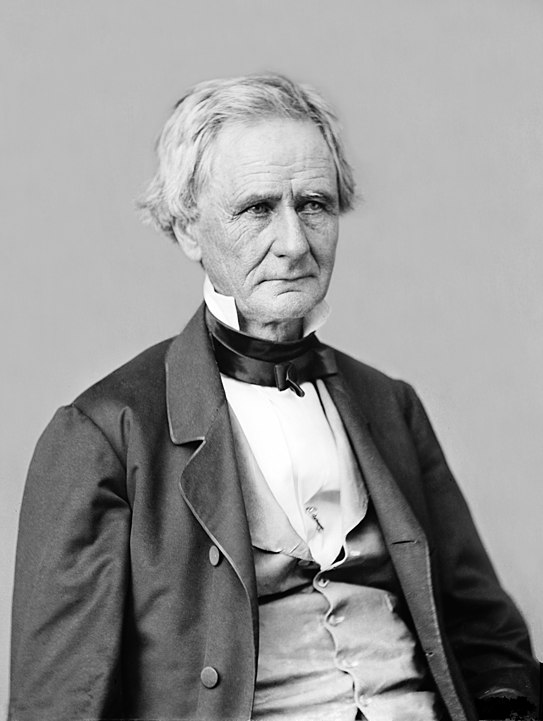

Lincoln's first Secretary of War amassed a fortune at the start of the Civil War, forcing a congressional investigation.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

There were instances of misconduct in Abraham Lincoln's administration, especially in the War Department and the army. And there were scandals, too, though none was ever linked to the president himself or to any member of his official family except for Simon Cameron, the first Secretary of War.

Historians regard much of the administrative irregularities as perhaps inevitable, given the chaos and confusion, waste and inefficiency, that characterized the Union war effort in the first two years of hostilities. In 1861, the government was almost totally unprepared to fight a massive civil war: it had never before had to raise, equip, and supply such large field armies; and it had never had to cope with problems of internal security at a time of domestic rebellion.

Lincoln himself, without previous administrative experience, thus confronted a national emergency for which precedents and guidelines were virtually non-existent. His cabinet members, moreover, lacked clear lines of authority in managing a war of this kind and often worked at cross-purposes.

From the outset, the Secretary of War Cameron was responsible for spending enormous sums of money to supply and equip Union armies. But the War Department was so understaffed that the Secretary turned to state governors and private citizens for help. The result was widespread chaos, as agents representing state governors as well as the Ordnance, Quartermaster, and Commissary Bureaus of the War Department vied with one another in spending federal funds for war materiel.

Apprised of certain irregularities in War Department spending, Congress in July, 1861, twice demanded that Cameron provide specific information on all government contracts awarded since March 4. But Cameron refused both times to comply. As a consequence, the House established a special committee on contracts to investigate; and the committee, after hearing testimony and examining war expenditures, produced a 1,109-page indictment of maladministration in Cameron's office.

The committee's principal complaint was that the Secretary and his maze of agents — some unscrupulous, others inept — had thrown competitive bidding to the winds and had bought exclusively from favorite middlemen and suppliers, many of them "unprincipled and dishonest." Thanks to a combination of inefficiency and fraud, the War Department had purchased huge quantities of rotten blankets, tainted pork, knapsacks that came unglued in the rain, uniforms that fell apart, discarded Austrian muskets, and hundreds of diseased and dying horses — all at exorbitant prices. In one instance, the War Department had sold a lot of condemned Hall carbines for a nominal sum, bought them back at $15 apiece, sold them at $3.50 apiece, and bought them back again at $22 apiece.

The list of abuses seemed endless. One Boston agent, charging the government a percentage of the contracts he arranged, made $20,000 in one week. Another agent acquired two boats for the War Department at a price of $100,000 each — after the navy had rejected them as unsafe—and one of the vessels sank on its first voyage. Then there were the activities of one of Cameron's own political lieutenants, Alexander Cummings, whom the Secretary had appointed as supervisor of army purchases in New York City. By Cummings's authority, the government spent $21,000 for straw hats and linen pantaloons and bought such "army supplies" as Scotch ale, selected herring, and barreled pickles. In addition, Cummings had contracted for 75,000 pairs of overpriced shoes from a firm that occasionally loaned him money.

The House committee, of course, bemoaned such "prostitution of public confidence to purposes of individual aggrandizement" and castigated Cameron's office for treating congressional law as "almost a dead letter," for awarding contracts "universally injurious to the government:' and for promoting favoritism and "colossal graft."

By January, 1862, Lincoln had decided that Cameron was not the man to run the War Department. While Cameron had not enriched himself in the contracts scandals, he was plainly an incompetent administrator. In addition, he too had violated Lincoln's policy regarding slaves and Negroes: without the president's approval, Cameron had released a War Department report in which he called for the enlistment of black soldiers, a move the President at this time officially opposed. In mid-January, when the Russian ministry became vacant, Lincoln appointed Cameron to fill it and named Edwin Stanton to head the War Department. In a private letter, however, Lincoln extolled Cameron for his "ability, patriotism, and fidelity to public trust."

Before leaving office, Cameron tried to defend himself: on January 15 he informed the Senate that he had never made "a single contract for any purpose whatever." At that, Representative Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts produced documents proving that all but 64,000 of 1,903,000 arms contracted for between August, 1861, and January, 1862, had been ordered under Cameron's direction. On April 30, 1862, the House censured him for entrusting men like Alexander Cummings with public money and for adopting a policy which damaged the public service.

In a message to Congress on May 26, 1862, Lincoln responded to the censure of Cameron, insisting that the president and all other department heads were "equally responsible with him for whatever error, wrong, or fault was committed in the premises." When war broke out, Lincoln explained, Congress was not in session, the capital was threatened with occupation, the nation was on the brink of disaster. Therefore Lincoln had met with his cabinet, and they had decided that they must assume broad emergency powers or let the government fall. Accordingly, the president had directed that Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles empower several individuals—including Welles's own brother-in-law—to forward troops and supplies to embattled Washington. The president had allowed Cameron to authorize Alexander Cummings and the governor of New York to transport troops and acquire supplies for the public defense.

Since the president believed that government departments were alive with disloyal persons, the president himself had chosen private citizens known for "their ability, loyalty, and patriotism" to spend public money without security, but without compensation either. Thus Lincoln had directed that Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase advance $2,000,000 to John A. Dix, George Opdyke, and Richard M. Blatchford of New York for the purpose of buying arms and making military preparations. All these emergency actions, the president stated, had received the unanimous approval of his cabinet.

Lincoln conceded that these measures were "without authority of law," but argued that they were absolutely necessary to save the government in the crisis that followed Fort Sumter. He did not deny that misdeeds had occurred in War Department operations, nor did he claim that the House censure was unjustifiable. But he was not willing, he said, to let that censure fall on Cameron alone.

Meanwhile, at Lincoln's urging, Stanton set about reorganizing the War Department, centralizing its activities, and conducting an official audit of its contracts. By canceling many of these and adjusting others, Stanton's auditors saved the government almost $17,000,000. At the same time, with the administration's full support, Congress enacted laws that required open and competitive bidding in government purchasing and that subjected contractors to court-martial in case of fraud.

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.