Strict codes of conduct marked the relationships of early American politicians, often leading to duels, brawls, and other—sometimes fatal—violence.

-

Spring 2011

Volume61Issue1

Nothing in his childhood in Gloucestershire’s quiet parish of Down Hatherley had prepared 43-year-old Button Gwinnett of Georgia for the fierce politics that he encountered after signing the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776. One rivalry would turn so bitter that it would cut short his promising career. Violence, sometimes lethal, was an integral part of the fabric of the early American political discourse.

Gwinnett’s problems began when the Continental Congress awarded a military commission he craved to his chief political rival, Lachlan McIntosh, “the handsomest man in Georgia.” The two men represented opposite sides in an intense power struggle. McIntosh belonged to the conservatives, who lived mostly in and around Savannah and had run things for a long time. Newcomers Gwinnett and his friends came from the back country and outlying coastal counties. Evidence of the Gwinnett group’s increasing political clout emerged when Georgia’s assembly tapped him to serve out Archibald Bulloch’s term after the governor died suddenly in 1777.

In pursuit of glory on the battlefield, Gwinnett organized an expedition against British-held St. Augustine and eastern Florida in a bid to secure Georgia’s southern border. General McIntosh forbade Continental Army troops from joining the venture, which ended in mortifying failure. McIntosh publicly blamed the fiasco on Gwinnett, which helped defeat his rival’s bid to win a full term as governor.

Gwinnett mustered enough friends in the legislature to win exoneration in an official inquiry. An angry McIntosh rose in the assembly and called his foe “a scoundrel and a lying rascal.” That characterization forced Gwinnett either to challenge McIntosh to a duel or to retire from public life as coward, no longer worthy to be considered a gentleman

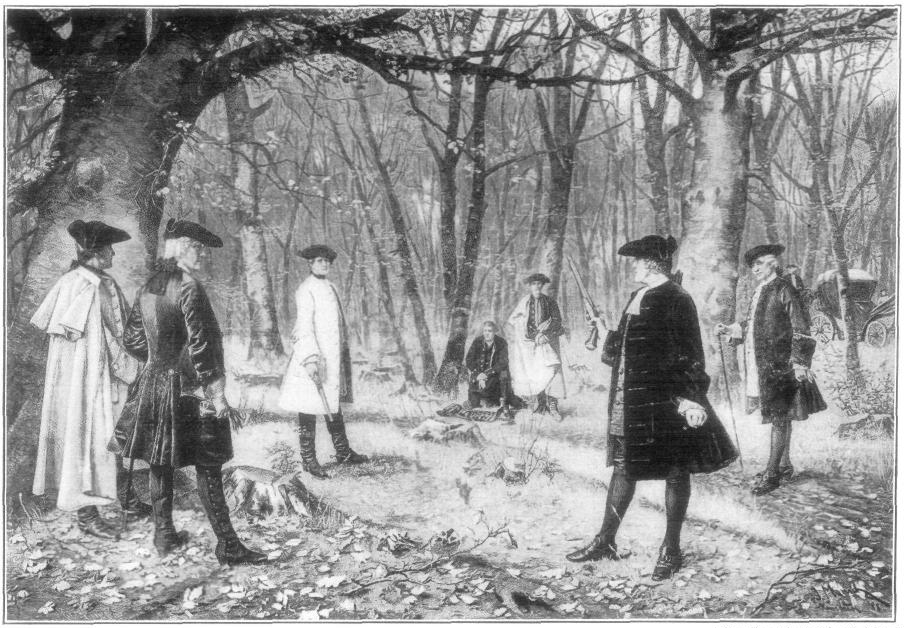

The antagonists met early on the morning of May 16, 1777, at a field a few miles outside Savannah. The principals and their seconds “saluted each other” with exceeding politeness, then examined the pistols to ensure they contained “only single balls.” They agreed to fire at 12 paces and lined up. On a signal from one of the seconds, both parties fired: an instant later, Gwinnett lay writhing with a shattered leg, his own bullet having left McIntosh with only a flesh wound. A few days later, Gwinnett died in agony from gangrene, leaving his widow and three children virtually penniless.

