The black naturalist, astronomer, surveyor, and almanac-writer Benjamin Banneker took issue with Thomas Jefferson’s attitude toward “those of my complexion.”

-

Fall 2023

Volume68Issue7

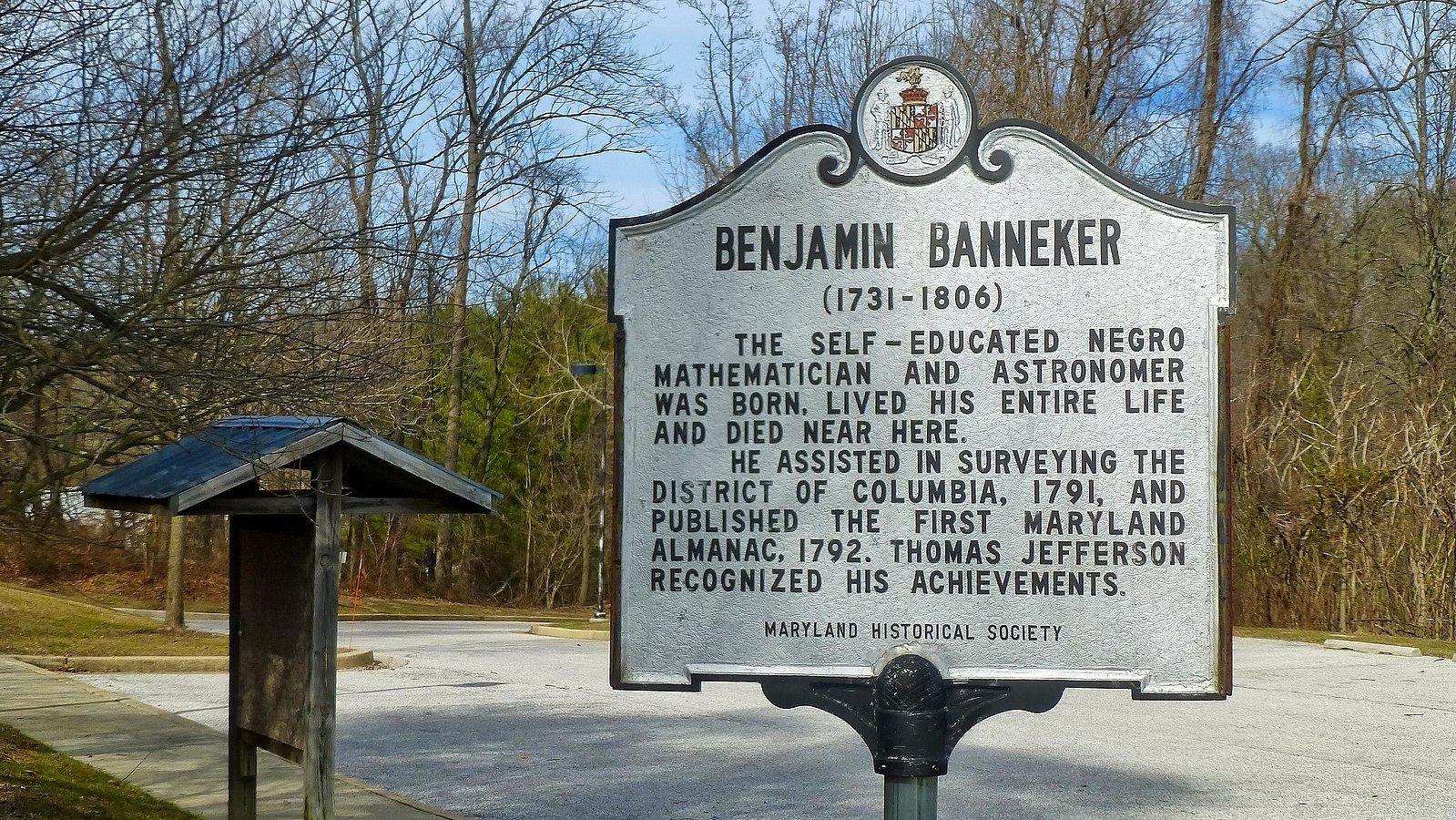

Editor’s Note: Benjamin Banneker was born free in 1731 in Baltimore County, Maryland in an environment in which abject deference to white people was not as deeply embedded as it was farther south. He was gifted in the sciences and became a naturalist and almanac-maker. In his 60th year, he wrote a letter to Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, challenging the famous espouser of liberty – and owner of over 200 slaves – to get beyond the doctrine of white supremacy and to support racial equality in the new nation.

