Carter's diplomatic legacy has endured well, though he often struggled to project a convincing aura of strength and accomplishment in office.

-

Winter 2025

Volume70Issue1

Editor's Note: Yanek Mieczkowski is a presidential historian and author of Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970s, Eisenhower’s Sputnik Moment: The Race for Space and World Prestige, and The Routledge Historical Atlas of Presidential Elections. He teaches at the Florida Institute of Technology.

In 1977, Jimmy Carter arrived at the White House with no foreign policy experience, and as the former one-term Georgia governor’s presidency progressed, his diplomacy attracted criticism and seemed to epitomize weakness. By 1980, one poll showed that Americans disapproved of his foreign policy by 82 to 17 percent. Carter’s reputation as a micromanager, blind to the big international picture, prompted West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt to comment that America’s leader “knows everything and understands nothing.” Yet in history’s rearview mirror, Carter’s foreign policy looks better. He presided over four years of peace and bequeathed lasting legacies.

Carter brought a lofty idealism to U.S. foreign policy, wishing to end the Cold War’s fixed gaze on power politics and military might. To improve Third World relations, he secured Senate approval of the Panama Canal Treaties, which he called “a litmus test” of how a superpower should treat smaller nations. By turning control of the Canal Zone to Panama, the agreement improved U.S. relations with Central America.

Another Carter diplomatic initiative involved China. In December 1978, Carter stunned the world by announcing that he would grant diplomatic recognition to Communist China, displacing America’s decades-old relationship with Taiwan. The latter’s supporters fumed at Carter’s move, yet it anticipated China’s rise as a global superpower.

In addition to cultivating new ties, Carter maintained connections with established allies. He reinforced diplomatic breakthroughs that President Gerald R. Ford had forged, continuing the G-7 summits with industrialized allies, where leaders assembled in different host cities and coordinated economic policies. Carter also encouraged change in Eastern Europe. The American delegation he sent to the 1978 Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe urged observance of the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which Ford considered his greatest diplomatic achievement, promising freer movement of people and ideas across the Iron Curtain.

In effect, Carter induced the Iron Curtain to rust, weakening it and encouraging stirrings of independence in Soviet satellites. A little more than a decade later, the Iron Curtain fell, and then the Soviet Union collapsed.

But in the 1970s, the Soviet Union was still formidable, and Carter whipsawed between warm and frigid relations with this Cold War adversary, fostering an image of vacillation and weakness. During the decade, détente—easing tensions with the U.S.S.R.—was in vogue, and in 1979, Carter and Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev signed the SALT II arms control treaty, kissing each other on the cheek when they inked the agreement in Vienna.

The treaty died in the sands of Afghanistan. Six months after the signing, the Soviet Union invaded that country, plunging American-Russian relations into a deep chill. Invoking punitive sanctions, Carter embargoed U.S. grain sales to the U.S.S.R., boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and shelved the SALT II Treaty. Carter worried about Soviet aggression in the Middle East, and in January 1980 he delivered a forceful State of the Union address in which he declared that the U.S. would defend the Persian Gulf. This so-called “Carter Doctrine” has codified America’s commitment to the Middle East ever since.

