The “divine wind” began in October 1944 as the Japanese defended against MacArthur’s assault on the Philippines. The Americans who witnessed these first attacks were horrified and shaken, but it was only the beginning.

-

Summer 2021

Volume65Issue5

Editor's Note: James P. Duffy, the author of over a dozen books mostly on military history, wrote “No One Returns Alive“ in our Fall 2017 issue about the critical but often-overlooked New Guinea campaign. Jim adapted the following essay from his most recent book, Return to Victory, about MacArthur’s campaign to retake the Philippines.

Throughout Japan’s history, its warriors were often eager to sacrifice their lives for their emperor. Suicide missions by Japanese aircraft pilots and officers on midget submarines were not an entirely new phenomenon by the time the Philippines became the number one target of the Allies in the fall of 1944. There were several instances of pilots attempting to crash their planes into US warships with some limited success. None of these were planned or ordered by competent commanders, but were spur-of-the-moment decisions made by the pilots themselves. Since none of them survived, we have no clear understanding of why they chose to do what they did other than to die for their emperor.

One of the earliest recorded suicide missions to attack American ships was on September 13, 1944, although there is no indication it was successful. Several Imperial Army pilots belonging to the 31st Fighter Squadron on the Philippine island of Negros decided on their own to strap 100kg bombs to two of their aircraft. Taking off just before dawn, First Lieutenant Takeshi Kosai and the second pilot vanished after takeoff. Since there were no reports of a plane crashing into American Navy warships that day, probably both fell victim to Allied patrol aircraft.

The turn to officially sanctioned suicide missions by Japanese pilots was a sure sign of desperation. Attacks on US Navy carrier task forces were proving unproductive since these valuable targets were defended by a large array of ships with antiaircraft guns as well as their own aircraft flying defensive patrols above them.

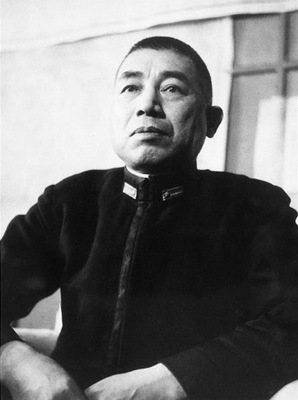

The man responsible for sending so many Imperial Navy pilots — for most suicide pilots were navy flyers — to their deaths was Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi. In July 1944, Onishi was already advocating what he called “body-crashing” into Allied ships and B-29 bombers. He claimed that pilots who would conduct such attacks were “god-like soldiers.”

Onishi called these men “shimpu,” although they became more infamous to Westerners as “kamikaze.” Both versions originate with Japanese translations of “divine wind,” based on two incidents occurring in the 13th century. In the first, the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, sent an invasion fleet estimated between five hundred and nine hundred ships carrying forty thousand men to force the Japanese emperor to submit to rule by the Mongols. After initially defeating the defending Japanese troops, the Mongols withdrew to their ships anchored in Hakata Bay to prepare for the next day. However, during the night a powerful typhoon struck the bay and sank most of the Mongol ships, taking tens of thousands of soldiers to the bottom. The few remaining ships sailed away.

The khan ordered a new and larger fleet built for his next attempt to conquer Japan. In the meantime, the Japanese were busy constructing seven-foot-high walls along the coast to prevent an invasion. In 1281 over four thousand Mongol ships with over one hundred thousand troops entered Hakata Bay and searched for a landing site. They searched in vain for a place to go ashore, until on August 14 they once again fell victim to a large typhoon that devastated the fleet, forcing the surviving ships to withdraw. In Japanese mythology, the two storms were a divine wind sent by the gods in response to the prayers of the Japanese emperor.

Once Onishi formalized the suicide missions, the Tokyo propaganda machine began referring to the pilots as the “Divine Wind,” a force that would once again drive away an enemy fleet attacking the homeland. Despite opposition from several other admirals, Onishi wasted no time when he arrived on Luzon as the new commander of the First Air Fleet charged with defending against MacArthur’s impending assault. Shocked at finding his fleet had been reduced by enemy air strikes to only about one hundred operational aircraft, the short, stocky naval officer with a reputation for abrasive manners decided he knew how to best use those limited resources. Instead of fighting off enemy aircraft or attacking enemy ships, he would urge his pilots to slam their aircraft onto the flight decks of American aircraft carriers.

