TR’s zeal for athletics helped lead to the emergence of modern sports in America, including interscholastic competition, the NCAA, the World Series, and the first Olympics in the U.S.

-

Winter 2020

Volume64Issue1

Many Americans are obsessed with sports, either watching or participating. But few realize that in many ways our nation's fascination with athletics began when a energetic young man, Theodore Roosevelt, occupied the White House. Portions of this essay appeared in Ryan Swanson's fascinating recent book, The Strenuous Life: Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete.

--The Editors

“This is the White House. The president would like to have you to play tennis this afternoon at 4, if you are free.”

Years later, Lawrence Murray still remembered the thrill of receiving this call. Of course, he was free; Murray had recently been appointed assistant secretary of the Department of Commerce and Labor. He was new in town, or at least newly back in town. He also happened to be a decent tennis player. So, suspecting nothing other than some important face time with the president of the United States, Murray showed up at the appointed time and place. But first, he shopped for the occasion. Thus Murray, “a round young man with a pleasant laugh and a calm manner,” looked downright resplendent when he arrived, sporting a brand new, white, “spick and span” tennis getup.

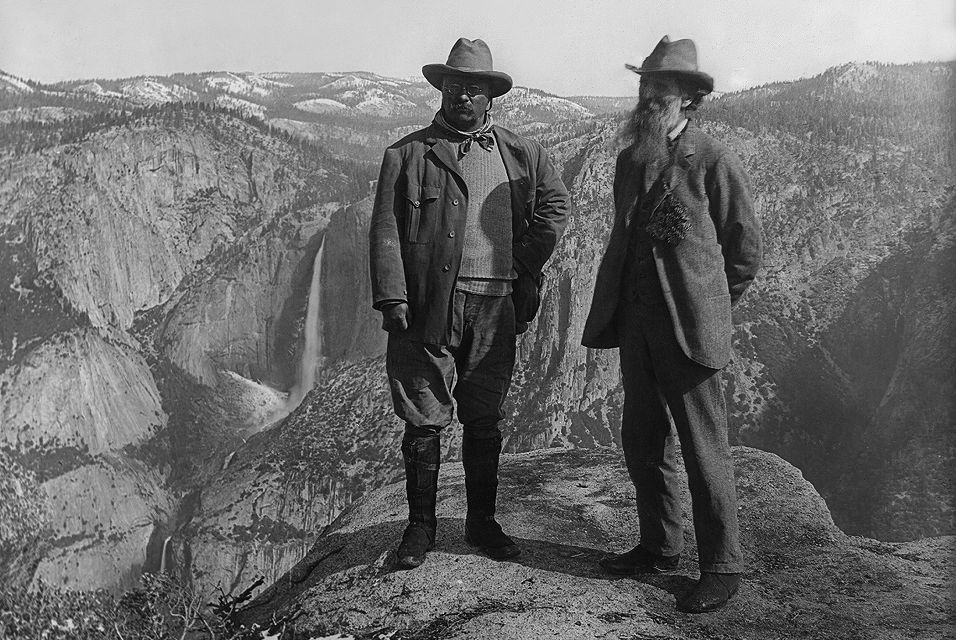

President Theodore Roosevelt, in contrast, wore a brown “army shirt,” thick, well-worn khaki knickers, and black boots. This was the official uniform of “the Strenuous Life,” the athletic crusade for which Roosevelt had become so well known. Roosevelt greeted Murray warmly. Rounding out the playing group were Director of Forestry Gifford Pinchot and Secretary of the Interior James Garfield.

Right away, things went poorly for Murray. Feeling a bit overwhelmed, he prayed silently that he would not be paired with the commander in chief. Too much pressure there. He did not want to bear responsibility for a presidential loss — even if it was only on the tennis court. But when the four men tossed their rackets in the air to select teams, Murray’s and Roosevelt’s landed facing the same direction. Partners.

“I did not know the president at all then, and to find myself his partner in tennis, when I had not had a racket in my hand for months, while he was in good practice, and so were the others,” Murray remembered, “was a little upsetting to say the least.”

Murray had his hands full on the court. Garfield and Pinchot both played splendidly. Roosevelt, on the other hand, played with…well…great enthusiasm. “Somehow his racquet seemed too short, and the little, tantalizing ball too small,” reported the Washington Post of the president’s game on a rare occasion the press was allowed to observe a White House match.

Roosevelt had the bad habit of drifting into no-man’s-land as his partner served. “The President stands too close to the net for so stationary a player as he is. Ball after ball goes by him.” Thus the partner — Murray in this case — raced around trying to pick up the slack. “The other fellow in the back court, chasing from side to side, does all the work,” the Post explained, summing up the Team Roosevelt tennis experience.