Edward J. Larson is the author of seven books and won the Pulitzer Prize in History for Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion. His latest book is an important look at the twin strands of liberty and slavery in our nation’s founding, American Inheritance: Liberty and Slavery in the Birth of a Nation, 1765-1795, from which this essay was adapted.

“I am fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom which I take with you on the present occasion,” Benjamin Banneker wrote to Thomas Jefferson in August 1791, “when I reflect on that distinguished, and dignified station in which you stand; and the almost general prejudice and prepossession which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.”

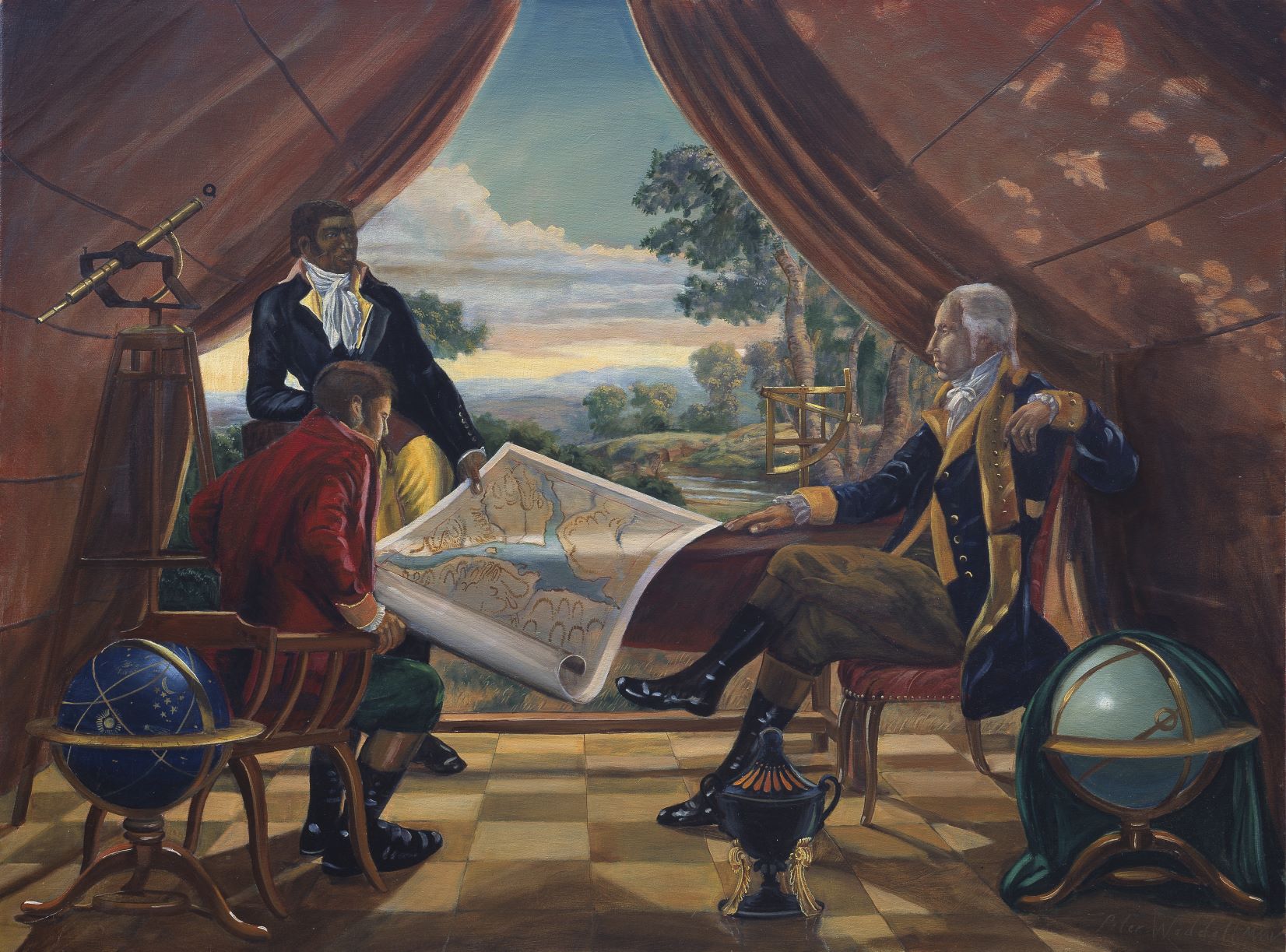

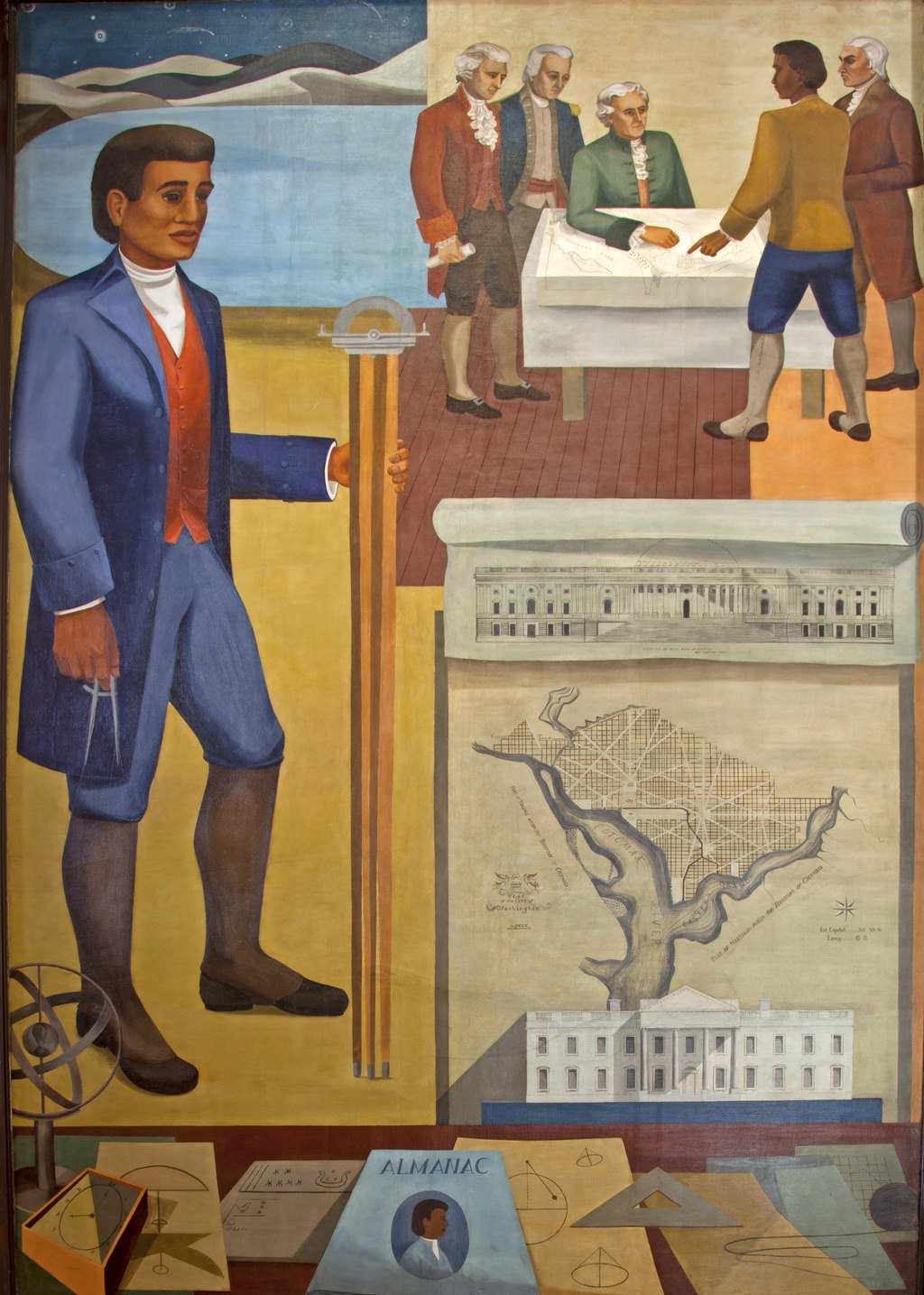

Jefferson was serving as America’s first secretary of state, with duties that included overseeing a boundary survey for the new federal district in Maryland and Virginia. Earlier in 1791, Banneker, a free black farmer and almanac-maker from rural Maryland, briefly assisted the Quaker land surveyor Andrew Ellicott with the federal district survey. Banneker lived near the Ellicott family gristmills, and Andrew Ellicott’s cousin had encouraged Banneker’s talent for computing the local times for future sunrises, sunsets, and other celestial phenomena.

