A junior Army officer, acting on secret orders from the president, bluffed a far stronger Mexican force into conceding North America's westernmost province to the United States.

-

Winter 2011

Volume60Issue4

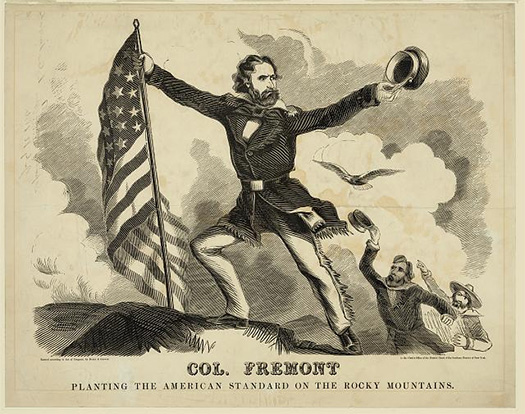

In June 1842, Army topographer Lieutenant John Charles Frémont and 22 men left Chouteau’s Trading Post near present-day Kansas City to survey a wagon trail that would lead through the northern Rockies to Oregon. By August, a small splinter group led by Frémont and his most famous scout, Kit Carson, snaked their way through the Wind River Mountains, determined to plant a flag on what was believed to be the continent’s highest peak.

After altitude-induced headaches and vomiting frustrated their first summit attempt, Frémont and the five he had selected for the final climb again launched the perilous trek through rocky gorges and defiles to a meadow above three glacier lakes, where they turned their mules loose to graze and began the last slow trudge toward the snow-capped summit, which would be named Fremont Peak.

He replaced his thick parfleche moccasins with a light pair “as now the use of our toes became necessary to a further advance.” An overhanging buttress blocked their way, forcing them to ascend a granite precipice. He leaped onto the narrow crest, nearly plunging 500 feet off the other side. As he caught his breath in that absolute stillness, a bumblebee appeared—or so the legend goes. “It was a strange place, the icy rock and the highest peak of the Rocky Mountains, for a lover of warm sunshine and flowers,” wrote Frémont. “We pleased ourselves with the idea that he was the first of his species to cross the mountain barrier—a solitary pioneer to foretell the advance of civilization.” They mounted their barometer on the summit and measured the altitude at 13,500 feet (which would turn out not to be the highest peak in the Rockies).

They fired their guns, broke open a bottle of brandy, and, thrusting a ramrod in a fissure, Frémont unfurled an unusual flag he had commissioned in New York City “to wave in the breeze where never flag waved before.” Emblazoned with 26 stars representing the number of American states and an eagle whose talons held an Indian peace pipe along with arrows, the banner claimed the farthest reaches of the continent for the United States.

“The Pathfinder,” as the press would soon dub him, would parlay the achievement into national celebrity. He presented his new wife, Jessie, with the unfortunate bee pressed into a book and the curious new flag that he had made himself, both symbols and manifestation of American expansion. Collaborating with his dynamic young wife, he turned his 215-page report to the War Department into an international best seller blending scientific details with salty frontier anecdotes. The characters—Kit Carson, Indians, mountain men, fur traders—came alive, crowding with human drama the landscape that Frémont had mapped and charted, turning the unshaven, rough-hewn explorers into heroes on a visionary quest. For the first time in American history, an explorer’s report offered a gripping narrative and the literary polish of the world’s classic adventure stories, with the leader’s exploits elevated to a par with such world-class figures as Captain Cook and Coronado.

While this first expedition fueled Frémont’s meteoric rise, it also signaled the beginning of a decades-long pattern in his life that was marked by moments of glory but punctuated by sustained defeats. This colorful and sometimes impulsive explorer is best known today as the first presidential candidate of the Republican Party and the first Union general to issue an emancipation proclamation during the Civil War. But ironically, his most significant nation-shaping role would be relegated to a mere footnote: his conquest of California—the plum of manifest destiny—would yield neither fame nor fortune. Instead it would earn him ignominious charges of mutiny and insubordination.

