The censure of Andrew Jackson for replacing his Secretary of Treasury raised the question of a president's authority to control the actions of his cabinet members.

-

February/March 2021

Volume66Issue2

Andrew Jackson's accession to the presidency in 1829 was only the second time under the United States Constitution that the reins of power were transferred from one political party to another. The first time was when Jefferson became president in 1801, and although he removed a number of Federalist officeholders, he was in principle opposed to wholesale removals for party reasons. Madison held these principles, as did Monroe and Adams, both of whom refused to take advantage of the opportunity that the Tenure of Office Act of 1820 gave them to appoint their political friends.

When Jackson became president, he reversed this policy. He argued that the former system was undemocratic, for under it “office is considered as a species of property, and government rather as a means of promoting individual interests than as an instrument created solely for the service of the people.” As Jackson conceived of the theory of rotation of office, it was a democratic reform designed to prevent the all too frequent passing of office from father to son and the support of the few at the expense of the many.

In short, Jackson argued for rotation on the grounds that it made the civil service more responsive to the popular will.

Rotation of office in theory was one thing; in practice it was something else. Although Jackson never justified the idea of rotation in terms of partisan politics, some of his more practical-minded supporters did. There is no question but that Jackson's theory of rotation spawned what was later to be called the “spoils system.”

Jackson's opponents vigorously denounced the president's removal power on the grounds that it dangerously increased executive authority, and they argued that it was neither a specifically delegated power nor an inherent part of the president's office. Long suspicious of Jackson's military background, they were fearful that like Caesar he would continually arrogate power to himself until he put an end to the republic. They complained constantly of the “reign of King Andrew ľ” and called themselves “Whigs” after the English party that had opposed monarchical authority in the eighteenth century.

All efforts to check the president's power of removal, by making him accountable to the Senate and giving Congress the right to prescribe the tenure of officeholders, proved futile, however; finally, the opposition stopped when the Whigs adopted the system upon assuming power in 1840.

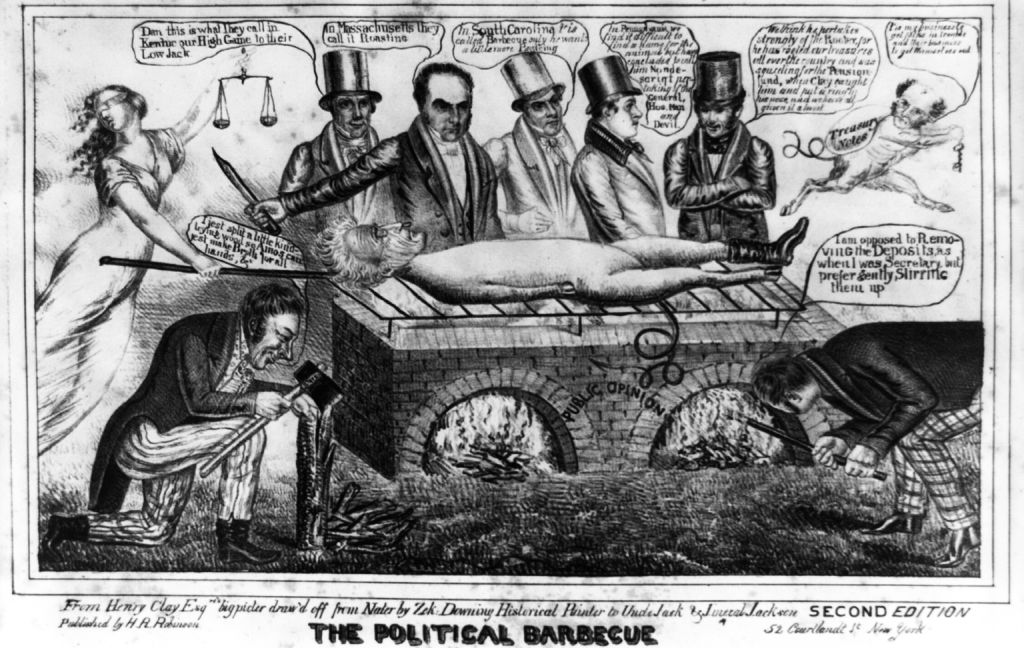

The Removal of the Deposits from the Second Bank and the Censure of President Jackson