When Banneker sent a table of his calculations for 1792 to Andrew Ellicott, who also made such ephemerides, Ellicott forwarded it to Pennsylvania Abolition Society president James Pemberton. He then shared it with Philadelphia astronomers and mathematicians as evidence of the reasoning ability of black people at a time when comparative anthropology was in its infancy.

The relative intellectual abilities of blacks and whites had emerged as an issue in the Revolutionary-era debates over slavery. In his 1776 Dialogue Concerning Slavery, the abolitionist-minded New England theologian Samuel Hopkins complained that white Americans viewed blacks as fit for slavery because “we,” as whites, “have been used to look on them not as our brethren, or in any degree on a level with us; but as quite another species of animals.” Slavery would end, he wrote, “if we could only divest ourselves of these strong prejudices, which have insensibly fixed on our minds, and consider (blacks) as, by nature, and by right, on a level with our brethren.”

By this time, some American supporters of slavery had begun to make the case for enslaving black people on supposedly scientific grounds, often drawing on the arguments of the Scottish philosopher and father of empiricism, David Hume: “I am apt to suspect the negroes, and in general all other species of men (for there are four or five different kinds) to be naturally inferior to the whites. There never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white, nor even an individual eminent either in action or speculation,” Hume wrote in a comment appended in 1753–54 to his xenophobic essay on nationality traits. “Such a uniform and constant difference could not happen, in so many countries and ages, if nature had not made an original distinction betwixt these breeds of men.”

