and annexed Crimea, after invading another neighbor, the Republic of Georgia in 2008. Just days after hosting the Winter Olympics in Sochi in February 2014, Putin fomented a war in Eastern Ukraine and became the first person to annex sovereign foreign territory by force since Saddam Hussein in Kuwait.

The same world leaders who were taking smiling photos with Putin recently are now bringing sanctions against Russia and members of its ruling elite. Russia threatens to turn off the pipelines that supply Europe with a third of its oil and gas. A metaphorical mafia state with Putin as the capo di tutti capi (boss of all bosses) has moved from being an ideologically agnostic kleptocracy to using blatantly fascist propaganda and tactics while claiming to fight “neo-Nazis.” The long-banished specter of nuclear annihilation has returned.

There are two stories behind the current crisis. The first is how Russia moved so quickly from celebrating the end of Communism to electing a KGB officer and then invading its neighbors. The second is how the free world helped this to happen, through a combination of apathy, ignorance, and misplaced goodwill. It is critical to figure out what went awry, because even when Putin became a clear and present danger, Europe and America were still getting it wrong.

The democracies of the world must unite and relearn the lessons of how the Cold War was won before we slide completely into another one. Putin’s Russia is clearly the biggest and most dangerous threat facing the world today, but it is not the only one. Terrorist groups like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State are (despite the latter’s name) stateless and without the vast resources and weapons of mass destruction Putin has at his fingertips. The attacks of 9/11 and others like it, however, taught us that you don’t have to have a national flag or even an army to inflict terrible damage on the most powerful country in the world.

What’s more, state sponsors of terror are benefiting as their democratic targets fail to organize an aggressive defense. The murderous regimes of Iran, North Korea, and Syria have enjoyed considerable time at the bargaining table with the world’s great powers while making no significant concessions. It’s not new to talk about the challenges of the multipolar world that arose with the end of the Cold War. What is lacking is a coherent strategy to deal with these challenges.

When the Cold War ended, the winners were left without a sense of purpose and without a common foe to unite against. The enemies of the free world have no such doubts. They still define themselves by their opposition to the principles and policies of liberal democracy and human rights, of which they see the United States as the primary symbolic and material representative. And yet we continue to engage them, to negotiate, and even to provide these enemies with the weapons and wealth they use to attack us. To paraphrase Winston Churchill’s definition of appeasement, we are feeding the crocodiles, hoping they will eat us last.

Any political chill between Washington, DC, and Moscow or Beijing was quickly criticized by both sides as a potential “return to the Cold War.” The use of this cliché was ironic, given that the way the Cold War was fought and won has been forgotten instead of emulated. Instead of standing on principles of good and evil, of right and wrong, and on the universal values of human rights and human life, we have engagement, resets, and moral equivalence. That is, appeasement by many other names.

The world needs a new alliance based on a global Magna Carta, a declaration of fundamental rights that all members must recognize. Nations that value individual liberty now control the greater part of the world’s resources as well as its military power. If they band together and refuse to coddle the rogue regimes and sponsors of terror, their integrity and their influence will be irresistible.

The goal should not be to build new walls to isolate the millions of people living under authoritarian rule, but to provide them with hope and the prospect of a brighter future. Most of us who lived behind the Iron Curtain were very aware that there were people in the free world who cared and who were fighting for us, not against us. And knowing this mattered.

