The presidency of Jimmy Carter was both shaped and bracketed by energy.

-

Winter 2025

Volume70Issue1

Editor's Note: Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of S&P Global, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, described by Business Week as hailed as “the best history of oil ever written.” More recently, he published The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations.

The presidency of Jimmy Carter was both shaped and bracketed by energy. Even before he took office, Carter made clear that he intended “energy” to be a linchpin of his administration. And it was – but not, as events turned out, in the way he had initially expected.

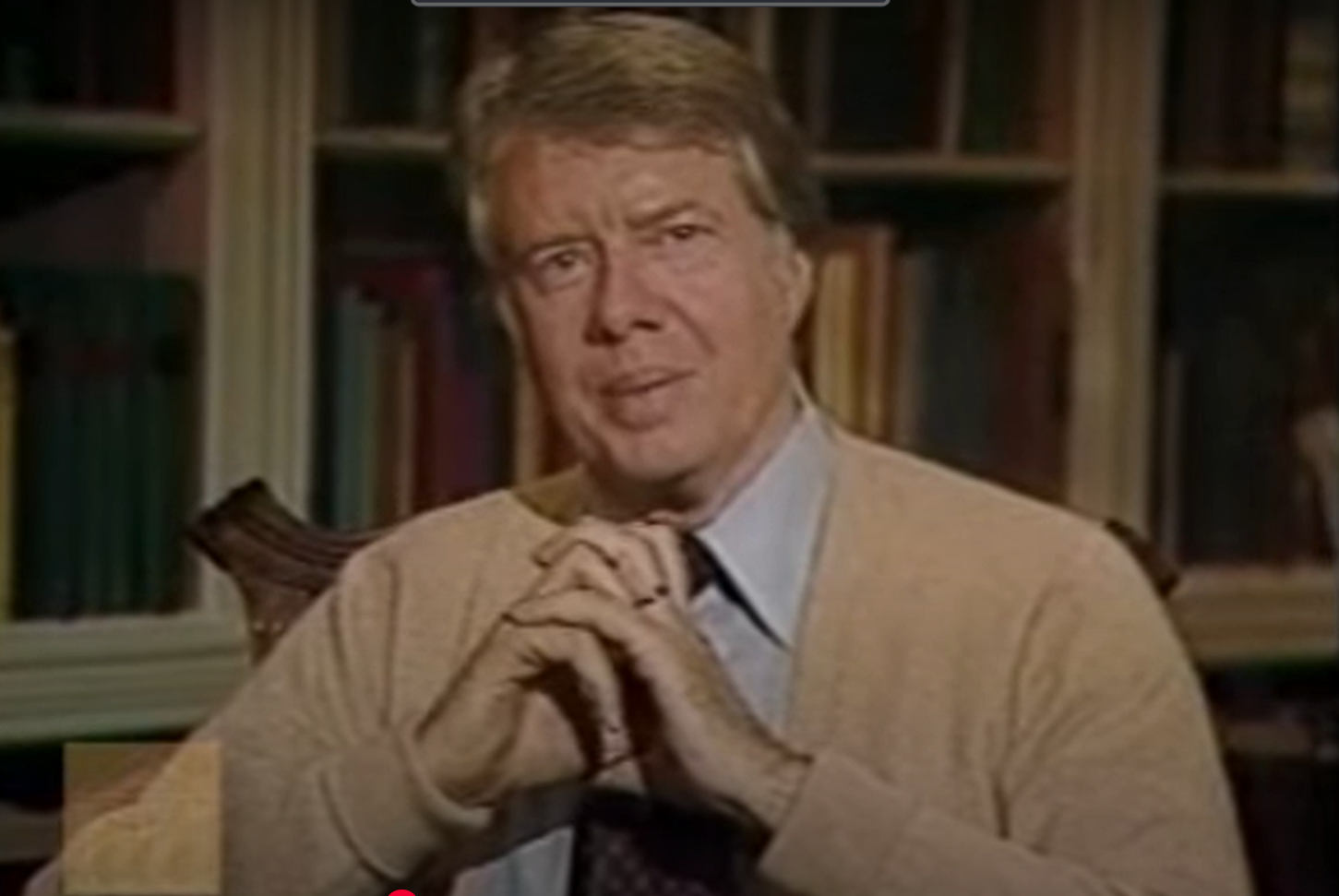

In early February 1977, just two weeks after becoming president, Carter, clad in a sweater, delivered what he called a “report to the American people”. He announced that energy would be the central focus of his administration. He ordered up a 90-day energy plan and went on to establish the Department of Energy. He followed up in April 1977 with a speech that began, “I want to have an unpleasant talk with you about a problem that is unprecedented in our history. With the exception of preventing war, he declared, “the energy crisis” was “the greatest challenge our country will face in our lifetime.” It was, he said, “the moral equivalent of war”.