Such reasoning flew in the face of traditional biblical beliefs of common descent from a divinely created first human pair, but that would not bother a religious skeptic like Hume. His pro-slavery American disciples embraced the same religious heresy to defend their enslavement of Africans, without relinquishing their commitment to liberty for those of their own kind, and with some going so far as to lump Blacks with apes and baboons as a single species of Africans.

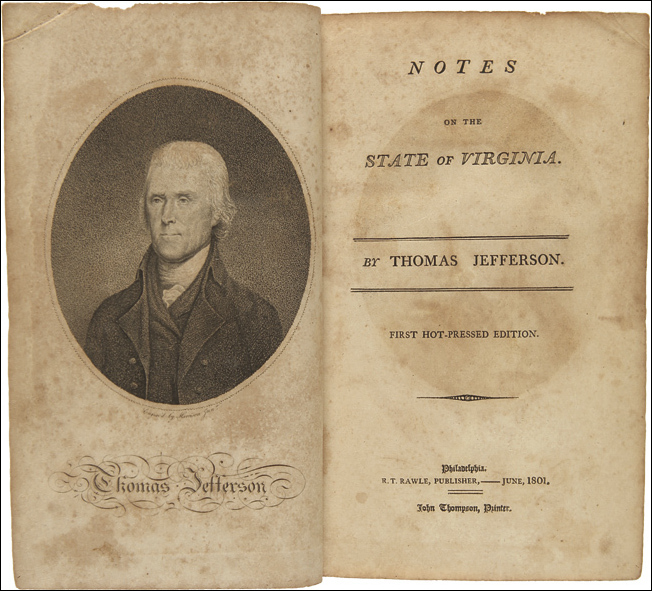

Following a long but specious recitation of the relative mental, emotional, and physical attributes of whites and blacks in his 1785 book Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson gingerly endorsed Hume’s implicit polygenism—the belief in the separate creation of the various races or species of people. “Comparing them by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me that in memory, (blacks) are equal to whites; in reason, much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination, they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous,” the author of the Declaration of Independence wrote. “Never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never saw even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture.”