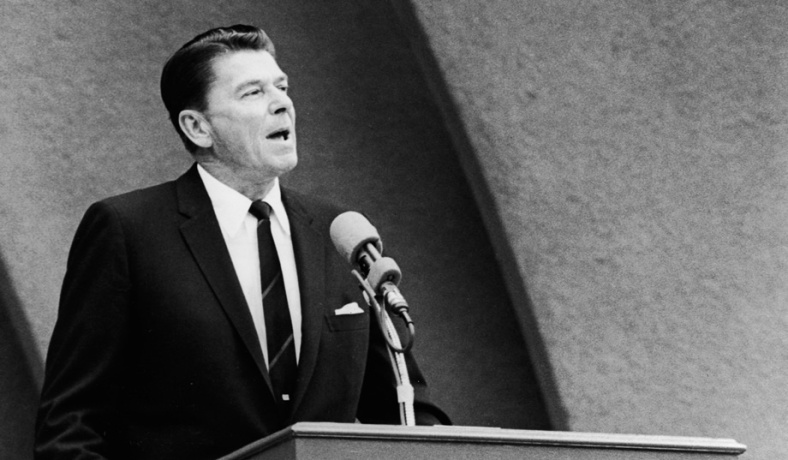

Today, the so-called leaders of the free world talk about promoting democracy while treating the leaders of the world’s most repressive regimes as equals. The policies of engagement with dictators have failed on every level, and it is past time to recognize this failure. As Ronald Reagan said in his famous 1964 speech “A Time for Choosing,” this is not a choice between peace and war, only between fight or surrender. We must choose. We must not surrender. We must fight with the vast resources of the free world, beginning with moral values and economic incentives and with military action only as a last resort. America must lead, with its vast resources and its ability to mobilize its fractious and fractured allies.

But it is obsolete today to speak of American values, or even of Western values. Japan and South Korea must act, Australia and Brazil, India and South Africa, and every country that values democracy and liberty and benefits from global stability. We know it can be done because it has been done before. We must find the courage to do it again.

Five years after Putin took office and began to rebuild the Russian police state he so admired, I experienced a rebirth of my own. In 2005, I retired from twenty years on top of the professional chess world to join the fledgling Russian pro-democracy movement. I had become world champion in 1985 at the age of twenty-two and had achieved everything I could want to achieve at the chessboard. I have always wanted to make a difference in the world and felt that my time in professional chess was over.

I wanted my children to be able to grow up in a free Russia. And I remembered the sign my mother once put up on my wall, a saying of the Soviet dissidents: “If not you, who else?” I hoped to use my energy and my fame to push back against the rising tide of repression coming from the Kremlin.

Like many Russians, I was troubled by the KGB background of the little-known Putin and his sudden rise to power by overseeing the brutal 1999 war to pacify the Russian region of Chechnya. But along with my countrymen, at the start I was grudgingly willing to give Putin a chance. Yeltsin had badly tarnished his democratic credentials during his 1996 reelection by using the powers of the presidency to influence the outcome, and I confess that I was one of those who thought at the time that sacrificing some of the integrity of the democratic process was the lesser evil if it was required to keep the hated Communists from regaining power. Such trade-offs are nearly always a mistake, and it was in this case, as it paved the way for a more ruthless individual to exploit the weakened system.

The 1998 default had left the Russian economy in a very shaky state, although it is worth pointing out in hindsight that gross domestic product (GDP) growth had already rebounded well by 2000. But at the time, crime, inflation, and a general sense of national weakness and uncertainty made the technocratic and plainspoken Putin an appealingly safe option.

There was a feeling the country could slip into chaos without a stronger hand on the helm. Physical and social insecurity have always been easy targets in fragile democracies, and most dictators rise to power with initial public support. Throughout history, endless cycles of autocrats and military juntas have been empowered by the people’s call for order and “la mano dura” (hard hand) to rein in the excesses of a wobbly civilian regime. Somehow people always forget that it’s much easier to install a dictator than to remove one.

Of course, I did not expect my new career in what can only generously be called Russian “politics” to be an easy one. The opposition was not trying to win elections; we were fighting just to have them. That’s why I always said I was an activist, not a politician, even when I won an opposition primary for the 2008 presidential election. Everyone knew I would never be allowed to appear on an official ballot; the point was to expose that fact and to try to strengthen the atrophied muscles of the Russian democratic process.

My initial goal was to unite all of the anti-Putin forces in the country, especially those that ordinarily would never imagine even being seen together. The liberal reformer camp I belonged to had nothing in common with the National Bolsheviks, for example, except for being marginalized, persecuted, and betrayed by Putin’s plan to hold on to power for life. And yet our fragile coalition marched in the streets of Moscow and St. Petersburg, the first serious political protests since Putin had taken office. We wanted to show the people of Russia that resistance was possible, and to spread the message that giving up liberty in exchange for stability was a false choice.