Carter knew that the United States could not continue on the course of importing ever-more oil. The rapid growth of U.S. imports had helped set the stage for the 1973 oil crisis, just four years earlier, and for higher prices. He wanted to promote energy efficiency, renewable energy, and bring rationality to oil and gas prices, which were heavily distorted by an intricate and mindless system of price controls that made the nation’s energy situation more precarious – and more dependent on oil imports.

Making progress on energy policy faced much opposition and innumerable obstacles. Much of the opposition to ending the irrationality of price controls came from his own Democratic party. Still a good deal was accomplished, including the beginning of decontrol of oil and natural gas prices, although, as part of the political wrangling, matched up with a windfall profits tax. And Carter would succeed in establishing energy efficiency – conservation – as a key element in the overall approach to solving the nation’s energy problems – an initiative represented in a memorable conference that he convened at the White House. But his Secretary of Energy James Schlesinger would ruefully describe what had been achieved in response, as he put it, to Carter’s call to action as less than “the moral equivalent of war” and more like “the political equivalent of Chinese water torture.”

Carter was absolutely on target in trying to remove price controls, so that correct signals would flow to both consumers and producers. In other words, let the market work, let it promote investment and innovation, rather than having bureaucracy decide what prices should be. The natural gas shortages that had recently afflicted the country, forcing schools and factories to close, could be attributed directly to the price controls that discouraged investment in developing new supplies. Where Carter would be proved off-base was in his assertion that “the energy shortage is permanent.”

Yes, before his term was over, he would indeed confront a new energy shortage – but it was the result of what happened above ground, not below. It was external events in the Middle East that would change the course of his presidency.

September 1978 was one of the high points of Carter’s presidency and indeed marked an historic achievement, driven by Carter’s own will power and conviction. Sequestered at Camp David for almost two weeks with the president of Egypt and the prime minister of Israel, he hammered out an agreement that delivered what had been unthinkable – the framework for a peace agreement between Egypt and Israel – two countries that had been at war in one form or another since Israel’s founding in 1948. The Camp David Agreement was an extraordinary personal accomplishment by Carter.

This was truly an historic agreement that held out the promise of peace and stability in the Middle East after decades of war. But, even at that moment, another part of the Middle East was sliding into violence and chaos. This was the eruption of the Iranian Revolution. Iran was the world’s second largest exporter of oil. But, in the weeks just after Camp David, growing turmoil and strikes against the government of the Shah of Iran disrupted oil production, and then led to a complete halt in petroleum exports. The interruption of Iranian production was compounded by panic and a mad scramble for barrels that engulfed the global oil market. The protests and chaos across the country led to a seismic change not only for Iran but for the entire Middle East. The ruling Shah was forced to flee the country in January 1979 eventually to be succeeded by the theocratic regime of the Ayatollah Khomeini, who had returned from exile.

Energy had now become a crisis for Jimmy Carter’s own presidency. Oil prices more than doubled, gas lines returned in the United States to the great ire of motorists, anger swept the country, and inflation surged. A frustrated Carter fired members of his Cabinet. So turbulent had emotions become that, in July 1979, Carter turned what was meant to be an energy speech into a something broader – a disquisition on what he called “a crisis of confidence” that, he said, was striking “at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will.” When it got down to specifics of soothing the national soul, however, it was back to energy – a six-point program to address the “energy crisis”, which he called a “clear and present danger to our country.”

In November 1979, the bad situation got much worse: Iranian zealots breached the U.S. embassy in Tehran and captured U.S. diplomats. “America Held Hostage” became the nightly message across the United States. Carter authorized a rescue mission in April 1980, but it came undone in in an isolated staging area in Iran dubbed Desert One. Half a year later, in November, Ronald Reagan defeated Carter in the 1980 Presidential election. Jimmy Carter was a one-term president. The Iranians released the hostages on the very day Carter left office.

Reagan completed the decontrol of oil prices. Supplies began to build up around the world, while demand sagged in response to higher prices and recession – and energy conservation. In 1986 oil prices collapsed.

The energy crisis was over, at least for the time being. But, by then, Jimmy Carter had been out of office for more than half a decade.