The most significant confrontation between Jackson and Congress came when the President removed William J. Duane as secretary of Treasury. The specific episode was not part of the broader debate over Jackson's rotation policy, for Duane had received his appointment from Jackson. Rather, it raised the complicated question of the president's authority to control the actions of his cabinet members and to fire them.

When Jackson vetoed the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States in July, 1832, the Whigs, under Henry Clay's leadership, made it the leading issue of the presidential election of 1832. Jackson, however, won a decisive victory and interpreted it as a popular mandate for further action against the bank by removing the federal deposits from it. This meant spending the federal money in the bank to meet government expenses and depositing all future income in state-chartered or “pet” banks. Jackson justified this action on the grounds that the bank had used its enormous wealth, much of which had been acquired through the use of government funds, to influence congressmen and other government officials, as well as the outcome of the presidential election.

The problem was that the president, personally, did not have the authority to remove the deposits. The act creating the Second Bank of the United States in 1816 had clearly vested this authority in the secretary of the Treasury. According to the act, “the deposits of the money of the United States ... shall be made in said bank or branches thereof, unless the Secretary of the Treasury shall at any time otherwise order and direct."

The Whigs were opposed to Jackson's policy of removing the deposits, arguing that the money was safe and useful in the Second Bank of the United States and would not be so in the state banks. This point of view was shared by Louis McLane, Jackson's secretary of the Treasury as his second term began. McLane, however, agreed to resign, becoming secretary of state, and on June 1, 1833, William J. Duane of Pennsylvania was appointed secretary of the Treasury.

Much to Jackson's chagrin, Duane also questioned the wisdom and legality of removing the deposits. He suggested, instead, a congressional inquiry into the matter. Jackson rejected this idea and tried by means of a series of letters and conferences to bring Duane around to his point of view. But Duane proved intransigent; he also refused to resign. On September 18, Jackson read to his cabinet a paper (drafted by Attorney General Roger Brooke Taney) in which he listed his reasons for wanting a removal of the deposits and in effect said that cabinet members were personally responsible to him for their actions. When Duane remained adamant, he was removed and re. placed by Taney as acting secretary of the Treasury, who promptly began to place the federal deposits in the hands of the state banks chosen for that purpose.

In his annual message of December 3, 1833, Jackson assumed full responsibility for the removal of the deposits. The Senate responded on December 11 by a written resolution calling for the paper he had read to the cabinet on September 18. Jackson refused to comply on the following grounds:

The Whig response was that under the Constitution Congress had been granted control of the public funds, and that the Act of 1789 created the Treasury Department had made it responsible to Congress rather than to the executive. On March 28, 1834, a resolution censuring the President, introduced by Henry Clay, passed the Senate by a 26-to-20 vote. It stated:

The Senate also refused to confirm Taney's appointment as secretary of the Treasury.

In reply, Jackson issued a solemn protest on April 15, 1834. In it he argued that his public censure was unconstitutional, for the resolution censuring him indicated that he had committed a high crime, and that if this were true he should have been impeached, which was the only way provided by the Constitution for Congress to call a chief executive to account, and which would have given him an opportunity to defend himself.

The Senate, however, refused to accept the protest, and no effort was ever made in the House to impeach Jackson despite his vigorous exercise of presidential power and influence. The censuring resolution remained a heated political issue throughout Jackson's second administration, until January 16, 1837, when the president's supporters had it expunged from the Senate Journal over the objections of both those who wanted it to remain and those who simply wanted it rescinded.'

Adapted from a longer essay which originally appeared in Presidential Misconduct: From George Washington to Today, edited by James M. Banner, Jr. Published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.