Two days after arriving at his new post from Tokyo, Onishi had himself driven to Mabalacat Airfield, part of the former American Clark Field Air Base fifty miles northwest of the capital of Manila. There he met with Commander Asaichi Tamai, the executive officer of the 201st Air Group, Captain Rikihei Inoguchi, senior staff officer of the First Air Fleet, and several senior officers of the air group.

The admiral began in a serious low tone, telling these men what they already knew: the situation for Japan was grave. The American ships reported off the coast of Leyte were a clear indication that MacArthur was determined to fulfill his pledge to the Filipino people to return and drive the Japanese out. He then explained that the fate of the empire rested on the success of the shō-go (Victory) plan, the defense of the Philippines. He told them that what remained of Japan’s main battle fleets were even then sailing toward the Philippines from their anchorages. The First Air Fleet would have the privilege of providing air cover for the approaching warships since they no longer had operational carriers capable of doing so. The men in the room and their pilots were to “neutralize” the enemy carriers for at least one week. This was to give Vice Admiral Kurita’s fleet with the world’s two largest battleships, Musashi and Yamato, time to reach Leyte Gulf and destroy the American invasion forces.

As they listened to Onishi, the men wondered how they were going to accomplish such a mission with barely one hundred planes against hundreds of enemy aircraft and an unknown number of powerful aircraft carriers. Then the admiral reached the heart of his message. It was his opinion that the only way they could stop the enemy now was through suicide attack units. He proposed to attach 550-pound bombs to Zero fighters and crash them onto the decks of the American carriers to temporarily put them out of service. And so, on that day, the First Shimpu Special Attack Corps was born.

When asked, the pilots of the 201st Air Group all volunteered for the suicide missions. In coming months, kamikaze pilots would be young and inexperienced with minimal training, but enough to enable them to take their bomb-laden aircraft off the ground, fly to a target, and aim the craft at the target’s flight deck. But the pilots of the 201st were among the best the Imperial Navy had left after losing nearly a thousand of them the previous June in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, which American pilots called “the great Marianas turkey shoot.”

See “The Marianas Turkey Shoot" in the October 1967 American Heritage by Admiral J. J. Clark, who commanded Task Group 58.1 in that battle.

Three days after Onishi’s visit to the 201st, the first formal kamikaze mission took off from Mabalacat Airfield in search of the enemy fleet reported approaching Leyte. Commanded by Lieutenant Yukio Seki, they spent several days searching for the enemy without success. On October 25, six Zero fighters that had been stripped of all unnecessary equipment but with a 500-pound bomb attached, along with four Zeros flying escort, found a group of American escort carriers off Samar and attacked.

In the resulting forty-minute melee, one escort carrier, St. Lo, had its flight deck penetrated by one of the bomb-laden Zeros. The bomb exploded in the hangar belowdecks where sailors were busy refueling and rearming several aircraft. Gasoline was set ablaze which resulted in a series of explosions, including in the bomb storage magazine. In thirty minutes the burning ship sank, taking with it 113 of its 889 crew. An additional thirty died from their wounds. Two other escort carriers received damage serious enough to take them out of the war: one, Kitkun Bay, for two months; the other, Kalinin Bay, never returned to combat.

American forces continued to encounter kamikazes. During the invasion of Mindoro, code-named Love III, one of MacArthur’s favorite ships — the cruiser Nashville — was attacked as it made its way with the rest of a convoy to the southwest end of the island. Navy staff first identified the northeast region of Mindoro as the likely place to land from a tactical standpoint, but this was soon discarded when the planners realized the invading forces would be subject to relentless attacks from enemy land-based aircraft on Luzon. So instead, they selected the port town of San Jose on the island’s southwest coast near Mangarin Bay, the island’s best anchorage and the location of a seaplane base.

On the evening of December 12, the Western Visayan Attack Force sailed from the east coast of Leyte heading south and west through the Surigao Strait toward the Mindanao Sea and then the Sulu Sea. Rear Admiral Arthur D. Struble commanded the force comprising thirty tank-landing ships, thirty-one infantry landing craft, eight destroyer transports, twelve medium landing ships, seventeen minesweepers, and smaller specialized craft. Nineteen destroyers, one heavy cruiser, twenty-three PT boats, and three light cruisers, including the force flagship Nashville, closely escorted them. Following behind because of their slow speed was a Slow Tow Convoy consisting of an assortment of destroyers, destroyer escorts, tankers, and other vessels carrying fuel and materials required to construct a PT boat base at Mindoro. At a farther distance were six escort carriers each with twenty-four fighters and nine torpedo bombers on board, as well as three battleships, three light cruisers, and eighteen destroyers.

