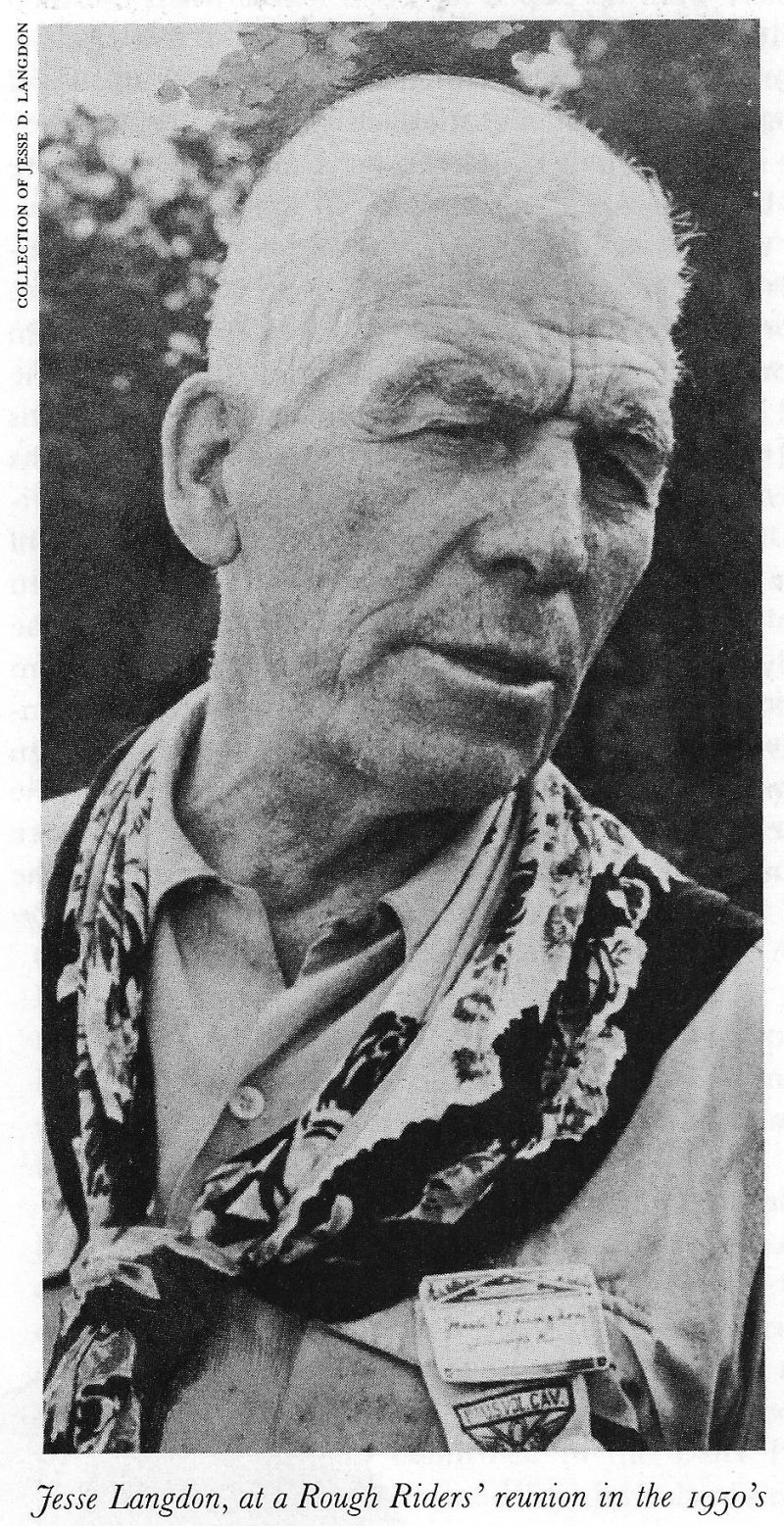

He had vivid memories of fighting in Cuba with Theodore Roosevelt. “We’d have gone to hell with him.”