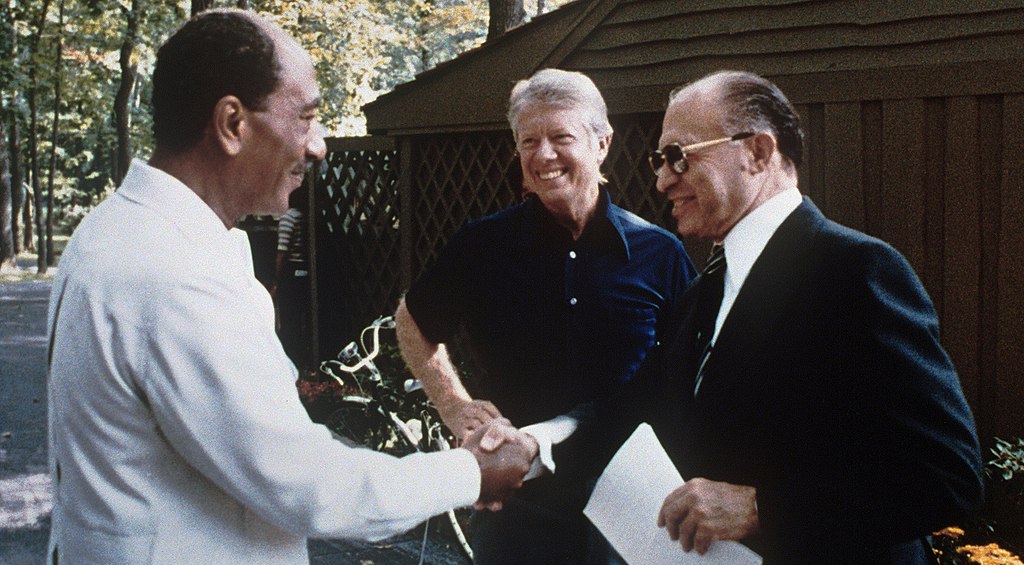

In that region Carter met his greatest success and frustration. In 1978, Carter hosted Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin for peace talks at Camp David. Always one to delve into detail, Carter immersed himself in the nitty-gritty of negotiating, acting as a go-between between the two hardboiled leaders. After twelve historic days, the three men emerged with the Camp David Accords, leading to a peace treaty that they signed on the White House lawn in 1979. That agreement still stands as the most notable breakthrough in Middle East peace since Israel’s 1948 founding.

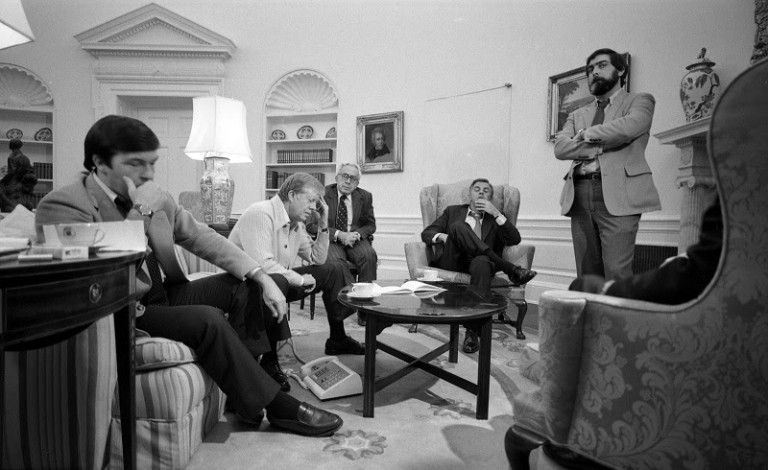

But later in 1979, the volatile region dragged Carter down from triumph to travail. In November, an Iranian mob seized the U.S. embassy in Teheran, taking fifty-two Americans hostage while demanding the return of the exiled Shah of Iran. The crisis paralyzed Carter’s presidency—an image he fostered by spending long hours in the Oval Office agonizing over the hostages. Iran held the Americans captive until Carter left office, releasing them just moments after Ronald Reagan was inaugurated. But in the end, every hostage returned home safely, which Carter considered his signal achievement.

Given the headline-grabbing setbacks of Carter’s last months in office, critics lambasted him as a failed diplomat. U.S.-Soviet relations had deteriorated; global respect for America had plummeted. Yet Carter’s dogged pursuit of peace and diplomatic morality were decent goals that generated a decent record. Only a president of his high idealism could have aimed for breakthroughs in Panama and the Middle East. Moreover, no Americans died in combat during his presidency, and Carter’s actions quietly enhanced America’s strength vis-à-vis the Soviet Union’s, especially with military measures such as his approval of new radar-evading stealth technology. Carter’s 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, awarded more than two decades after he left office, recognized his constructive work in foreign policy.

Where Carter fell short, his wounds were often self-inflicted. He drowned in detail, never trumpeting his deeds in an expansive, majestic way—the crucial concepts of imagery and messaging. These shortcomings provide a trenchant lesson. Time and history may judge a presidential record fairly, but the commander-in-chief must project a convincing aura of strength and accomplishment while in office. Here Carter struggled, never mastering the machinery of successful imagery; nonetheless, his diplomatic legacy has endured well.