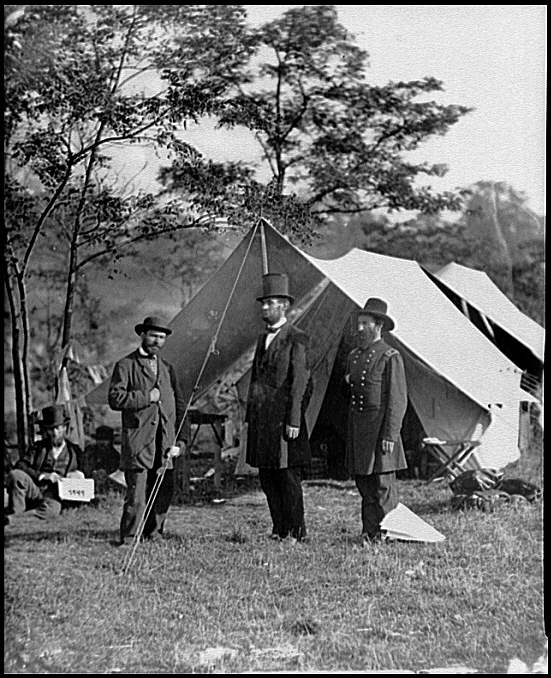

Even though he had no military training, Lincoln quickly rose to become one of America’s most talented commanders.

-

Winter 2009

Volume58Issue6

On July 27, 1848, a tall, raw-boned Whig congressman from Illinois rose in the House of Representatives to challenge the Mexican War policies of President James K. Polk. An opponent of what he considered an unjust war, Abraham Lincoln mocked his own meager record as a militia captain who had seen no action in the Black Hawk War of 1832. “By the way, Mr. Speaker, did you know I am a military hero?” asked Lincoln. “Yes, sir . . . I fought, bled, and came away” after “charges upon the wild onions” and “a good many struggles with the musketoes.”

Lincoln might not have indulged his famous sense of humor in this fashion had he known that 13 years later he would become commander in chief in a war that turned out to be 47 times more lethal for American soldiers than that with Mexico. On his way to Washington in February 1861 as president-elect of a disintegrating nation, he spoke far more gravely. He looked back on another war, which had given birth to the nation that now seemed in danger of perishing from the Earth. In a speech to the New Jersey legislature at Trenton, Lincoln recalled the story of George Washington and his tiny army, which had crossed the ice-choked Delaware River in a driving sleet storm on Christmas night of 1776 to surprise the Hessians in Trenton. “There must have been something more than common that those men struggled for,” said the president-elect. “Something even more than National Independence . . . something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world for all time to come. I am exceedingly anxious that the Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made.”

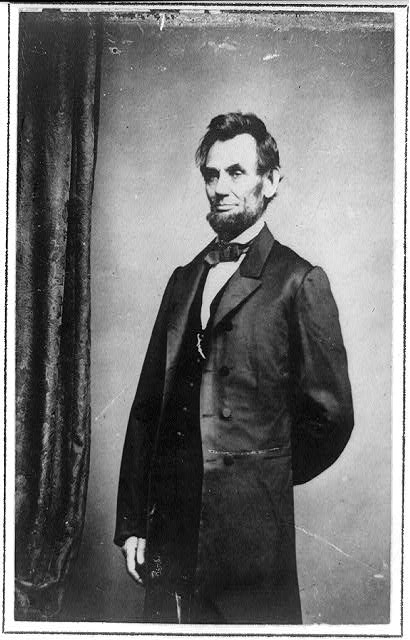

Lincoln faced a steep learning curve as supreme commander in the war that broke out less than two months after he spoke at Trenton. He was also painfully aware that his adversary, Jefferson Davis, was much better prepared. A West Point graduate, Davis had fought bravely as colonel of a Mississippi regiment in Mexico and also served as an excellent secretary of war from 1853 to 1857—while Lincoln’s only military experience was his combat with mosquitoes in 1832. Lincoln possessed a keen analytical mind, however, and a fierce determination to master any subject to which he applied himself, a trait that can be traced to his childhood.

