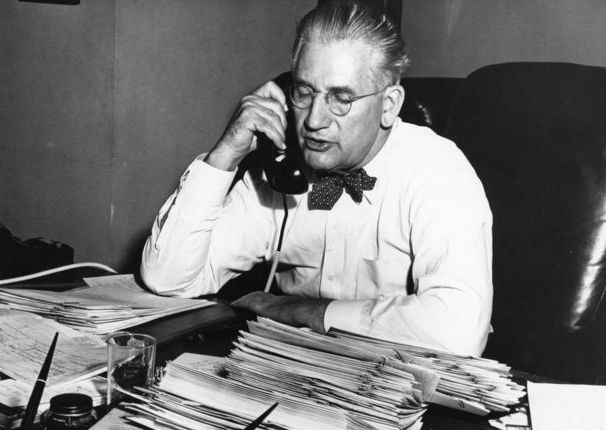

Paul Douglas was 50 years old when he left a career in politics to join the Marines at the outset of World War II, earning Purple Hearts at Peleliu and Okinawa.

-

Spring 2023

Volume68Issue2

The average age of a United States Marine Corps recruit is 21. When Paul Douglas enlisted in 1942, he left behind his wife, his child, and his career and reported to the Parris Island Marine Corps Recruit Depot in South Carolina at the ripe age of 50.

Even though thousands of visitors have walked the halls of the Douglas Visitors' Center, very few know the story of the man behind the name, who became the oldest recruit in the history of Parris Island.

Born in 1892, Douglas embarked on a career as an economics professor, teaching at various universities across America from 1916 to 1942. In 1939, he ran for the Chicago City Council and won.

By 1942, Douglas had made many acquaintances in high places, including Frank Knox, an associate he befriended during his tenure at the Chicago Daily News who later became Secretary of the Navy. With a little help from Knox, Douglas enlisted in the United States Marine Corps as a private, five months after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, as the country was plunged into a Second World War. He had wanted to see combat and fight for his country, so, with his connections in the Naval Service, the Marine Corps became the most logical choice.

The 50-year-old famed economist, professor, and politician found himself commanded by drill instructors whom he was old enough to have fathered. After completing boot camp, Douglas proudly wrote “I found myself able to take the strenuous boot camp training without asking for a moment's time out and without visiting the sick bay.”

After impressing commanding officers during boot camp, he was assigned to the personnel-classification section on Parris Island. With influence from his connections in the Roosevelt administration, three weeks later, he passed a test to be promoted to corporal, and one month after that, staff sergeant. Following a recommendation from his commanding officer (and a strong recommendation from his old friend Frank Knox), Douglas was commissioned as a captain in the Marine Corps after seven months as an enlisted Marine.

During the battle of Peleliu, while serving as the division adjutant to the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, Captain Douglas made trips to the front lines to evacuate wounded and dead men. During one of these trips, he saw that the men were in desperate need of flamethrowers and rocket-launcher ammo. He swiftly returned to the rear and hand-delivered the men the ammo under heavy mortar and small-arms fire. For these heroic actions, he would be awarded the Bronze Star. Later in the campaign at Peleliu, Douglas came under fire and was hit by a piece of shrapnel, for which he received his first Purple Heart.

He went on to serve in the battle of Okinawa, often being remembered by Marines for running around the battlefield with the vigor of a much younger Marine. He was promoted to major during that battle. Pfc. Paul E. Ison said that it was after he had pulled his demolition team aside to assist in resupplying ammo to the front lines that he noticed Douglas had been injured.

He had been hit by machine-gun fire in his left forearm and was evacuated by the men that he had risked his life to assist. After being hit, he used his uninjured hand to take off his major's insignia so that he wouldn’t receive special attention.

Ison said, “If I live to be 100 years old I will never forget this scene. There, lying on the ground, bleeding from his wound, was a white-haired Marine major. He had been hit by a machine gun bullet. Although he was in pain, he was calm and I have never seen such dignity in a man. He was saying ‘Leave me here. Get the young men out first. I have lived my life. Please let them live theirs.'”

Douglas expressed passionate interest in returning early to his men to continue serving on the front line. But he was hospitalized in San Francisco and subsequently moved to Bethesda, Maryland, where it took more than 14 months for him to be dismissed from the hospital. He was medically retired from the Marine Corps, only regaining partial use of his left hand.

Noting his unusual bravery, an officer who served under Douglas said, “No one could keep the major out of the front lines. He loves his boys and was right in there with them all the time.”

Under his command, it was common to see Douglas waiting in the back of the chow-hall line while fellow officers skipped to the front. Also, he picked up garbage so that young Marines wouldn’t have to, and he did anything else he could do to assist the men under him. All accounts from those who served with him reveal that he was greatly admired by his Marines.

Commenting on the importance of honoring Douglas and his actions by dedicating a building to him, Dr. Stephen Wise, the director of the Parris Island History Museum, stated, “It’s important to remember Marines who made an impact and influenced the Marine Corps in a positive direction. Douglas was the oldest individual to go through Parris Island. He could have stayed safely on ship, and he chose not to; we want people to remember these men and their actions.”

Because of his brave actions under fire and overall unselfish service, Douglas was promoted to lieutenant colonel a year after he retired in January of 1947. After returning to Chicago as a war hero, Douglas won a spot as Illinois state senator in 1949.

During the campaign, the opposing candidate refused to debate him, so Douglas sat down and debated an empty chair, switching chairs to answer for his opponent. He was noted for his support of Dr. Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement and. He served as senator for 18 years until he retired at age 74.

In 1977, Parris Island Visitors' Center was named in Douglas’ honor. His wife, Emily Douglas spoke about the tribute Parris Island had bestowed upon her late husband: “Later in his life, many honors came to my husband. But there is none that would have so touched him, made him so astonished as well as thrilled, as having his name associated here at Parris Island.”

In public office, Douglas continued to advocate for the Marine Corps, and proudly kept the Marine Corps standard displayed in his office.

“All of us have standards by which we measure other men," said Paul E. Ison. "Paul Douglas was one of the finest, bravest, and truest men that I have known during my lifetime. It was an honor to have been associated with him, to have shared danger with him, and to have observed his nobility of character when he was wounded and asked to be left behind so that younger men might live.”