With bloody conflicts in so many hot spots around the world, we should remember that the erasures of civilizations are not mere memories from a distant past.

-

November/December 2024

Volume69Issue5

Editor’s Note: Victor Davis Hanson is an American military historian, columnist, classics professor and prolific author. He was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2007 by President George W. Bush. Hanson’s most recent book, The End of Everything: How Wars Descend into Annihilation, from which this essay was adapted, looks at examples in the past of civilizations that were destroyed, reminding us that societies are not immune from the horror of wars of extinction and the erasure of an entire way of life.

There are lots of ways that states and their peoples can vanish from history, and all sorts of causes explain their disappearance. Both nature – earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, plagues, and climate change – and humans sometimes wipe out vulnerable populations. Indeed, entire cultures have often been obliterated, sometimes quickly, sometimes over decades. Rarer is the abrupt wartime destruction of a civilization, a state, or a culture through force of arms, as with classical Thebes, Punic Carthage, Byzantine Constantinople, and the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan. They provide a warning that the modern world, America included, is hardly immune from repeating these tragedies of the past.

The wartime end of everything has usually followed from a final siege or invasion. The coup de grace predictably targeted a capital or the cultural, political, religious, or social center of a state. And the final blow resulted in the erasure of an entire people’s way of life – and often much of the population itself.

Strangely, the transition from normality to the end of days could occur rather quickly. A rendezvous with finality was often completely unexpected. Yet absolute defeat too late revealed long-unaddressed vulnerabilities, as economic, political, and social fissures widened only under wartime pressures. Waning empires rarely wished to accept, much less address, the fact that their once-sprawling domains had been reduced to what the defenders could see from their walls.

Naivete, hubris, flawed assessments of relative strengths and weaknesses, the loss of deterrence, new military technologies and tactics, totalitarian ideologies, and a retreat to fantasy can all explain why these usually rare catastrophic events nevertheless keep recurring – from the destruction of the Inca Empire to the end of the Cherokee nation to the genocide of a populous, vibrant, and Yiddish-speaking prewar Jewish people in Central and Eastern Europe.

The continual disappearance of prior cultures across time and space should warn us that even familiar twenty-first-century states can become as fragile as their ancient counterparts, given that the arts of destruction march in tandem with improvements in defense. The gullibility, and indeed ignorance, of contemporary governments and leaders about the intent, hatred, ruthlessness, and capability of their enemies are not surprising. The retreat to comfortable nonchalance and credulousness, often the cargo of affluence and leisure, is predictable given unchanging human nature, despite the pretensions of a postmodern technologically advanced global village.

Even in our modern age – of transnational wealth, an interconnected global economy, Davos, the United Nations, thousands of non-governmental organizations, a rules-based international order, and majorpower nuclear deterrence – the fates of Thebes, Carthage, Constantinople, and Tenochtitlan are not mere memories from a distant benighted past and thus irrelevant in the present.

Of course, no modern state enslaves the entire surviving population of the defeated – one of the most effective ways in the past of erasing a civilization – in the fashion of Alexander the Great with Thebes, or Scipio Aemilianus with Carthage. And the United States at least is protected by two oceans, a formidable nuclear deterrent of nearly sixty-five hundred warheads, and the most powerful economy and military in history. How then could it be reduced to nothingness by any enemy on the world stage?

Unfortunately, the more things change technologically, the more human nature stays the same – a law that applies even to the United States, which often believes it is exempt from the misfortunes of other nations, past and present. However, there is no certainty that as scientific progress accelerates and leisure increases, and as the world shrinks on our computer and television screens, there is any corresponding advance in wisdom or morality, much less radical improvement in innate human nature.

The besieger of Tenochtitlan, Hernan Cortes, operated on the same principles as did Alexander the Great, some 1,788 years earlier, in assuming that almost all of the Aztecs he stormed would end up as serfs, slaves – or dead. If the world is now intolerant for the most part of slavery, cannibalism, and human sacrifice, nonetheless the tools of genocide – nuclear, chemical, and biological – are far more advanced than ever before. And they are at our fingertips.

The years 1939 to 1945, with their seventy million dead, a mere two decades after twenty million perished in ‘‘the war to end all wars” of 1914-1918, taught us once again that with material and technological progress often comes moral retrogression, a lesson dating back to the seventh-century BC Greek poet Hesiod, who warned in stories such as Pandora’s box that bad behavior brought suffering into the world.

The twenty-first century has already experienced bloody wars in places as diverse as Afghanistan, Chechnya, Crimea, Darfur, Ethiopia, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Niger, Nigeria, Ossetia, Pakistan, Sudan, Syria, the West Bank, and Yemen – all of which followed the end of the millennium genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda. Yet these gruesome conflicts are not even the most likely current flash points that threaten to draw in major powers possessing weapons of mass destruction, including most notably the United States.