A litany of such observations led to Jefferson’s suspicion that, paraphrasing Hume, “The blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites.” Slavery could not account for such differences because whites enslaved in ancient Rome, though held in conditions “much more deplorable than that of the blacks on the continent of America,” excelled in the arts and sciences, he noted.

Further, Jefferson added, some enslaved blacks “have been liberally educated.” This left race as the sole cause of the black condition.

Coming from a hero of the American Revolution, these widely read comments by Jefferson spurred abolitionists on a search for black intellectual exceptionalism. They could not leave his views of inborn black inequality unchallenged if they hoped to end slavery. If they could refute them, however, they felt that the logic of the proclaimed truths of human equality and the right of “all men” to liberty in Jefferson’s most famous treatise assured their eventual success. “If these solemn truths,” New Jersey abolitionist David Cooper wrote in 1783, “are self-evident: unless (they) can shew that the African race are not men, words can hardly express the amazement which naturally arises on reflecting that the very people who make these pompous declarations are slave-holders.” Abolitionists had Jefferson’s polygenism in their crosshairs.

Princeton theologian Samuel Stanhope Smith, a critic of slaveholding, took aim at polygenism in a 1787 address to Philadelphia’s American Philosophical Society published under the title An Essay on the Causes of Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species. Marshalling far more observations of human types than Jefferson ever mustered, Smith defended the biblical “doctrine of one race” by arguing that skin color and other racial traits derive solely from environmental causes, primarily heat and sunlight, with black being “the tropical hue.”

Moreover, these superficial traits remain mutable. Africans removed to a temperate climate already exhibited some physical transition, Smith claimed, with those who were fed well and living in humane conditions changing the most. “Mental capacity,” he stressed, “which is as various as climate and as personal appearance, is, equally with the latter, susceptible of improvement, from similar causes.” Smith’s environmentalism, if accepted, demolished the scientific case for race-based slavery.

Opponents of slavery had long touted the enslaved Boston poet Phillis Wheatley as an example of black literary ability, but Jefferson, in his Notes on the State of Virginia, had preemptively dismissed her from consideration as a counter-example to his argument. “Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Wheatley; but it could not produce a poet,” he sneered. “The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism.” Similarly, in an earlier dismissal of Wheatley’s genius, a British West Indian white living in Philadelphia scoffed at abolitionist Benjamin Rush for citing “a single example of a negro girl writing a few silly poems, to prove that the blacks are not deficient to whites in understanding.”

In a seeming response to the 1788 publication of Jefferson’s book in Philadelphia, Rush offered two fresh testimonials of black “mental improvement” at a meeting of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. One reported on James Derham, a freed black physician from New Orleans whom Rush hailed as “well acquainted with the healing arts;” another told of Thomas Fuller, an enslaved black with what Rush called “a talent for mathematical calculation,” such as quickly computing in his head “how many seconds there are in a year and a half.”