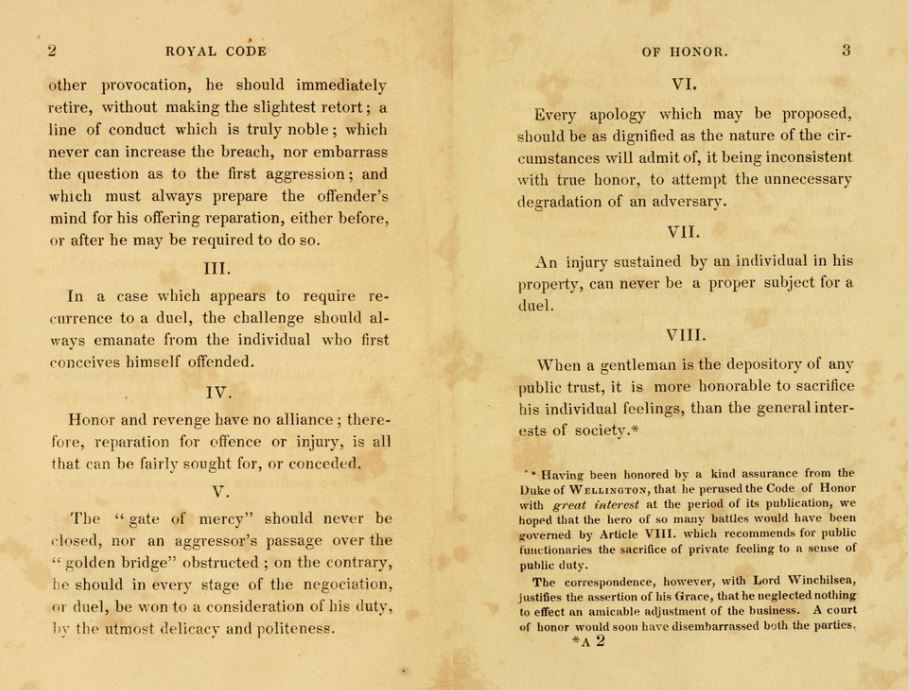

Gwinnett’s death was only the latest in a century of private violence over public causes. The political duel had originated in Europe, where it became common in the 17th century. No less an authority than the great English lexicographer and moral philosopher Samuel Johnson thought the tradition deplorable but necessary. If a man saw his reputation being murdered, Johnson said, surely he had a right to defend it by asking the killer to risk his life or apologize. Thus a duel was “essentially self-defense.”

Deeply embedded in this reasoning was the code of the gentleman, which held a man’s “honor” more sacred to him than life itself. Many saw politics as the pursuit of public honor, so a duel—whether occasioned by wounding words or by an insulting blow from a fist or stick—seemed a logical, even desirable, outcome, infinitely swifter and more decisive than a war of words in newspapers or resort to the law.

The above 1828 broadside, by Republican editor John Bins, skewered Jackson not only for the lives he took in defense of his honor but also for his controversial decision to execute six militiamen under his command during the 1813-1814 Creek War.

Dueling and politics became intermingled for another, less well-known reason: a surprisingly large number of combatants walked away unscathed. Only one in five duelists was killed (one study has estimated the death rate at only one in 14). The pistols of the day were not “rifled,” so they proved quite inaccurate even at close range. In addition, many seconds managed to negotiate a settlement before the duel took place.

During the Revolutionary War, most face-offs in America occurred between military men, who were hypersensitive about their honor and eager to display their courage. But once national politics began in earnest after the Constitutional Convention, the duel swiftly became the province of politicians. President George Washington turned up the heat of political partisanship because he had grown disgusted at the way the Continental Congress had left the nation a bankrupt, disunited mess after 15 years in power—and he was determined to make the new government serious and responsible.