In the last few years alone, Russia has threatened to use nuclear weapons against Ukraine, China against Taiwan, Iran against Israel, Pakistan against India, and North Korea against South Korea, Japan, and the United States. Turkey has talked of sending missiles into Athens and Israel, or solving the Armenian “problem” in the manner of its forebears. These are just the threats of bombs and missiles, as we head into the age of gain-of-function pathogens and artificial-intelligence-guided munitions.

The four ancient man-made Armageddons are different from the mysterious disappearances, or the monumental abrupt system collapses, of “lost civilizations” such as the Mycenaeans (ca. 1200 BC) or Mayans (ca. AD 900). They are clearly not the same as smaller extinctions like the mysterious ends of those on Easter, Pitcairn, or Roanoke Islands. Nor are we talking about the gradual, internal decay that incessantly wastes away a nation or empire, such as the dissolution and partial absorption of fifth-century AD imperial Rome by the proverbial barbarians, and its slow metamorphosis into Europe of the so-called Dark and Middle Ages. Nor the political disappearances of state governments or the changing names of peoples, such as the formal end of the nomenclature and political existence of Prussia and Prussians, or Yugoslavia and Yugoslavians. Even the actual destruction of an enemy state – with borders, a government, and a unique history and culture – does not always equate to the genocide of an entire people, although at times a victorious siege certainly can result in mass death driven by racial, ethnic, or religious hatred.

But if states and cultures can be completely obliterated by wartime enemies, then when exactly is a people defined as vanquished or ended? When its nation is formally conquered, occupied, and its citizenry made permanently subservient? Or when a state’s government disappears, its infrastructure is leveled, most of its people killed, enslaved, or scattered, its culture fragmented and soon forgotten, and its space abandoned or given over to another and quite different people?

Of course, nothing ever quite ends, at least in its entirety. Political institutions implode. Culture wanes. Language lingers. And people scatter. Nonetheless, a few survivors can run for a time on the fumes of past glory. So there can be gradations of obliteration. We must examine carefully whether a Thebes or Carthage was really destroyed as recorded – and indeed exactly what is meant in our sources by verbs like “destroyed,” “razed,” and “leveled.”

From the fall of Troy to the atomization of much of Hiroshima, the destruction of cities and occasionally their entire civilizations, as mentioned, is unusual but also not yet a thing of our savage past. A small number of these catastrophes still reverberate through the centuries. Sometimes these obliterations changed the lives of quite different peoples, well beyond the dead and enslaved. Millions far from ground zero grasped almost immediately that the ripples of destruction would ultimately alter their lives as well. Subsequent generations in retrospect realized these annihilations had marked the abrupt end of an age and a transition to something quite different.

Whether the significance of an entire political system lost, a culture vanished, or a distinct people erased became obvious in real time or only later, there nonetheless remain certain similarities – and thus lessons – in these historic wartime disappearances of whole societies.

The size and wealth of the targeted population made a difference. The ancient world rued the Athenian extinction of the tiny island of Melos and its culture in 415 BC. But the classical Greeks did not equate a world without the Melians with the loss of Hellenism, at least in the manner of the later razing of a much larger and more influential Thebes or Corinth. The language, literature, art, and science of the vanished, and their ability to transcend their own borders also mattered. The world of Asia Minor and the Mediterranean changed after the end of Byzantine Constantinople far more than following the obliteration of the barbarian Vandals in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy.

Four examples – the leveling of Thebes by Alexander the Great, the erasure of Carthage by Scipio Aemilianus, Sultan Mehmet II’s conquest and transformation of Constantinople, and the obliteration of Tenochtitlan by Hernan Cortes – all marked the end of cultures and civilizations. They were seen so by contemporaries and later generations alike.