The whole group was sweating profusely. President Roosevelt had outfitted his White House tennis court (installed in 1903, replacing several of William McKinley’s greenhouses) with a twenty-foot-high canvas fence. The canvas worked perfectly in terms of privacy, but it also created an airless womb of athletic activity. Only a few games in, Murray had serious doubts about his ability to survive due to the stifling environment.

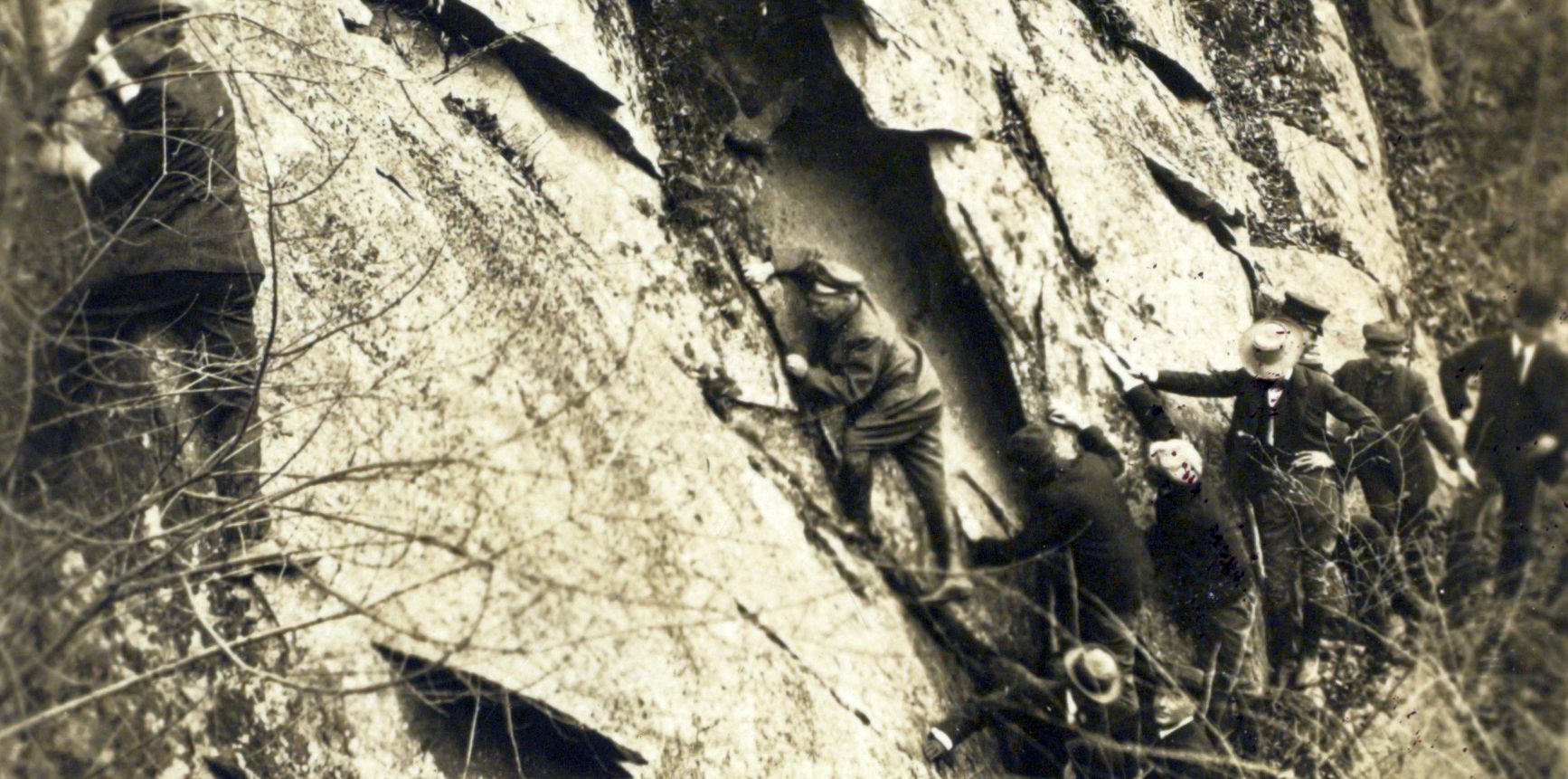

Fortunately for Murray, a summer thunderstorm intervened before too long. The group ducked into the president’s office as the skies opened up. The White House tennis court was attached directly to the Executive Mansion. The play-to-politics proximity had actually been one of the first things that Murray noticed upon entering the White House grounds. The president could, basically, step “from his office door on to the court.” Murray rejoiced at a reprieve by rain. He had been saved. However, visions of handshakes and drinks were summarily dashed. With rain pummeling the District, the president pivoted quickly. He had a new, adventurous plan. “To my utter amazement Roosevelt said: ‘Just the day and time for a long walk and run.