He swiftly asserted his authority by telling European states to direct any communications to the president, not Congress. He waited until the legislative branch recessed to proclaim neutrality in the war between Britain and revolutionary France. Simultaneously, his secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton, proposed a formidable agenda, which included establishing a Bank of the United States, federal taxes, and the assumption of the Revolutionary War debts.

Opposed to what they deemed excessive federal and executive power, Thomas Jefferson and others denounced what they saw as a monarchy in the making. Soon two political parties—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans—were filling the political atmosphere with incendiary vitriol. The increasingly heated rhetoric touched off numerous duels.

This last phenomenon had a geographic dimension to it. The New England states were virtually duel-free because they had banned the practice in the 1720s. Harsh enforcement had created public peace. The South was at the opposite extreme, Charleston and Savannah being especially notable for bloody and often trivially personal pursuits of dignity. Some blamed the violence on the climate, others on a regional preoccupation with a type of chivalry that had run amok.

In the Middle Atlantic states, dueling was almost exclusively political, as the two parties wrestled for a supremacy that was as much individual as electoral. The hot-headed Hamilton waded deeply into New York’s war of words. In 1795, as he addressed a group of Manhattanites protesting President Washington’s refusal to support revolutionary France, a rock struck him in the head. Someone shouted that he was “an abettor of Tories” and a coward who had once refused a duel. Hamilton promptly challenged the man, and both vowed to fight as soon as possible. A few minutes later, another group of Francophiles began taunting Hamilton, who offered to shoot it out with each of them, one by one. Fortunately, his friends took care of these by now ridiculous acrimonies.

The election of Jefferson as president only further embittered many New York politicians. When lawyer George Eacker gave a Fourth of July speech hailing the new president as the savior of the Constitution from Federalist intrigue, Hamilton’s 19-year-year old son, Philip, and a friend called Eacker a liar and a fake. The lawyer called the youngsters “damned rascals,” whereupon both promptly challenged him.

Eacker fought Philip’s friend first; neither was hit. Hamilton advised his son to let Eacker take the first shot, then fire in the air. This tactic, known as the delope, not only aborted the duel but also implied that the delope was morally superior. Alas, Eacker killed Philip before he could make his gesture, leaving Hamilton and his wife distraught—and laying the groundwork for the most famous duel in American history.

Both Hamilton and Vice President Aaron Burr saw themselves competing for a higher level of fame than either had yet achieved. When Jefferson dropped Burr as his vice president in his second campaign, Burr ran for governor of New York with some Federalist support. Many thought that his election would help launch a third party of moderate Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Hamilton denounced Burr in one speech. But his influence had waned, and the Federalists ignored his comments altogether.

Burr lost in a landslide, which plunged him into a depression. Because he was already deeply in debt, the collapse of his political career meant financial as well as social ruin. In desperation, he challenged Hamilton over a remark in that single speech.

Both men understood the challenge’s symbolic importance. Many feared that a civil war was brewing: the New England states were threatening to secede over Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana territory. A man who refused a challenge would never command the army that could restore the Union. Both Burr and Hamilton were keenly aware as well that the young nation would need strong military leadership, with Napoleon Bonaparte rattling his saber in Europe. Should Napoleon succeed in his planned invasion of England, chances remained high that he might then send a large army to America and try to regain Louisiana by force.

So, the two formidable but somewhat tarnished political warriors met in Weehawken, New Jersey, on July 11, 1804. The evening before, Hamilton declared his intension to let Burr have the first shot and resort to the delope, perhaps to expiate the advice he had given his son—or to humiliate Burr into political extinction. Whatever his motive, the tactic proved fatal. Burr mortally wounded Hamilton with his first shot.