It was nearly 3 p.m. on December 13, when the Western Visayan Attack Force rounded the southern end of Negros and headed toward the Sulu Sea. Unknown to those aboard the armada, Japanese reconnaissance aircraft had been watching and reporting on their progress since nine that morning. They had not yet attacked the enemy ships as their intelligence officers awaited reports to determine where the Americans were going. Also, unknown to the men on the ships, three suicide pilots took to the air in “Vals” (dive bombers) from an airfield on Cebu, accompanied by a seven-fighter escort-and were headed in their direction.

At 2:57, a lookout aboard the Nashville reported a Val coming in at five thousand feet from the starboard side with bombs clearly visible attached to both wings. At first it appeared to be headed for another ship in the convoy, but then suddenly turned directly at the cruiser as anti-aircraft guns fired relentlessly at the speeding plane. Apparently aiming for the ship’s bridge, the plane’s right wing hit a 40mm anti-aircraft gun mount and smashed instead amidships. The aircraft’s bombs exploded, as did the ammunition of several gun mounts as burning aviation fuel flowed in all directions. One sailor described the cruiser as “a vessel of death and destruction.”

The inferno aboard the Nashville cost the lives of 133 officers and men and wounded 190 others, including General Dunkel, whose injuries were described as “painful but not serious.” Among the dead were Admiral Struble’s chief of staff and General Dunkel’s chief of staff. With the fires extinguished, Admiral Struble transferred his flag to the destroyer Dashiell. The convoy continued toward Mindoro while the Nashville began its long journey to Puget Sound Navy Yard for extensive repairs before rejoining the war.

It was just luck that MacArthur had not joined the convoy, or he might have been wounded or killed in the attack. The Nashville was his favored ship; he thoroughly enjoyed standing on the same bridge where several of the dead and wounded officers were when the kamikaze struck.

Almost a month after taking Mindoro, in January 1945, General MacArthur boarded the cruiser Boise in Leyte Gulf for the trip to Luzon’s Lingayen Gulf. A party comprising staff members from his Tacloban headquarters accompanied him. He made it clear he expected to establish his South West Pacific Area headquarters on Luzon just as soon as his forces secured the beachhead.

The advance force heading toward Lingayen Gulf was under the command of Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf. It contained six battleships – including his flagship California – six cruisers, thirty-three destroyers, twelve escort carriers, six destroyer escorts, ten destroyer transports, two fleet tugs, one seaplane tender, eleven LCI gunboats, and seventy other warships including thirty minesweepers. Two days earlier, on January 2, the first echelon of what grew to over 160 ships departed Leyte Gulf at noon.

The following morning as they rounded Negros and entered the Sulu Sea, several enemy aircraft that were likely Val dive-bombers flown by kamikaze pilots attacked the ships. Two of the aircraft, each with a massive bomb strapped below, zeroed in on the fleet oiler Cowanesque. The ship’s antiaircraft and machine guns shredded both planes before they could reach their target. One was close enough that its violent explosion sprayed fuel and fragments over the ship’s deck. Among the debris that landed on the oiler was an unexploded bomb that could have caused not only considerable damage but also increased fatalities. The crew raced to extinguish the fire and pushed the bomb overboard. Two members of the ship’s crew died in the attack and two others received injuries. With the damage quickly repaired, the oiler continued on its mission.

Despite their best efforts, the Japanese were having a difficult time attacking Oldendorf’s massive war fleet. He had divided the fleet into two sections, each built around a group of escort carriers that worked tirelessly keeping dozens of fighters in the sky above them as combat air patrol to fend off the enemy aircraft. The attacking planes included 120 from various Luzon airfields. Unable to penetrate the Allied air cover, Japanese pilots were forced to fly time- and fuel-consuming circuitous routes in order to approach the fleet from the west.

Shortly after 5 p.m. on January 4, seventeen miles off the entrance to Mindoro Strait, a “Betty” twin-engine Mitsubishi medium bomber that had escaped detection by ship radar and the dozens of lookouts on the escort carrier Ommaney Bay raced toward the ship’s island. It ricocheted off the island and smashed onto the flight deck. One of the Betty’s two bombs penetrated to the hangar deck and exploded, as the second did the same in the forward engine room. Fully fueled planes parked in the hangar deck soon created a nightmare series of explosions and fuel fires like monstrous Molotov cocktails. A ruptured water main reduced water pressure for firefighting, while power and communications throughout most of the ship were lost. Overheated .50-caliber machine-gun bullets firing off in every direction further hampered the crew’s efforts to save their ship.