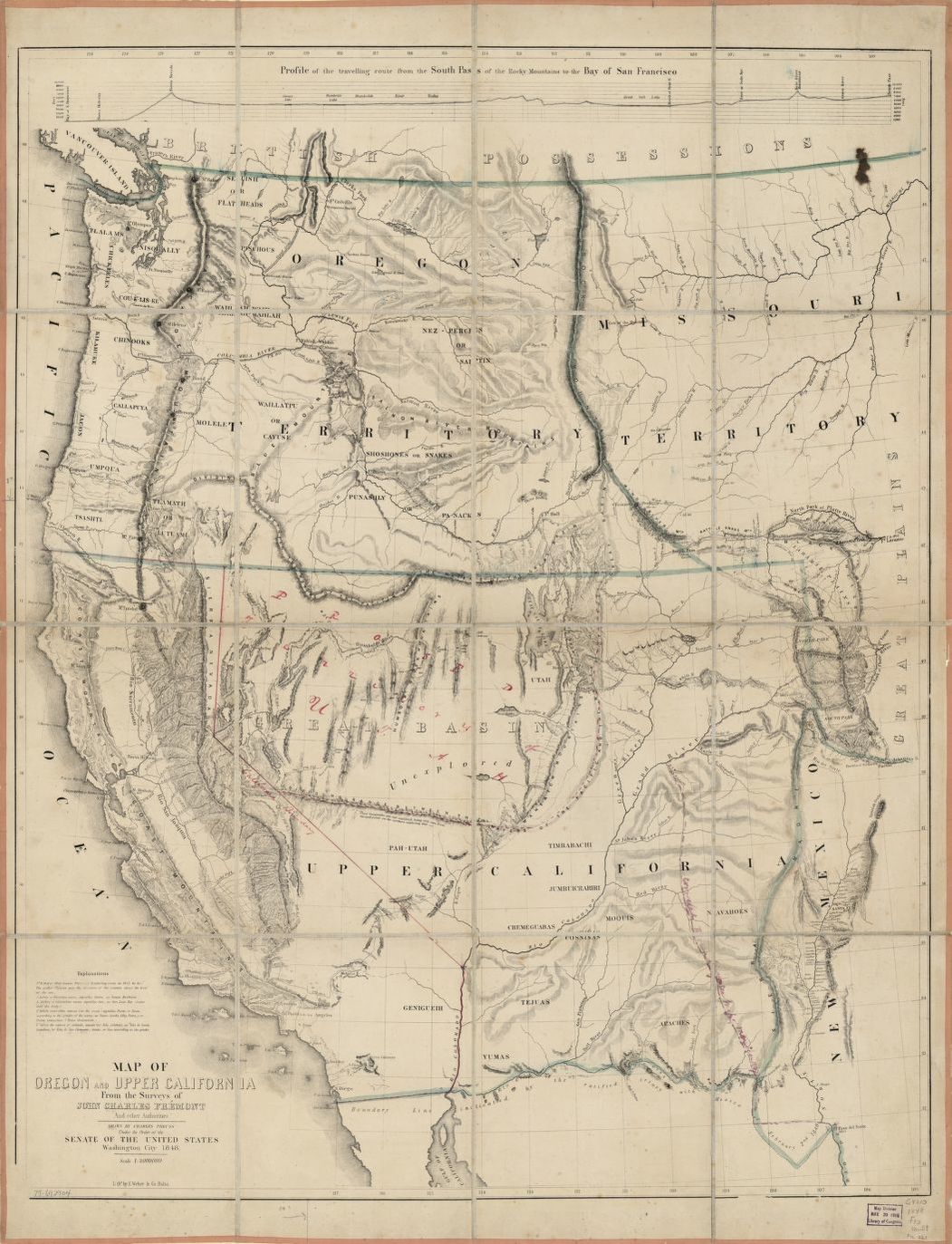

On March 1, 1845, upon returning from another exploratory trip to California, Frémont reported to the War Department that the continent could be traversed and then settled from sea to sea. His timing was auspicious. That day Congress voted to annex Texas, and rumors filled Washington of the likelihood of war with Mexico.