In the fallen Gwinnett’s Georgia, dueling had gained impetus from one of the nation’s first and greatest political scandals, the Yazoo lands imbroglio. Georgia legislators had sold millions of acres along the Yazoo River at low prices to real estate speculators, who then sold the land to investors all over the country, making huge profits. It turned out that Georgia did not even own this land in the first place. Senator James Jackson spearheaded a movement challenging the fraudsters, which eventually led the state legislature to try to revoke the sale. As a result, many speculators harbored violent thoughts about the slight Jackson, whom they called “the pygmy general.”

One of these opponents, Robert Watkins, met Jackson on the street in Augusta and accused him of heading “a damned venal set or faction which has disgraced their country [Georgia].” Jackson smashed him in the face with his cane; Watkins drew blood with a blow to Jackson’s head. Jackson pulled out a pistol and fired point blank, but someone struck up his hand. In a wild wrestling match, Watkins got on top of Jackson and tried to gouge out his eyes with his thumbs. Jackson bit Watkins’s fingers; he rolled away screaming, producing a pistol with a small bayonet on it and stabbing Jackson, missing his heart by inches. At this point friends dragged them apart, but both vowed eternal enmity.

Several more exchanges of insults drew a formal challenge from Jackson in 1802. The two men each fired four shots with no hits, but a fifth exchange sent a bullet through Jackson’s body just above his right hip. Swaying on his feet, he insisted he could manage another shot. But Watkins said he was satisfied, and the two men shook hands with the greatest cordiality, declaring their enmity to be at an end.

The hot-tempered Jackson learned nothing from this close call, continuing to fight many more duels with anyone who challenged his opinions. While he served in the U.S. Senate, those who did not want to hear bullets whistle were careful not to anger him. When Senator DeWitt Clinton of New York heard Senator Jackson starting to speak about him in menacing tones, he hastily apologized for everything and anything he might have said recently. The violence spread to the House of Representatives, where behavior was less decorous than in the Senate.

On January 30, 1798, a hot-tempered Irish-born Jeffersonian, Matthew Lyon of Vermont, began exchanging insults with Federalist Roger Griswold of Connecticut, eventually spitting tobacco juice into Griswold’s face. Federalists tried to expel Lyon but could not muster a two-thirds majority; Griswold decided he would settle the matter in person.

Two weeks later, Griswold strolled over to Lyon as he sat writing letters at his desk, and began beating him on the head and shoulders with a yellow hickory cane. Lyon reeled over to a fireplace, seized a pair of tongs, and countered his attacker. Within minutes they were trying to strangle each other on the floor, while the speaker called for order and their respective partisans cheered. The combatants were finally separated, but the spectators were so inflamed that brawls broke out throughout the rest of the day. Griswold pronounced himself satisfied; Lyon avoided provoking him again.

The West was almost as dark and bloody a ground for duels as was the South. The best known pistoleer by far was Andrew Jackson of Tennessee. By the time he became president, Jackson had stood at 10 or 12 paces at least 13 times. Wags claimed that he “rattled like a bag of marbles” from all the bullets in his body. Fellow Tennessean Charles Dickinson provoked Jackson in 1806 by asserting that his wife had not been divorced before he married her. That charge cast Jackson as an adulterer, his beloved wife as a bigamist, and him as unelectable by the standards of the day.

Jackson challenged Dickinson, considered the best shot in Tennessee and possibly the whole nation. The antagonists met near a mill on the Red River in Kentucky. Jackson had decided that his only chance was to let Dickinson fire first, betting that the wound would not be mortal. Jackson arrived in a loose cloak that made it difficult to target a specific part of his anatomy. Nevertheless, Dickinson’s bullet smashed into Jackson’s chest and broke several ribs. Somehow Jackson stayed on his feet, took careful aim, and shot his trembling adversary dead. “If he had shot me through the brain, I still would have killed him,” Jackson later said.

Among Virginia’s most famous duelists was the tall, shrill John Randolph of Roanoke, whose hot temper, sharp wit, and extreme opinions made him a party of one on Capitol Hill. In his estimation, President John Adams was “a traitor,” Daniel Webster “a vile slanderer,” and Congressman Edward Livingston “the most contemptible and degraded of beings, whom no man ought to touch, unless with a pair of tongs.”

