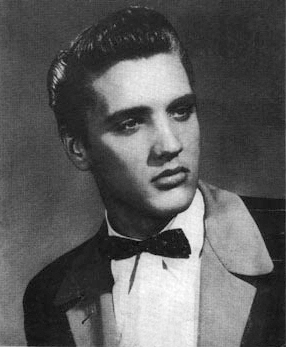

The young rockabilly star autographed each of our forearms.

-

November/December 2024

Volume69Issue5

Editor’s Note: Curtis Wilkie is a retired professor, journalist, and historian of the American South who was the longtime Southern bureau chief for the Boston Globe. Historian Douglas Brinkley observed that, “Over the past four decades no reporter has critiqued the American South with such evocative sensitivity and bedrock honesty as Curtis Wilkie.” Wilkie is the author of numerous books including Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South and Assassins, Eccentrics, Politicians, and Other Persons of Interest: Fifty Pieces from the Road, where a version of this essay first appeared.

In the fall of 1955 Elvis was only one of many stars in the Sun Records orbit. He played second fiddle to another performer, Carl Perkins, and often shared the spotlight with Johnny Cash. When the Sun troupe barnstormed through southern Mississippi in September of that year, Elvis served as a warm-up act before Cash took the stage.

To a tenth-grader, the Sun road show had greater appeal than the one-elephant circuses and cheesy carnivals that drifted through town, but the engagement fell on the same night as our football game. Since Summit High School was small, every able-bodied boy, however uncoordinated, was pressed into duty. Still, the prospect of seeing a live rockabilly performance enjoyed a higher priority than our gridiron contest.

Following the game (which we lost to Cathedral High of Natchez, 41–6), we dressed hurriedly, met our dates, and rushed a couple of miles to the McComb Auditorium, where we watched through an open window as Johnny Cash sang the last number of the night. Disappointed that we had missed most of the show, we three couples squeezed back into the car, drove farther south, across the Louisiana line, into the embrace of “wet” Tangipahoa Parish, where we were able to buy a bottle of cheap wine.

Emboldened, we returned to the auditorium, hoping we might meet the recording artists. The roadies were loading equipment onto a trailer rig when we arrived. As far as we were concerned, Johnny Cash had been the star of the show. He had already departed, we were told, but a pleasant fellow, introducing himself as D.J. Fontana, the drummer for Elvis, volunteered the information that Presley was still around.

Our dates begged to see him. Out of the darkness, the 20-year-old singer materialized. He had slicked-back hair, sideburns, and looked as unprepossessing as a mechanic. Yet he represented our first brush with celebrity, and we were excited by the chance to talk with him. Leaning into a rear passenger’s window, Elvis carried on most of the exchange with the girls.

I remember that he was totally unaffected, indeed charming. Butting into the conversation, I asked Elvis if he were driving his pink Cadillac. One of his records, “Baby, Let’s Play House,” had lyrics — rewritten by Elvis — that included the line “You may drive a pink Cadillac, but don’t you be nobody’s fool.”

“I wrecked it up the road,” he said. (I learned years later from his biographer, Peter Guralnick, that Elvis’s dream car, the pink Cadillac, had actually caught fire and burned en route to a performance in Texarkana in June.) “But I got a new one, a nice yellow one,” Elvis told us, pointing to a gleaming Cadillac with tail fins as imposing as God.

Our encounter with Elvis lasted no more than ten minutes, and before he left, he used a red ballpoint pen to autograph each of our forearms. When I got home, well past my midnight curfew, a scent of alcohol did not help as I pled my case. I explained to my mother that we had been delayed by a meeting with “this famous singer.” As evidence, I produced my arm, where the words Elvis Presley glistened in red script. Mother said she had never heard of Elvis Presley and told me to go in the bathroom and scrub off the stuff.

Since my mother made me wash off his autograph, and I never saw Elvis again, all I have are distant memories of an encounter six high school kids from Summit, Mississippi, had with the rising rockabilly star seven decades ago.