The future of Texas (even larger than it is today) and Oregon (then embracing the entire U.S. Pacific Northwest and a substantial part of Canada, all conjointly owned with Great Britain) had been at the forefront of political discussion for several years, straining relations with Mexico and the United Kingdom. A significant British naval force was patrolling the Pacific Coast, poised for what many thought would be an invasion of California, then under Mexico’s weak and over-stretched authority. The expansionists feared that the British would either seize California or join with Mexico in a war against the United States.

James Knox Polk, who took office as president three days after the Texas resolution, had won the election partly on the national fears of such a British invasion, and he made national expansion the cornerstone of his foreign policy. A storm of aggressive threats was loosed, setting the stage for Polk to take action, with Frémont a crucial player in his game. Within weeks of his inauguration, Polk summoned one of his closest advisers, the powerful Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, and Frémont, Benton’s protégé and son-in-law, to discuss the “Western problem”: they found Polk set on winning California. Frémont subsequently met several times with two of Polk’s cabinet—Secretary of State James Buchanan and Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft—who would ultimately dispatch him to California.

Buchanan, an enthusiastic proponent of annexing California, enlisted Frémont’s Spanish-speaking wife Jessie to translate diplomatic correspondence and Mexican press accounts. Equally focused on the Golden State, Bancroft urged Frémont to seize California when the opportunity arose, as the Pathfinder recalled it, but did not commit the orders to writing because of the delicacy of the political situation. Frémont knew that if he proved unsuccessful, the administration would unhesitatingly repudiate him. Meanwhile, as secret translator for both Buchanan and Polk, Jessie was aware both of Mexico’s California strategy and of the Far West foreign policy the president was formulating; the situation poised her as a unique go-between the administration and her husband.

Everyone seemed to want war: Mexico, enraged by the annexation of Texas; Great Britain, desirous of claiming a large part of Oregon; the United States, hungry for California. Polk and his cabinet were hoping to extract a favorable settlement from Mexico over the Texas boundary, while also maneuvering to acquire New Mexico and California. Polk had sent a confidential emissary to Mexico City prepared to offer as much as $40 million for the lands in question. But that agent, and a second one as well, would fail.

Working secretly, Polk, Benton, Buchanan, and Bancroft mapped out the course of a Frémont-led expedition that would ostensibly survey a trail west for American immigrants. If he received word that war had begun, Frémont was to continue into California and impede any British designs on San Francisco Bay. “California stood out as the chief subject in the impending war,” Frémont wrote much later, “. . . and with Mr. Benton and other governing men at Washington it became a firm resolve to hold it for the United States.”

The ultimate origin and actual details of Frémont’s orders, the covert nature of his mission, and the chain of command he was expected to follow remain murky and contradictory to this day. The official orders issued that spring made no mention of California and contained no direction of a military nature. A private conversation about the expedition between Benton and Polk would be recorded with frustrating vagueness in both men’s diaries and recollections, spawning conspiracy theories that endured into the next century.

On May 15, 1845, Frémont left Washington for St. Louis, where he found a strong contingent of troops and sailors assigned to his “survey.” Hundreds of volunteers soon came forward, clamoring to serve in the obviously far-destined column under so famous a commander. He chose 62 men—a diverse, tough outfit of frontiersmen, scientists, soldiers, sharpshooters, and hunters. He held a marksmanship contest, rewarding the winners with the finest weapons of the day. Each volunteer received a Hawken rifle, two pistols, a knife, a saddle, a bridle, two blankets, and a horse or mule. In late August the heavily armed party headed west with 200 horses and a dozen beef cattle. Unbeknownst to him, the president had received an alarming dispatch from the U.S. consul at Monterey, California, warning that Mexican troops, financed by Great Britain, were on their way north.