For Murray, they might as well have been stomping into the Amazon rainforest. He was aghast at the thought of leaving the landscaped White House grounds. “Within a few roads of the White House was then a marsh, or rather an almost impenetrable jungle of weeds, marsh grasses, cane brakes covering a soft black muck,” Murray recalled. Into the slop they went. Roosevelt, not completely inconsiderate of his newcomer’s plight, offered a quick bit of advice: “Tie your shoes on extra tight, or the muck will pull them off.”

The foursome sloshed its way through thick underbrush and across a small creek. Roosevelt could not get enough, comparing the relatively tame mud and mild conditions of Washington DC to the brutal conditions he had confronted on a recent hunting trip to Louisiana. While the president beamed and bounded, Murray pouted. “I could not get much amusement out of such a mess.” Murray also fell back quickly, “losing time here and there as the black sticky muck pulled off first one shoe and then the other.”

The group crossed into the Old Dominion and plowed ahead. Just when poor Lawrence thought he couldn’t take any more, Roosevelt announced: “We will now run every step of the way back!” announced the middle-aged, stocky leader of the group.

At this point, Murray needed no further convincing: Roosevelt was crazy. “If at first I had my doubts of his sanity, I was now firmly, finally, and totally convinced. I was already tired out getting through the jungle, we were all completely covered in mud, the rain was still falling in torrents and four miles yet to go and on the run.”

Roosevelt, Pinchot, and Garfield trotted away at a steady pace, ambling back toward the White House, keeping up a lively conversation along the way. Murray was left for dead. “After about a mile I was in agony.…I was entirely out of condition, having had no exercise like that for years. After another mile between walking and running, I stopped, but the others never looked back, so I saw them disappear while I was utterly unable, if my life depended on it, to barely move.”

Lawrence Murray did not perish in the wilds of northern Virginia. Upon reaching the White House and realizing just then (or so they said) that Murray had failed to keep up, Pinchot and Garfield reversed course to recover their fallen comrade. They found him a mile back. “One took one arm, the other another, and hustled me along to the hotel.”

Murray later found out that Garfield and Pinchot indeed knew what was coming. The two men had been on Roosevelt’s impromptu jaunts before — across all manner of terrain, in violent weather, and always with their boss, the president, annoyingly declaring how wonderful it was to be out in nature. “Bully!” this and “Deeelightful!” that.

More than being mentally prepared, Garfield and Pinchot actually trained to keep up with the president. They advised Murray to “get into good physical condition as quickly as possible.” They even recommended an athletic trainer for the task, one whom Murray had hired within twenty-four hours of his muddy embarrassment.

After all, Murray — like all Americans — had to keep up with his president.

How did we get this way? In terms of sports and athletics, that is. This first question then, as initial questions often do, splintered in all sorts of directions. Why does the United States, unlike most civilized countries, comingle education and athletics? What’s the deal with the Army–Navy football game? Has the United States always dominated the Olympic Games medal count? Is baseball (or football or basketball — it’s obviously not soccer or hockey) really America’s “national pastime?”

Mostly we don’t ask. Most Americans just do sports — from Little League to Super Bowl parties — simply because it’s the red-blooded American way.

The search for answers to the above questions leads, eventually, to the first decade of the twentieth century. And the search zeros in one US presidential administration. During the time Theodore Roosevelt occupied the White House, modern sports emerged in America. In essence, the period was a supercollider. Sports banged around in a pressurized drum at speeds and volumes previously deemed impossible. Out of the pressurized period came a labyrinth of infrastructure, tradition, and sporting norms. An American athletic paradigm emerged. It is the same athletic paradigm, to a significant extent, that still reigns today.

Thus muddy and shoeless Lawrence Murray was a casualty of a revolution he did not even know was happening. During the administration of Theodore Roosevelt, or the Strenuous Era as we might as well call it, the landscape of American sports changed dramatically — at the White House and beyond. From 1901 to 1909, the sports precedents piled one upon another. Here are just a few:

* In baseball, the American and National League worked out a monopolistic merger. Begrudgingly (and somewhat surprisingly), the rival circuits agreed to stop poaching players from each other. Out of this agreement came the first World Series in 1903.