-

August 1969

Volume20Issue5

“In strict confidence, I should welcome any war, ” wrote Theodore Roosevelt in 1897. “The country needs one.” And soon enough the bellicose assistant secretary of the Navy had his wish: after a long period of neutrality, President William McKinley (to whom T. R. ascribed “no more backbone than a chocolate éclair”) decided to intervene in behalf of the Cuban revolutionaries fighting for independence from Spam. On April 25, 1898, the United States declared war on Spam. Roosevelt—father of six—itched to get into the action. He resigned from the Navy Department and announced he was going to join the cavalry regiment being organized by Colonel Leonard Wood. The press promptly termed the outfit the Rough Riders.

“In strict confidence, I should welcome any war, ” wrote Theodore Roosevelt in 1897. “The country needs one.” And soon enough the bellicose assistant secretary of the Navy had his wish: after a long period of neutrality, President William McKinley (to whom T. R. ascribed “no more backbone than a chocolate éclair”) decided to intervene in behalf of the Cuban revolutionaries fighting for independence from Spam. On April 25, 1898, the United States declared war on Spam. Roosevelt—father of six—itched to get into the action. He resigned from the Navy Department and announced he was going to join the cavalry regiment being organized by Colonel Leonard Wood. The press promptly termed the outfit the Rough Riders.Langdon grew up in Dakota Territory and, as a boy of six, met Roosevelt when T. R. was a rancher there m the eighties. In 1898, shortly before Langdon’s seventeenth birthday, he heard about Roosevelt’s proposed regiment. He hopped a train and rode hobo-style to Washington. He vividly recalls hurrying to the second-floor recruiting office on E Street near the Capitol. There he bumped into Roosevelt, who was coming down the outside stairway. The surprised youth blurted out, “You’re Teddy Roosevelt!” As Langdon recalls it:

Colonel Roosevelt stopped and said, “Yes, sir, what can I do for you?”

“Why,” I said, “I’m Jesse Langdon from North Dakota, and I’ve beaten my way here on the train to join your Rough Riders.”

“Well, can you ride a horse?” asked Roosevelt. [Langdon, who could run a hundred yards in ten seconds, was well on his way to a full growth of six feet and 225 pounds.]

“I can ride anything that’s got hair on it,” I said.

He laughed. He had a funny way of laughing. He just went “Hah!” with his teeth set, and those in front showing. Then he told me to go upstairs and tell them he had sent me.

I will never forget the way he talked when he later got some of us over at his office. He was assistant secretary of the Navy, you know. It was some pep talk. He said, “Now, boys, any of you who don’t want to put up with the hardships you’re going to face can drop out right now. We’re going to get there first, and that means you’ll be putting your life on the table.”

When we were getting ready to leave for the training camp in Texas, I said, “Mr. Roosevelt, I haven’t been sworn in yet.”

He said, “Hah! Well, I’ll swear you in personally when I get to San Antonio.”

Several days later, when they arrived at San Antonio, Langdon reminded him of his promise.

When I went to his tent, Roosevelt was seated at his desk, and he had his Bible—he always had a Bible on the table—and I says, “You promised to swear me in.”

“So I did,” he says, “so I did.” He says to me, “Let’s get back here where everybody won’t see us.”

He got up with the Bible in his hand and led me around behind the tent. Then he had me put my right hand on the Bible and my left hand up, or vice versa, I forget which, and, “Hah,” he said, and swore me in, see. He had a smile on his face all the time. A week later, when they swore the whole regiment in, I realized why he was laughing. He was just humoring me, giving in to my impatience and youthfulness.

Most of the troopers were westerners—cowboys, miners, trappers, trail riders, lawmen; the others were from the East Coast-college athletes, socialites, and sons of wealthy families.

A horseman of the first order, Langdon developed into one of the best riders m the regiment. He volunteered, along with Billy McGinty, a little bowlegged cowboy from Oklahoma Territory, and other experienced broncobusters, to break horses. Spectators came by the thousands to watch and to marvel at their skill.

Langdon remembered San Antonio mainly for its dust.

It made us look black. When we were practicing there, you couldn’t breathe. We had a mess breaking those horses in that dust, a regular melee. It was days before we got straightened out so we could really drill. Yes, and some of the boys got hurt, bucking, throwing, and so forth.