In response Polk secretly dispatched Lt. Archibald H. Gillespie, USMC, overland through Mexico and then by a naval warship to California with orders to Frémont, along with a sealed envelope from Jessie to John, which conveyed instructions from Bancroft in a family code known only to Frémont, Jessie, and her father. “As we had a squadron in the North Pacific, but no army, the measures for carrying out this design fell to the Navy Department,” wrote Bancroft 40 years later. “Frémont having been sent originally on a peaceful mission to the west by way of the Rocky Mountains, it had become necessary to give him warning of the new state of affairs and the designs of the President. . . . Being absolved from any duty as an explorer, Captain Frémont was left to his duty as an officer in the service of the United States, with the further authoritative knowledge that the government intended to take possession of California.”

Disguised as an ailing businessman seeking health in moderate climes, Gillespie memorized and destroyed the official documents. He also carried instructions from Buchanan to the consul urging that the Californians be encouraged to secede peacefully from Mexico and join the United States. The contents of this letter were so sensitive that it remained classified for the next four decades.

Jessie’s letter informed Frémont of the latest intelligence regarding the imminent war and of the president’s decision to overthrow Mexican authority in California. Benton also wrote a letter in the same code: “The time has come. England must not get a foothold. We must be first. Act; discreetly, but positively,” as Frémont later summarized it.

Bancroft ordered the commander of the Pacific squadron to seize Mexico once it had declared war on the United States. At the same time, General Zachary Taylor, in command of the Army of the Southwest, was proceeding toward Mexican territory. In October, after Polk’s emissary to Mexico reported excitedly that Great Britain intended to transport immigrants from famine-ravished Ireland to establish a colony in California, Bancroft sent new orders to the naval commander indicating that he need not wait for an official declaration of war. Camped by the Great Salt Lake, Frémont, wholly ignorant of these latest developments, focused on driving his men as quickly as possible over the Sierra Nevada to avoid its legendary deep snows.

Feeling no substantial attachment either to Mexico or the United States, the native Californians had no inspiration or incentive for revolution, which posed a dilemma for the Polk administration. Any chance of working with residents to ignite a local uprising seemed unlikely. By the time Frémont came over the mountains in December 1845, the Mexican governor had been ousted by an insurrection led by a native politico, José Castro. Castro installed himself in Monterey as military comandante and appointed his sidekick, Pío Pico, as civil governor to rule from Los Angeles, which they declared the capital. Castro and Pico soon vied for power, dividing California into northern and southern regions, which further weakened the ties to Mexico City and threatened civil war. Into this cauldron of intrigue rode Frémont’s column.

In full officer’s uniform, Frémont led his men into Sutter’s Fort on December 10, 1845. Named for its Swiss owner, who had received a large land grant from the previous governor, the fort and its extensive American settlement located near present-day Sacramento was viewed with suspicion by the Mexican authorities. Frémont, who had met John A. Sutter on a previous expedition, now wished to pay his respects and request much-needed supplies. Sutter was not there, however; his arrogant majordomo gave the new arrivals a cool reception and denied Frémont’s request for 16 pack mules, six saddles, and other goods. Frémont angrily withdrew.

The majordomo followed Frémont’s party to their camp, where he apologized and explained that tensions were mounting in California, and that Sutter, who had been on the losing side of the recent coup, was preoccupied with currying favor with both sides. Frémont grudgingly accepted the belated offer of provisions and the services of the fort’s blacksmith. When the notoriously slippery Sutter returned three days later, he promptly reported Frémont’s arrival to both the Mexican and American authorities.

Returning to the fort on January 15, with his well-equipped horsemen, Frémont found Sutter hospitable. The two men feasted together and discussed the political climate while sharing ample drafts of wine. Four days later, Frémont took eight of his men on Sutter’s schooner Sacramento to explore Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco) and to visit the U.S. vice consul. From there he decided to take his party 100 miles south to Monterey, where he would present the Mexican officials with a passport from Sutter authorizing his passage.