The House of Representatives infuriated Randolph when it elected John Quincy Adams president in 1824. When Adams had failed to pull in a majority of the popular vote, he had made a backroom deal with candidate Henry Clay of Kentucky, who ordered his supporters to back Adams. In exchange Clay became Adam’s secretary of state. This “corrupt bargain” brought down torrents of abuse upon Clay’s head. In one overheated debate, Randolph called the political partnership a combination of “the Puritan and the blackleg.” The latter was a term for a cheat at cards, popularized by Henry Fielding’s novel Tom Jones. Everyone knew about the secretary of state’s fondness for late-night card games.

Clay called upon Randolph to apologize or fight. Randolph of course accepted pistols, and Clay’s friends feared the worst: Randolph was a dead shot. But the eccentric Virginian confessed to several friends that he did not want to kill Clay, who had a wife and child. It would have proved political suicide for Randolph. He intended to give Clay the first shot and then fire into the air. But Randolph testily added that he might change his mind if he saw “the devil” in Clay’s eyes.

On January 9, 1809, as they gathered on a field near Arlington, Virginia, Randolph saw ominous devilment in the infuriated secretary’s eyes and shot to kill. He put a bullet through his adversary’s coat. Clay’s bullet missed, and he demanded another round. Clay missed again. This time Randolph fired in the air. One eyewitness said that both men, after shaking hands, acknowledged their pleasure that no blood had been shed. Another version, probably more likely, was that Randolph told Clay that he owed him a new coat. Clay curtly replied: “I am glad the debt is no greater.”

When slavery became the issue of the day, deadly violence grew even more pronounced. In 1838 tempers flared when a New York newspaper accused Jonathan Cilley, an outspoken antislavery congressman from Maine, of corruption. Cilley retorted that it was the newspaper editor who was corrupt. Kentucky Congressman William Graves delivered a letter to Cilley on the newspaperman’s behalf, asking for an “explanation”—the usual prelude to a duel.

Cilley dismissed the letter, claiming that the editor was not a gentleman. Congressman Graves took offense, believing that Cilley’s actions implied that he too was not a gentleman. Graves demanded satisfaction. Cilley chose rifles, and the men exchanged two rounds at Bladensburg, Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C. None of the bullets found their mark. It appeared that the duel had ended in a draw.

But Henry A. Wise, Graves’s second and a fervent proslavery congressman from Virginia, persuaded them to go another round, and Cilley died instantly. National shock and outrage pushed Congress into banning duels in the District of Columbia.

Such legislation by no means kept Congress violence-free. As the years passed, rhetoric grew even more intemperate, reaching a climax of sorts during the ugly violence between proslavery and free-soil Kansas settlers in the 1850s. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts rose in the Senate in May 1856 to denounce the struggle, which he blamed on “hirelings picked from the spew and vomit of an uneasy civilization.”

Sumner proceeded to insult several Democratic senators. He was especially savage toward 59-year-old Senator Andrew Pickens Butler of South Carolina, who suffered from a speech impediment (and whom he had once regarded highly). Sumner implied that Butler personified South Carolina’s inferior society, where a man “cannot open his mouth but out there flies a blunder.” The mild-mannered Butler, who was not present, made no attempt to reply when he later heard about the invective. His nephew, Congressman Preston A. Brooks, however, decided that it was his duty to “relieve” his uncle and “avenge the insult to my state.”

Three days later, Brooks strolled into the nearly empty Senate chamber and found Sumner writing letters at his desk. “Mr. Sumner,” Brooks said. “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina and on Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.” Whereupon he smashed Sumner over the head with a heavy gutta-percha cane. Trapped behind his desk, Sumner could not escape the murderous blows. In desperation, he tore the desk out of its floor bolts, but another blow knocked him headlong. As he lay there, blood streaming from his head and face, Brooks continued to beat him until the cane snapped. It would take three years for Sumner to recuperate. Before a motion could be drafted for Brook’s expulsion, he coolly resigned and went home to South Carolina, where he was almost unanimously reelected a month later.