“Among my earliest recollections,” Lincoln told an acquaintance in 1860, “I remember how, when a mere child, I used to get irritated when anybody talked to me in a way I could not understand.” He recalled “going to my little bedroom, after hearing the neighbors talk of an evening with my father, and spending the night walking up and down, and trying to make out what was the exact meaning of some of their, to me, dark sayings. I could not sleep . . . when I got on such a hunt after an idea, until I had caught it. . . . This was a kind of passion with me, and it has stuck by me.” Later in life he mastered Euclidean geometry on his own for mental exercise. As a largely self-taught lawyer, he further honed these qualities of mind. He was not a quick study but a thorough one.

Several contemporaries testified to the slow but tenacious qualities of Lincoln’s mind. The mercurial editor of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley, noted that Lincoln’s intellect worked “not quickly nor brilliantly, but exhaustively.” Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon sometimes expressed impatience with Lincoln’s deliberate manner of researching or arguing a case, but conceded that his partner “not only went to the root of the question, but dug up the root, and separated and analyzed every fiber of it.” Lincoln also focused intently on a case’s central issue, refusing to be distracted by secondary questions. Another lawyer noted that Lincoln would concede nonessential points to an opponent in the courtroom, lulling him into complacency. But “by giving away six points and carrying the seventh he carried his case . . . the whole case hanging on the seventh. . . . Any man who took Lincoln for a simple-minded man would very soon wake up with his back in a ditch.”

As commander in chief, Lincoln sought to master the intricacies of military strategy in the same way that he had tried to penetrate the meaning of mysterious adult conversations as a boy. His private secretary John Hay, who lived in the White House, often heard the president walking back and forth in his bedroom at midnight as he digested books on the science of war. “He gave himself, night and day, to the study of the military situation,” Hay later wrote. “He read a large number of strategical works. He pored over the reports from the various departments and districts of the field of war. He held long conferences with eminent generals and admirals, and astonished them by the extent of his special knowledge and the keen intelligence of his questions.” By 1862, Lincoln’s grasp of strategy and operations was firm enough almost to justify historian T. Harry Williams’s assertion that “Lincoln stands out as a great war president, probably the greatest in our history, and a great natural strategist, a better one than any of his generals.”

This encomium is misleading in one respect: Lincoln was not a “natural strategist.” He worked hard to master the subject, just as he had done to become a lawyer. He had to learn the functions of a commander in chief on the job. The Constitution and the course of American history before 1861 did not offer much guidance. Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution states simply: “The president shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the States.” But the Constitution nowhere defines the powers of the president as commander in chief.

Nor did the precedents created by Presidents Madison and Polk in the War of 1812 and the Mexican War provide Lincoln with much guidance in a far greater conflict that combined the most dangerous aspects of an internal war and a war against another nation. In a case arising from the Mexican War, the Supreme Court ruled that the president as commander in chief was authorized to employ the Army and Navy “in the manner he may deem most effectual to harass and conquer and subdue the enemy.” But the Court wisely did not set out to define “most effectual” and seemed to limit the president’s power by stating that it must be confined to “purely military matters.”

The vagueness of these definitions and precedents meant that Lincoln would have to establish most of his war-making powers for himself. He proved to be a more hands-on commander in chief than any other president, performing or overseeing five wartime functions, in diminishing order of personal involvement: policy, national strategy, military strategy, operations, and tactics.

As president and leader of his party, as well as commander in chief, Lincoln was principally responsible for shaping and defining policy. From first to last that policy was to preserve the United States as one nation, indivisible, and as a republic based on majority rule. In May 1861, Lincoln explained that “the central idea pervading this struggle is the necessity that is upon us, of proving that popular government is not an absurdity. We must settle this question now, whether in a free government the majority have the right to break up the government whenever they choose.” Secession “is the essence of anarchy,” he said on another occasion, for if one state may secede at will, so may any other until there is no government and no nation. In the Gettysburg Address, he offered his most eloquent statement of policy: the war was a test whether the nation conceived in 1776 “might live” or would “perish from the earth.” The question of national sovereignty over a union of all the states was nonnegotiable. No compromise between a sovereign United States and a separately sovereign Confederacy was possible. This issue “is distinct, simple, and inflexible,” he said in 1864. “It is an issue which can only be tried by war, and decided by victory.”