Much has been made of Frémont’s movements from this point onward, and historians have long debated his motives, instructions, and activities. After a few days at the vice consul’s home, he set off on January 24, 1846, for Monterey—California’s serene, strategic center, over which Castro presided from his customhouse headquarters under the Mexican flag. Frémont’s first visit was to the U.S. consul, Thomas Larkin, a shrewd Massachusetts entrepreneur who had been one of the first Americans to settle there. Highly regarded by his Mexican neighbors but keenly aware of the escalating tensions, Larkin advanced Frémont $1,800 in government funds to buy supplies. Frémont’s arrival in Monterey was immediately conspicuous, prompting a pointed Mexican inquiry about the party’s nature and mission. Larkin replied that Frémont was leading a scientific expedition to Oregon and had stopped in Monterey only for provisions.

Frémont also paid an official visit to Castro and did his best to allay the ruler’s concerns, insisting that his survey was manned entirely by American civilians. Though unconvinced, the Mexican officials granted him permission to obtain supplies and travel freely. After traveling 60 miles north to an abandoned ranch near the Santa Clara Valley, Frémont flagrantly violated his pledge to the Mexicans by leading his party on February 22, 1846, in a steady march to the southwest. Five days later they pitched camp 20 miles from Monterey, where he received a letter from Castro demanding that he leave California immediately.

Frémont coldly responded that he would not obey a command insulting to both him and his country, and he proceeded to move eight miles north to the crest of Gavilán (later Fremont) Peak—a strongly defensible position with plenty of water and grass for the livestock as well as a commanding view. The men built a log fort and cheered wildly as they raised the American flag on a sapling—a gesture that destroyed the last vestiges of Mexican goodwill.

On March 8 Castro began recruiting volunteers to dislodge these intruders. Unknown to both sides, that same day Taylor’s troops crossed into disputed territory, marking the practical beginning of the Mexican War. For three days Frémont and his men watched as Castro’s forces swelled to 300, backed up by three large cannon. Larkin frantically mediated, urging Frémont to withdraw; but with panache and bravado, Frémont scrawled a note to Larkin, “if we are hemmed in and assaulted, we will die every man of us, under the Flag of our country.”

The California settlers were deeply alarmed and agitated. Desperate to prevent a clash that might spark war before the U.S. government was fully prepared, Larkin, who assumed that Frémont was acting under orders from Washington, warned him to be watchful for spies and traitors. Just as Castro seemed about to attack, Frémont’s sapling flagpole fell over, which he took as an omen: “Thinking I had remained as long as the occasion required, I took advantage of the accident to say to the men that this was an indication for us to move camp. . . . I kept always in mind the object of the Government to obtain possession of California and would not let a proceeding which was mostly personal put obstacles in the way.”

However awkward his situation, Frémont made a leisurely and deliberate withdrawal, not a hasty retreat, slowly and defiantly dropping down into the San Joaquin Valley toward Sutter’s Fort, where jubilant settlers greeted them. While Castro boasted of a victory, Frémont’s men held their heads high—and justifiably so, in view of their having stood off a force five times their number. “Of course I did not dare to compromise the United States,” wrote Frémont to Jessie. “Although it was in my power to increase my party by many Americans, I refrained from committing a solitary act of hostility or impropriety.” Indeed, a prominent American settler offered to raise a company of frontiersmen. And the captain of an American merchant ship anchored in Monterey Bay declared himself ready to establish a stronghold on the coast. Frémont declined both initiatives, although he “could have mustered as many men as the natives,” reported Larkin to Buchanan. Even Castro seems to have been impressed by his opponent’s determination in the face of seemingly hopeless odds, conceding to his troops that Frémont “has conducted himself as a worthy gentleman and an honorable officer.” Both men had managed to maintain dignity without shedding blood.