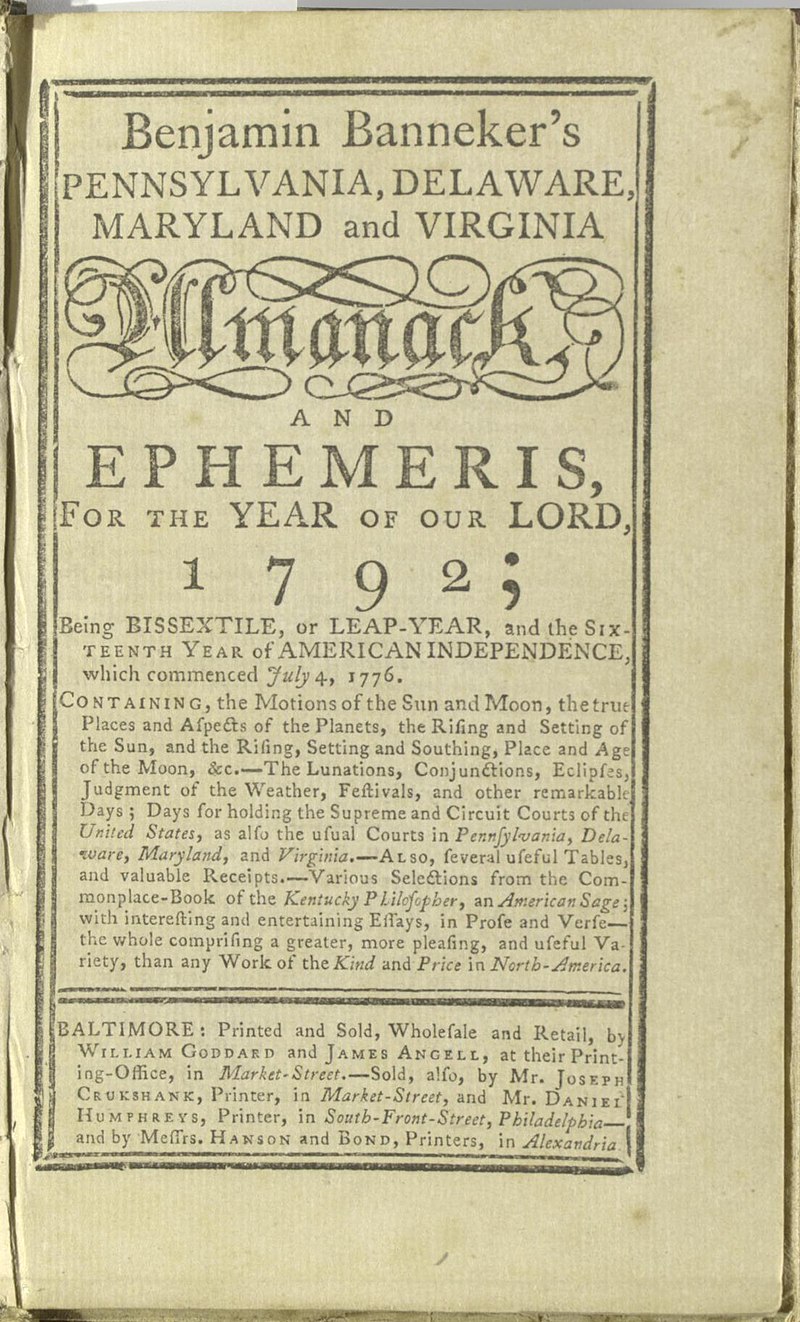

With the first publication of his astronomical calculations in an almanac of 1792, Benjamin Banneker became the American abolition movement’s prime example of native black intellectual ability. His distinctive attribute involved the skill and inclination to compute the future local time for regular celestial phenomena — that is, those caused by the cyclical motion of the moon and planets as observed from a particular place on Earth, which daily rotated on a tilted axis and annually revolved in an ellipse around the sun. Isaac Newton had established the science of those motions a century earlier, and some people enjoyed making the calculations for various locales.

Like any mathematical computations, making these tables took skill but, at a time when people relied almost exclusively on the sun and moon for light, and farming and fishing remained principal vocations, these specific calculations had practical value. Farmers used them to plant and harvest crops, travelers used them for planning night-time trips, and (because tides rise and fall with the gravitational pull of the sun and moon) navigators sailing or fishing in oceans and bays relied on them for safety and success. The local time for the rising and setting of the sun and moon, tides, eclipses, and the like varied over the year, based on the observer’s longitude and latitude, with people typically accessing the information in tables published in annual almanacs keyed to particular locales. Benjamin Franklin had published a widely read annual almanac, Poor Richard’s, from 1732 until he moved to London in 1757. The immediately popular New England almanac, Farmer’s (later Old Farmer’s), first appeared in 1792, with new annual editions ever since.

That same year, with support from local white abolitionists and at the urging of Andrew Ellicott, Benjamin Banneker published his first almanac at age sixty. Ellicott also suggested that Banneker send an advance copy to Jefferson as an example of a Black person’s faculty of reason. How much local abolitionists helped with the overall almanac, which included various articles and general information, remains unclear, but they gave credit for the calculation of celestial and tidal phenomena to Banneker. In the introduction to the first edition, the editors of Banneker’s Almanack hailed it as “an extraordinary Effort of Genius by a sable Descendant of Africa, who, by this Specimen of Ingenuity, evinces, to Demonstration, that mental Powers and Endowments are not the exclusive Excellence of white People.”