Lincoln’s frequent statements of this policy were themselves distinct and inflexible. And policy was closely tied to national strategy. Indeed, in a civil war, whose origins lay in a political conflict over the future of slavery and a political decision by certain states to secede, policy could never be separated from national strategy. The president shared with Congress and key cabinet members the tasks of raising, organizing, and sustaining an army and navy, preventing foreign intervention, and maintaining public support for the war—all of which depended on his people’s identification with the purpose for which the war was fought. And neither policy nor national strategy could be separated from military strategy.

Some professional Army officers did in fact tend to think of war as “something autonomous,” and they deplored the intrusion of politics into military matters. Soon after he came to Washington as general in chief in August 1862, Major General Henry W. Halleck began complaining (privately) about “political wire-pulling in military appointments. . . . I have done everything in my power here to separate military appointments and commands from politics, but really the task is hopeless.” If the “incompetent and corrupt politicians,” he told another general, “would only follow the example of their ancestors, enter a herd of swine, run down some steep bank and drown themselves in the sea, there would be some hope of saving the country.”

But Lincoln could never ignore the political context in which decisions about military strategy were made. Like French premier Georges Clemenceau a half-century later, he knew that war was too important to be left to the generals. In a highly politicized and democratic society where the mobilization of a volunteer army was channeled through state governments, political considerations inevitably shaped the scope and timing of strategy and even of operations. As leader of the party that controlled Congress and most state governments, Lincoln as commander in chief constantly had to juggle the complex interplay of policy with national and military strategy.

The slavery issue exemplified this interplay. The goal of preserving the Union united the Northern people, including border-state Unionists. The issue of slavery and emancipation divided them. To maintain maximum support, Lincoln initially insisted that the contest was solely for preservation of the Union and not a war against slavery. This policy required both a national and a military strategy of leaving slavery alone. But the slaves refused to cooperate, confronting the administration with the problem of what to do with the thousands of “contrabands” who came within Union lines. As it became increasingly clear that slave labor sustained the Confederate economy and the logistics of the Confederate armies, Northern opinion moved toward the idea of making war upon slavery also.

By 1862, a national and military strategy that targeted enemy resources—including slavery—emerged as a key weapon in the Union arsenal. With the Emancipation Proclamation and the Republican commitment to a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery, the policy of war for Union and freedom came into harmony with the national and military strategies of striking against the vital Confederate resource of slave labor. Lincoln’s skillful management of this contentious process was a crucial part of his leadership in the war.

In the realm of military strategy and operations, Lincoln initially deferred to General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, a hero of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War. But Scott’s advanced age, poor health, and lack of energy made it clear that he could not run this war. His successor, George B. McClellan, proved an even greater disappointment. Nor did Henry W. Halleck, Don Carlos Buell, John Pope, Ambrose E. Burnside, Joseph Hooker, or William S. Rosecrans measure up to initial expectations. Their shortcomings compelled Lincoln to become in effect his own general in chief during key campaigns. Lincoln sometimes even became involved in operations planning and offered astute suggestions to which his generals should perhaps have paid more heed.

Even after Ulysses S. Grant became general in chief in March 1864, Lincoln maintained a significant degree of strategic oversight—especially concerning events in the Shenandoah Valley during the late summer of 1864. The president did not become directly involved at the tactical level—though he was sorely tempted to do so when George G. Meade failed to attack the Army of Northern Virginia, trapped with its back to the Potomac River after Gettysburg. At all levels of policy, strategy, and operations, however, he was a hands-on commander in chief who persisted through a terrible ordeal of defeats and disappointments to final triumph—and tragedy.

Adapted from Tried by War by James M. McPherson. ©2008. Reprinted by arrangement with The Penguin Press.