Unfortunately, Putin, like other modern autocrats, had, and still has, an advantage the Soviet leadership could never have dreamed of: deep economic and political engagement with the free world. Decades of trade have created tremendous wealth that dictatorships like Russia and China have used to build sophisticated authoritarian infrastructures inside the country and to apply pressure in foreign policy. The naïve idea was that the free world would use economic and social ties to gradually liberalize authoritarian states.

In practice, the authoritarian states have abused this access and economic interdependency to spread their corruption and fuel repression at home. To take one easy example: Europe gets a third of its energy from Russia in total, though some individual countries get considerably more. Meanwhile, Europe draws 80 percent of Russia’s energy exports, so who has the greater leverage in this relationship?

And yet for the last eight years since the Ukraine crisis began we have heard it repeated constantly that Europe cannot act against Russia because of energy dependency! Eight months after Putin annexed Crimea and three and a half months after evidence mounted that Russian forces had shot down a commercial airliner over Ukraine, Europe was still “considering” looking at ways to substitute Russian gas. Instead of using the European Union’s overwhelming economic influence to deter Putin’s aggression, they feign helplessness.

An EU boycott, or even a hefty tax, on Russian energy imports would threaten to completely destroy the Russian economy, which is now entirely dependent on the energy sector to stay afloat. But Europe lacks the political will to make significant sacrifices in the short run to meet the far greater long-term threat that an unchallenged Putin represents to global security and, by extension, to their economies dependent on globalization.

Engagement also provides modern authoritarian regimes with more subtle tools for escaping censure. They have their initial public offerings (IPOs) and luxury real estate in New York City and London, providing fees and tax revenue that greedy Western politicians and corporations are loath to give up in the name of human rights.

Unfree states exploit the openness of the free world by hiring lobbyists, spreading propaganda in the media, and contributing heavily to politicians, political parties, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). There is very little backlash when these activities are exposed. Citizens in the free world occasionally show outrage when a sweatshop is exposed in the media, but in the end they care little for the social environment of the countries that produce their oil, clothing, and iPhones.

As Russian oligarchs spread their wealth and Putin’s political influence around the globe, Western companies returned the favor by investing in Russia. Energy giants like Shell and British Petroleum (BP) couldn’t wait to get a shot at Russia’s immense energy reserves and the long-dormant Russian marketplace was an irresistible target, no matter how many concessions were needed to make deals. Human rights in Russia were the least of Western corporations’ concerns.

Even after Western firms were repeatedly betrayed, cheated, and threatened by their Russian partners and kicked out of partnerships or the country, they came back looking for more like beaten dogs to an abusive master. The most remarkable example was BP CEO Robert Dudley fleeing Russia in 2008, when he was the CEO of a joint venture with a group of Russian billionaires. Harassed continually and afraid of arrest (and that he was being poisoned, according to one account), Dudley fled and went into hiding. And yet a few years later he was back in Russia for a photo op with Putin himself announcing an oil exploration deal with state-controlled oil company Rosneft!

And while foreign investment has made up some of Russia’s GDP growth — most was due to the huge rise in oil prices — little of it improved the lives of average Russians. Most of these new riches turned right around and ended up in Western banks and real estate in the name of Putin’s oligarch elite. So while our ever-evolving opposition movement made some progress in drawing attention to the undemocratic reality of Putin’s Russia, we were in a losing position from the start. The Kremlin’s domination of the mass media and ruthless persecution of all opposition in civil society made it impossible to build any lasting momentum.

Our mission was also sabotaged by democratic leaders embracing Putin on the world stage, providing him with the leadership credentials he so badly needed in the absence of valid elections in Russia. It is difficult to promote democratic reform when every television channel and every newspaper shows image after image of the leaders of the world’s most powerful democracies accepting a dictator as part of their family. It sends the message that either he isn’t really a dictator at all or that democracy and individual freedom are nothing more than the bargaining chips Putin and his ilk always say they are. In the end, it took the invasion of Ukraine to finally get the G7 (I always refused to call it the G8) to expel Putin’s Russia from the elite club of industrial democracies.

