Congress debated a resolution to impeach Jefferson because of an appointment that Federalists thought suspicious — an early precedent that clarified Congressional roles in oversight.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

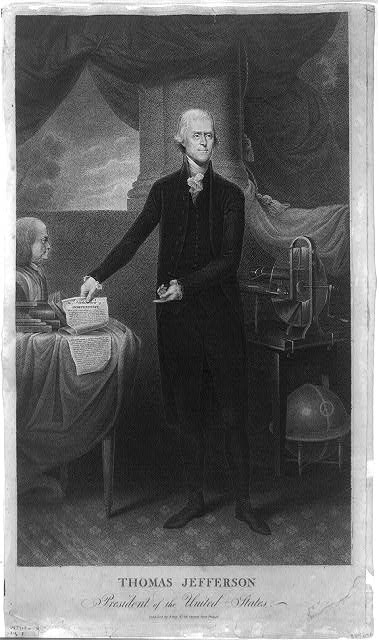

A survey of the administration of Thomas Jefferson, and indeed of the entire Virginia triumvirate, including Madison and Monroe, shows them to have been relatively free of proved instances of executive misconduct. Only one verified instance of corruption — that of James Wilkinson — mars the record, and its occurrence was not conclusively demonstrated until the twentieth century.

Charges of malfeasance, unconstitutional or illegal action, and duplicity were, of course, frequently lodged against these three presidents and against members of their official families. Furthermore, proved examples of misconduct and corruption in the lower echelons of the executive branch seem to have been somewhat more numerous. However, the record all in all was a good one.

Charges of corruption nevertheless abounded, principally because of the contemporary conception of corruption — which was taken to encompass not only personal depravity but also abuses of public and private power. These included executive removals from office, nomination by caucus, lobbying, and the partisan award of patronage. Contemporary charges of such kinds of purported misconduct have not been considered below, inasmuch as most were of a purely partisan nature and did not involve any suspicion of efforts to benefit high administration officials by criminal or clandestine means.

From 1800 to 1825, however, a subtle but important change occurred in both the charges and investigations of misconduct. Whereas in the early years of the century they generally concerned suspicion of assaults against the state, after 1815 they more frequently had to do with suspected wrongdoing in the interest of personal benefit or gain. By then, the government and its budget had become larger and more complex, Maneuvering for partisan advantage had become more open and competitive, and efforts to sniff out wrongdoing therefore more concerted. In addition, a democratic sensitivity to the exploitation of government for private ends had begun to spread. Inquiries into Burr's conspiracy and the controversy over the Two Million Act were thus characteristic of the early years.

Later the allegations of misuse of public funds lodged against Calhoun, Crawford, and Monroe were more representative. The canons by which allowable conduct was measured had broadened considerably by the 1820s. Office-bidders were now judged by their determination not only to protect the integrity of the government and the Union but also to protect the average citizen against being placed at a disadvantage in the competition for personal fortune by those who held or benefited from public office.

Attempted Impeachment

On January 25, 1809, Congressman Josiah Quincy, a Massachusetts Federalist, charged that a “high misdemeanor has been committed against this nation” by Thomas Jefferson. Seeking the Republican president’s impeachment, Quincy specifically charged that although Benjamin Lincoln, the collector of the Port of Boston, had for two years importuned Jefferson to allow him to resign for reasons of age and incapacity, Jefferson had refused to accept the resignation, hoping instead to preserve the lucrative post for his then secretary of war, Henry Dearborn of Massachusetts.

Quincy offered resolutions that Jefferson be requested to submit to the House all correspondence on the matter of the collectorship and that a committee of investigation be appointed. The House agreed, 93-24, to consider the resolutions.

In the ensuing debate it was argued, among other things, that Lincoln could resign, that Jefferson’s stance did not constitute a high misdemeanor, and that the House had no jurisdiction. The impeachment resolutions were overwhelmingly defeated, 117-1. Quincy’s attempt to embarrass the administration had failed, and the question was permanently dropped.

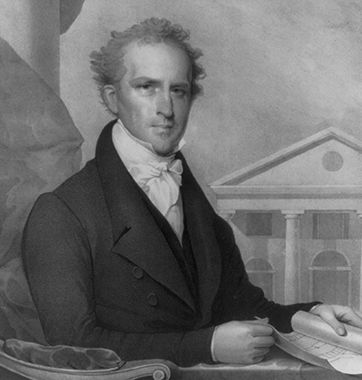

Dearborn, to whom Jefferson was committed, soon became collector of the Port of Boston. And the issue of appointments in the absence of statutes otherwise regulating tenures of office and the removal power (for alleged violations of which president Andrew Johnson was impeached and acquitted) seems never again to have arisen as a matter falling within the jurisdiction of the House to impeach.

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.