Meanwhile, Larkin had circulated a general letter to “the commander of any American Ship of War” asking that a sloop be sent immediately to Monterey. Frémont headed north, reaching the foothills of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon, where two exhausted advance couriers from Lieutenant Gillespie reached him on the evening of May 8. Gillespie had just arrived in California, they told him, bearing a confidential message from Washington. The next morning Frémont and 10 men rode hard over 60 miles of rugged terrain to reach Gillespie’s campground at the southern end of Klamath Lake. It had been 11 months, wrote Frémont, “since any tidings had reached me.”

What Gillespie told him that night, the content of the letters he was given, the oral instructions from Bancroft, have all been left to speculation. Frémont’s account—written 30 years later—was deemed accurate and credible by his supporters, obfuscating and self-justifying by his many enemies. Perhaps the most revealing of such official documents that survive is Buchanan’s handwritten letter of October 17, 1845, to Thomas Larkin that articulates President Polk’s intention. “In the contest between Mexico and California (which was at times acute) we can take no part, unless the former should commence hostilities against the United States; but should California assert and maintain her independence, we shall render her all the kind offices in our power, as a sister republic. This government has no ambitious aspirations to gratify and no desire to extend our Federal system over more territory than we already possess, unless by the free and spontaneous wish of the independent people of adjoining territories.”

Singularly informed as Frémont was from his preparatory 1845 meetings with Benton, Polk, Buchanan, and Bancroft, he understood that he was to set off a “spontaneous” revolt apparently unsponsored by the U.S. government. Gillespie, who had traveled through Veracruz and Mexico City, knew that war had broken out and that the president’s negotiations to purchase California had failed, and he presumably informed Frémont of the situation.

“Absolved . . . from my duty as an explorer,” wrote Frémont later, “I was left to my duty as an officer of the American Army with the further authoritative knowledge that the Government intended to take California . . . it had been made known to me now on the authority of the Secretary of the Navy that to obtain possession of California was the chief object of the President.”

Layered as they were through a shifting chain of authority, Frémont’s orders would be subject to partisan interpretation. He was the only U.S. Army officer present in California and would remain so for the next nine months. Yet Frémont had little doubt of what to do next, swiftly moving his party to an isolated series of bluffs along the Bear and Feather rivers, where they were reinforced by “rough, leather-jacketed frontiersmen” eager to strike Castro’s position. As they pressed south, more dissident American settlers joined them. The number of Americans in California had swelled to more than 800 in the previous two years, nearly all of them ranchers, trappers, hunters, merchants, and farmers, interspersed with rugged backwoodsmen, sailors, and voyageurs.

On June 10, with Frémont’s behind-the-scenes encouragement, the settlers brought in 200 horses being driven to Castro from the Santa Clara Valley. Four days later, a group of 30 rebels seized Sonoma, the largest settlement in northern California, and took four prominent citizens prisoner.

On the next day, amid a brandy-fueled celebration, they hoisted a primitive linen flag on which was painted a grizzly bear and declared themselves the proud commanders of the Bear Flag Republic, emboldening several hundred more immigrants to join the rebellion.

Frémont soon learned that Castro and hundreds of mounted Mexicans were advancing up the Sacramento to burn American settlements. He still kept his men on the sidelines, however, neither openly supporting nor dissuading the rebels, following Buchanan’s orders to inspire a “spontaneous” revolt only tacitly and discreetly.

By late June, the Anglo rebels effectively controlled northern California from Sutter’s Fort to Sonoma. Once the USS Portsmouth entered San Francisco Bay, Frémont openly joined the rebellion, racing with 100 men to Sonoma on word that Castro was on his way to retake it. Finding no Mexican soldiers, they marched to San Francisco and back, meeting no Mexican troops at any point. At the Fourth of July celebration in Sonoma, complete with a public reading of the Declaration of Independence, the rebels put themselves under Frémont’s command. Three days later, under orders from Washington to occupy San Francisco and all other ports, the Pacific squadron—three frigates, two transports, and three sloops—was poised off the coast. On July 7, 250 sailors swept into Monterey and raised the American flag above the central plaza. Frémont learned that the U.S. Navy now occupied San Francisco.