Thick, oily, black smoke poured into the evening sky as escort ships sped to the carrier’s assistance. Several destroyers approached alongside, but the intense heat and exploding ammunition, including torpedo warheads, forced them back. The best they could do was to lower whaleboats to pluck survivors from the sea.

At ten minutes to six, Captain Howard Leyland Young issued the abandon ship order, but by then most of the surviving crew members had already escaped the flames and explosions. The carrier was finally sunk by torpedoes from the destroyer Burns. Ninety-five sailors died in the attack, including two from a nearby destroyer.

Aboard the cruiser Boise, which had been unsuccessfully attacked by an enemy submarine, General MacArthur realized that the attacks on Luzon airfields by land-based planes of the Allied air forces were having less than the desired effect on the enemy suicide formations. Late on the fourth, the same day Ommaney Bay sank, he requested Admiral Halsey, who had been launching his Third Fleet air units against enemy airfields on Formosa, to target Japanese airfields on Luzon north of Clark Field.

The following day, January 5, while Halsey’s fleet was recalibrating its plans and the Allied airfields on Mindoro were temporarily closed due to extremely wet weather conditions, the Japanese launched a series of kamikaze attacks on the Allied fleet now sailing north off the west coast of the Bataan Peninsula, heading unmistakably for Lingayen Gulf. Previously these attacks had been hit or miss, but the large armada sailing along the coast demanded action that was more concentrated. With the bulk of land-based and fast carrier aircraft unavailable that morning, the combat air patrols from Oldendorf’s escort carriers were the main line of defense as kamikaze planes and their fighter escorts swept in on the ships.

Of the aircraft attacking that evening, which seemed to be the favored time for suicide attacks, only two survived. Five of the kamikazes managed to break through the American patrol planes and the fierce antiaircraft fire from the ships. One smashed into Rear Admiral Theodore E. Chandler’s flagship, the heavy cruiser Louisville. The direct hit on the main battery killed one man and injured seventeen others including the ship’s commander, Captain Rex LeGrande Hicks. A second heavy cruiser, HMAS Australia, suffered only slight damage but lost twenty-five crewmen killed and another thirty wounded from the exploding bomb hanging from a suicide plane. Both ships managed to continue their mission.

MacArthur watched the action around his ship from an antiaircraft battery near the Boise’s quarterdeck. As his staff drifted away to attend to other duties, the commander remained at the rail as if glued to the spot. In a way, he was, for he was searching the eastern horizon for a glimpse at a familiar sight on Corregidor and Bataan.

As the American fleet continued its passage and began to enter Lingayen Gulf, Japanese suicide missions increased, ultimately sinking five ships and damaging sixteen others. The Boise, with MacArthur aboard, was targeted but survived a near miss by an enemy fighter pilot determined to die for his emperor. Another narrow escape was the surprise surfacing of a Japanese midget submarine that fired two torpedoes at the Boise. The cruiser managed to avoid being struck. The enemy craft paid for its failed attempt when a nearby destroyer rammed it and sent it and its crew to the bottom.

A Zero carrying a 500-pound bomb, and already in flames from antiaircraft fire, raced at the battleship New Mexico from its stern. The burning plane crashed into the ship’s navigation bridge. The explosion knocked out two antiaircraft guns and killed thirty men, including the battleship’s commander, Captain Robert Walton Fleming, who was said to have asked a crew member who came to his aid if the ship was all right. After being told it was, the captain died.

Also among the dead was Lieutenant General Herbert Lumsden of the British Army. Lumsden, who had fought in the First World War and commanded an armored corps against Rommel in North Africa, was appointed Winston Churchill’s personal representative to MacArthur’s headquarters in November 1943. Lumsden and MacArthur had become close friends during that time.

MacArthur wrote a personal message to the British prime minister informing him of Lumsden’s death and praising his service to the Allied cause. He closed with the comment that his sorrow over Lumsden’s death was “inexpressible.” The highest-ranking British officer to die in combat during the war, he was buried at sea.

The Americans who witnessed these first kamikaze attacks were horrified and shaken, but it was only the beginning. Suicide missions by Japanese pilots had become a vital part of the defense of the Philippines, followed later at Okinawa and other battles. Although accurate numbers are hard to come by, it is believed that at least three thousand Japanese pilots gave their lives for the emperor in this way. Some three hundred Allied ships received some level of damage from the planes, with as many as 47 sinking through the end of the war.