This preface included testimony to the accuracy of Banneker’s calculations from the Philadelphia scientific instrument-maker David Rittenhouse, hailed by Jefferson in his Notes on the State of Virginia as a “genius” and “second to no astronomer living.”

“Every Instance of Genius amongst the Negroes is worthy of attention,” Rittenhouse wrote at the time, “because their oppressors seem to lay great stress on their supposed inferior mental abilities.”

In a further prefatory endorsement testifying to the ephemeris as “exclusively and peculiarly” the work of Benjamin Banneker, federalist officeholder and former Constitutional Convention delegate James McHenry addressed the issue of polygenism: “I consider this Negro as fresh proof that the powers of the mind are disconnected to the color of the skin,” he wrote.

As more such instances of Black attainment emerge, as they must with the amelioration and “final extinction” of slavery, McHenry declared, “the system that would assign to these degraded blacks an origin different from the whites must be relinquished.”

The manuscript of his almanac completed by August 1791, Banneker sent a handwritten copy to Secretary of State Jefferson with a cover letter making his case for the right of blacks to liberty: “We are a race of Beings who have long labored under the abuse and censure of the world,” he wrote, and “have long been considered rather as brutish than human, and Scarcely capable of mental endowments.” Having heard “that you are a man far less inflexible in Sentiments of this nature, than many others,” he addressed Jefferson with a mix of deference and assertiveness, “I apprehend you will readily embrace every opportunity to eradicate that train of absurd and false opinions which so generally prevails with respect to us.”

Banneker offered his almanac as evidence of the reasoning faculty of Black people. Such work by a member of “the African race,” he declared, “and in that color of the deepest dye,” should show “that one universal Father hath given being to us all and endued us all with the same faculties.” Noting that his father came to America as “a Slave from Africa,” Banneker wrote about Blacks and whites in the United States, “However variable we may be in Society or religion, however diversifyed in Situation or color, we are all of the Same Family.” We are all Americans, he as much as said, and I am as much an American as you are.

In his letter to Jefferson, Banneker then made his case for American liberty and against American slavery: “Sir,” he began respectfully, “Suffer me to recall to your mind that time in which the Arms and tyranny of the British Crown were exerted with every powerful effort in order to reduce you to a State of Servitude.” He continued, “This Sir, was a time in which you clearly saw into the injustice of a State of Slavery, and publickly held forth this true and invaluable doctrine, which is worthy to be recorded and remember’d in all Succeeding ages. ‘We hold these truths to be Self-evident, that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happyness.'”

The naturalist and almanac writer from Maryland continued: “You were then impressed with proper ideas of the great valuation of liberty, and the free possession of those blessings to which you were entitled by nature.” Banneker went on without any pretext of deference: Yet, “at the Same time,” white people persisted “in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression” and remained “guilty of that most criminal act, which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.”

Banneker closed this portion of his letter with an admonition drawn from the biblical Job: ‘Put your Souls in their Souls stead," he implored Jefferson regarding his own enslaved Blacks. “Thus shall your heart be enlarged with kindness and benevolence toward them, and thus shall you need neither the direction of myself or others in what manner to proceed herein.” Banneker made his case for liberty to a white America still enthralled with black slavery.

Within ten days of receiving Banneker’s letter, Jefferson replied with a courteous four-sentence note. “No body wishes more than I do to see proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colors of men,” he wrote with measured ambiguity. The Virginia plantation owner then added, with respect to Banneker’s Almanack, “I consider it as a document to which your whole color had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them.”

Abolitionists promptly published this exchange, but it did not alter Jefferson’s behavior. He persisted in holding people in slavery and, as president, defended state-sanctioned slavery. The supposedly scientific debate over monogenism (the common ancestry of all peoples) versus polygenism intensified in antebellum America with the spread of slavery in the South and Southwest and the rise of abolitionism in the North and Midwest. As a rule, anti-slavery scholars took one side; pro-slavery scholars took the other. Polarization over the issue reigned in American science as much as it did over slavery in American society.

When the matter of the geographical spread or containment of slavery again reached Congress with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which admitted Missouri as a slaveholding state, but otherwise barred slavery in federal territories north of the new state’s southern border, Jefferson called it “a fire bell in the night.” He warned, “A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritant will mark it deeper and deeper.”