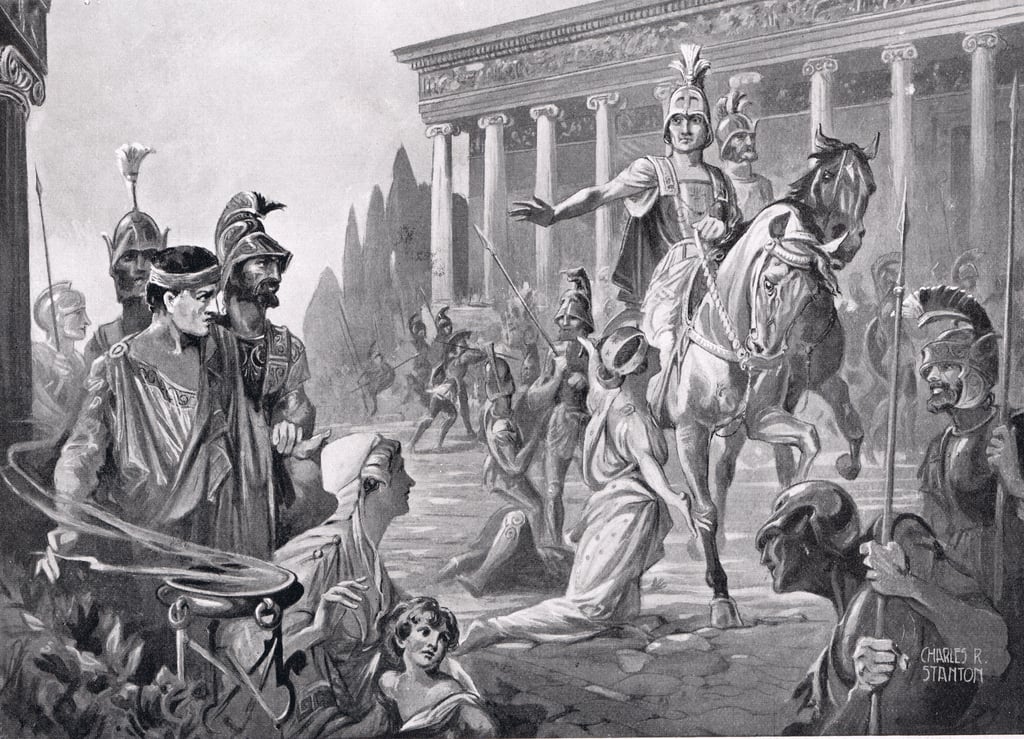

Thebes and the end of Greek city-states

Alexander brought a close to the Classical Greece of hundreds of independent city-states with the extinction of Thebes and its inhabitants. The implosion of the independent citystate inaugurated a very different subsequent Hellenistic era of imperial kingdoms and values.

The city of Thebes was renowned in history and myth. In 335 BC, the Thebans not only revolted against the Macedonian occupation of Greece, but defiantly dared Alexander the Great to take the legendary city. He did just that, after a brief but savage one-day battle. He then quite unexpectedly enlisted other conquered Greek city-states to ratify his decision to raze the city, kill off most of the adult males, sell the surviving captives into slavery, and allow neighbors to appropriate Theban territory. Thereby Alexander ended for good the ancient citadel of Cadmus, mythical founder of the hallowed city.

More than just Thebes itself was destroyed. The annihilation of the Thebans marked the iconic finale of the entire era of independent city-states that the rebellious Thebans had sought to save. After the obliteration of Thebes, one empire or kingdom succeeded another on Greek soil – first Alexander and his Hellenistic Diadochoi (“Successors”), then Rome and Byzantium, then the Ottomans, and finally the independent Greek monarchy. Yet the creative polis civilization of the golden age, not just of Thebes but of Athens and the rest of Greece as well, vanished after Alexander.

Rome eradicates Carthage

Some 189 years after the end of Thebes, the lethal rivalry between Rome and Carthage culminated in the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC at the end of the Third Punic War when the Carthaginians likewise disappeared as a people. Punic civilization itself vanished with its capital city. Like the Thebans, they perished by siege, after their once distant frontiers had collapsed to just the city’s suburbs. The destruction of Carthage saw the disappearance of the last major obstacle to a Roman Western Mediterranean. Its obliteration brought North Africa into the West, and accelerated Rome’s transformation from a republic to an imperial power. The once Mediterranean-wide Carthaginian language, literature, and people receded to only distant memories in the Greco-Roman centuries that followed.

Carthage in its three Punic Wars had fought Rome too long and become too vulnerable. Its existence became perceived as not so much an existential danger as a constant irritant to Rome. Its fate was mostly irrelevant to others. And Rome sought an opening to extinguish an economic rival and appropriate its wealth. The fall of Carthage, and the almost contemporary destruction of Corinth and creation of Roman provinces in Greece, traditionally were seen by historians as both the emblematic cessations of the Hellenistic kingdoms and the beginning of the Roman Mediterranean world.

The Ottomans obliterate Constantinople

The most infamous of wartime extinctions was the destruction of Byzantine Constantinople on May 29, 1453, “Black Tuesday.” The fall of Constantinople confirmed the decline of the Mediterranean world as the nexus of European commerce. The loss of the city ended the formal European presence in Asia, even as it helped to inaugurate in the opposite direction a new Atlantic world dominated by Portugal, Spain, France, and later Holland and England.