We slept in the old amphitheatre where they made the exhibits for the county fair. That amphitheatre was infested with scorpions and these big spiders—tarantulas, you know—by golly, that’s one thing that really did get my goat.

He recalled the tiresome, hot tram ride to Tampa, where the regiment would embark for Cuba.

We loaded up at night. One end of the car on which I was riding was reserved for the boys who were not feeling well. We had a fellow with us called San Antone, and he had killed a couple of men, and he was a tough hombre. I was on guard when he walked up and grabbed a sick man by the foot and pulled him off the seat. I went up and I said, “Look, this is for the boys who are ailing and you’ll have to get out of this seat.” So he pulls a knife on me, and I threw a carbine down on him and took him out of there.

Well, the next day the train was stopped above a big slough, and we had to go down the embankment to get water to wash. I brought my basin up to wash on the steps of the car, and by golly, this guy come up and kicked me in the face and knocked me clear down the embankment. Well, I just come up that embankment punching mad, you know—he tried to kick me again, but I grabbed his foot and pulled it aside, and I grabbed him by the top of his shirt and put his head through the car window and cut a gash all under his ear. That took care of him.

At Tampa, Roosevelt requisitioned a coal train—he had to force the engineer to take us because the train was on some other mission—and we loaded onto that and went to the port where the boats were located. There was a boat there that had been assigned to another outfit, but Roosevelt got us on before they got there. He made sure that we were going to Cuba, and he got us there. That’s the reason we landed—because Teddy just suddenly took over and saw that we got there.

The regiment sailed on June 14. Life on board ship was “pretty tough.”

They furnished us with a lot of embalmed beef. It was supposed to keep in any weather. Well, we had it hung all around the deck and it commenced to explode. We had to throw it all overboard, and then we lived on canned meat and tomatoes. After we got in Cuba, of course, we all starved. Roosevelt didn’t get any food for us. He’s a little bit mistaken about the food he mentioned in his history. At least I didn’t see any of it. Food didn’t get to many of the privates. I’m giving you the facts. I’ll tell you, the officers had the best of it.

By the time the Rough Riders embarked at Tampa, an American fleet was waiting off Santiago de Cuba, where a Spanish naval force lay under protection of land batteries. The mission of the American land forces, of which the Rough Riders formed a part, was to capture the port of Santiago while the fleet kept the enemy ships bottled up.

Of the invading army of 17,000, the Rough Riders were among the first to land. Two days later, on June 24, the ist Volunteer Cavalry—minus their horses, j which had been left in Florida—led a victorious attack on a Spanish position at Las Gudsimas, east of Santiago.

For the next six days the Americans lay in camp, organizing their drive toward Santiago.

The Spaniards had fallen back to a ridge on the outskirts of Santiago, along San Juan and Kettle hillsᑜ the latter highland named for the huge kettles on its crest remaining from a former sugar distillery. These kettles would be the Riders’ goal.

I’ll have to start before Kettle Hill. We woke up [after a night march] at El Poso on the morning of the first. El Poso was about a mile and a half before you get to San Juan River, which you had to cross to go to San Juan Hill. There was a road there, and there was [an American observation] balloon there that was attracting the fire of the Spaniards and made it pretty tough. I mention that as a sort of side issue so you can get a picture of the whole thing.

Anyhow, that morning Grimes’s battery opened up from El Poso on the Spanish batteries in Santiago. Well, of course they had the range of El Poso ans some of our men got wounded there. We began to duck.

That was one time I saw Teddy lose his temper. He came running up and said, “What in hell’s the matter with you fellows? Damn it, what are you, a bunch of sheep?” He says, “Get up there and line up.” Yes, sir, and then, “Clerk, call the roll,” We had to line up on top of that hill under fire, and the clerk called the roll. “Dress on sergeant Higgins,” Roosevelt told us-but Higgins was stooping over just like the rest of us! “Now,” Roosevelt says, “march down here under fire.” That was him. And by golly, there lay a soldier right in front of him with a leg shot clear off. Laying right in front of him.