With the enslavement of over 1.5 million black people in the American South by 1820, Jefferson wrote, “we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” The maintaining of slavery, Jefferson wrote, “certainly is the exclusive right of every state, which nothing in the Constitution has taken from them and given to the general government.” James Madison, too, had come around to this viewpoint, questioning in a letter to President James Monroe whether Congress had the authority to limit slavery in the territories, and clearly denying that it had the power to do so in any new state once it was admitted to the union.

Even as Jefferson and Madison persisted in proclaiming liberty throughout their long lives, their later words demonstrated their continued commitment to state-sanctioned slavery, including in new states carved out of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. As Jefferson put it, the Missouri Compromise sounded “the (death) knell of the Union.” After hearing of it, he wrote, “I regret that I am now to die in the belief that the useless sacrifice of themselves, by the generation of ’76, to acquire self-government and happiness to their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons” to bar slavery in future federal territories.

Madison expressed much the same sentiment by depicting the object of the Missouri Compromise as “very different from the welfare of the slaves,” but, rather, a partisan effort to divide “republicans of the North from those of the South, and making the former instrumental in giving the opponents of both an ascendency over the whole.” The term “republicans” referred to members of Madison’s splintering Democratic-Republican political party.

Agreeing with Jefferson that a republic based on liberty could not survive a sharp sectional divide over slavery, Abraham Lincoln, a leader among the grandchildren of the generation of ’76, and a worthy descendant of that liberty-extolling cohort, saw the prospects for union very differently from Jefferson. “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” he quoted from scripture in a speech launching his campaign for United States Senate from Illinois in 1858. “I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

Lincoln’s celebrated House Divided speech was his response to the 1857 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which Chief Justice Roger Taney asked, “Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States?” To answer this question, he added, “We must inquire who, at that time, were recognized as the people or citizens of a State.” In line with Jefferson’s exclusion of Black Americans from the protections of American liberty, Taney categorically concluded, “Neither the class or persons who had been imported as slaves, nor their descendants, whether they had become free or not, were then acknowledged as part of the people,” and so, he ruled, this fact remained. Blacks were not American citizens and Congress could not outlaw slavery anywhere.

At this point in American history, twenty-five out of thirty-one states, including every state outside the Northeast, barred all Blacks — free and enslaved — from voting.

As Abraham Lincoln predicted, the Union did survive the abolition of slavery. It took, however, a civil war to “become all one thing, or all the other.” The division echoed the refusal to “confederate” that North Carolina delegate William Davie had warned of in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention, that Patrick Henry had suggested in 1788 at the Virginia ratifying convention, and that South Carolina representative Thomas Tudor Tucker made explicit in his response to Congress receiving anti-slavery petitions in 1790.

Even though Lincoln had vowed to respect the constitutional right of states to maintain slavery where it already existed, the threat to slavery and its expansion posed by Lincoln’s election in 1860 led seven lower southern states to secede from the Union. When the new president enforced the principle enunciated at the founding by James Madison that state ratification of the Constitution was “in toto, and for ever,” by sending federal troops to stop the insurrection, four more states bolted the Union from April to June 1861.

Following a four-year civil war costing over 600,000 lives, liberty prevailed over slavery and, as Lincoln proclaimed after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, “This nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” To abolish slavery officially throughout the Union, as urged by Black abolitionist leaders such as Fredrick Douglass, Lincoln pushed the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution through Congress early in 1865, shortly before his assassination and the war’s end in April. His successor, Andrew Johnson, then helped to secure its ratification by warning of reprisals against former Confederate states that refused to join northern and western ones in approving it. The reconstructed Georgia state assembly supplied the final needed vote on December 6, 1865.

Chattel slavery ended everywhere as news spread of the amendment’s ratification. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified three years later, reversed the Dred Scott decision by providing that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” Then, in 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment barred states and the United States from denying citizens their right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In the decades to come, these high-sounding guarantees fell victim to low-minded court decisions, domestic terror, scientific racism, and the still-strong traditions of states’ rights and local authority.

The long shadow of slavery continued to undermine declarations of liberty and equality through the twentieth century and into our own. Liberty and slavery remain our conflicted American inheritance.