Commodore Robert Stockton arrived aboard the USS Congress, formed the Battalion of Mounted Volunteer Riflemen, and placed Frémont in command. Frémont then recruited 428 men around Sonoma and Sutter’s Fort, as well as 50 Walla Walla Indians from Oregon, paying them the liberal salary of 25 dollars per month. He planned to move south to Los Angeles, seizing the towns along the way; but Stockton ordered him to take 150 men aboard the Cyane to San Diego. Having raised the American flag there on July 29, they marched north to Los Angeles, taking control from both Castro and Pico on August 13.

Stockton sailed north, convinced that the conquest was complete, while Frémont took his troops overland to Monterey, leaving Gillespie in charge of Los Angeles. After Gillespie found himself in trouble from Mexican insurgents, Stockton ordered the battalion back. On January 13, 1847, after a few brief skirmishes, Frémont received the surrender of the remaining Mexican forces at Cahuenga Pass outside Los Angeles, granting them generous capitulation terms, which he himself drafted. It guaranteed their lives and property and permitted them either to return to Mexico or to remain in California with the same rights and privileges as American citizens. Once they had turned over their arms, they were free to go home and would not be required to take an oath of allegiance to the United States until a final peace treaty.

Amid cheers and fireworks, Frémont proudly led his men back into Los Angeles. On January 16, 1847, Stockton named him civilian governor of California. “The territory of California is again tranquil,” Stockton wrote to the Navy secretary, “and the civil government formed by me, is again in operation in the places where it was interrupted by the insurgents. Colonel Frémont has five hundred men in his battalion, which will be quite sufficient to preserve the peace of the territory.”

Such was the state of affairs as Jessie knew it when Stockton’s report arrived in Washington. Her husband was a hero. It thus came as a devastating shock to learn that Buchanan was publicly accusing Frémont of acting impulsively and outside his authority, and that several newspapers were reporting his arrest for insubordination. She clung to the hope that Buchanan was running interference for the State Department. New Englanders and Midwesterners, along with Europeans and Mexicans, roundly decried the Polk administration’s imperialism, and although the president at the outset had strongly supported Frémont’s mission, he now backpedaled. The United States was not seeking empire, Polk would maintain, but merely trying to establish peace and order after a conflict instigated by—conveniently for the president—a rogue explorer.

Frémont’s problems began when he accepted his appointment from Stockton and refused to acknowledge Army Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny, who had been enraged when overshadowed by Frémont’s effecting the dramatic surrender at Cahuenga Pass. When Kearny appeared in San Diego in December 1846, he was in no mood to endure the antics of an irregular junior Army officer. The 47-year-old Kearny—a spit-and-polish martinet known as “the father of the U.S. Cavalry”—was set on putting Frémont brutally in his place. The following June, Frémont was arrested and marched from California to Washington under the custody and surveillance of Kearny, who forced him to trail behind Kearny’s men.

On January 31, 1848, after deliberating for three days, a jury composed of 13 military officers found Frémont, one of the U.S. Army’s most celebrated and popular figures, guilty on three charges and sentenced him to dismissal. But seven of the jurors cited his distinguished service and recommended that he be granted clemency by the president. Polk immediately did so, ordering him to “resume his sword.” Frémont instead submitted his resignation.

Frémont had certainly known the risks when he had agreed to undertake the covert assignment, and he would have been willing to take the fall had he failed. On the contrary, California had capitulated with astoundingly little bloodshed. But his reward for swiftly obtaining a province as large and rich as a European great power had been humiliation. Though public sentiment was firmly on his side, Frémont was fated to be among the earliest American undercover operatives to be sent into the swamp by a calculating president.

His father-in-law would draw the final implication: Frémont’s worst crime, according to Benton, had been to distinguish himself without graduating from West Point.