That was just prior to the march down to the river to go across to San Juan Hill. We marched down the road and underneath the balloon and into the San Juan River, so Roosevelt had to deploy us out of the line of fire when we reached the far bank. We just lay there spread out about 150 yards along the bank until the officers went across the river and looked the ground over. I had been over there the night when we took Captian John H. Parker and his battery of Gatling guns over there and set them up. They were already there, on the far side of the river.

As we came out of the river, why, Henry Haywood, who was a New York policemen, was shot just as we came out of the ford; it sounded like somebody put their first into a pillow. And he says, “I'm hit!” He was shot in the abdomen, right there by the river. He died.

Then we started up over the canebrakes. Woodbury Kane was our captain, and he insisted on carrying a sabre with him. It got between his legs, and he had to carry it over his shoulder with a six-shooter in the other hand. He says, “Oh, Jesus, I’m scared.” He says, “But, by God, I’ll stay with it.” Imagine it! He was president of the American Tobacco Company at that time and a multimillionaire. But, boy, he meant it. He didn’t follow us. He was like Teddy. It was “Come on, boys” with him. He had what it takes.

We went up across the canebrakes. Our path led right into another loop of the river, so we were told to go straight ahead. When we got across, there was a kind of an open place, and a sharpshooter had our range, and it was pretty hot in there—he didn’t hit any of us, but bullets were coming all around us into the mud, so we had to go back to the canebrakes because there was no way to go ahead.

We went back across the river, and I stuck my gun into the clay embankment, and I climbed up on my gun and crawled out.

Well, I was laying there—I took the ramrod out of my gun, and I was taking the muck out of the barrel, and General Chaffee came along on a horse. I didn’t know who he was, but I found out afterward. He says, “What are you doing—hiding?”

I says, “No, goddamn you, I don’t have to hide from anybody.”

General Adna R. Chaffee commanded the brigade containing the corps with which the Rough Riders served.

After leaving General Chaffee, I went along and I could hear yelling up ahead of me, so I ran to beat the band. It was the members of the Ninth Regular Cavalry. I knew some of them were mixed up with it.

The 9th, a Negro regiment, was part of the ist Brigade. Along with the Rough Riders they had been waiting for orders at the foot of Kettle Hill. When Roosevelt, impatient with the delay, led his troops through the yth before making the charge, the officers of the 9th ordered their men to go up the hill in support of the Rough Riders, so that there has always been some question as to which regiment reached the top first.

I got up to the Ninth and I caught up with a bunch of white people, and we went up the hill. There was a pond at the bottom of the hill—sort of between San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill. The pond was about an acre or so, I guess, and we went up on the right-hand side of it because we were following Teddy.

Incidentally, we had been ordered to retreat before that, but it wasn’t authenticated. Teddy didn’t pay any attention to it anyhow. He went ahead, and we started to go up the hill. We got everybody together- cavalry and some infantry—I don’t know who they were. We were all mixed up there along the bottom.

We went up the hill, and we went up to the right—open grass all the way, it was wide open. We didn’t run all the way. We’d run a ways and then stop. You had to because you couldn’t run uphill forever. We didn’t run in a regular line. One part of the line would be lying down and another part would be going up. It was just like a mob going up there. Some men got over on the other side of the pond and they actually went up San Juan Hill, but we were on Kettle Hill.

“Roosvelt was right there in the middle of it. He was fearless. If he had fear, nobody knew it.

In Langdon’s memory of the charge, one incident stands out that is not mentioned elsewhere: that Roosevelt’s glasses were shot off while he was riding his horse up the hill.

I can see him there yet, fumbling in his pocket for another pair. He found them and put them on and kept going. He was right there in the middle of it. He was fearless. If he had fear, nobody knew it.

Roosevelt makes no mention of the incident in any of his writings. Had the glasses been shot off he probably would have recorded it, as he did other brushes he had with enemy fire. Because of nearsightedness, he usually kept several pairs of glasses of the pince-nez type at hand, and in the excitement of battle he doubtless lost the pair he was wearing when he started the charge.