While the Greek language and Orthodox Christian religion survived scattered in southern Europe and in the outlands of Asia after the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the millennium-long reality of an Eastern, Greek-speaking Roman Empire and attendant cult in Asia Minor disappeared – despite Russia’s later claims of reestablishing a third Christian Rome. Constantinople had survived and more or less recovered from the brutal sack by Western knights of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

But it would not rebound from the far more ambitious agenda of Sultan Mehmet II, who would finish off Byzantine civilization, and appropriate and transform its renowned capital. He announced that he was now the only and rightful heir to the Roman Empire. But even the sultan did not foresee that his own choices would spur Western Europe to conquer the world by sea to avoid Ottoman Kostantiniyye’s increasing control and disruption of EastWest Mediterranean trade.

The Ottomans harbored a hatred of Christianity. They had assumed rightly that Constantinople was old and weak and mostly long abandoned by Western Christendom. After the end, Hagia Sophia, the largest Christian cathedral in the West for seven hundred years, became the greatest mosque of the Islamic world. There were never again to be Byzantines, the Greek city of Constantinople, or even the idea of any cohesive Christian, Greek-speaking Hellenic culture in Asia. The Greek shell of the sacked city remained, given its strategically invaluable site at the Bosporus. But now it was to be absorbed as the new dynamic capital Kostantiniyye of the ascendant Ottoman Empire, and in modern times renamed Istanbul.

From a global perspective, the fall of Constantinople marked the end of the Eastern Mediterranean-centered world, the transference of Hellenic power and influence to Renaissance Europe, and soon, the beginning of the Atlantic era. In 1444, a near decade before the city fell, Portuguese explorers, trying to find a maritime route around Ottoman control of the Mediterranean and the land routes to Asia, had already reached the westernmost point of Africa. Well south of the Sahara, they were beginning to circumvent Muslim control of trade with the African Gold Coast. By 1488, they had reached the Cape of Good Hope, ensuring Europeans soon had direct access to trade with Asia. In 1492, a mere thirty-nine years after the fall of Constantinople, Europeans discovered the New World.

Like “vandal,” “Byzantine” as a living concept survives today only as an adjective. It is used inexactly and unfairly to convey the supposed inefficiency and intrigue of fossilized, bloated bureaucracies. Otherwise, the Byzantines receded into the collective Greek memory. The idea of a living Byzantium reemerged only once, as an ephemeral fantasy. After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1918, the Hellenic dream of the ?????? ???? (Megali Idea or “Great Idea”) gained increased impetus, but then soon afterward died for good. This new incarnation of the Megali Idea had envisioned a twentieth-century Panhellenic Aegean, once more united by Greek-speakers in Asia Minor, the Greek mainland, the Islands, and the northern Egyptian coast. It was crushed by Turkish nationalist Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s army at the final conflagration in Smyrna (1922), and finished off by the nascent state of Turkey.

Cortes destroys the Aztec Empire

The savage work of Hernan Cortes in the destruction of the Aztec Empire normalized the crushing of independent native states in the Americas while birthing a new Spanish-speaking civilization there, one neither altogether indigenous nor Spanish. After Cortes’s siege of Tenochtitlan in 1521 and annihilation of its empire, there was no longer a concept of an Aztec people or a majestic indigenous capital in its Venice-like island city of canals.

Indeed, there was little left except subsequent mythologies of a lost Aztlan homeland in the US Southwest, and enslaved laborers constructing the new Spanish capital of Mexico City, deliberately put down atop the site of the old. Like Carthage and Constantinople, Tenochtitlan had been the nerve center of a brittle empire, a single great city organizing thousands of square miles on its periphery.

Although they had become familiar with Aztec civilization over the prior two years, the Spanish almost immediately sought to obliterate its religion, race, and culture. In their view, they had more than enough reasons to destroy the Aztec Empire rather than just defeat the Mexica (the indigenous word for “Aztec”). As with Thebes, the destruction of Tenochtitlan and the Mexica empire did not just erase one state. The demise of the city marked the end of Central American altepetl (“city-state”) civilization as a whole. When combined with the later Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, indirectly inspired by Cortes, the city’s death marked the collapse of the age of independent New World civilizations.

“It cannot happen here”

There is a tragic but predictable scheme to all these geographically and ethnically different examples. They offer timely warnings for us and our own future. Even as humanity supposedly becomes more uniform and interconnected, so too our world grows increasingly vulnerable and dangerous, as the margins of human error and misapprehension in conflict shrink – from Ukraine to Taiwan to the Middle East.

We should remember that the world wars of the last century likely took more human life than all armed conflicts combined since the dawn of Western civilization twenty-five hundred years prior. And they did so with offensive weapons already obsolete, and all too familiar destructive agendas that persist today, unchanged since antiquity.

As for the targets of aggression, the old mentalities and delusions that doomed the Thebans, the Carthaginians, the Byzantines, and the Aztecs are also still very much with us, especially the last thoughts of the slaughtered: “It cannot happen here.”

Excerpted from The End of Everything: How Wars Descend Into Annihilation by Victor Davis Hanson. Copyright © 2024. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.