Tensions in Congress came to a boil in 1858, when President Buchanan asked it to admit Kansas as a slave state, an initiative backed by the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, which denied Congress the power to prohibit slavery in the territories. Intemperate shouting matches sometimes wracked the Capitol until dawn. Finally a South Carolina congressman told a Pennsylvanian that he was a “black Republican puppy.” He responded: “No Negro driver will crack his whip over me!”

At least 50 members began punching, kicking, shoving, and hurling obscenities. The sergeant at arms waved his mace, with its spread-winged eagle, and bellowed in vain for order. Representative John “Bowie-Knife” Potter of Wisconsin tried to seize William Barksdale of Mississippi by his hair, whereupon his entire scalp peeled away—the gentleman was wearing a wig. “I’ve scalped him!” howled the delighted Potter. Everyone stopped fighting to stare at the bald Barksdale, then erupted into laughter.

Beyond the walls of Congress, newspapers, other politicians, and the public had begun to ridicule the culture of violent politics. An early critic was Illinois politician Abraham Lincoln. As a state legislator, he had found fault with the work of the state auditor, James Shields, satirizing him in letters to newspapers. Shields challenged him to a duel, which he accepted. Lincoln, at least eight inches taller than Shields, chose cavalry broadswords as the weapons, in the belief that his challenger would retreat. Instead, Shields spiritedly consented. But when Shields showed up at the appointed place, he found Lincoln casually chopping branches off a nearby tree at a height that Shields could not reach without a stepladder, a practical demonstration that brought a breath of reason into the affair. Suddenly Shields was ready to talk rather than fight. Lincoln offered an apology for the “misunderstanding,” which Shields accepted with evident relief. Shields lived to become the only U.S. senator to serve three different states.

Thirty years later, a witty Southerner used this growing sense of the ridiculous to help put the quietus on the bloody pursuit of honor. During the Civil War, Mark Twain spent several years in Virginia City, Nevada, more or less hiding out in public to avoid service in the Confederate Army. In one of the many amusing editorials he wrote, he accused James Laird, publisher of a rival paper, of welshing on his promise to give money to a local charity. Laird responded so violently on paper that Twain felt forced to challenge him.

Escorting him to the dueling ground an hour early so he could practice his marksmanship, Twain’s second swiftly saw that his principal was a hopelessly awful shot. The second seized the gun and shot the head off a mud hen sitting on a nearby branch, leaving a starkly visible corpse for Laird and his second to ponder.

“Who did that?” asked Laird’s second with some alarm.

His opposite number pointed to Twain: “Take my advice. Don’t let Mr. Laird commit suicide.” After a hasty conference, Laird accepted Twain’s offer to shake hands. Later, Twain joked about his immense relief when the duel was called off, intoning in his best deadpan voice that he was now “inflexibly opposed to the dreadful custom” of dueling. “If a man were to challenge me now—now that I fully appreciate the iniquity of the practice—I would . . . take him by the hand, and lead him to a quiet retired room—and kill him.”

One writer has compared Twain’s ridicule to Cervantes’s satire of airhead knights such as Don Quixote, smothered in the rituals of a chivalric tradition long past its prime. It was a characteristically wry way of putting the political duel out of business once and for all.

Looking back on these decades of political mayhem, one can only conclude that many early American politicians were afflicted with a kind of public myopia. Until the 1840s the press hesitated to report violent political language and its often fatal outcome, unless the incidents involved national figures such as Hamilton and Burr. After the invention of the telegraph in 1844, violence in Congress began getting national attention. But it was the ultimate violence of the Civil War, with its 620,000 deaths, that shocked Americans into realizing that violent public words could become deadly on a terrifying scale. It is a lesson Americans should never forget.