We were exposed to the Spanish fire, but there was very little because just before we started, why, the Gatling guns opened up at the bottom of the hill, and everybody yelled, “The Gatlings! The Gatlings!” and away we went. The Gatlings just enfiladed the top of those trenches. We’d never have been able to take Kettle Hill if it hadn’t been for Parker’s Gatling guns.

I don’t know of one of the Rough Riders who was killed during the charge—by a Spanish bullet. If I may say so, they were all shot from behind. They were killed. That’s the truth. I got behind one of those huge sugar kettles on top the hill and found the gunfire was coming from behind.

Most of the Rough Riders were dressed in somewhat nondescript khakis instead of the blue uniform worn by other regiments. During the battle, some of the regulars apparently mistook Roosevelt’s men for the enemy. Uniforms are still a sore subject with Langdon.

We actually never had any uniforms—just these winter fatigue outfits. The only uniforms the Rough Riders got—except the officers—were issued them on Long Island after they got back. I went home in my old brown jeans, my old stinking brown jeans. They were like overalls, and the dye in them had a foul smell. They also gave us those damned blue woolen shirts. They almost killed us with heat. I took my shirt off and tied it around my neck and let it hang down my back.

In recalling the stiff-brimmed hats they wore, the veteran remembered his narrowest escape. A bullet went through the back brim of his hat as he bent to work the lock of his carbine.

If I had been standing straight, it would have hit me right in the forehead.

Incidentally [returning to Kettle Hill], there was a little ravine off to my left, and there was a Negro there, and he called to me. I went over, and he says, “This is my son,” pointing to a young man on the ground who was bleeding badly. He says, “Can you stop this blood?”

I took my first aid out and I made a knot of it, and I got his first aid and made a knot. He had been shot through an artery. I made a plug out of the first aid. I said, “I’m afraid it’s too late to do him any good,” because I could see his eyes were tipping, and he went.

So I took a minute or two there, and then I went back out, and by the time I caught up with them Teddy was sending Billy McGinty back with his horse. He says to McGinty, “I want this horse after the war.” He had come to some barbed-wire entanglements [just below the top of the hill], so he sent McGinty back with his horse.

Roosevelt went on and overran the trenches, and he was maybe seventy-five yards ahead of us—he was always ahead of us. There was two or three fellows that started over after him. I’ve forgotten who they were, but I wasn’t one of them, and he came back—he found he was alone. He looked around and came back. That was the charge as far as I’m concerned.

By late in the day, the Spaniards had been driven from San Juan and Kettle hills back toward Santiago. The Americans dug trenches and moved up reinforcements. During the night of July I, Langdon felt some pity for the enemy.

I was ashamed of myself to be killing them, because most of them were kids. It was a damned shame. When I went up to the trenches that night and walked along them and saw these boys in there dead—little boys, with men’s shoes on, manila-rope-soled canvas shoes. Some of them had three or four bullet holes in the head. They looked like children. It made me feel ashamed. A lot of the boys said the same thing.

On July 3, the Spanish fleet sailed from Santiago Bay and was sunk by the American ships. Negotiations began, and finally, on July 11, Santiago was surrendered.

In the interim, the Americans lay in trenches, and sickness spread rapidly. Langdon was a victim.

I was lying there in the trenches before I went out under yellow fever, and Roosevelt came right up and stood over me and talked to me. He said, “Hello, Langdon. How’re you getting along?” I can see him bubbling. There was nobody quite like him, I’m telling you. Men were drawn to him because they knew he was the right man. We’d have gone to hell with him.

Langdon fared well. Recovered from yellow fever, he was one of thirteen Rough Riders who toured the country in 1899 as a part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. In 1900 he went to England to buy horses, and while there (his weight much reduced by sickness) fought the middleweight champion of England to a drain. Over the years he practiced as a veterinarian, and while living on a ranch in Washington state he served as an unlicensed doctor, because there was no physician within a hundred miles. He has been a builder, surveyor, machinist, and plumber; he holds 189 patents in fields as diverse as aviation and beauty aids.

In Lafayetteville he fishes, works on an economics book he is planning to publish, and writes a fair number of letters. Often he signs himself “Jesse D. Langdon, the last man—K Troop, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders.”