By 2008, when Putin lent the presidency to his shadow, Dmitry Medvedev, it should have been clear to all that Russian democracy was dead. The only other names on the ballot were the loyal opposition in their appointed roles: Gennady Zyuganov of the Communists and Vladimir Zhirinovsky, who has been playing the part of far-right extremist since 1991. Both served, and still serve, as harmless window dressing to provide the merest appearance of democracy.

And yet one democratic leader after another lined up to play along with the charade. George W. Bush phoned his new counterpart to offer congratulations. French president Nicolas Sarkozy warmly invited Medvedev to Paris. Similar encomiums were offered by the leaders of Germany, the United Kingdom, and too many others to list. This, despite the fact that the election had been boycotted by the main European election-monitoring body, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), to protest against restrictions imposed on observers.

Two months after Barack Obama was sworn in, he and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton launched a new foreign policy initiative to “reset” the United States’ relationship with Russia. And not in the realist way you might expect after Russia had invaded tiny Georgia just months earlier to establish independent enclaves that are still occupied by Russian troops today. No, this was an American charm offensive. (One complete with misspelled props — the infamous “Reset Button” Clinton presented to her Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov actually said “overcharge” in Russian, not “reset.”)

The Obama administration wanted to believe the youthful and cheery Medvedev was a reformer, a potential liberalizer who would change Putin’s course. You can call this naïveté from the early days of “hope and change” if you like, but incredibly, this policy of engagement continued long after it became clear Putin was still very much in charge and that his plan to turn Russia back into a police state was unchanged. Putin’s “Operation Medvedev” was a total victory. He gained four more years to further eliminate all domestic opposition while avoiding any consequences on the international front.

When Putin predictably returned to the president’s office in 2012 he barely bothered to evaluate his rivals, and he knew he would face no real opposition from other world leaders. And, also like all dictators, Putin grew bolder with every successful step. Dictators do not ask why before they take more power; they only ask why not. When Putin looked carefully at the way leaders like Merkel, Cameron, and Obama treated him, he never found any reason not to do exactly as he pleased. One needn’t be a student of history to recognize this pattern, nor to see how it led to war in Ukraine.

The complacency that set in among the nations of the free world after the Iron Curtain came down could not be easily shaken off to deal with someone like Vladimir Putin. He exploits engagement to his advantage while conceding nothing. For years, as the human rights situation in Russia steadily deteriorated, Western politicians and experts such as Condoleezza Rice and Henry Kissinger defended Western feebleness in confronting Putin by saying Russians were better off than in the days of the Soviet Union.

First off, a sarcastic congratulations to them for damning us with faint praise! But instead of making comparisons to the 1950s or the 1970s, what about to the 1990s? It is not difficult to improve on life under the totalitarian Communism of Stalin or Brezhnev, but what about life under Yeltsin? What about the destruction of every newborn democratic institution in Russia while the Rices and Kissingers of the world looked on?

If the human rights of the Soviet people and the political prisoners in the vast gulags mattered, and they mattered very much, to so many leaders and citizens of the free world, why do dissidents in the twenty-first century not deserve similar concern and respect? Effective policies are based on principles. Ronald Reagan would talk with his Soviet counterparts but, as Václav Havel once told me, Reagan would also toss the list of political prisoners on the table first!

In my first years as an activist I often said that Putin was a Russian problem for Russians to solve, but that he would soon be a regional problem and then a global problem if his ambitions were ignored. This regrettable transformation has come to pass and lives are being lost because of it. It is cold comfort to be told, “You were right!” It is even less comforting when so little is being done to halt Putin’s aggression even now.

What is the point of saying you should have listened and acted when you still aren’t listening or acting? The mantra of engagement, and of refusing to address the crimes of dictatorships — especially if they are important business partners — has become so entrenched in the last twenty years that even the invasion of a sovereign nation in Europe cannot break its hold.

The United States and the European Union levied sanctions against Russian officials and industries after the 2014 annexation of Crimea, but it was mostly too little and too late. They still refused to admit the need for condemning and isolating Russia as the dangerous rogue state Putin has turned it into. Western leaders refused to admit that evil still exists in this world and that it must be fought on absolute terms, not negotiated with.

Hopefully, with the brutal new invasion of Ukraine, the democracies of the twenty-first century will realize they need to be ready for this fight.