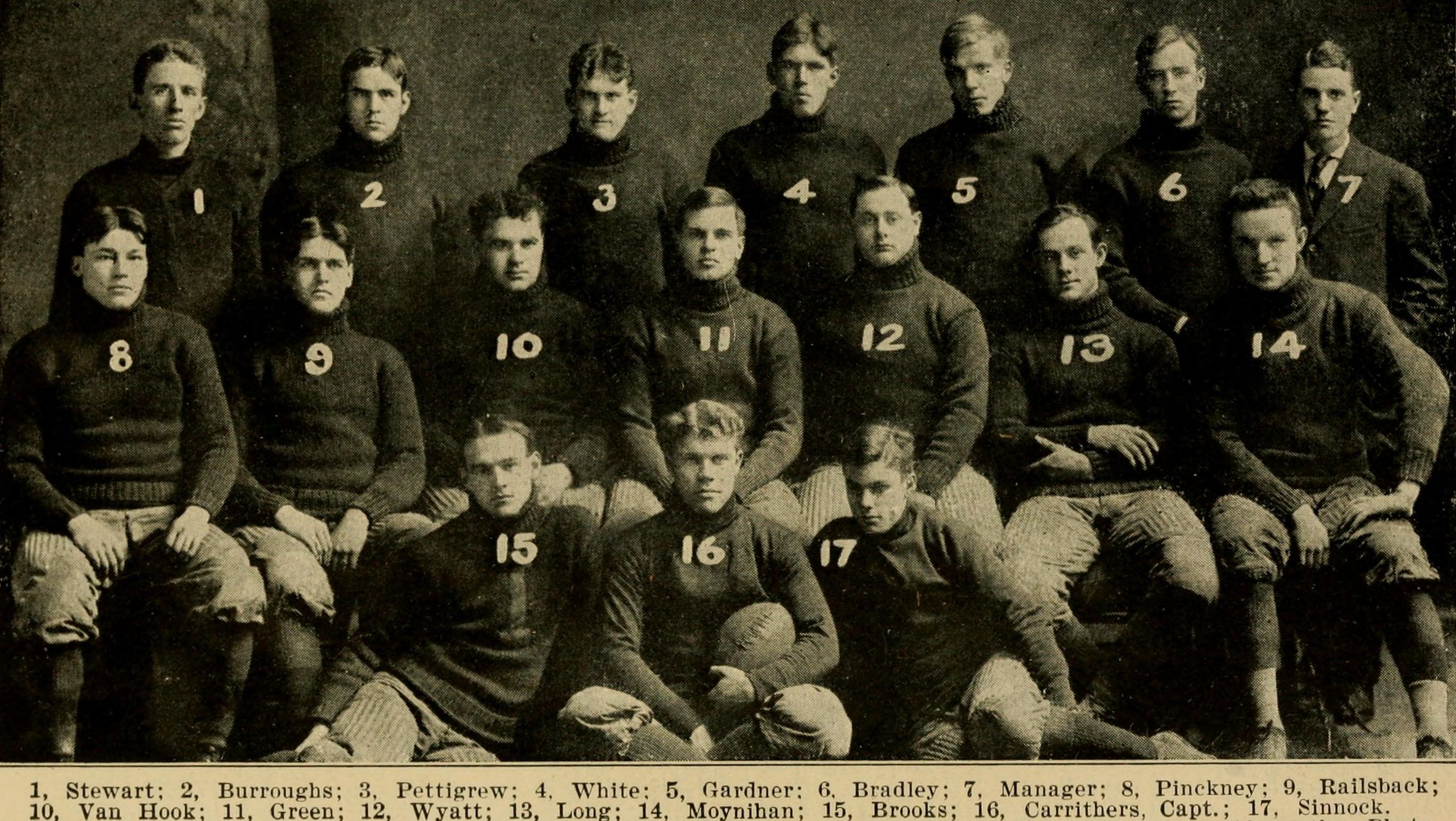

* On university campuses, football’s popularity boomed. The game, however, was exceedingly violent. So much so, that the number of football casualties sparked outrage. With abolition efforts swirling, including one at a school close to Roosevelt’s own heart, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) emerged in 1906 as a means of regulating intercollegiate sports.

* In 1904, as Roosevelt faced a presidential election, the United States hosted its first Olympic Games. To make matters more interesting (and shed some insight on baseball’s Cardinals-Cubs rivalry), St. Louis stole the games from Chicago at the last minute. St. Louis then turned the games into a months-long celebration of American conquest.

* Also during this Strenuous Era, Jack Johnson worked his way toward becoming America’s first African American heavyweight boxing champion. Johnson defeated all comers in the ring but could not get a title fight for years. Finally, during Roosevelt’s last days in the White House, Johnson got his shot. The possibility of a black heavyweight champion of the world called into question many of the racist norms of the athletic paradigm in place.

* Perhaps most fundamentally, leaders of the New York City public schools system created the first organized athletic league for American elementary, middle, and high school students — the Public Schools Athletic League (PSAL). The PSAL courted TR, and it considered how to serve both boys and girls. Thus a juxtaposition that we take for granted today — that of the “student athlete” — had its start here. From its epicenter in NYC during the Strenuous Era, interscholastic sports boomed across the country.

Roosevelt deserves a lion’s share of the credit, or blame (depending on one’s opinion of sports in America), for the rise of modern sports. Sure, Progressive reforms, Social Darwinist fears, and an international Muscular Christianity movement, among other factors, fueled this sports revolution. Changes had been decades in the making. And strangely, Roosevelt did not even like baseball. But Roosevelt occupied the presidency of the United States during this critical era.

As president, Roosevelt participated in, commented on, and theorized about athletics more than any other US president, before or after. What’s more, Roosevelt’s articulation of “The Strenuous Life” translated for many Americans these broad societal changes into personal marching orders.

Making his role even more significant, Roosevelt was on his own fascinating athletic odyssey at the same time — one that reporters chronicled in a fanatical fashion.

The athletic quest had begun when TR took up, as a child, his father’s challenge to defeat a life-threatening medical condition. “Theodore, you have the mind, but you do not have the body,” father challenged son. “Without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body.” Roosevelt boxed at Harvard and built a wrestling room in the New York governor’s mansion. He micromanaged his children’s sports pursuits, always concerned that they develop where he had struggled. He received fighting lessons in the White House. The final stop on Roosevelt’s athletic journey was a two week visit to Jack Cooper’s Health Farm in 1917. There Roosevelt jogged and jiggled, strained and stretched. He pushed himself to a point of joyful exhaustion. Even at fifty-eight years old, Roosevelt was still in training for something. Perhaps it’s this image of Roosevelt-the-aging-jogger that resonates closest to home for modern Americans.

Roosevelt’s America was a place ripe for athletic development. Industrialization and urbanization, now unleashed for three decades, had changed the way that Americans lived and worked. Cities were dirty, crowded places. Corporations in some communities seemed more powerful than the state. Factory work, while dangerous, was boring, and it stole from men and women the physical and emotional benefits that agricultural work had given most Americans half a century before. Doctors began seeing more cases of neurasthenia, a rather amorphous condition that often included: “headaches, backaches, worry, hypochondria, melancholia, digestive irregularities, nervous exhaustion, and ‘irritable weakness.’” Basically, Americans seemed to have every sign of economic progress and technological development in their midst, but instead of flourishing they were falling apart.

The Progressive reformers of this era worked to fix all manner of problems. The general belief was that society no longer worked; the nation’s (and state’s and city’s) institutions needed to be rebuilt given the “increasingly urban, industrial, and ethnically diverse society” of the United States at the turn of the century. The Progressives were nothing if not ambitious. They targeted political corruption, overcrowding, unfair monetary policy, drunkenness, illiteracy, corporate greed, and a basic lack of hygiene, just to name a few.

Alice Roosevelt once famously said of her father: “[He] always wanted to be the corpse at every funeral, the bride at every wedding and the baby at every christening.” Yes, Roosevelt knew how to be the center of attention. He had a near endless supply of energy and ideas. There was no topic on which he demurred. And his opinions — they never ran out. In fact, it was as if a pair of opinion-producing rabbits lived deep within Roosevelt’s core, always reproducing. So, of course Roosevelt had something to say about athletics in America. He had something to say about everything!

But there’s more to it than that. As his daughter might have said had she considered the matter further, Theodore Roosevelt most certainly wished that he could have been the fighter at every championship bout. He would have relished being the quarterback at every big game. But it never happened. As Roosevelt admitted, “I have always felt that I might serve as an object lesson as to the benefit of good hard bodily exercise to the ordinary man. I never was a champion at anything.”

Still, he kept striving right to the end. That was the Strenuous Life. And through the struggle, Roosevelt ended up shaping the very athletic world that he could never quite conquer himself.

Adapted from The Strenuous Life: Theodore Roosevelt and the Making of the American Athlete by Ryan Swanson. Copyright 2019. Available from Diversion Books.